October 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide

Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Guide to the educational resources available on the GHS website Theme driven guide to: Online exhibits Biographical Materials Primary sources Classroom activities Today in Georgia History Episodes New Georgia Encyclopedia Articles Archival Collections Historical Markers Updated: July 2014 Georgia Historical Society Educator Web Guide Table of Contents Pre-Colonial Native American Cultures 1 Early European Exploration 2-3 Colonial Establishing the Colony 3-4 Trustee Georgia 5-6 Royal Georgia 7-8 Revolutionary Georgia and the American Revolution 8-10 Early Republic 10-12 Expansion and Conflict in Georgia Creek and Cherokee Removal 12-13 Technology, Agriculture, & Expansion of Slavery 14-15 Civil War, Reconstruction, and the New South Secession 15-16 Civil War 17-19 Reconstruction 19-21 New South 21-23 Rise of Modern Georgia Great Depression and the New Deal 23-24 Culture, Society, and Politics 25-26 Global Conflict World War One 26-27 World War Two 27-28 Modern Georgia Modern Civil Rights Movement 28-30 Post-World War Two Georgia 31-32 Georgia Since 1970 33-34 Pre-Colonial Chapter by Chapter Primary Sources Chapter 2 The First Peoples of Georgia Pages from the rare book Etowah Papers: Exploration of the Etowah site in Georgia. Includes images of the site and artifacts found at the site. Native American Cultures Opening America’s Archives Primary Sources Set 1 (Early Georgia) SS8H1— The development of Native American cultures and the impact of European exploration and settlement on the Native American cultures in Georgia. Illustration based on French descriptions of Florida Na- tive Americans. -

Bee Round 2 Bee Round 2 Regulation Questions

NHBB C-Set Bee 2017-2018 Bee Round 2 Bee Round 2 Regulation Questions (1) This city's CRASH anti-gang unit was the subject of the Rampart police corruption scandal in the late-1990s. Sixteen people died in this city's Northridge Meadows Apartments on Reseda Boulevard in a 1994 earthquake. Rebel Without a Cause was set in this city, filming at its Griffith Observatory. Sid Grauman built a \Chinese Theater" and an \Egyptian Theater" in this city. Brentwood and Bel-Air are neighborhoods of, for the point, what most populous city of California? ANSWER: Los Angeles (2) This man led a squadron of ships past a blockade of Presque Isle Bay to sail to Put-in-Bay. In one battle, this man transferred his command from the Lawrence to the Niagara when his first flagship was destroyed. After defeating a British fleet in an engagement during the War of 1812, this man declared \We have met the enemy and they are ours." For the point, name this victor of the Battle of Lake Erie. ANSWER: Oliver Hazard Perry (prompt on Perry) (3) In 1939, invading Japanese troops devised the never-enacted Otani plan for this project. John L. Savage surveyed for this project, whose construction drove the baiji dolphin to extinction and displaced 1.3 million people near Chongqing. The Itaipu Dam was surpassed in power output after the completion of, for the point, what massive hydroelectric dam on the Yangtze River, the largest in the world? ANSWER: Three Gorges Dam (4) The provisions of this document were reaffirmed by the Resolutions of Edward Coke. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

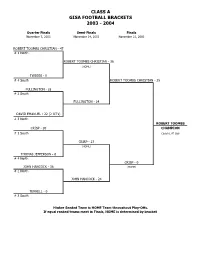

Class a Gisa Football Brackets 2003 - 2004

CLASS A GISA FOOTBALL BRACKETS 2003 - 2004 Quarter Finals Semi-Finals Finals November 7, 2003 November 14, 2003 November 21, 2003 ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 47 # 1 North ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 36 (HOME) TWIGGS - 0 # 4 South ROBERT TOOMBS CHRISTIAN - 35 FULLINGTON - 28 # 2 South FULLINGTON - 24 DAVID EMANUEL - 22 (2 OT's) # 3 North ROBERT TOOMBS CRISP - 20 CHAMPION # 1 South Coach L.M. Guy CRISP - 27 (HOME) THOMAS JEFFERSON - 6 # 4 North CRISP - 0 JOHN HANCOCK - 38 (HOME) # 2 North JOHN HANCOCK - 24 TERRELL - 0 # 3 South Higher Seeded Team is HOME Team throughout Play-Offs. If equal ranked teams meet in Finals, HOME is determined by bracket. 2003 GISA STATE FOOTBALL BRACKETS Friday, Nov. 7 AA BRIARWOOD - 21 Friday, Nov. 14 R1 # 1 Home is team with highest rank; when teams are (1) BRIARWOOD - 15 equally ranked, Home is as shown on brackets. (HOME) WESTWOOD - 0 Friday, Nov. 21 R3 # 4 (9) BRIARWOOD - 14 MONROE - 0 R4 # 2 (2) BULLOCH - 0 BULLOCH - 35 R2 # 3 Friday, Nov. 28 TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 47 R2 # 1 SOUTHWEST GA - 25 (3) TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 17 (13) (Home) (HOME) GATEWOOD - 6 R4 # 4 (10) TRINITY CHRISTIAN - 14 (HOME) BROOKWOOD - 6 R3 # 2 (4) BROOKWOOD - 14 EDMUND BURKE - 14 (15) BRENTWOOD R1 # 3 AA CHAMPS Coach Bert Brown SOUTHWEST GEORGIA - 51 R3 # 1 BRENTWOOD - 52 (5) SOUTHWEST GA - 44 (14) (HOME) CURTIS BAPTIST - 14 R1 # 4 (11) SOUTHWEST GA - 27 TIFTAREA - 42 (HOME) R2 # 2 (6) TIFTAREA - 14 PIEDMONT - 16 R4 # 3 FLINT RIVER - 27 R4 # 1 (7) FLINT RIVER - 21 (HOME) MEMORIAL DAY - 6 R2 # 4 (12) BRENTWOOD - 25 BRENTWOOD - 42 R1 # 2 (8) BRENTWOOD - 46 VALWOOD - 30 R3 # 3 2003 GISA STATE FOOTBALL BRACKETS Friday, Nov. -

Andrew Jackson Collection, 1788-1942

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 ANDREW JACKSON COLLECTION, 1788-1942 Accession numbers: 3, 37, 38, 41, 297, 574, 582, 624, 640, 646, 691, 692, 845, 861, 968, 971, 995, 1103, 1125, 1126, 1128, 1170 1243, 1301, 1392, 69-160, and 78-048 Processed by Harriet C. Owsley and Linda J. Drake Date completed: June 1, 1959 Revised: 1964 Microfilm Accession Number: Mf. 809 Location: VI-A-4-6 The collected papers of and materials about Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), Judge Advocate of Davidson County, Tennessee, Militia Regiment, 1791; member of Congress, 1796-1798, 1823- 1824; Major General, United States Army, 1814; Governor of Florida Territory, 1821; and President of the United States, 1828-1836, were collected by Mr. And Mrs. John Trotwood Moore on behalf of the Tennessee State Library and Archives during their respective terms as State Librarian and Archivist. The documents were acquired from various sources. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 6.0 Approximate number of items: 1.500 Single photocopies of unpublished writings may be made for purposes of scholarly research. Microfilm Container List Reel 1: Box 1 to Box 3, Folder 13 Reel 2: Box 3, Folder 13 to Box 6, Folder 2 Reel 3: Box 6, Folder 3 to Box 9 On Reel 3 of the microfilm, targets labeled box 5 should be labeled Box 6. SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE The Andrew Jackson Papers, approximately 1,500 items (originals, photostats, and Xerox copies) dating from 1788 to 1942, are composed of correspondence: legal documents; clippings; documents about the Dickinson duel; articles about Andrew Jackson; biographical data concerning Andrew Jackson; biographical data concerning Ralph Earl (portrait painter); John H. -

Teacher Notes for the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Social Studies

Georgia Studies Teacher Notes for the Georgia Standards of Excellence in Social Studies The Teacher Notes were developed to help teachers understand the depth and breadth of the standards. In some cases, information provided in this document goes beyond the scope of the standards and can be used for background and enrichment information. Please remember that the goal of social studies is not to have students memorize laundry lists of facts, but rather to help them understand the world around them so they can analyze issues, solve problems, think critically, and become informed citizens. Children’s Literature: A list of book titles aligned to the 6th-12th Grade Social Studies GSE may be found at the Georgia Council for the Social Studies website: https://www.gcss.net/site/page/view/childrens-literature The glossary is a guide for teachers and not an expectation of terms to be memorized by students. In some cases, information provided in this document goes beyond the scope of the standards and can be used for background and enrichment information. Terms in Red are directly related to the standards. Terms in Black are provided as background and enrichment information. TEACHER NOTES GEORGIA STUDIES Historic Understandings SS8H1 Evaluate the impact of European exploration and settlement on American Indians in Georgia. People inhabited Georgia long before its official “founding” on February 12, 1733. The land that became our state was occupied by several different groups for over 12,000 years. The intent of this standard is for students to recognize the long-standing occupation of the region that became Georgia by American Indians and the ways in which their culture was impacted as the Europeans sought control of the region. -

1906 Catalogue.Pdf (7.007Mb)

ERRATA. P. 8-For 1901 Samuel B. Thompson, read 1001 Samuel I?. Adams. ' P. 42—Erase Tin-man, William R. P. 52—diaries H. Smith was a member of the Class of 1818, not 1847. : P. 96-Erase star (*) before W. W. Dearing ; P. 113 Erase Cozart, S. W. ' P. 145—Erase Daniel, John. ' j P. 1GO-After Gerdine, Lynn V., read Kirkwood for Kirkville. I P. 171—After Akerman, Alfred, read Athens, (Ja., for New Flaven. ; P. 173—After Pitner, Walter 0., read m. India Colbort, and erase same ' after Pitner, Guy R., on p. 182. • P. 182-Add Potts, Paul, Atlanta, Ga. , ! CATALOGUE TRUSTEES, OFFICERS, ALUMNI AND MATRICULATES UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, AT ATHENS, GEORGIA, FROM 1785 TO 19O<». ATHENS, OA. : THF, E. D. STONK PRESS, 190G. NOTICE. In a catalogue of the alumni, with the meagre information at hand, many errors must necessarily occur. While the utmost efforts have been made to secure accuracy, the Secretary is assurer) that he has, owing to the impossibility of communicating with many of the Alumni, fallen far short of attaining his end. A copy of this catalogue will be sent to all whose addresses are known, and they and their friends are most earnestly requested to furnish information about any Alumnus which may be suitable for publication. Corrections of any errors, by any person whomsoever, are re spectfully invited. Communications may be addressed to A. L. HULL, Secretary Board of Trustees, Athens, Ga. ABBREVIATIONS. A. B., Bachelor of Arts. B. S., Bachelor of Science. B. Ph., Bachelor of Philosophy. B. A., Bachelor of Agriculture. -

Simmons Brothers

PAGE TE� BULLOCH TIMES AND STATESBORO NEWS THURSDAY. OCTOBER 12. 1922 - 75 SUTLER--SMITH. WOMAN'S CLUB CONCERT. You Can Get at The (The home of Mrs. W. T. Smith Wll8 The eoneert given by the Trice Things 16 East Main Street. "On the Square" the scene ot a pretty wedding Wed Carlton Go�pany and onder the nesday evening. October Lltb, 1922, auapiees of the Woman's Club at the when her aoditorium on .. daughter. Nellie, became last Friday evening Golden the bride of to Raad Tea Room Sutler. proved be a Philip qoite BUcceSS from the 1·,1"r8. A. W. of both Brannen Co. Quattlebaum played standpoint entertainment and Hardware Sandwiches of all kinds '.,. I Lohengrin's wedding march. as the finances. bride The Winchester Store Salads as you like them descended the stairs. An appreci:ative andience greeted The WB8 number an Ice Cream and ceremony performed by every the program with Headquarte1'. for Sundaes, and Cold Drinks Rev. T. M. Christian of the States applause whieb the IMES performers grae (STATESBORO boro Methodist church. NEWS-STATESBORO 75c and The marriage iously acknowledged with pleaBing en Winchester Guns. Shells. Tools. Etc. lullocn EAGLE) Regular Meals-50c, $1.00 'I'imes, E;t:abi,shod . was B· simple &!fair, no invitations be cores. St.atesboro News, Established1�92}1901 Consolidated January 17. 1917. The Oysters any style. ing issued. TI'i",,-Cariton was Blateshor� Eagle. Established Company 1917--Consolfdated Decemb�l"9. 1920. STATESBORO, CA., THURSDAY. OCTOBER 19, 1922. after the a ably assisted the Get Our Prices Before If Immediately ceremony by fonowing repre VOL. -

Answer Key SS8H1 – SS8H12

Georgia Milestones Grade 8 Assessments: Social Studies Web Quest Answer Key SS8H1 – SS8H12 Introduction: Answers will vary. TheseAnswer are suggested Key exemplary answers. Students should be encouraged to take their time to read or watch every resource included in the web quest. Simply scanning and grabbing the answers to the questions will not go far to help them digest the material in order to perform well on the EOG assessment. SS8H1 1. They came for wealth and glory. They had heard rumors of wealth equaling the Aztecs. 2. Hernando DeSoto or Hernando de Soto. 3. Exposure to disease and attack from Spanish soldiers was devastating to the Native American populations. 4. The Franciscan monks wanted to establish control over the Native Americans by converting them to Christianity. The monks taught the Native Americans the Spanish language and had them do farming and other labor to support the missions. 5. The Mississippian era was characterized by chiefdoms. This is also the period of mound building. SS8H2 1. The video specifically lists relief for poor, welfare, and defense. The colony was established to give the “worthy poor” a fresh start in the new colony and provide a military buffer between Spanish Florida and the English colonies. 2. James Edward Oglethorpe was the founder of the Georgia colony. He gave the inspiration for the Georgia colony as a haven for poor British citizens. He helped get a charter approved from King George II. He sailed with the first settlers and acted as the unofficial governor of the colony for 10 years. He led in the defense against the Spanish and negotiated with the Yamacraw Indians. -

18 Lc 117 0041 H. R

18 LC 117 0041 House Resolution 914 By: Representatives Williamson of the 115th and Kirby of the 114th A RESOLUTION 1 Recognizing and proclaiming Walton County Bicentennial Celebration Day; and for other 2 purposes. 3 WHEREAS, Walton County was created on December 15, 1818, by the Lottery Act of 1818 4 and is named in honor of George Walton, who was a signer of the United States Declaration 5 of Independence and served as Governor of Georgia and United States senator; and 6 WHEREAS, Walton County, located 45 miles east of Atlanta in Georgia's beautiful 7 Piedmont region, is the state's 46th county; and 8 WHEREAS, eight governors were born or resided within the borders of Walton County, 9 including Texas Governor Richard B. Hubbard and Georgia Governors Wilson Lumpkin, 10 Howell Cobb, Alfred H. Colquitt, James S. Boynton, Clifford Walker, Richard B. Russell, 11 Jr., and Henry McDaniel, who as Georgia's 37th governor from 1883 to 1886, signed the bill 12 into law that established Georgia Tech as a technical university on October 13, 1885; and 13 WHEREAS, Good Hope in Walton County was the home of Miss Moina Belle Michael, the 14 "Poppy Lady," who established the poppy as a memorial to veterans; and 15 WHEREAS, Walton County comprises the cities of Monroe, the county seat, which was 16 incorporated in 1821; Between, incorporated in 1908; Good Hope, incorporated in 1905; 17 Jersey, incorporated in 1905; Loganville, incorporated in 1914; Social Circle, incorporated 18 in 1869; and Walnut Grove, incorporated in 1905; as well as the unincorporated communities 19 of Bold Springs, Campton, Gratis, Mt. -

George Washington Campbell Correspondence, 1793-1833

State of Tennessee Department of State Tennessee State Library and Archives 403 Seventh Avenue North Nashville, Tennessee 37243-0312 GEORGE WASHINGTON CAMPBELL (1769-1848) CORRESPONDENCE 1793-1833 Processed by: Harriet Chappell Owsley Archival Technical Services Accession Numbers: 1246; 1256 Date Completed: October 28, 1964 Location: IV-F-4 INTRODUCTION This collection of papers (Photostats primarily) of George Washington Campbell (1769-1833), lawyer, Tennessee member of Congress, 1803-1809, U.S. Senator from Tennessee, 1811-1818, Secretary of the Treasury (briefly), Minister to Russia, 1818- 1820, and, U.S. Claims Commissioner, 1831, were given to the State by his descendants. Five original letters written by nephews of G.W. Campbell were also deposited by descendants. The materials in this finding aid measures .42 linear feet. There are no restrictions on the materials. Single photocopies of unpublished writings in the George Washington Campbell Correspondence may be made for purposes of scholarly research. SCOPE AND CONTENT This collection is composed of correspondence (Photostats and five original letters) of George Washington Campbell for the dates 1793-1833. The bulk of the material falls in the period 1813-1822 when Campbell was United States Senator, Secretary of the Treasury, and Minister to Russia. The letters are especially concerned with national and diplomatic problems involving the purchase of East Florida from Spain, diplomatic relations with Great Britain during the period of Jackson’s execution of Ambrister and Arbuthnot, conditions in France after the Revolution, treaties with European Countries, and subjects of national concern. His correspondents included four presidents – Andrew Jackson, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, and James Madison. -

2007 GISA Baseball

2007 GISA STATE BASEBALL TOURNAMENT - CLASS A Best 2 out of 3 for ALL Series Game 1 & 2 - April 24 "IF" Game - April 25 Game 1 & 2 - April 30 "IF" Game - May 1 Game 1 - May 4 Game 2 & "IF" - May 5 Game 1 - May 11 Game 2 & "IF" - May 12 Nathanael Greene R1 # 1 7-4 / 3-0 (1) Nathanael Greene (Home) Crisp 11-1 / 14-1 R3 # 4 (9) Nathanael Greene LaGrange (Home) R4 # 2 G2 20-10 / 21-1 (2) LaGrange G1 10-4 Robert Toombs R2 # 3 Thomas Jefferson R2 # 1 Fullington 15-0 / 18-0 (3) Thomas Jefferson (13) (Home) (Home) Oak Mountain G1 4-3 G3 16-6 G1 - Fri 4pm R4 # 4 (10) Thomas Jefferson G2 Sat 1pm (Home) Terrell 13-3 / 4-0 R3 # 2 G2 9-1 (15) Fullington Academy (4) Terrell Class A Champs Curtis Baptist R1 # 3 Fullington R3 # 1 (14) Thomas Jefferson 15-0 / 10-0 (5) Fullington (Home) Monsignor Donovan 4-1 / 5-1 R1 # 4 (11) Fullington David Emanuel R2 # 2 6-1 / 15-0 (6) David Emanuel Heirway Christian R4 # 3 Flint River R4 # 1 G2 14-1 / 14-7 (7) Flint River G1 5-1 (Home) Citizens Christian 4-0 / 13-8 R2 # 4 (12) Flint River John Hancock R1 # 2 (8) John Hancock Home is team with highest rank; when teams are Georgia Christian equally ranked, Home is as shown on brackets. R3 # 3 2007 GISA STATE BASEBALL TOURNAMENT - CLASS AA Best 2 out of 3 for ALL Series Game 1 & 2 - April 24 "IF" Game - April 25 Game 1 & 2 - April 30 "IF" Game - May 1 Game 1 - May 4 Game 2 & "IF" - May 5 Game 1 - May 11 Game 2 & "IF" - May 12 Windsor R1 # 1 10-0 / 9-3 (1) Windsor (Home) Randolph Southern 11-1 / 12-7 R3 # 4 (9) Windsor Griffin Christian (Home) R4 # 2 Fri - 4pm G2 12-3