Wicked Words, Virtuous Voices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

Early Modern Low Countries 1 (2017) 1, pp. 30-50 - eISSN: 2543-1587 30 ‘Before she ends up in a brothel’ Public Femininity and the First Actresses in England and the Low Countries Martine van Elk Martine van Elk is a Professor of English at California State University, Long Beach. Her research interests include early modern women, Shakespeare, and vagrancy. She is the author of numerous essays on these subjects, which have appeared in essay collections and in journals like Shakespeare Quarterly, Studies in English Literature, and Early Modern Women. Her book Early Modern Women’s Writing: Domesticity, Privacy, and the Public Sphere in England and the Low Countries has been pub- lished by Palgrave Macmillan (2017). Abstract This essay explores the first appearance of actresses on the public stage in England and the Dutch Republic. It considers the cultural climate, the theaters, and the plays selected for these early performances, particularly from the perspective of public femininity. In both countries antitheatricalists denounced female acting as a form of prostitution and evidence of inner corruption. In England, theaters were commercial institutions with intimate spaces that capitalized on the staging of privacy as theatrical. By contrast, the Schouwburg, the only public playhouse in Amsterdam, was an institu- tion with a more civic character, in which the actress could be treated as unequivocally a public figure. I explain these differences in the light of changing conceptions of public and private and suggest that the treatment of the actress shows a stronger pub- lic-private division in the Dutch Republic than in England. -

THE POWER of BEAUTY in RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr

THE POWER OF BEAUTY IN RESTORATION ENGLAND Dr. Laurence Shafe [email protected] THE WINDSOR BEAUTIES www.shafe.uk • It is 1660, the English Civil War is over and the experiment with the Commonwealth has left the country disorientated. When Charles II was invited back to England as King he brought new French styles and sexual conduct with him. In particular, he introduced the French idea of the publically accepted mistress. Beautiful women who could catch the King’s eye and become his mistress found that this brought great wealth, titles and power. Some historians think their power has been exaggerated but everyone agrees they could influence appointments at Court and at least proposition the King for political change. • The new freedoms introduced by the Reformation Court spread through society. Women could appear on stage for the first time, write books and Margaret Cavendish was the first British scientist. However, it was a totally male dominated society and so these heroic women had to fight against established norms and laws. Notes • The Restoration followed a turbulent twenty years that included three English Civil Wars (1642-46, 1648-9 and 1649-51), the execution of Charles I in 1649, the Commonwealth of England (1649-53) and the Protectorate (1653-59) under Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) personal rule. • Following the Restoration of the Stuarts, a small number of court mistresses and beauties are renowned for their influence over Charles II and his courtiers. They were immortalised by Sir Peter Lely as the ‘Windsor Beauties’. Today, I will talk about Charles II and his mistresses, Peter Lely and those portraits as well as another set of portraits known as the ‘Hampton Court Beauties’ which were painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723) during the reign of William III and Mary II. -

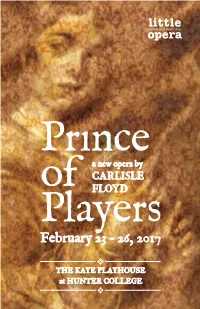

View the Program!

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

“Revenge in Shakespeare's Plays”

“REVENGE IN SHAKESPEARE’S PLAYS” “OTHELLO” – LECTURE/CLASS WRITTEN: 1603-1604…. although some critics place the date somewhat earlier in 1601- 1602 mainly on the basis of some “echoes” of the play in the 1603 “bad” quarto of “Hamlet”. AGE: 39-40 Years Old (B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: Four years after “Hamlet”; first in the consecutive series of tragedies followed by “King Lear”, “Macbeth” then “Antony and Cleopatra”. GENRE: “The Great Tragedies” SOURCES: An Italian tale in the collection “Gli Hecatommithi” (1565) of Giovanni Battista Giraldi (writing under the name Cinthio) from which Shakespeare also drew for the plot of “Measure for Measure”. John Pory’s 1600 translation of John Leo’s “A Geographical History of Africa”; Philemon Holland’s 1601 translation of Pliny’s “History of the World”; and Lewis Lewkenor’s 1599 “The Commonwealth and Government of Venice” mainly translated from a Latin text by Cardinal Contarini. STRUCTURE: “More a domestic tragedy than ‘Hamlet’, ‘Lear’ or ‘Macbeth’ concentrating on the destruction of Othello’s marriage and his murder of his wife rather than on affairs of state and the deaths of kings”. SUCCESS: The tragedy met with high success both at its initial Globe staging and well beyond mainly because of its exotic setting (Venice then Cypress), the “foregrounding of issues of race, gender and sexuality”, and the powerhouse performance of Richard Burbage, the most famous actor in Shakespeare’s company. HIGHLIGHT: Performed at the Banqueting House at Whitehall before King James I on 1 November 1604. AFTER: The play has been performed steadily since 1604; for a production in 1660 the actress Margaret Hughes as Desdemona “could have been the first professional actress on the English stage”. -

'Prince of Players' Score Soars, While Libretto Is a Letdown

LIFESTYLE 'Prince of Players' score soars, while libretto is a letdown By Joseph Campana | March 7, 2016 0 Photo: Marie D. De Jesus, Staff Ben Edquist, plays the lead role Edward Kynaston, a famed actor in England in the 1700s whose career is abruptly stopped when the king issues a decree prohibiting men from playing women in stage roles. Armenian soprano Mane Galoyan will sing Margaret Hughes. The Houston Grand Opera (HGO) will present Prince of Players by distinguished American composer Carlisle Floyd on March 5, 11, and 13, 2016. ( Marie D. De Jesus / Houston Chronicle ) A night at the opera can leave us speechless or it can send us to our feet shouting "Bravo!" At the close of the Houston Grand Opera world premiere of Carlisle Floyd's "Prince of Players," it was all leaping and shouting. Floyd not only co-founded the Houston Grand Opera Studio, but this great American treasure has now premiered his fifth work for Houston Grand Opera just shy of his 90th birthday. That's plenty to celebrate. But the true achievement of "Prince of Players" is a beautifully realized production of an ambitious commission with an electrifying score stirringly conducted by Patrick Summers. From its opening moments, "Prince of Players" resounds with tonal unease, surreptitious woodwinds and warning strings. And in mere seconds, Floyd conveys that, in spite of some fun and flirtation to come, we are in the presence of a sea-change, and no one will remain unscathed. The marvel of Floyd is his attention to moments great and small. Some of the most compelling passages come seemingly between scenes or in the absence of voice - as an actor silently practices his gestures or as the court eerily processes before their king. -

10-Fr-736-Booklet-W.O. Crops

CARLISLE PRINCE OF FLOYD PLAYERS an oPera in two acts Phares royal Dobson shelton Kelley riDeout harms eDDy fr esh ! MILWAUKEE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA WILLIAM BOGGS , CONDUCTOR FROM THE COMPOSER it is with great pleasure and pride that i congratulate the Florentine opera and soundmirror on this beautiful recording. it is the culmination of all the hard work and love that many people poured into making this opera a success. From its very beginning, Prince of Players has been a joy for me. back in 2011, i was flipping through tV channels and stopped on an interesting movie called staGe beauty, based on Jeffery hatcher’s play “the compleat Female stage beauty” and directed by sir richard eyre. the operatic potential struck me immediately. opera deals with crisis, and this was an enormous crisis in a young man’s life. i felt there was something combustible in the story, and that’s the basis of a good libretto. i always seek great emotional content for my operas and i thought this story had that. it is emotion that i am setting to music. if it lacks emotion, i know it immediately when i try to set it to music: nothing comes. From the story comes emotion, from the emotion comes the music. Fortunately for me, the story flowed easily, and drawing from the time-honored dramatic cycle of comfort, disaster, rebirth, i completed the libretto in less than two weeks. in 2013, the houston Grand opera commissioned Prince of Players as chamber opera, to be performed by its hGo studio singers, and staged by the young british director, michael Gieleta. -

Harlem Shakespeare Fes- Tival Welcome to Everyone Visiting Taliesin West to Support

SHAKESPEARE HARLEM F E S T I V A L Taliesin West, Scottsdale, AZ | April 19 – 28, 2019 19 APRIL 2019 We would like to extend a warm Harlem Shakespeare Fes- tival welcome to everyone visiting Taliesin West to support Southwest Shakespeare Company’s much anticipated presentation of HARLEM SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL'S ALL-FEMALE OTHELLO, directed by Vanessa Morosco with live cello orchestrations by Chinese cellist Wei Guo. Harlem Shakespeare Festival is dedicated to supporting women, youth and especially classically trained artists of color. We exist primarily to help classical actors of color to realize their full potential. Central to these efforts is the staging of traditional classic works that showcase multi- racial casts. It is our intention to expose the public to the A NOTE FROM THE PRODUCERS THE NOTE FROM A works of these artists as a means of opening up a dialogue of cultural diversity, understanding and unity in the arts. As is our custom we have pulled together a team of ex- traordinary women to help create this wonderful collabora- tion. Four of the cast members are from New York and four are from Arizona. Our director and costume designer are from Harlem Shakespeare and our fight director and stage manager are from Southwest Shakespeare; making this a true collaboration indeed! My producing partner, Voza Rivers, and I are truly grateful to Mary Way and the Southwest Shakespeare Team and Board for partnering with us on this project. And I am in- deed honored to be chosen as Southwest Shake’s Artist-in- Residence for their landmark 25th Anniversary Season. -

Who Are the Women on the Timeline?

Writing Women Into History – Who are the women on the timeline? Boudica b AD 33 Also known as or Boudicca, Boadicea or Boudicea, was a queen of a British Celtic tribe, the Iceni. She had been married to Prasutagus, ruler of the Iceni, but when he died the Romans decided to rule the tribe directly. As a result of their treatment of Boudica and her daughters, she led an uprising against them. Boudicca's warriors successfully defeated the Roman Ninth Legion and destroyed Colchester, London and Verulamium (St Albans). She died shortly after she was finally defeated and is said to have poisoned herself. Saint Bertha of Kent b approx. 565 Bertha was married to King Æthelbhert and her influence on her husband was said to have led to him giving St Augustine the freedom to preach and reside in Canterbury. She was canonized as a saint for helping to re-introduction of Christianity to England Hilda of Whitby or Hild of Whitby b approx. 614 St Hilda is a Christian saint who was a nun and the founding abbess of the monastery at Whitby. The abbey was a double monastery, home to both monks and nuns, which was not uncommon at the time. Hilda’s strength and wisdom were well known and the monastery was known for its observance of peace, charity, justice and piety. It was chosen as the venue for the Synod of Whitby, where a dispute over the date of Easter was decided. A legend tells that Hilda turned a plague of snakes to stone, explaining the ammonite fossils found in Whitby. -

Staging the Actress

STAGING THE ACTRESS: DRAMATIC CHARACTER AND THE PERFORMACE OF FEMALE IDENTITY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Melissa Lee Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Lesley Ferris, Advisor Beth Kattelman Jennifer Schlueter Copyright by Melissa Lee 2014 ABSTRACT Since women first took to the professional stage, actresses have been objects of admiration and condemnation as well as desire and suspicion. Historically marginalized figures, actresses challenged notions of acceptable female behavior by, among other (more scandalous) things, earning their own income, cultivating celebrity, and being sexually autonomous. Performance entailed an economic transaction of money for services provided, inviting the sexual double meanings of female “entertainer” and “working” woman. Branding the actress a whore not only signaled her (perceived) sexual availability, but also that she was an unruly woman who lived beyond the pale. The history of the actress in the West is also complicated by the tradition of the all-male stage, which long prevented women from participating in their own dramatic representations and devalued their claim to artistry once they did. Theatrical representations of actresses necessarily engage with cultural perceptions of actresses, which historically have been paradoxical at best. In this dissertation I identify a sub-genre of drama that I call actress-plays, and using this bibliography of over 100 titles I chronicle and analyze the actress as a character type in the English-speaking theatre, arguing that dramatizations of the professional actress not only reflect (and fuel) a cultural fascination with actresses but also enact a counter- narrative to conventional constructions of femininity. -

'The Tempter Or the Tempted, Who Sins Most?': Love and Lust in Measure

‘The tempter or the tempted, who sins most?’: Love and Lust in Measure for Measure and The Law Against Lovers Melissa Merchant On 8 December 1660, following a long history of the prohibition of actresses in England, a feminine presence took to the London stage and altered it.48 The addition of women to the professional stages of England led to changes in the way in which plays were written and presented. This piece explores the relationship between page and stage, looking at it as one that is mutually reflective but non-deterministic. This essay first contextualises the presence of the actress by looking at the sparsely documented contemporary theatre culture in Renaissance and Restoration England, while raising questions about the male narrative. Subsequently this piece uses a comparison of William Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure with Sir William Davenant’s 1662 adaptation, titled The Law Against Lovers, to demonstrate that, at least in terms of adaptations, the feminine presence on the English stage may have resulted in a toning down of the more licentious and sexualised content in Shakespeare’s original. Whilst there appears to have been no specific law in England which forbade women from performing publicly, traditionally the practice was discouraged prior to the Restoration. Indeed, the idea was so unacceptable to the English theatre going public that when, in 1629, a French troupe had attempted to perform with actresses, they were ‘hissed, hooted and pippin- pelted from the stage’.49 Consequently, English drama was coloured by this custom of male exclusivity, and it was in this world that William Shakespeare created each of his plays. -

Teacher Handbook

LADIES AMONG LIONS Teacher handbook Storytree Children’s Theatre presents LADIES AMONG LIONS Written by Laramie Dean Suitable for Grades 4 - 12 Explore the plays of William Shakespeare through the lens of his most famous (and infamous) female characters. The Three Witches take the audience on an unforgettable journey through the words and moments of Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, and Taming of the Shrew and discover the strength and courage of the Bard’s unforgettable women. YOU Have an Important Part to Play How to Play Your Part A play is different than television or a movie. The actors are right in front of you and can see your reactions, feel your attention, and hear your laughter and applause. Watch and listen carefully to understand the story. The story is told by actors and comes to life through your imagination. PAGE 2 storytree children’s theatre Storytree Children’s Theatre Ladies Among Lions Characters P.O. Box 2248 Mt. Pleasant, SC 29465 Witch 1 also plays Katherina, Lady M, and Gertude Phone: (843) 830-8737 Witch 2 also plays Romeo, Peruchio, and Hamlet E-mail: Witch 3 also plays Juliet and Polonious [email protected] About the Playwright Laramie Dean is a Montana native, born and raised on a ranch in northeastern Montana. His move to the “big city” of Missoula in high school allowed him to take drama classes at Teralyn Tanner Hellgate High School, opening up an entire theatrical world of Founder/Executive Director/ possibilities. Laramie earned his BFA in acting at the University of Education Director/ Teaching Artist Montana before moving across the country to work on his PhD in playwriting at Southern Illinois University in Carbondale. -

Compleat Female Stage Beauty

FULLERTON COLLEGE THEATRE ARTS DEPARTMENT PRESENTS... Fullerton College Theatre Arts Department 2014-2015 Season For more information: 714-992-7149 or http://theatre.fullcoll.edu Written by Jeffrey Hatcher An Evening of Comedy Improv Produced by Ron Michaelson Friday, December 12, 2014 8:00pm Bronwyn Dodson Theatre Playwright’s Festival Produced by William Mittler and Amberly Chamberlain Bronwyn Dodson Theatre January 5-23, 2015 (Performance days and times to be determined) Playwright’s Applications due: October 20, 2014 at 5:00pm Auditions: December 8, 2014 at 5pm in the Bronwyn Dodson Theatre The Drowsy Chaperone Music and Lyrics by Lisa Lambert and Greg Morrison Book by Bob Martin and Don McKellar Directed by Chuck Ketter, Choreographed by Tim Espinosa, Vocal Direction by Jo Monteleone Campus Theatre March 12-19, 2015 Vocal auditions: January 20, 2015 at 7:00pm in the Campus Theatre Dance auditions: January 21, 2015 at 7:00pm in the Campus Theatre The Drowsy Chaperone is produced by special arrangement with Music Theatre International High School Theatre Festival Campus Wide March 20 and 21, 2015 Brown Bag Productions, Student Directed Short Plays Produced by Tim Espinosa Room 1310 April 15-18, 2015 Orientation for auditions: January 27, 2015 at 2:00pm in the Bronwyn Dodson Theatre Auditions: January 29, 2015 at 2:00pm in the Bronwyn Dodson Theatre Clybourne Park * by Bruce Norris Directed by Tim Espinosa Bronwyn Dodson Theatre May 7-10, 2015 Orientation for auditions: January 26, 2015 at 2:00pm in the Bronwyn Dodson Theatre Auditions: January 28, 2015 at 2:00pm in the Bronwyn Dodson Theatre *Pending availability Directed by Chuck Ketter Clybourne Park is produced by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service, Inc.