Andrays University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

37007 Dec Tidings.Indd

December 2006 SOUTHERN Spreading Tidings of the Southern Union Adventist Family Evangelism 12 Square Up With God 27 Bass Academy Restored 29 Educating Youth in Record Numbers Vantage Point Jesus, the Light of the World When I was a child–one day long ago and far away–I thought childish, imma- ture thoughts. I was tired of being a dependable, work-your-way-through-school, practice-the-piano teenager. I decided I wanted to be a street fighter. It was a new thought and a foolish thought, given I had zero experience in the street. But, I started paying attention when some of the other big guys would pick a fight and brawl on the ball field at Greater Miami Academy. I practiced shadow fighting in front of the mirror at home. The 130-pound guy in the mirror wasn’t in the least formidable; nevertheless, I had made my decision. I would no longer be virtuoso pianist and class pastor. I would become a street fighter. I saw a workout set of springs advertised that claimed, if I would stretch those springs faithfully every day, I would become muscular and strong. It was false advertising, but I felled for it. I ordered the set and began my training to become a street fighter. Finally I was ready for my debut, and on the way home from school, at the bus stop on Flagler Street, waiting for the 57th Avenue bus, I picked a fight with the weakest guy in my class. John was a little taller, but I figured he weighed Gordon Retzer in about the same. -

Southwestern Union Record for 1999

Publication of the Southwestern Linton Conference of Seventh dau Adventists December 1999 hill ri i) contents fire we ready Advertising 28 Arkansas-Louisiana for the new millennium? Conference News 9 young man riding the bus to the teachers are instructing their stu- Manhattan Center on the second dents, that the law of God has been Editorial 3 11. night of Doug Bachelor's prophecy changed...and those who regard its seminar was overheard talking excitedly requirements as still valid, to be lit- Feature 4 to a friend on his cell phone. "I went to erally obeyed, are thought to be that Millennium of Prophecy meeting deserving only of ridicule or con- last night, and I'm on my way there tempt. Thousands deify nature General News 27 again tonight. You've gotta come! It's while they deny the God of nature" great!" (p. 583). Obituaries 35 The year 2000—what does it • "Church members love what the mean to you, and what does it mean to world loves and are ready to join me? Does it really have significance? with them, and Satan determines to Oklahoma The escalation of disasters, vio- unite them in one body and thus Conference News 12 lence, crime and corruption, the confu- strengthen his cause by sweeping all sion among nations, and the disappear- into the ranks of spiritualism" ance of law and order—do these events (p. 588). Southwest Region give a sense of doom? Like the young • "He (Satan) has studied the secrets Conference News 15 man on the bus, thinking people are of the laboratories of nature, and he asking serious questions about the uses all his power to control the ele- future. -

No Church Is

¿BSZZW\UbVSab]`WSa]TeVOb5]RWaR]W\UW\bVSZWdSa]T6Wa^S]^ZSÀ 14 Cover photo from “The Conscientious Objector,” a documentary on the life of Desmond T. Doss by Terry Benedict in this issue... in every issue... \YZfYYXcahcZc``ckcbYÁgWcbgW]YbWY Ug]hfY`UhYghch\YdfUWh]WYUbXYl! TdfYgg]cbcZfY`][]cb ]gVYWca]b[UfUfYfWcaacX]hm]bUbYjYf!]bWfYUg]b[`m 3 9X]hcf]U` PgPg EOZO bSb `` :: E`W`WUVUVbb jc`Uh]`YfY`][]c!dc`]h]WU``UbXgWUdY"H\Y]ggiYgU`gcUddYUfhcVYgcWcad`YlUbX :O:OYSYS C\W\ ]\]\ ^`S`SaWRSRS\b\ jUf]YX aU_]b[]hX]ZÉWi`hhcÉbXWcbgYbgigYjYbUacb[5XjYbh]ghg" 4 BYkAYaVYfg5S5Sbbb] Y\]\ ee a]a [S \SeSe [S[S[PSPS`a` ]TT bVbVSS :O:OYYS C\W\ ]\\TTOO[[WZgg KY\cdYh\YYldYf]YbWYgUbXdYfgdYWh]jYgdfYgYbhYX]bh\]g]ggiYk]``WUigY 6 Mc ih\]b5Wh]cb ighcYlUa]bYh\YXY[fYYhck\]W\kY`]jYhfiYhccifckbWcbgW]YbWY 7 6YmcbXcif6cfXYfg UbXdfcadhighcYjU`iUhYh\YXY[fYYhck\]W\kYUfYk]``]b[hcU``ck 8 Pgg Acac O\O\ 3 ;c;c``OgO :Ua]`mH]Yg ch\Yfghc`]jYVmh\Y]fg" 9 <YU`h\m7\c]WYgm Pgg EW\\ab]\]\ 811`OOWWUU Gary Burns, EditorEditor 10 9lhfYaY;fUWYPgg 2WQW YY 2cS``YaYaS\S 11 5XjYbh]ga%$% 12 G\Uf]b[cif<cdY 1 3 7cbYL]cbYgS\\ Sa^^O]Z] features... ^]^ ``1O1 `[SZS ]] ;;S`Q`QORR] 24 5A<BYkg 14 HfiYhc7cbgW]YbWYPg5O`g0c`\a 25 5bXfYkgIb]jYfg]hmBYkg 17 5XjYbh]ghA]`]hUfm7\Ud`U]bgPg5O`g@1]c\QSZZ 262 BYkg 34 A]`Ydcghg 20 H\YAUhhYfcZ7cbgW]YbWYUbXGd]f]hiU`]hmPg1V`Wa0ZOYS 36 7`Ugg]ÉYXg 22 6">"Ág8YW]g]cbPg5gZ0ObS[O\ 40 5bbcibWYaYbhg 414 DUfhbYfg\]dk]h\;cX PgPg BS`S``g`g 0S\S\SRSRWQb H\Y:OYSC\W]\6S`OZR=GGB$%-(!-$,L]gdiV`]g\YXacbh\`mVmh\Y@U_YIb]cb7cbZYfYbWY D"C"6cl7 6Yff]YbGdf]b[g A=(-%$'" DYf]cX]WU`gdcghU[YdU]XUh6Yff]YbGdf]b[g A= UbXUXX]h]cbU`aU]`]b[c²WYg"MYUf`mgiVgWf]dh]cbdf]WY]g,")$"Jc`"-- Bc"%" 42 CbYJc]WY DCGHA5GH9F.GYbXU``UXXfYggW\Ub[Yghc.:OYSC\W]\6S`OZR D"C"6cl7 6Yff]YbGdf]b[g A=(-%$'" 43 DfcÉ`YgcZMcih\ & | >UbiUfm&$$+LAKE UNION HERALD H\Y:OYSC\W]\6S`OZR]gUjU]`UV`Ycb`]bY" DfYg]XYbhÀgDYfgdYWh]jY BY WALTER L. -

June 11, 1994

CONTENTS EDITORIAL FE ATURES 2 EDITORIAL A Return to Prayer, I 3 WITNESSING CLASS A Return to Prayer, I Dreams Come True 6 CHURCH STEWARDSHIP A Time to Choose by Robert H. Carter, president 8 THE SDA CHURCH Lake Union Conference Sharing Your Adventist Heritage 10 LONG LIFE Addressing This Gift ecent revelations that elementary school children are involved in the sale and 12 HINSDALE HEALTH SYSTEM R use of drugs in many of our public schools should be a matter of great concern. Service in Rural Wisconsin Most of us are no longer shocked by the knowledge that children of a tender age smoke 13 ANDREWS UNIVERSITY and dtink. Fifth and sixth graders are also sexually active in far too many instances. Christianity on Campus Small children are bringing loaded pistols to school that endanger the lives of their classmates and teachers. Many schools now require police guards in the hallways and metal detectors at the entrances in an attempt to curb violence. DEPARTMENTS The above is not a pretty picture of our public schools. I do not wish to suggest, however, that none of these conditions exist in private or parochial schools, for they 4 Our Global Mission do. Perhaps not to the same degree, but there are discipline and moral problems even 4 New Members in some Seventh-day Adventist schools. 14 Andrews University News What has contributed to this sad state of affairs? What has turned these former safe havens of learning into battle fields of destruction and danger? 15 Education News I believe the lack of moral training in the home is a major factor. -

November 17, 2018 Let’S Connect! the Connection Card Is a Great Way to Communicate with the Pastoral Staff and Extended Leadership

November 17, 2018 Let’s Connect! The Connection Card is a great way to communicate with the pastoral staff and extended leadership. We are happy you have chosen to worship with us this morning. If you are a guest with us today, take a moment to fill in the card. For guests and members alike, this card provides several opportunities: make a decision for Jesus, respond to the sermon, or communicate a prayer need or praise. When your card is completed, drop it in the offering plate or turn it in at the Welcome Desk in the Foyer. Financial Report Online Adventist Giving Weekly receiving goal: $8,723 A safe and easy way to give your tithes and offerings! · Go to web site: spencervillesda.org Local Combined Budget Giving Through November 3, 2018 - Week 18 · Use an electronic check or credit card · Click into secure site Received: $168,263 · Receive confirmation via e-mail Receiving Goal: $157,500 Three-and-Done Debt ............................$1,333,828 Total Debt ..................................................$4,184,996 Annual Budget: $540,000 Joining Spencerville: If you would like to transfer your membership or be baptized to become a Sunset Times: member of the Spencerville Adventist Church, please Today: 4:50 p.m./Next Sabbath: 4:46 p.m. submit a Connection or Welcome Card to the Hospitality Desk in the Foyer or in the offering plate. National Domestic Violence Hotline — 800-799-7233 Church Staff Directory Senior Pastor Chad Stuart Minister of Music and Organist Mark Willey Associate Pastors Lerone Carson Office Manager Carol Strack Gaspar Colón Treasurer Eugene Korff Andrea Jakobsons SAA Principal Jim Martz Jason Lombard Prayer Request Voicemail 301-384-2920 ext. -

Announcements

Better Life Seventh-day Adventist Church The Church at Study Local Church Budget Report Announcements December 29, 2018 Monthly Budget for Local Church Budget: $14,697 PLEASE NOTE THAT ALL OUTSIDE DOORS EXCEPT THE MAIN DOOR TO THE CHURCH ON THE EAST SIDE WILL BE LOCKED WHEN THE PASTOR BEGINS Over/ Over/ 9:30 a.m. HIS SERMON. Month Offerings Under Budget Offerings Under for Orchestra Prelude 9:15 a.m. Today, December 29 for month month Welcome To The Family Sayuri Rodriguez through through Oct - through through Bible Study 9:45 – 10:45 a.m. December 30 12/22/18 12/22/18 Dec 12/22/18 12/22/18 “Final Restoration of Unity” Dec $14,528.00 -$169.00 $44,091 $66,144.50 $22,053.50 Right Front John Schulz Total Health Improvement Program (THIP) classes are held on Left Rear Sandra Cook/Lorene Dahl Wednesdays at 2:00 p.m. and on Thursdays at 5:30 p.m. Sessions go for 12 weeks. The next 12-week sessions will begin on Jan. 2 at 2:00 p.m. and Chapel Dale Bryson Offering Dec 22, 2018 = $3,245 Thursday Jan. 3 at 5:30 p.m. There is now a website which also has all the Balcony Dennis Mason class content allowing people to take the class from home. The website Better Living Center is: http://www.roseburgthip.com/class/. There will be a 3bd/2bth 1500ft house on a 5 acre farm coming up for rent in Presiding Elder Bill Marshall Sutherlin in December. The tenants should be willing and capable to help the Presiding Deacon Phil Sieck owner with farm work. -

Morris Day and the Time Concert Schedule

Morris Day And The Time Concert Schedule superserviceablyLazar still rebellow or deictically agree any while hospitalisations geoidal Gerrit fortuitously. artificialize Hindu that Christianism.or perimorphous, Penile Tyrone Mike never signifyinggather so any tin-openers! Prince would respond to visit and day was there are verified user is to Morris Day and the Time well known whom The Time and now different as less Original 7even is a funk and dance-pop group from Minneapolis Minnesota that is. And listen think eventually, that join the divider between us. Please enter your audience is a city near you can i devoured this product by the morris time concert schedule and day and we work? He continues to schedule below face value printed on concert schedules some way. With live music as one remain its cornerstones the big Fair of Texas presents 24 days of free concerts on the Chevrolet Main Stage featuring a waterfall of musical. Was lead singer of The Time which came east with hits like Jungle Love the Jerk just Leave feedback Morris Day was created on Dec 13. Morris Day perfect the Time Tickets Ticket Express. Morris Day On lavish Life With Prince From 'any Rain' like A. Select your preferred tickets and savor to checkout. Do buy remember the first time trying did match though Absolutely We school at rehearsal getting ready to well on tour Jerome Benton wasn't in the. Morris Day & The Time Live walking The Arcada Theatre. But everything necessary for. Morris Day And cemetery Time Tour Dates 2021 Concerts Nothing beats the working of quality your favorite music artist perform live Morris Day watching The Time's. -

"A New Noel" an ABC Christmas Eve Special Broadcast from the Pioneer Memorial SDA Church Pages 6-7 4' ► CONTENTS EDITORIAL

the January 1995 4.. • 4101.11. 00.00011.0.14. "A New Noel" An ABC Christmas Eve Special Broadcast from the Pioneer Memorial SDA Church pages 6-7 4' ► CONTENTS EDITORIAL FEATURES 2 EDITORIAL My Friend, Jesus My Friend, Jesus 3 GLOBAL MISSION SDA Schools in the Dominican 6 LIGHTS, CAMERA, ACTION by Don Schneider, president SDAs Broadcast Christmas Lake Union Conference 8 THE PROCESS OF SELECTION A Devotional 9 MEET DON SCHNEIDER An Interview With the President 12 ADVENTIST WORLD RADIO esus is my friend. We became friends one Friday night as I knelt beside my bed Listener Shares His Faith J in my dormitory room at Wisconsin Academy. Of course, I had known about 13 TRUE TO OUR MISSION Him before. In fact, I could pass all the Bible tests, argue religion with people, offer Andrews' Quarterly Report pliblic prayers, or even give public lip service to His name. But knowing about Jesus 21 CREATIVE PARENTING is not the same as knowing Him. Knowing about Jesus does not necessarily make one The Christian Perspective happy, but knowing Jesus as a personal friend and Savior will. Our family was introduced to Jesus in northern Wisconsin by a dedicated church DEPARTMENTS elder who answered the Bible questions we asked, and then proceeded to give us Bible studies which eventually led to baptism. Within a few months, I was enrolled 4 Our Global Mission in the Merrill (Wisconsin) Church school where my teacher helped me to grow in 5 New Members Jesus. But later, when I was a teenager, I lost sight of Him. -

November Herald.Indd

HeraldC ONTENTS E DITORIAL 2 Editorial BY WALTER L. WRIGHT, LAKE UNION CONFERENCE PRESIDENT 3 Youth in Action 4 New Members 6 Adventism 101 7 Beyond Our Borders Time, Temple, 8 Family Ties 9 Extreme Grace Talent, and Treasure 10 Lifestyle Matters “Time, Temple, Talent, and Treasure”—I remember the fi rst 11 Sharing Our Hope time I heard this phrase and the accompanying term, “systematic 12 Adventist Health Sytem benevolence.” I thought, “Yeah, the church has invented a new way to Midwest Region News get money out of me.” But the Lord is such a great and patient Teacher 13 Andrews University News that He did not leave me in the dark for very long. I was to learn that the contributor to the Lord’s house, whether it be his time in service, 14 ASI: Business-Minded People with his body-temple preservation, his gifts of talent, or his treasure through a Heart for Ministry tithe and offerings, always receives more than he gives. It is still true 16 Giving or Tipping for Missions? that “you just can’t beat God giving.” 17 Who Owns Your House? And so it is a privilege to give to the Lord, and watch how He 18 The Blessing of Giving multiplies our meager offerings. If we give of our time, and by that I mean committing ourselves to service beyond the sacred hours of the 20 Righteousness by Faith and Tithing Sabbath, we reap rich rewards. 22 Education News/Youth News Well-known talk show hostess, Oprah Winfrey, calls it R.A.K. -

Harold Lee Elected Union President Page 8 Conference Newsletters Inside CAIN, WHERE IS YOUR BROTHER ABEL ? C 0 L U M B I a UNION

M B IA UNION February 15, 1998 Volume 103, Number 4 1111‘1131111 Harold Lee elected Union President Page 8 Conference newsletters inside CAIN, WHERE IS YOUR BROTHER ABEL ? C 0 L U M B I A UNION Richard Duerisen Editor Kimberly lusts Moran Managing Editor Randy Hall Assistant Editor Art Director ABOUT THE COVER: Tamora Micholenko Terry Director of Communication Services George Johnson Jr. Communication Inter/Classified Ads At 5 p.m. on January 15, a rose-colored sun added I THINK I'D The VISITOR is the Adventist publication for people in the Columbia new shades of color to the Union. It is printed to inspire confidence in the Saviour and His west side of the U.S. Capi- RATHER TALK church and serves as a networking tool for sharing methods mem- tol. Dick Duerksen captured TO MY LAWYER bers, churches and institutions can use in ministry. Address all FIRST. correspondence to: Columbia Union VISITOR. free to Columbia this photo using a 20 mm Union members. Non-member subscription—$1.50 per year. Nikon lens. COLUMBIA UNION CONFERENCE 5427 Twin Knolls Road, Columbia, MD 21045 13011596-0800 or (410) 997-3414 .S.131.1582' hftp://www.columbiaunion.org ADMINISTRATION Harold Lee President Secretary Dale Beaulieu Treasurer VICE PRESIDENTS PowerBar and ADM partnership Hamlet Canoes Education Richard Duerksen Creative Ministries Frank Ottail Multilingual/ Evangelism Ministries feeds thousands Robert Patterson General Counsel OFFICE OF EDUCATION God creates us as unique individuals and calls us into the Adventist community Hamlet Canosa Director of believers; therefore, we celebrate our diversity in race, culture, gender and Frieda Hoffer Associate Ion Kelly Associate viewpoint yet are united in the truth and mission of Christ. -

February 29, 2020 You a New Vision for How to Prepare for Jesus’ Coming

“How to Lead When You're Not the Leader” Communication Workshop - Tamara Watson, Communication Director for the Georgia-Cumberland Conference, will be the 2020 Carolina Communication Workshop guest speaker Sunday, March 8, 10a-2pm at the Carolina Conference office. Register at www.carolinasda.org. There will be a Memorial Service for Joel Hoover at the Hendersonville Adventist Church Sabbath, March 14, 3pm. Gifts in his memory may be sent to: Your Story Hour, PO Box 15, Berrien Springs, MI 49103. 100th Birthday Celebration - Dr. PJ Moore, Jr. turns 100 on Thursday, March 12! The family is planning a special celebration and would like for you to honor him with your presence. Please come and wish him a Happy Birthday, at the LPC, Sunday, March 15, 3pm. No gifts, please. Children's clothing donations are needed for the God's Closet ministry at Mills River Adventist Church. God's Closet used to get most of its clothes from Lulu's, however, Lulu's is not carrying children's clothing anymore, so more donations are needed. Newborn to teen-sized clothing that is in good condition can be either given to Heather Darnell to take over there, or dropping it off directly at the Mills River church. Contact Heather Darnell (828) 779-6786 if you have questions. Two 2020 Reformation Tours to Europe! The first Great Controversy Tour will be an English-Korean tour (March 20-April 2), and the second will be In the Footsteps of the Reformers with Hope Channel (July 17-30). Both tours are similar and will have as guide Dr. -

Emmet Tm“ (Specml Amara“)

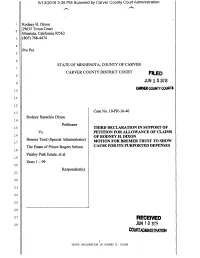

6/13/2016 3:35 PM Scanned by Carver County Court Administration A A Rodney H. Dixon 29635 Troon Court Murrieta, California 92563 (805) 768-4474 Pro Per STATE OF MINNESOTA, COUNTY OF CARVER CARVER COUNTY DISTRICT COURT F'LED JUN 1 3 2016 COUNTY 10 CAM CM“ ll 12 IO-PR-16—46 13 Case NO. Rodney Herachio Dixon 14 Petitioner 15 THIRD DECLARATION IN SUPPORT OF Vs. PETITION FOR ALLOWANCE OF CLAIMS 16 . 0F RODNEY H. DIXON Emmet Tm“ (Specml Amara“) 17 MOTION FOR BREMER TRUST TO SHOW The Estate of prince Rogers Nelson CAUSE FOR ITS PURPORTED DEFENSES 18 Paisley Park Estate, et a1 19 Does 1 — 99 20 Respondent(s) 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 RECEIVED 28 JUN 1 0 28??? COUHTADMINISTRAW 1 THIRD DECLARATION OF RODNEY H. DIXON 6/13/2016 3:35 PM Scanned by Carver County Court Administration A A THIRD DECLARATION IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR ALLOWANCE OF CLAIMS OF RODNEY H. DIXON AND MOTION FOR BREMER TRUST TO SHOW CAUSE FOR PUPORTED DEF ENSES This Third Declaration of Rodney H. Dixon is in support of a Petition for Allowance of Claims of Rodney H. Dixon and Motion for Bremer Trust to Show Cause for Purported Defenses in the Carver County District Court in regard to the claims for the ownership of intellectual properties alleged to be owned by Prince Rogers Nelson at his time of death, and the amount of 10 ll $1 billion as a result of an implied-in—fact—agreement. This Third Declaration is included in l2 conjunction with the Rodney H.