(Scotland) Bill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

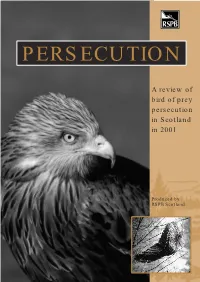

A Review of Bird of Prey Persecution in Scotland 2001

PERSECUTION A review of bird of prey persecution in Scotland in 2001 Produced by RSPB Scotland A Review of Bird of Prey Persecution in Scotland 2001 28 January 2003 wpo\ab\BOP1\5232 Birds of Prey Report 2001 Contents 1 Preamble 2 2 Recommendations 2 3 Introduction 3 4 Poisoning 4 5 Direct persecution other than poisoning 5 6 Investigation and prosecution 7 Poisoning incidents 7 Incidents other than poisoning 8 7 Discussion of the general nature of persecution offences8 The law 8 Comparative distribution of 2001 and past incidents 9 Published material that indicates likely offenders 10 Prosecutions 11 8 Identifiable trends in persecution 12 9 Conclusions 12 10 Acknowledgements 13 11 Appendices and Maps 13 Appendix A 13 Appendix B 15 Appendix C 15 Appendix D 18 Table 2 18 Map 1 23 Map 2 24 Map 3 25 Map 4 26 1 Birds of Prey Report 2001 1 Preamble The deliberate destruction of Scotland’s birds of prey has been a prominent issue for many decades. The practice of eliminating all the possible predators of game on shooting estates was a routine procedure in the 19th century with little or no regard to the conservation status of the targeted animals. This resulted in national and regional extinctions of a number of predatory birds and other animals. Many of these extirpated species have made significant recoveries in recent years either through natural re-colonisation or through re- introduction by humans. This implies a reduction in killing sufficient to allow these recoveries or facilitate re-introductions. This generally positive trend has not been universal. -

Human Rights and the Work of the Scottish Land Commission

Human Rights and the Work of the Scottish Land Commission A discussion paper Dr Kirsteen Shields May 2018 LAND LINES A series of independent discussion papers on land reform issues Background to the ‘Land Lines’ discussion papers The Scottish Land Commission has commissioned a series of independent discussion papers on key land reform issues. These papers are intended to stimulate public debate and to inform the Commission’s longer term research priorities. The Commission is looking at human rights as it is inherent in Scotland’s framework for land reform and underpins our Strategic Plan and Programme of Work. This, the fifth paper in the Land Lines series, is looking at the opportunities provided by land reform for further realisation of economic, social and cultural human rights. The opinions expressed, and any errors, in the papers are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Commission. About the Author Dr Kirsteen Shields is a Lecturer in International Law at the University of Edinburgh’s Global Academy on Agriculture and Food Security and was recently a Fullbright / Royal Society of Edinburgh Scholar at the University of Berkeley, California. She has advised the Scottish Parliament on land reform and human rights and was the first Academic Fellow to the Scottish Parliament’s Information Centre (SPICe) in 2016. LAND LINES A series of independent discussion papers on land reform issues Summary Keywords Community; property rights; land; human rights; economic; social; cultural Background This report provides a primer on key human rights developments and obligations relevant to land reform. It explains the evolution in approach to human rights that is embodied in the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2016 and it applies that approach to aspects of the Scottish Land Commission’s four strategic priorities. -

Inverness Local Plan Public Local Inquiry Report- Volume 3

TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) ACT 1997 REPORT OF PUBLIC LOCAL INQUIRY INTO OBJECTIONS TO THE INVERNESS LOCAL PLAN VOLUME 3 THE HINTERLAND AND THE RURAL DEVELOPMENT AREA Reporter: Janet M McNair MA(Hons) MPhil MRTPI File reference: IQD/2/270/7 Dates of the Inquiry: 14 April 2004 to 20 July 2004 CONTENTS VOLUME 3 Abbreviations The A96 Corridor Chapter 24 Land north and east of Balloch 24.1 Land between Balloch and Balmachree 24.2 Land at Lower Cullernie Farm Chapter 25 Inverness Airport and Dalcross Industrial Estate 25.1 Inverness Airport Economic Development Initiative 25.2 Airport Safeguarding 25.3 Extension to Dalcross Industrial Estate Chapter 26 Former fabrication yard at Ardersier Chapter 27 Morayhill Chapter 28 Lochside The Hinterland Chapter 29 Housing in the Countryside in the Hinterland 29.1 Background and context 29.2 objections to the local plan’s approach to individual and dispersed houses in the countryside in the Hinterland Objections relating to locations listed in Policy 6:1 29.3 Upper Myrtlefield 29.4 Cabrich 29.5 Easter Clunes 29.6 Culburnie 29.7 Ardendrain 29.8 Balnafoich 29.9 Daviot East 29.10 Leanach 29.11 Lentran House 29.12 Nairnside 29.13 Scaniport Objections relating to locations not listed in Policy 6.1 29.14 Blackpark Farm 29.15 Beauly Barnyards 29.16 Achmony, Balchraggan, Balmacaan, Bunloit, Drumbuie and Strone Chapter 30 Objections Regarding Settlement Expansion Rate in the Hinterland Chapter 31 Local centres in the Hinterland 31.1 Beauly 31.2 Drumnadrochit Chapter 32 Key Villages in the Hinterland -

Spice Briefing Land Reform in Scotland 03 June 2015 15/28 Alasdair Reid

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament Infor mation C entre l ogos. SPICe Briefing Land Reform in Scotland 03 June 2015 15/28 Alasdair Reid Clockwise from top: Isle of Gigha (Scottish Government 2012a); Integrated Landscape Buccleuch Estates (Scottish Land and Estates 2014a); Lambhill Stables and Forth and Clyde Canal, Glasgow (Lambhill Stables 2015). CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 SCOTLAND’S LAND ................................................................................................................................................ 4 WHAT IS LAND REFORM? ......................................................................................................................................... 5 LAND REFORM BEFORE SCOTTISH DEVOLUTION ............................................................................................... 6 LAND REFORM SINCE DEVOLUTION ...................................................................................................................... 8 LAND REFORM POLICY GROUP ........................................................................................................................... 8 LEGISLATION SINCE DEVOLUTION .................................................................................................................... -

Celtic Lands and Identities: Global and Local Implications”

“Celtic lands and identities: Global and Local Implications” The 2018 John F. Roatch Global Lecture on Social Policy and Practice, Arizona State University, College of Public Service and Community Solutions Phoenix, Arizona, USA, 23 March, 2018 Professor Frank Rennie The concept of “Think global, act local” is frequently attributed to the work of Patrick Geddes, a Scottish biologist, sociologist, philanthropist and pioneering town planner. He was an early champion of working with the environment, rather than working against it. The concept has since been applied to a very wide range of societal issues, but for today, I would just like to focus on its implications for local and national identity, in the recognition of a sense of place, and in determining a sense of responsibility for that place. I would then like to look at the social implications of that heightened sense of local and national identity. There is a particular word in the Gaelic language of my homeland for which is difficult to give a direct translation into English. “Buntanas” expresses sense of belonging, now simply in the present, but the concept of a person or community of people belonging to a certain area of land, a communal sense of embeddedness, and rootedness through family lineage and history of a community who belong to a certain place. This is contradistinction to the more usual Western concept of the land belonging to an individual person, of people owning the land in its entirety. In the poetry of the late Norman MacCaig, he asks… Who possesses this landscape? – The man who bought it or I who am possessed by it? I want to return to this theme in a few minutes, for I think that our relationships with the land is at the heart of the Celtic relationship with land and place. -

A Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2016 Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols Traci N. Billings University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, European History Commons, and the Medieval History Commons Recommended Citation Billings, Traci N., "Gender Reflections: a Reconsideration of Pictish Mirror and Comb Symbols" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1351. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1351 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2016 ABSTRACT GENDER REFLECTIONS: A RECONSIDERATION OF PICTISH MIRROR AND COMB SYMBOLS by Traci N. Billings The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2016 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold, PhD. The interpretation of prehistoric iconography is complicated by the tendency to project contemporary male/female gender dichotomies into the past. Pictish monumental stone sculpture in Scotland has been studied over the last 100 years. Traditionally, mirror and comb symbols found on some stones produced in Scotland between AD 400 and AD 900 have been interpreted as being associated exclusively with women and/or the female gender. This thesis re-examines this assumption in light of more recent work to offer a new interpretation of Pictish mirror and comb symbols and to suggest a larger context for their possible meaning. -

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-Àite Ann an Sgìre Prìomh Bhaile Na Gàidhealtachd

Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Place-Names of Inverness and Surrounding Area Ainmean-àite ann an sgìre prìomh bhaile na Gàidhealtachd Roddy Maclean Author: Roddy Maclean Photography: all images ©Roddy Maclean except cover photo ©Lorne Gill/NatureScot; p3 & p4 ©Somhairle MacDonald; p21 ©Calum Maclean. Maps: all maps reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/ except back cover and inside back cover © Ashworth Maps and Interpretation Ltd 2021. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2021. Design and Layout: Big Apple Graphics Ltd. Print: J Thomson Colour Printers Ltd. © Roddy Maclean 2021. All rights reserved Gu Aonghas Seumas Moireasdan, le gràdh is gean The place-names highlighted in this book can be viewed on an interactive online map - https://tinyurl.com/ybp6fjco Many thanks to Audrey and Tom Daines for creating it. This book is free but we encourage you to give a donation to the conservation charity Trees for Life towards the development of Gaelic interpretation at their new Dundreggan Rewilding Centre. Please visit the JustGiving page: www.justgiving.com/trees-for-life ISBN 978-1-78391-957-4 Published by NatureScot www.nature.scot Tel: 01738 444177 Cover photograph: The mouth of the River Ness – which [email protected] gives the city its name – as seen from the air. Beyond are www.nature.scot Muirtown Basin, Craig Phadrig and the lands of the Aird. Central Inverness from the air, looking towards the Beauly Firth. Above the Ness Islands, looking south down the Great Glen. -

Strategy Report and Recommendations from the 1 Million Acre Short Life Working Group

One Million Acres by 2020 Strategy report and recommendations from the 1 Million Acre Short Life Working Group December 2015 1 Contents 1. Why 1 million acres? What’s the case for action? ......................................................... 3 1.1 Background ......................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 SLWG – remit & structure ............................................................................................... 5 1.3 Evidence – benefits of CLO ............................................................................................ 8 1.3.1 Benefits that are specific to community ownership and may not be realised through other forms of community management ......................................... 8 1.3.2 Benefits of community ownership for communities as landowners ....... 9 1.3.3 Benefits for the broader community ................................................................ 11 1.3.4 Conclusion ................................................................................................................. 14 1.4 Definition – What do we mean by community land ownership? .................... 15 1.5 How much land is currently in community ownership? .................................... 16 2. Vision & Principles .................................................................................................................. 19 3. Policy Context ......................................................................................................................... -

Foyers Fools Triathlon 2008

December 2008 Issue 45 Foyers Fools Triathlon 2008 On Saturday 8th November, anyone out and about Inside this issue: around Foyers would have noticed some unusual ac- Letters from a Large Loch tivity on the loch. Strange lycra-clad fools, bursting 3 with fitness and fired by competition, were to be seen Post Office Apology 5 haring about in all directions and on both sides of the loch. What on earth was going on?! Farraline Wedding 6 Well, these were fools indeed, “Foyers Fools” to be Boleskine Wetland Project 7 precise, because Saturday saw the launch of the inau- Stratherrick Primary School 9 gural “Foyers Fools Triathlon”, a 25 mile adventure racing extravaganza of biking, kayaking, mountain Council Minutes 10 running and bacon butty eating. Christian comment 16 Competitors had to mountain bike the rough trail from BB accounts 18 Allt na Goibhre to Lower Foyers, ditch the bikes, leap into their shiny colourful kayaks and paddle like de- Bus Time Tables 19 mons across the Loch. Once on the north side they Wade Bridge Update 20 donned their safety packs, waded the culvert under Adverts 21-24 1 the A82 and then bust a gut to run to the summit of Meall Fuar-mhonaidh, 700m up in the sky. The return trip to the finish, body depleted of energy and legs racked with cramp, was a true test of survival of the fittest. Organisers were mindful of the masochistic preferences of competitors such as these and therefore set the finish line back at the top of the Allt na Goibhre hill.....this is known as an Alpine finish. -

2015 MAGAZINE:Layout 1

Clan Chattan Association Magazine March 2015 Touch Not – Magazine of the Clan Chattan Association Since our AGM last year, four new members have been elected to Council to assist in organisational matters of the Association. They are: Anne Fraser from Inverness, Rob Macintosh from Boston, David Mackintosh from Essex and Augusta Maclean of Dochgarroch from Edinburgh and Nigel Mac-Fall has also been elected Honorary Vice President. You will see their profiles within the pages of the magazine. I am sure all members THE ANNUAL GATHERING will wish them well and I look forward to their support and knowledge which they will OF THE CLAN CHATTAN bring to the Association. ASSOCIATION I want to thank Nigel Mac-Fall for his continued support and contribution. His 6-8 August 2015 design changes to the imagery of how the Association will be acknowledged in the The Annual General Meeting of future, were presented and adopted by The Clan Chattan Association Council towards the end of last year. The will take place in the Lochardil results of these changes are detailed within House Hotel Chairman’s welcome these pages and I am confident that members will agree that the changes made can only Dear Clansfolk Thursday 6 August enhance the way in which the Association is extend a warm welcome to you all in this 4pm: Gather together. perceived and recognised. the 4th edition of Touch Not. With so 5pm: The AGM of the Clan Imany tragedies happening around the Our Gathering in August. We are planning to world, I sincerely hope this publication brings have a 2 course meal and some entertainment Chattan Association a little extra joy to you wherever you are. -

Agrarian Reform and Agricultural Improvement in Lowland Scotland, 1750-1850

AGRARIAN REFORM AND AGRICULTURAL IMPROVEMENT IN LOWLAND SCOTLAND, 1750-1850 A Thesis by JOSHUA DAVID CLARK HADDIX Submitted to the Graduate School at Appalachian State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2013 Department of History AGRARIAN REFORM AND AGRICULTURAL IMPROVEMENT IN LOWLAND SCOTLAND, 1750-1850 A Thesis by JOSHUA DAVID CLARK HADDIX May 2013 APPROVED BY: Michael Turner Chairperson, Thesis Committee Jari Eloranta Member, Thesis Committee Jason White Member, Thesis Committee Lucinda McCray Beier Chairperson, Department of History Edelma D. Huntley Dean, Cratis Williams Graduate School Copyright by Joshua David Clark Haddix 2013 All Rights Reserved Abstract AGRARIAN REFORM AND AGRICULTURAL IMPROVEMENT IN LOWLAND SCOTLAND, 1750-1850 Joshua David Clark Haddix B.A., University of Cincinnati M.A., Appalachian State University Chairperson: Dr. Michael Turner Lowland Scotland underwent massive changes between 1750 and 1850. Agrarian improvement and land enclosure changed the way Scottish farmers and laborers used and thought about the land. This, in turn, had a major impact on industrialization, urbanization, and emigration. Predominantly, those in charge of implementing these wide-reaching changes were middle-class tenant farmers seeking to improve their social status. The power of these estate partitioners, or overseers, increased in the Lowlands throughout the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. They were integral to the improvement process in the Lowlands. They often saw both sides of agrarian reform, documenting it as such. By 1850, Lowland Scotland was one of the most industrialized and enlightened sectors of Europe; a century earlier it had been one of the least. -

The Land Reform (Scotland) Bill 2015 with International Approaches to Similar Issues

The Scottish Parliament and Scottish Parliament Infor mation C entre l ogos. SPICe Briefing International Perspectives on Land Reform 10 July 2015 15/38 Samantha Pollock This briefing considers the current patterns of land ownership, governance, use and management in Scotland, and compares them with those of other countries around the world. It compares the proposals of the Land Reform (Scotland) Bill 2015 with international approaches to similar issues. Clockwise from top left (Wikimedia Commons image credits in brackets): wind turbines on Eigg (W. L. Tarbert); red deer (Catti Maurizio); Swiss cadastral map (FSGeo); corn field in France (Ex0artefact). CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 SCOTLAND IN CONTEXT ........................................................................................................................................... 5 PATTERNS OF LAND OWNERSHIP ...................................................................................................................... 6 LOCAL GOVERNMENT STRUCTURES AND THE ROLE OF COMMUNITIES..................................................... 8 THE 2003 ACT: ACCESS TO LAND, COMMUNITY AND CROFTING COMMUNITY RIGHT TO BUY............... 10 Access to Land ..................................................................................................................................................