Approaching the Analysis of Post-1945 Music: Pedagogical Considerations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amjad Ali Khan & Sharon Isbin

SUMMER 2 0 2 1 Contents 2 Welcome to Caramoor / Letter from the CEO and Chairman 3 Summer 2021 Calendar 8 Eat, Drink, & Listen! 9 Playing to Caramoor’s Strengths by Kathy Schuman 12 Meet Caramoor’s new CEO, Edward J. Lewis III 14 Introducing in“C”, Trimpin’s new sound art sculpture 17 Updating the Rosen House for the 2021 Season by Roanne Wilcox PROGRAM PAGES 20 Highlights from Our Recent Special Events 22 Become a Member 24 Thank You to Our Donors 32 Thank You to Our Volunteers 33 Caramoor Leadership 34 Caramoor Staff Cover Photo: Gabe Palacio ©2021 Caramoor Center for Music & the Arts General Information 914.232.5035 149 Girdle Ridge Road Box Office 914.232.1252 PO Box 816 caramoor.org Katonah, NY 10536 Program Magazine Staff Caramoor Grounds & Performance Photos Laura Schiller, Publications Editor Gabe Palacio Photography, Katonah, NY Adam Neumann, aanstudio.com, Design gabepalacio.com Tahra Delfin,Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Brittany Laughlin, Director of Marketing & Communications Roslyn Wertheimer, Marketing Manager Sean Jones, Marketing Coordinator Caramoor / 1 Dear Friends, It is with great joy and excitement that we welcome you back to Caramoor for our Summer 2021 season. We are so grateful that you have chosen to join us for the return of live concerts as we reopen our Venetian Theater and beautiful grounds to the public. We are thrilled to present a full summer of 35 live in-person performances – seven weeks of the ‘official’ season followed by two post-season concert series. This season we are proud to showcase our commitment to adventurous programming, including two Caramoor-commissioned world premieres, three U.S. -

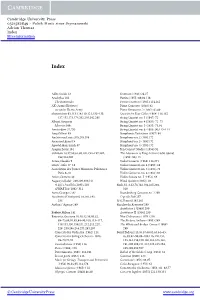

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Graå»Yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Gra#yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions: From a Perspective of Music Performance Hui-Yun (Yi-Chen) Chung Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GRAŻYNA BACEWICZ AND HER VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS- FROM A PERSPECTIVE OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE By HUI-YUN (YI-CHEN) CHUNG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Hui‐Yun Chung defended this treatise on November 3, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eliot Chapo Professor Directing Treatise James Mathes University Representative Melanie Punter Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above‐named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my beloved family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deep gratitude and thanks to Professor Eliot Chapo for his support and guidance in the completion of my treatise. I also thank my committee members, Dr. James Mathes and Professor Melanie Punter, for their time, support and collective wisdom throughout this process. I would like to give special thanks to my previous violin teacher, Andrzej Grabiec, for his encouragement and inspiration. I wish to acknowledge my great debt to Dr. John Ho and Lucy Ho, whose kindly support plays a crucial role in my graduate study. I am grateful to Shih‐Ni Sun and Ming‐Shiow Huang for their warm‐hearted help. -

Developing Sound Spatialization Tools for Musical Applications with Emphasis on Sweet Spot and Off-Center Perception

Sweet [re]production: Developing sound spatialization tools for musical applications with emphasis on sweet spot and off-center perception Nils Peters Music Technology Area Department of Music Research Schulich School of Music McGill University Montreal, QC, Canada October 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. c 2010 Nils Peters 2010/10/26 i Abstract This dissertation investigates spatial sound production and reproduction technology as a mediator between music creator and listener. Listening experiments investigate the per- ception of spatialized music as a function of the listening position in surround-sound loud- speaker setups. Over the last 50 years, many spatial sound rendering applications have been developed and proposed to artists. Unfortunately, the literature suggests that artists hardly exploit the possibilities offered by novel spatial sound technologies. Another typical drawback of many sound rendering techniques in the context of larger audiences is that most listeners perceive a degraded sound image: spatial sound reproduction is best at a particular listening position, also known as the sweet spot. Structured in three parts, this dissertation systematically investigates both problems with the objective of making spatial audio technology more applicable for artistic purposes and proposing technical solutions for spatial sound reproductions for larger audiences. The first part investigates the relationship between composers and spatial audio tech- nology through a survey on the compositional use of spatialization, seeking to understand how composers use spatialization, what spatial aspects are essential and what functionali- ties spatial audio systems should strive to include. The second part describes the development process of spatializaton tools for musical applications and presents a technical concept. -

Bibliographie Stockhausen 1952-2013 Engl

Stockhausen-Bibliography 1952-2013 [June 2013] The following bibliography alphabetically lists the authors who have written secondary literature about Karlheinz Stockhausen’s oeuvre: monographs, articles in books, periodicals and dictionaries, comprehensive works in which Stockhausen’s oeuvre is examined in detail. Reviews, contributions to concert programmes and publications in daily and weekly newspapers are only mentioned if they are considered to have reference value. Stockhausen’s own texts are not included, and conversations and interviews are only partly listed. Several works by the same author are listed consecutively in chronological order. When the name of the author was not available, the titel was listed alphabetically. This list includes the bibliographies that were published in Texte zur Musik, Vol. 6 (compiled by Chr. von Blumröder and H. Henck) and Vol. 10 (Chr. von Blumröder, R. Sengstock, D. Schwerdtfeger), and was supplemented and up-dated until 2013 (M. Luckas, I. Misch). Abkürzungen und Siglen / Abbreviations and Sigla AfMw. Archiv für Musikwissenschaft / Archive for Musicology Aufl. Auflage / printing Ausg. Ausgabe / edition Bd., Bde Band, Bände / volume, volumes Beitr. Beitrag / contribution BzAfMw. Beihefte zum Archiv für Musikwissenschaft / Supplementary booklets for the Archive for Musicology ders., dies. derselbe, dieselbe / the same DMT Dansk musiktidsskrift dt. deutsch / German eng. englisch / English erw. erweitert / supplemented Ffm. Frankfurt am Main / Frankfurt FP Feedback Papers frz. französisch / French H. Heft / booklet, issue Hbg Hamburg hg. herausgegeben / edited HmT Handwörterbuch der musikalischen Terminologie, hg. v. H. H. Eggebrecht, Wiesbaden 1972–1983, Stuttgart 1984–2006 / Hand Dictionary of Musical Terminology Ins. Institut / Institute jap. japanisch / Japanese Ldn London 1 ML Music and Letters MR The Music Review MT The Musical Times MuB Musik und Bildung Mw. -

Rmc193chiprograml5.Pdf

SATURDAY APRIL 29, 2017 | 7:30 PM | ROCKEFELLER CHAPEL A TRIPTYCH: Earth, Moon, Peace Works of Augusta Read Thomas Played by Spektral Quartet and Third Coast Percussion ROCKEFELLER CHAPEL | UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OF UNIVERSITY 2 PROGRAM The program is performed without intermission, although there will be brief pauses for resetting the stage. You are warmly invited to a wine and cheese reception here in the Chapel after the concert, with refreshments served from the west transept. You will also find CDs on sale. RAINBOW BRIDGE TO PARADISE SELENE Moon Chariot Rituals 2016 2015 3 Russell Rolen CELLO Spektral Quartet Third Coast Percussion and CHI CHI | A TRIPTYCH: EARTH, MOON, PEACE CHI for string quartet RESOUNDING EARTH 2017 World première 2012 I CHI vital life force I INVOCATION pulse radiance II AURA atmospheres, colors, vibrations II PRAYER star dust orbits III MERIDIANS zeniths III MANTRA ceremonial time shapes IV CHAKRAS center of spiritual power in the body IV REVERIE CARILLON crystal lattice Spektral Quartet Third Coast Percussion Clara Lyon VIOLIN David Skidmore Maeve Feinberg VIOLIN Peter Martin Doyle Armbrust VIOLA Robert Dillon Russell Rolen CELLO Sean Connors ABOUT THIS CONCERT Like most works of art, tonight’s concert came into Enter Spektral Quartet (or re-enter, for this being through the confluence of flashes of desire, conversation also had begun, allegro con spirito, some snippets of conversation, and the sudden alignment of eons before). On March 7, 2015, the cosmic lights went energies sparked by the commissioning of a new work. green and we knew we had a program: Selene, to be The flash of desire came just over three years ago. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

Symphony and Symphonic Thinking in Polish Music After 1956 Beata

Symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music after 1956 Beata Boleslawska-Lewandowska UMI Number: U584419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584419 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signedf.............................................................................. (candidate) fa u e 2 o o f Date: Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed:.*............................................................................. (candidate) 23> Date: Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: ............................................................................. (candidate) J S liiwc Date:................................................................................. ABSTRACT This thesis aims to contribute to the exploration and understanding of the development of the symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music in the second half of the twentieth century. -

Eric Chasalow/Over the Edge New World Records 80440 in Art, One

Eric Chasalow/Over the Edge New World Records 80440 In art, one and one at times make three. In art for the ear, and particularly with acoustic in combination with electronically-created sounds, the listener tends to hear rather more than a lockstep summation of parts. And it's perhaps this phantom dimension that most intrigues the listener. Again perhaps, as in a difficult love affair, a resonance arises from the antipodal aspects of seeming incompatibility and obviously compelling attraction. One is therefore given to approach music so conceived as forever newly plowed ground. Odd, then, in terms of expectation, that the first electro-acoustic compositions incorporating magnetic tape appeared (as I write) just over forty years ago: New Grove cites Bruno Maderna's aptly titled Musica su due dimensione I, for flute and tape, and Edgard Varese's Deserts of 1950-54, for orchestra and tape, as among the earliest examples. Earlier still, in 1939, before the advent of magnetic tape, John Cage composed his Imaginary Landscape No. 1, for piano, Chinese cymbal, and two variable-speed turntables. Significant music marks the way as milestones, with regard particularly to this CD. Karlheinz Stockhausen's 1959-60 version of Kontakte, for tape, piano, and percussion; Milton Babbitt's 1963-64 Philomel, for soprano, recorded soprano, and synthesized tape; Babbitt's 1974 Reflections, for piano and synthesized tape; Roger Reynolds's Transfigured Wind IV from 1985, for flute, computer, and tape; and Mario Davidovsky's ten Synchronisms, for a variety of solo instruments, ensemble combinations, and tape. Eric Chasalow's choice to study with Davidovsky is significant. -

1 Luigi Nono's Transformation, Creation, and Discovery of Musical Space

Luigi Nono's transformation, creation, and discovery of musical space Hyun Höchsmann [Visiting Professor, East China Normal University, Shanghai] Abstract: It is the inaudible, the unheard that does not fill the space but discovers the space, uncovers the space as if we too have become part of sound and we were sounding ourselves (Luigi Nono). Emphasising the necessity for contemporary music to 'intervene in the sonic reality of our time', Nono strove to expand the conception of musical space in three directions: the transformation of non-musical space with the performance of his music in factories and prisons, the creation of a new musical space for the opera, Prometeo, and the discovery of the inner musical space of sound and silence, 'the inaudible, the unheard', in which we 'become part of sound' and we are 'sounding ourselves'. Nono aimed at 'the composition of music that wants to restore infinite possibilities in listening today, by use of non- geometrical space'. With the conception of opera as 'azione scenica' (stage activity) and a 'theatre of consciousness', Nono's 'musical space' for the performance of Prometeo was realised within a colossal wooden structure (by Renzo Piano) combining the stage, the set, and the orchestra pit into a single element. With the conviction that it is the composer's and the listener's responsibility to recognise how every sound is politically charged by its historical associations, Nono affirmed the simultaneity of musical invention and moral commitment and political action for justice and freedom. _____________________________________________ 'A new way of thinking music' To wake up the ear, the eyes, human thinking, intelligence, the most exposed inwardness. -

Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(S): Miguel A

Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First- Century Students Author(s): Miguel A. Roig-Francolí Source: Indiana Theory Review, Vol. 33, No. 1-2 (Summer 2017), pp. 36-68 Published by: Indiana University Press on behalf of the Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/inditheorevi.33.1-2.02 Accessed: 03-09-2018 01:27 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Indiana University Press, Department of Music Theory, Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Indiana Theory Review This content downloaded from 129.74.250.206 on Mon, 03 Sep 2018 01:27:00 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms A Pedagogical and Psychological Challenge: Teaching Post-Tonal Music to Twenty-First-Century Students Miguel A. Roig-Francolí University of Cincinnati ost-tonal music has a pr problem among young musicians, and many not-so-young ones. Anyone who has recently taught a course on the theory and analysis of post-tonal music to a general Pmusic student population mostly made up of performers, be it at the undergraduate or master’s level, will probably immediately understand what the title of this article refers to.