The Role of Spermidine Synthase (Spds) and Spermine Synthase (Sms) in Regulating Triglyceride Storage in Drosophila

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

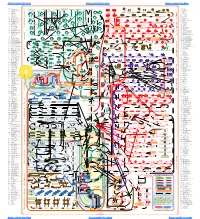

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Anamika Kothari Quang Ong Ron Caspi An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Peter D Karp Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Csac1394711Cyc: Candidatus Saccharibacteria bacterium RAAC3_TM7_1 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. Tim Holland TM7C00001G0420 TM7C00001G0109 TM7C00001G0953 TM7C00001G0666 TM7C00001G0203 TM7C00001G0886 TM7C00001G0113 TM7C00001G0247 TM7C00001G0735 TM7C00001G0001 TM7C00001G0509 TM7C00001G0264 TM7C00001G0176 TM7C00001G0342 TM7C00001G0055 TM7C00001G0120 TM7C00001G0642 TM7C00001G0837 TM7C00001G0101 TM7C00001G0559 TM7C00001G0810 TM7C00001G0656 TM7C00001G0180 TM7C00001G0742 TM7C00001G0128 TM7C00001G0831 TM7C00001G0517 TM7C00001G0238 TM7C00001G0079 TM7C00001G0111 TM7C00001G0961 TM7C00001G0743 TM7C00001G0893 TM7C00001G0630 TM7C00001G0360 TM7C00001G0616 TM7C00001G0162 TM7C00001G0006 TM7C00001G0365 TM7C00001G0596 TM7C00001G0141 TM7C00001G0689 TM7C00001G0273 TM7C00001G0126 TM7C00001G0717 TM7C00001G0110 TM7C00001G0278 TM7C00001G0734 TM7C00001G0444 TM7C00001G0019 TM7C00001G0381 TM7C00001G0874 TM7C00001G0318 TM7C00001G0451 TM7C00001G0306 TM7C00001G0928 TM7C00001G0622 TM7C00001G0150 TM7C00001G0439 TM7C00001G0233 TM7C00001G0462 TM7C00001G0421 TM7C00001G0220 TM7C00001G0276 TM7C00001G0054 TM7C00001G0419 TM7C00001G0252 TM7C00001G0592 TM7C00001G0628 TM7C00001G0200 TM7C00001G0709 TM7C00001G0025 TM7C00001G0846 TM7C00001G0163 TM7C00001G0142 TM7C00001G0895 TM7C00001G0930 Detoxification Carbohydrate Biosynthesis DNA combined with a 2'- di-trans,octa-cis a 2'- Amino Acid Degradation an L-methionyl- TM7C00001G0190 superpathway of pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotides de novo biosynthesis (E. -

Stem Cells® Original Article

® Stem Cells Original Article Properties of Pluripotent Human Embryonic Stem Cells BG01 and BG02 XIANMIN ZENG,a TAKUMI MIURA,b YONGQUAN LUO,b BHASKAR BHATTACHARYA,c BRIAN CONDIE,d JIA CHEN,a IRENE GINIS,b IAN LYONS,d JOSEF MEJIDO,c RAJ K. PURI,c MAHENDRA S. RAO,b WILLIAM J. FREEDa aCellular Neurobiology Research Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), Baltimore, Maryland, USA; bLaboratory of Neuroscience, National Institute of Aging, DHHS, Baltimore, Maryland, USA; cLaboratory of Molecular Tumor Biology, Division of Cellular and Gene Therapies, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration, Bethesda, Maryland, USA; dBresaGen Inc., Athens, Georgia, USA Key Words. Embryonic stem cells · Differentiation · Microarray ABSTRACT Human ES (hES) cell lines have only recently been compared with pooled human RNA. Ninety-two of these generated, and differences between human and mouse genes were also highly expressed in four other hES lines ES cells have been identified. In this manuscript we (TE05, GE01, GE09, and pooled samples derived from describe the properties of two human ES cell lines, GE01, GE09, and GE07). Included in the list are genes BG01 and BG02. By immunocytochemistry and reverse involved in cell signaling and development, metabolism, transcription polymerase chain reaction, undifferenti- transcription regulation, and many hypothetical pro- ated cells expressed markers that are characteristic of teins. Two focused arrays designed to examine tran- ES cells, including SSEA-3, SSEA-4, TRA-1-60, TRA-1- scripts associated with stem cells and with the 81, and OCT-3/4. Both cell lines were readily main- transforming growth factor-β superfamily were tained in an undifferentiated state and could employed to examine differentially expressed genes. -

Interactions of Natural Polyamines with Mammalian Proteins

Article in press - uncorrected proof BioMol Concepts, Vol. 2 (2011), pp. 79–94 • Copyright ᮊ by Walter de Gruyter • Berlin • New York. DOI 10.1515/BMC.2011.007 Review Interactions of natural polyamines with mammalian proteins Inge Schuster1 and Rita Bernhardt2,* ecules, such as phospholipids or nucleotides, thereby mas- 1 Institute for Theoretical Chemistry, University Vienna, sively affecting their structures and functions (9, 10). A-1090 Vienna, Austria Accordingly, polyamines were found to modulate numerous 2 Institute of Biochemistry, Saarland University, Campus regulatory processes in model systems that range from cel- B2.2, D-66123 Saarbru¨cken, Germany lular signaling to the control of gene expression and trans- lation and offer explanations for the obvious involvement of * Corresponding author polyamines in the regulation of cell growth, differentiation, e-mail: [email protected] and death wreviewed in (1, 11–14)x. The broad actions of polyamines on essential life functions are reflected by their effects on global gene expression. A recent study in a yeast Abstract mutant, an eukaryotic system comprising a three times small- er genome than mammalians, showed a significant regulation The ubiquitously expressed natural polyamines putrescine, of some 10% of the genome in (direct or indirect) response spermidine, and spermine are small, flexible cationic com- to spermidine or spermine (15). The essential requirement pounds that exert pleiotropic actions on various regulatory for polyamines and balanced levels of polyamines is under- systems and, accordingly, are essentially involved in diverse lined from studying knockouts that lack distinct genes life functions. These roles of polyamines result from their involved in polyamine synthesis and are not viable (10). -

Norspermine Substitutes for Thermospermine in the Control of Stem Elongation in Arabidopsis Thaliana

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector FEBS Letters 584 (2010) 3042–3046 journal homepage: www.FEBSLetters.org Norspermine substitutes for thermospermine in the control of stem elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana Jun-Ichi Kakehi a, Yoshitaka Kuwashiro a, Hiroyasu Motose a, Kazuei Igarashi b, Taku Takahashi a,* a Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Okayama University, Okayama 700-8530, Japan b Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chiba University, Chiba 260-8675, Japan article info abstract Article history: Thermospermine is a structural isomer of spermine and is required for stem elongation in Arabid- Received 26 March 2010 opsis thaliana. We noted the C3C3 arrangement of carbon chains in thermospermine (C3C3C4), Revised 16 May 2010 which is not present in spermine (C3C4C3), and examined if it is functionally replaced with norsper- Accepted 17 May 2010 mine (C3C3C3) or not. Exogenous application of norspermine to acl5, a mutant defective in the syn- Available online 24 May 2010 thesis of thermospermine, partially suppressed its dwarf phenotype, and down-regulated the level Edited by Ulf-Ingo Flügge of the acl5 transcript which is much higher than that of the ACL5 transcript in the wild type. Further- more, in the Zinnia culture, differentiation of mesophyll cells into tracheary elements was blocked by thermospermine and norspermine but not by spermine. Our results indicate that norspermine Keywords: Arabidopsis can functionally substitute for thermospermine. Thermospermine Ó 2010 Federation of European Biochemical Societies. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Norspermine Polyamine Stem elongation Xylem 1. -

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

Isolation and Characterization of S-Adenosylmethionine Synthase Gene from Cucumber and Responsive to Abiotic Stress T

Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 141 (2019) 431–445 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Plant Physiology and Biochemistry journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/plaphy Research article Isolation and characterization of S-Adenosylmethionine synthase gene from cucumber and responsive to abiotic stress T ∗ Mei-Wen Hea, Yu Wanga, Jian-Qiang Wua, Sheng Shua,b, Jin Suna,b, Shi-Rong Guoa,b, a Key Laboratory of Southern Vegetable Crop Genetic Improvement, Ministry of Agriculture, College of Horticulture, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, 210095, China b Suqian Academy of Protected Horticulture, Nanjing Agricultural University, Suqian, 223800, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: S-adenosylmethionine synthetase (SAMS) catalyzes methionine and ATP to generate S-adenosyl-L-methionine Cucumis sativus (SAM). In plants, accumulating SAMS genes have been characterized and the majority of them are reported to S-adenosylmethionine synthetase participate in development and stress response. In this study, two putative SAMS genes (CsSAMS1 and CsSAMS2) Gene expression were identified in cucumber (Cucumis Sativus L.). They displayed 95% similarity and had a high identity with Function their homologous of Arabidopsis thaliana and Nicotiana tabacum. The qRT-PCR test showed that CsSAMS1 was Salt stress predominantly expressed in stem, male flower, and young fruit, whereas CsSAMS2 was preferentially accumu- lated in stem and female flower. And they displayed differential expression profiles under stimuli, including NaCl, ABA, SA, MeJA, drought and low temperature. To elucidate the function of cucumber SAMS, the full- length CDS of CsSAMS1 was cloned, and prokaryotic expression system and transgenic materials were con- structed. Expressing CsSAMS1 in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) improved the growth of the engineered strain under salt stress. -

12) United States Patent (10

US007635572B2 (12) UnitedO States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,635,572 B2 Zhou et al. (45) Date of Patent: Dec. 22, 2009 (54) METHODS FOR CONDUCTING ASSAYS FOR 5,506,121 A 4/1996 Skerra et al. ENZYME ACTIVITY ON PROTEIN 5,510,270 A 4/1996 Fodor et al. MICROARRAYS 5,512,492 A 4/1996 Herron et al. 5,516,635 A 5/1996 Ekins et al. (75) Inventors: Fang X. Zhou, New Haven, CT (US); 5,532,128 A 7/1996 Eggers Barry Schweitzer, Cheshire, CT (US) 5,538,897 A 7/1996 Yates, III et al. s s 5,541,070 A 7/1996 Kauvar (73) Assignee: Life Technologies Corporation, .. S.E. al Carlsbad, CA (US) 5,585,069 A 12/1996 Zanzucchi et al. 5,585,639 A 12/1996 Dorsel et al. (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this 5,593,838 A 1/1997 Zanzucchi et al. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 5,605,662 A 2f1997 Heller et al. U.S.C. 154(b) by 0 days. 5,620,850 A 4/1997 Bamdad et al. 5,624,711 A 4/1997 Sundberg et al. (21) Appl. No.: 10/865,431 5,627,369 A 5/1997 Vestal et al. 5,629,213 A 5/1997 Kornguth et al. (22) Filed: Jun. 9, 2004 (Continued) (65) Prior Publication Data FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS US 2005/O118665 A1 Jun. 2, 2005 EP 596421 10, 1993 EP 0619321 12/1994 (51) Int. Cl. EP O664452 7, 1995 CI2O 1/50 (2006.01) EP O818467 1, 1998 (52) U.S. -

Generated by SRI International Pathway Tools Version 25.0 on Thu

Authors: Pallavi Subhraveti Ron Caspi Quang Ong Peter D Karp An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Ingrid Keseler Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. Gcf_900105695Cyc: Streptomyces melanosporofaciens DSM 40318 Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. -

Polyamines and Their Biosynthesis/Catabolism Genes Are Differentially Modulated in Response to Heat Versus Cold Stress in Tomato Leaves (Solanum Lycopersicum L.)

cells Article Polyamines and Their Biosynthesis/Catabolism Genes Are Differentially Modulated in Response to Heat Versus Cold Stress in Tomato Leaves (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Rakesh K. Upadhyay 1,2 , Tahira Fatima 2, Avtar K. Handa 2 and Autar K. Mattoo 1,* 1 Sustainable Agricultural Systems Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Henry A. Wallace Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, Beltsville, MD 20705-2350, USA; [email protected] 2 Center of Plant Biology, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Purdue University, W. Lafayette, IN 47907, USA; [email protected] (T.F.); [email protected] (A.K.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-301-504-6622 Received: 20 June 2020; Accepted: 20 July 2020; Published: 22 July 2020 Abstract: Polyamines (PAs) regulate growth in plants and modulate the whole plant life cycle. They have been associated with different abiotic and biotic stresses, but little is known about the molecular regulation involved. We quantified gene expression of PA anabolic and catabolic pathway enzymes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum cv. Ailsa Craig) leaves under heat versus cold stress. These include arginase 1 and 2, arginine decarboxylase 1 and 2, agmatine iminohydrolase/deiminase 1, N-carbamoyl putrescine amidase, two ornithine decarboxylases, three S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylases, two spermidine synthases; spermine synthase; flavin-dependent polyamine oxidases (SlPAO4-like and SlPAO2) and copper dependent amine oxidases (SlCuAO and SlCuAO-like). The spatiotemporal transcript abundances using qRT-PCR revealed presence of their transcripts in all tissues examined, with higher transcript levels observed for SAMDC1, SAMDC2 and ADC2 in most tissues. Cellular levels of free and conjugated forms of putrescine and spermidine were found to decline during heat stress while they increased in response to cold stress, revealing their differential responses. -

Supplemental Figures 04 12 2017

Jung et al. 1 SUPPLEMENTAL FIGURES 2 3 Supplemental Figure 1. Clinical relevance of natural product methyltransferases (NPMTs) in brain disorders. (A) 4 Table summarizing characteristics of 11 NPMTs using data derived from the TCGA GBM and Rembrandt datasets for 5 relative expression levels and survival. In addition, published studies of the 11 NPMTs are summarized. (B) The 1 Jung et al. 6 expression levels of 10 NPMTs in glioblastoma versus non‐tumor brain are displayed in a heatmap, ranked by 7 significance and expression levels. *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001. 8 2 Jung et al. 9 10 Supplemental Figure 2. Anatomical distribution of methyltransferase and metabolic signatures within 11 glioblastomas. The Ivy GAP dataset was downloaded and interrogated by histological structure for NNMT, NAMPT, 12 DNMT mRNA expression and selected gene expression signatures. The results are displayed on a heatmap. The 13 sample size of each histological region as indicated on the figure. 14 3 Jung et al. 15 16 Supplemental Figure 3. Altered expression of nicotinamide and nicotinate metabolism‐related enzymes in 17 glioblastoma. (A) Heatmap (fold change of expression) of whole 25 enzymes in the KEGG nicotinate and 18 nicotinamide metabolism gene set were analyzed in indicated glioblastoma expression datasets with Oncomine. 4 Jung et al. 19 Color bar intensity indicates percentile of fold change in glioblastoma relative to normal brain. (B) Nicotinamide and 20 nicotinate and methionine salvage pathways are displayed with the relative expression levels in glioblastoma 21 specimens in the TCGA GBM dataset indicated. 22 5 Jung et al. 23 24 Supplementary Figure 4. -

Generate Metabolic Map Poster

Authors: J. Michael Cherry Eurie Hong Benjamin Vincent Cynthia Krieger An online version of this diagram is available at BioCyc.org. Biosynthetic pathways are positioned in the left of the cytoplasm, degradative pathways on the right, and reactions not assigned to any pathway are in the far right of the cytoplasm. Transporters and membrane proteins are shown on the membrane. Rama Balakrishnan Ron Caspi Periplasmic (where appropriate) and extracellular reactions and proteins may also be shown. Pathways are colored according to their cellular function. YeastCyc: Saccharomyces cerevisiae S288c Cellular Overview Connections between pathways are omitted for legibility. -

Halfway to Hypusine—Structural Basis for Substrate Recognition by Human

biomolecules Article Half Way to Hypusine—Structural Basis for Substrate Recognition by Human Deoxyhypusine Synthase El˙zbietaW ˛ator , Piotr Wilk and Przemysław Grudnik * Malopolska Centre of Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, ul. Gronostajowa 7a, 30-387 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] (E.W.); [email protected] (P.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 January 2020; Accepted: 26 March 2020; Published: 30 March 2020 Abstract: Deoxyhypusine synthase (DHS) is a transferase enabling the formation of deoxyhypusine, which is the first, rate-limiting step of a unique post-translational modification: hypusination. DHS catalyses the transfer of a 4-aminobutyl moiety of polyamine spermidine to a specific lysine of eukaryotic translation factor 5A (eIF5A) precursor in a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-dependent manner. This modification occurs exclusively on one protein, eIF5A, and it is essential for cell proliferation. Malfunctions of the hypusination pathway, including those caused by mutations within the DHS encoding gene, are associated with conditions such as cancer or neurodegeneration. Here, we present a series of high-resolution crystal structures of human DHS. Structures were determined as the apoprotein, as well as ligand-bound states at high-resolutions ranging from 1.41 to 1.69 Å. By solving DHS in complex with its natural substrate spermidine (SPD), we identified the mode of substrate recognition. We also observed that other polyamines, namely spermine (SPM) and putrescine, bind DHS in a similar manner as SPD. Moreover, we performed activity assays showing that SPM could to some extent serve as an alternative DHS substrate. In contrast to previous studies, we demonstrate that no conformational changes occur in the DHS structure upon spermidine-binding.