Understanding the Dynamics of Produce Markets: Consumption and Consolidation Grow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Infogroup Business Listing File

Infogroup Business Listing File Company location: Omaha, Nebraska Web address: www.infousa.com Description: Infogroup collects information on approximately 11 million private and public US companies. Individual businesses are located by address geocoding—not all will have an exact location. The Esri geocoder integrates an address-based approach with more than eighty-one million residential and commercial U.S. address records from the NAVTEQ Point Addressing database. This database maps street addresses to a physical location so each address is a fixed point and not an interpolation from an address range. The geocoder uses address locators in a cascading fallback approach to ensure a match for as many records as possible. The primary locator utilizes the NAVTEQ Point Addressing database. The secondary locator utilizes the NAVTEQ Street Address Range database. Records that did not match fall back to the geocode provided by Infogroup. Businesses can be retrieved by their Standard Industrial Classification Code (SIC) as well as by North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Code and Location. The Infogroup Business File can be used for locating both competitors and marketing opportunities. This data is current as of July 2011. Fields: Note: Using the Identify a Business tool , click on a business in your map area to see these fields for an individual business. Fields marked in blue below are not visible in the business layer attribute table or exportable from Business Analyst. Company Name (Actual field name=CONAME) – The legal, incorporated business name. Example: ESRI, AT&T, IBM. Address – Physical address of location. The address field cannot be used for direct mailing purposes. -

1 Venditore 1500 W Chestnut St Washington, Pa 15301 1022

1 VENDITORE 1022 MARSHALL ENTERPRISES 10TH STREET MARKET 1500 W CHESTNUT ST INC 802 N 10TH ST WASHINGTON, PA 15301 1022-24 N MARSHALL ST ALLENTOWN, PA 18102 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19123 12TH STREET CANTINA 15TH STREET A-PLUS INC 1655 SUNNY I INC 913 OLD YORK RD 1501 MAUCH CHUNK RD 1655 S CHADWICK ST JENKINTOWN, PA 19046 ALLENTOWN, PA 18102 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19145 16781N'S MARKET 16TH STREET VARIETY 17 SQUARE THIRD ST PO BOX 155 1542 TASKER ST 17 ON THE SQUARE NU MINE, PA 16244 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19146 GETTYSBURG, PA 17325 1946 WEST DIAMOND INC 1ST ORIENTAL SUPERMARKET 2 B'S COUNTRY STORE 1946 W DIAMOND ST 1111 S 6TH ST 2746 S DARIEN ST PHILADELPHIA, PA 19121 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19147 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19148 20674NINE FARMS COUNTRY 220 PIT STOP 22ND STREET BROTHER'S STORE 4997 US HIGHWAY 220 GROCERY 1428 SEVEN VALLEYS RD HUGHESVILLE, PA 17737 755 S 22ND ST YORK, PA 17404 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19146 2345 RIDGE INC 25TH STREET MARKET 26TH STREET GROCERY 2345 RIDGE AVE 2300 N 25TH ST 2533 N 26TH ST PHILADELPHIA, PA 19121 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19132 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19132 2900-06 ENTERPRISES INC 3 T'S 307 MINI MART 2900-06 RIDGE AVE 3162 W ALLEGHENY AVE RTE 307 & 380 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19121 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19132 MOSCOW, PA 18444 40 STOP MINI MARKET 40TH STREET MARKET 414 FIRST & LAST STOP 4001 MARKET ST 1013 N 40TH ST RT 414 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19104 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19104 JERSEY MILL, PA 17739 42 FARM MARKET 46 MINI MARKET 4900 DISCOUNT ROUTE 42 4600 WOODLAND AVE 4810 SPRUCE ST UNITYVILLE, PA 17774 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19143 PHILADELPHIA, PA 19143 5 TWELVE FOOD MART 52ND -

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Inspired HEARTS Improve LIVES

2016 ANNUAL REPORT Inspired HEARTS LIVES Improve 2 Sacred Heart Foundation 2016 ANNUAL REPORT 4 DREW BAREFIELD A Champion for our Community 6 QUINT & RISHY STUDER Letter From Carol Making the Hospital a Reality CHILDREN’S MIRACLE 8 NETWORK HOSPITALS 30 Years of Partnership irst, I want to personally thank you for your support of our mission of care during the past year. 9 PANAMA CITY BEACH WALMART When we in healthcare have a vision, often it Committed to Making Miracles Happen is courage — a word derived from the French EVENT HIGHLIGHTS meaning “of heart” — that is required to bring 10 Bringing the Community Together Fthat vision to life. Indeed, our healing ministry is rooted in the courage of 12 CHARLES & SHIRLEY SIMPSON the Daughters of Charity, whose vision 101 years ago was Growing Healthcare on the Emerald Coast responsible for the first Sacred Heart Hospital. Today, we continue their legacy by ensuring that growth takes place 13 THE KUGELMAN FOUNDATION where it is most needed, as with the expansion of Sacred Heart Keeping the Legacy Alive Hospital on the Emerald Coast. Our President and CEO Susan Davis has exhibited great 14 ORDER OF THE CORNETTE GALA courage with her vision of the new Studer Family Children’s Honoring Philanthropic Leaders Hospital. This will ensure that the children of tomorrow, throughout our region, will have greater access to specialized 16 DONNA PITTMAN health care designed with a child’s needs in mind. Giving Back Like Drew Barefield, our patients and their families show amazing courage as they face surgeries and illnesses, and battle 17 DAVID SANSING through therapy and rehabilitation from, chemotherapy to Investing in Our Community’s Future cardiac care to joint replacement. -

MAY 2017 The

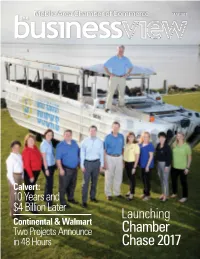

Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce MAY 2017 the Calvert: 10 Years and $4 Billion Later Launching Continental & Walmart Two Projects Announce Chamber in 48 Hours Chase 2017 the business view MAY 2017 1 We work for you. With technology, you want a partner, not a vendor. So we built the most accessible, highly responsive teams in our industry. Pair that with solutions o ering the highest levels of reliability and security and you have an ally that never stops working for you. O cial Provider of Telecommunication Solutions to the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce Leading technology. Close to home. business solutions cspire.com/business | [email protected] | 251.459.8999 C SpireTM and C Spire Business SolutionsTM are trademarks owned by Cellular South, Inc. Cellular South, Inc. and its a liates provide products and services under the C SpireTM and C Spire Business SolutionsTM brand. 2 the©2017 business C Spire. All rightsview reserved. MAY 2017 the Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce MAY 2017 | In this issue Volume XLVIII No. 4 ON THE COVER Kevin Carey, Trustmark Bank, is at the helm, From the Publisher - Bill Sisson chairing this year’s Chamber Chase effort. His crew consists of dozens of volunteers, a few of whom are pictured with him here. Gathering and Belonging See story on pages 14-15. Photo by Jeff Tesney. 4 News You Can Use Exciting changes are taking engage in networking. place all around us. Multi- If members no longer find 8 Small Business of the Month: generational workforces have value in traditional events, Payroll Vault become the norm in work should we drop some of these 11 Kevin Carey, Trustmark Bank, to Lead places throughout the world. -

Of Counsel: Alden L

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civ. No. 1:07-cv-01021-PLF ) WHOLE FOODS MARKET, INC., ) REDACTED - PUBLIC VERSION ) And ) ) WILD OATS MARKETS, INC., ) ) Defendants. ) ~~~~~~~~~~~~) JOINT MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES OF WHOLE FOODS MARKET, INC., AND WILD OATS MARKETS, INC. IN OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Paul T. Denis (DC Bar No. 437040) Paul H. Friedman (DC Bar No. 290635) Jeffrey W. Brennan (DC Bar No. 447438) James A. Fishkin (DC Bar No. 478958) Michael Farber (DC Bar No. 449215) Rebecca Dick (DC Bar No. 463197) DECHERTLLP 1775 I Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20006 Telephone: (202) 261-3430 Facsimile: (202) 261-3333 Of Counsel: Alden L. Atkins (DC Bar No. 393922) Neil W. Imus (DC Bar No. 394544) Roberta Lang John D. Taurman (DC Bar No. 133942) Vice-President of Legal Affairs and General Counsel VINSON & ELKINS L.L.P. Whole Foods Market, Inc. The Willard Office Building 550 Bowie Street 1455 Pennsylvania Avenue, N.W., Suite 600 Austin, TX Washington, DC 20004-1008 Telephone (202) 639-6500 Facsimile (202) 639-6604 Attorneys for Whole Foods Market, Inc. Clifford H. Aronson (DC Bar No. 335182) Thomas Pak (Pro Hae Vice) Matthew P. Hendrickson (Pro Hae Vice) SKADDEN, ARPS, SLATE, MEAGHER &FLOMLLP Four Times Square NewYork,NY 10036 Telephone: (212) 735-3000 [email protected] Gary A. MacDonald (DC Bar No. 418378) SKADDEN, ARPS, SLATE, MEAGHER &FlomLLP 1440 New York Avenue, N.W. Washington, DC 20005 Telephone: (202) 371-7000 [email protected] Terrence J. Walleck (Pro Hae Vice) 2224 Pacific Dr. -

Food Distribution in the United States the Struggle Between Independents

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 99 JUNE, 1951 No. 8 FOOD DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES, THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN INDEPENDENTS AND CHAINS By CARL H. FULDA t I. INTRODUCTION * The late Huey Long, contending for the enactment of a statute levying an occupation or license tax upon chain stores doing business in Louisiana, exclaimed in a speech: "I would rather have thieves and gangsters than chain stores inLouisiana." 1 In 1935, a few years later, the director of the National Association of Retail Grocers submitted a statement to the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives, I Associate Professor of Law, Rutgers University School of Law. J.U.D., 1931, Univ. of Freiburg, Germany; LL. B., 1938, Yale Univ. Member of the New York Bar, 1941. This study was originally prepared under the auspices of the Association of American Law Schools as one of a series of industry studies which the Association is sponsoring through its Committee on Auxiliary Business and Social Materials for use in courses on the antitrust laws. It has been separately published and copyrighted by the Association and is printed here by permission with some slight modifications. The study was undertaken at the suggestion of Professor Ralph F. Fuchs of Indiana University School of Law, chairman of the editorial group for the industry studies, to whom the writer is deeply indebted. His advice during the preparation of the study and his many suggestions for changes in the manuscript contributed greatly to the improvement of the text. Acknowledgments are also due to other members of the committee, particularly Professors Ralph S. -

Participating Chain Pharmacies

PARTICIPATING CHAIN PHARMACIES A & P Pharmacy Discount Drug Mart Hy-Vee, Drug Town Network Pharmacy Shoppers Pharmacy ABCO Pharmacy Doc's Drugs Ingles Pharmacy Oncology Pharmacy Services Shoprite Pharmacy Acme Pharmacy Drug Emporium Integrity Healthcare Services P&C Food Market Shurfine Pharmacy Acme, Lucky, Osco, Sav-on Drug Fair Kare Pharmacy Pacmed Clinic Pharmacy Smith's Food & Drug Center Albertson's Pharmacy Duane Reade Kash N' Karry Pharmacy Pamida Pharmacy Snyder Drug Stores Allcare Pharmacy Eagle Pharmacy Kelsey Seybold Clinic Pharmacy Park Nicollet Pharmacy Southern Family Markets Ambulatory Pharmaceutical Services Edgehill Drugs Kerr Drug Pathmark Stadtlander Pharmacy Anchor Pharmacy Express, Thrift, Treasury Keystone Medicine Chest Payless Pharmacy Standard Drug Company Appletree Pharmacy Fagen Pharmacy King Kullen Pharmacy Pediatric Services of America Star Pharmacy Arrow Pharmacy Fairview Pharmacy Kinney Drug's Pharma-Card Statscript Pharmacy Aurora Pharmacy Family Care Pharmacy Kleins Supermarket Pharmacy Pharmacy Plus Steele's Pharmacy B J's Pharmacy Family Drug Klinck, Drug Barn Presbyterian Retail Pharmacy Stop & Shop Pharmacy Bakers Pharmacy Family Fare Klingensmith's Drug Price Chopper Pharmacy Super D Bartell Drugs Family Pharmacy Kmart Pharmacy Price Less Drug Super Food Mart Basha's United Drug Fedco Drug Knight Drugs Price Wise, Piggly Wiggly Super Fresh Pharmacy Bel Air Pharmacy Finast Pharmacy Kohlls Pharmacy Prime Med Pharmacy Super RX Pharmacy Big Bear Pharmacy Food 4 Less Pharmacy Kopp Drug Publix Pharmacy -

Beyond the Veterans' Benefit Known As “Aid and Attendance”

75202-1 AlaBar.qxp_Lawyer 11/2/15 8:13 AM Page 357 November 2015 | Volume 76, Number 6 Beyond the Veterans’ Benefit Known As “Aid and Attendance” Page 374 75202-1 AlaBar.qxp_Lawyer 11/2/15 8:13 AM Page 358 The best malpractice insurance takes no time to find. AIM makes it easy. Dedicated to insuring practicing attorneys. Attorneys Insurance Mutual Telephone 205-980-0009 of the South® TollFree 800-526-1246 Fax 205-980-9009 200 Inverness Parkway Birmingham, Alabama 35242 wwwAttyslnsMut .com "Insuring and Serving Practicing Attorneys Since 1989" Copyright 2013 by Attorneys In surance Mutual of the South ® 75202-1 AlaBar.qxp_Lawyer 11/2/15 8:13 AM Page 359 75202-1 AlaBar.qxp_Lawyer 11/2/15 8:14 AM Page 360 >ĂƐƚŚĂŶĐĞ^ĞŵŝŶĂƌƐĨŽƌϮϬϭϱ DECEMBER ^ĂǀĞƚŚĞĂƚĞ͊^ƚĂƌƚϮϬϭϲŽīƌŝŐŚƚǁŝƚŚ ŽŶĞŽĨŽƵƌŐƌĞĂƚƐƉƌŝŶŐƉƌŽŐƌĂŵƐ͘ 2 Alabama Update Tuscaloosa JANUARY 4 Estate Planning Birmingham 22 Professionalism Tuscaloosa Birmingham ϭϬ dĂŬŝŶŐĂŶĚĞĨĞŶĚŝŶŐĞƉŽƐŝƟŽŶƐ FEBRUARY 11 Tort Law Update Birmingham 19 Banking Law Birmingham ϭϲ ƵƐŝŶĞƐƐĂŶĚŽŵƉůĞdž>ŝƟŐĂƟŽŶBirmingham 26 Elder Law Birmingham 17 Employment Law Birmingham MAY 6-7 City & County Government 18 Alabama Update Birmingham Orange Beach 21 Trial Skills Birmingham 13 Professionalism Tuscaloosa Keep Your Library Updated with CHECK OUT OTHER Our BEST SELLING PUBLICATIONS KWWKZdhE/d/^&KZ YEAR-END CLE DĐůƌŽLJ͛ƐůĂďĂŵĂǀŝĚĞŶĐĞŝƐƚŚĞĐŽŵƉůĞƚĞĂŶĚĮŶĂůĂƵƚŚŽƌŝƚLJ regarding Alabama evidence issues for judges and lawyers alike. dŚĞŶĞǁ^ƵƉƉůĞŵĞŶƚǁŝůůďĞĂǀĂŝůĂďůĞŝŶĞĂƌůLJϮϬϭϲ͘WƌĞͲŽƌĚĞƌ tĞďĐĂƐƚƐ͗ Most of our live LJŽƵƌĐŽƉLJŶŽǁ͊ seminars will be -

2018 Baptist Health Foundation Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT Thank you for YOUR COMMUNITY Dear Friends of Mississippi Baptist Medical Center, On behalf of our patients, their families, and friends, thank you for the many generous gifts you shared with Baptist Health Foundation in 2018. Because you chose to invest in us, you have Crisler Boone made an impact on the lives of those who benefit from our Executive Director Christian healing ministry. In 2018, the Baptist Health Foundation provided much-needed 4 TRIPLETS! equipment to the hospital. Your generous gifts to our Foundation Mom Says Choosing enabled us to help the tiniest of our patients by providing Baptist Among Her bassinets, Bili-Beds (special beds used to treat infants with “Best” Decisions jaundice), and infant warmers for our well baby and neonatal ICU 5 TRAVIS DUNLAP areas. We continued our support of the Emergency Department Grateful – After Three by providing wheelchairs and beds. We funded equipment in the Close Calls area of respiratory care and cardiovascular care and purchased a 6 MARILYN TURNER leading-edge Arctic Sun® cooling device that can save the lives Lymphedema Patient of our patients who have had a stroke or heart attack. Finds Great Care and Mississippi Baptist Medical Center continues to receive Support recognition for our excellent service and care. In 2018, two of 7 BILLIE AND OSLER MOORE – our specialty areas were named by Healthgrades, America’s Giving and Receiving leading independent healthcare ratings organization, as one of 8 JEFF FINCH America’s 100 Best Hospitals for Joint Replacement Surgery and Cyclist, Turned Cancer Prostate Surgery. The Healthgrades designation for America’s Patient, Rides with a 100 Best Hospitals represents the top 2% of hospitals nationwide. -

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW Albertsons/Safeway Case Study

MERGER ANTITRUST LAW Albertsons/Safeway Case Study Fall 2020 Georgetown University Law Center Professor Dale Collins ALBERTSONS/SAFEWAY CASE STUDY Table of Contents The deal Safeway Inc. and AB Albertsons LLC, Press Release, Safeway and Albertsons Announce Definitive Merger Agreement (Mar. 6, 2014) .............. 4 The FTC settlement Fed. Trade Comm’n, FTC Requires Albertsons and Safeway to Sell 168 Stores as a Condition of Merger (Jan. 27, 2015) .................................... 11 Complaint, In re Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., No. C-4504 (F.T.C. filed Jan. 27, 2015) (challenging Albertsons/Safeway) .................... 13 Agreement Containing Consent Order (Jan. 27, 2015) ................................. 24 Decision and Order (Jan. 27, 2015) (redacted public version) ...................... 32 Order To Maintain Assets (Jan. 27, 2015) (redacted public version) ............ 49 Analysis of Agreement Containing Consent Orders To Aid Public Comment (Nov. 15, 2012) ........................................................... 56 The Washington state settlement Complaint, Washington v. Cerberus Institutional Partners V, L.P., No. 2:15-cv-00147 (W.D. Wash. filed Jan. 30, 2015) ................................... 69 Agreed Motion for Endorsement of Consent Decree (Jan. 30, 2015) ........... 81 [Proposed] Consent Decree (Jan. 30, 2015) ............................................ 84 Exhibit A. FTC Order to Maintain Assets (omitted) ............................. 100 Exhibit B. FTC Order and Decision (omitted) ..................................... -

Consolidation in Food Retailing: Prospects for Consumers & Grocery Suppliers

18 Economic Research Service/USDA Agricultural Outlook/August 2000 Special Article Consolidation in Food Retailing: Prospects for Consumers & Grocery Suppliers n recent years, the U.S. food retailing industry has undergone unprecedented consolidation and structural change through Imergers, acquisitions, divestitures, internal growth, and new competitors. Since 1996, almost 3,500 supermarkets have been purchased, representing annual grocery store sales of more than $67 billion (including food and non-food sales by supermarkets, superettes, and convenience stores). Two of the largest food retailing combinations in history were announced in 1998: the merger of Albertson’s (the nation’s fourth-largest food retailer) with American Stores (the second-largest), and the acquisition of sixth-largest Fred Meyer by first-ranked Kroger Company. The recent consolidation wave has brought together food retail- ers operating within and across regions. While many food retail- ers operate in multiple regions, none is considered truly nation- wide in scope. Of the consolidations, the Albertson’s-American Stores merger, which resulted in common ownership of super- markets reaching coast to coast (but not all regions), comes clos- est to creating a nationwide food retailer. Harrison Jack Widespread consolidation in the grocery industry—driven by The share of consumers’ income spent for food-at-home, pur- expected efficiency gains from economies of size—has had a chased from foodstores and other retail outlets, continued to fall. significant effect on the share of total grocery store sales From 1992 to 1998, the share of disposable income devoted to accounted for by the largest food retailers. It also raises ques- food-at-home fell from 7.8 percent to 7.6 percent, continuing a tions about long-term trends driving these changes and the impli- long-term trend. -

Houchens Industries Jimmie Gipson 493 2.6E Bowling Green, Ky

SN TOP 75 SN TOP 75 2010 North American Food Retailers A=actual sales; E=estimated sales CORPORATE/ SALES IN $ BILLIONS; RANK COMPANY TOP EXECUTIVE(S) FRancHise STORes DATE FISCAL YEAR ENDS 1 Wal-Mart Stores MIKE DUKE 4,624 262.0E Bentonville, Ark. president, CEO 1/31/10 Volume total represents combined sales of Wal-Mart Supercenters, Wal-Mart discount stores, Sam’s Clubs, Neighborhood Markets and Marketside stores in the U.S. and Canada, which account for approximately 64% of total corporate sales (estimated at $409.4 billion in 2009). Wal-Mart operates 2,746 supercenters in the U.S. and 75 in Canada; 152 Neighborhood Markets and four Marketside stores in the U.S.; 803 discount stores in the U.S. and 239 in Canada; and 605 Sam’s Clubs in the U.S. (The six Sam’s Clubs in Canada closed last year, and 10 more Sam’s are scheduled to close in 2010.) 2 Kroger Co. DAVID B. DILLON 3,634 76.0E Cincinnati chairman, CEO 1/30/10 Kroger’s store base includes 2,469 supermarkets and multi-department stores; 773 convenience stores; and 392 fine jewelry stores. Sales from convenience stores account for approximately 5% of total volume, and sales from fine jewelry stores account for less than 1% of total volume. The company’s 850 supermarket fuel centers are no longer included in the store count. 3 Costco Wholesale Corp. JIM SINEGAL 527 71.4A Issaquah, Wash. president, CEO 8/30/09 Revenues at Costco include sales of $69.9 billion and membership fees of $1.5 billion.