Incidence of Aflatoxin in Peanuts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implications for Peanut Allergy

M PO RU LO IA N T O N R E U Acta Sci. Pol., Technol. Aliment. 13(3) 2014, 321-333 I M C S ACTA pISSN 1644-0730 eISSN 1889-9594 www.food.actapol.net/ CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PEANUT CHAIN IN EUROPE – IMPLICATIONS FOR PEANUT ALLERGY Anna M. Prusak1, Małgorzata Schlegel-Zawadzka2, Annabelle Boulay3, Gene Rowe4 1Department of Clinical Nursing, Institute of Nursing and Obstetrics, Jagiellonian University Medical College Kopernika 25, 31-501 Kraków, Poland 2Department of Human Nutrition, Institute of Public Health, Jagiellonian University Medical College Grzegórzecka 20, 31-531 Kraków, Poland 3Geography, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter Amory Building, Rennes Drive, Exeter EX4 4RJ, United Kingdom 4Gene Rowe Evaluation, 12 Wellington Road, Norwich NR2 3HT, United Kingdom ABSTRACT Background. Peanuts are one of the main food allergens, occasionally responsible for life-threatening reac- tions. Thus, many studies have tried to fi nd a connection between peanut allergy prevalence and processes in the peanut chain that may contribute to the peanut allergenicity. To inform this discussion, this paper outlines experiences in peanut cultivation, trade and processing in Europe, focusing on four European countries with different peanut experiences (Poland, Bulgaria, Spain and the UK). Material and method. Results here are based on documentary analysis and semi-structured, face-to-face interviews with 32 experts involved in various stages of the peanut chain, including peanut farmers, proces- sors, traders, food technologists and manufacturers. Results. A common peanut chain diagram has been drawn considering shelled and in-shell peanuts. The analysis of each stage of peanut processing has been made in accordance with this peanut chain schema. -

Peanut and Tree Nut Allergy

In partnership with Primary Children’s Hospital Peanut and Tree Nut Allergy What is a peanut or tree nut allergy? Your child may need to avoid products that could A peanut allergy is an immune reaction to proteins have a high risk for cross-contamination. For this in peanuts. A tree nut allergy is an immune reaction reason your child may need to avoid all peanuts and to proteins in various tree nuts. Some children may tree nuts. be allergic to only certain types of tree nuts. Some Cross-reactivity can also occur. This is when the children may be allergic to both peanuts and various proteins in one food are similar to those in another. types of tree nuts. The immune system sees them as the same and can Some common symptoms of allergy reactions include: cause an allergic reaction. Your child’s doctor will best be able to tell you your child’s risk for cross-reactivity Skin: reactions. They can tell you whether or not to avoid • itchy red rash • flushing additional foods that may cause those reactions. • hives • swelling of face What do I look for when I read the • eczema food labels? Digestive system: 1 Labels on food, that are regulated by the FDA, • belly pain • severe nausea have to say if the food contains the 8 most • blood or mucous in • cramping common food allergens: milk, egg, soy, wheat, stools • itching or swelling of peanuts, tree nuts, shellfish, or fish. Always read • severe diarrhea the lips, mouth, tongue the ingredient list to be sure and check all food • vomiting or throat. -

Earn Money Week in and Week out with a Flea Market Business You Can Run in Just a Few Hours a Week!"

Flea Market Secrets Exposed "Earn Money Week in and Week Out With a Flea Market Business You Can Run in Just a Few Hours a Week!" Written By Wayne & Marggi Stanila: Published By Wayne Stanila: All Rights Reserved: Copyright: © 2010 No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the written permission of the authors. Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to make this document as complete and accurate as possible. However, there may be mistakes in the typography or content. Also, this report contains the flea market and shopping using coupons information up to the publishing date. Therfore, this document should be used as a guide only- not as a definitive source of flea markets or shopping using coupons. The purpose of this document is to educate, and not to provide or imply such provisions of any legal, accounting, or any other form of business advice. The authors and publisher do not warrant that the information contained in this report is fully complete and shall not be responsible for any errors or omissions. The authors and publisher shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directley or indirectley by this document: CONTENTS: CHAPTER ONE: Peanuts, Coupons And Fleas CHAPTER TWO: What You Need To Get Started CHAPTER THREE Green Or Jumbo CHAPTER FOUR Step By Step Cooking CHAPTER FIVE The Set Up CHAPTER SIX How Much To Charge And What To Serve Them In CHAPTER SEVEN Pistachios And Roasted Peanuts CHAPTER EIGHT -

Table of Contents

1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Peanuts — A Brief History 4 Peanut Types and Production 6 U.S. Peanut Supply 7 Export Peanut Market 8 Growing and Harvesting 9 Shelling and Grading 10 U.S. Peanut Grade Chart 12 Custom Products and Processing 14 Standards for U.S. Peanuts Peanuts A Brief History The peanut, while grown in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world, is native to the Western Hemisphere. It originated in South America and spread throughout the New World as Spanish explorers discovered the peanut’s versatility. When the Spaniards returned to Europe, peanuts went with them. Later, traders were responsible for spreading peanuts to Asia and Africa. The peanut made its way back to North America on sailing ships in the 1700s. Although there were some commercial peanut farms in the U.S. during the 1700s and 1800s, peanuts were not grown extensively. This lack of interest in peanut farming is attributed to the fact that the peanut was regarded as food for the poor and because growing and harvesting techniques were slow and difficult. Until the Civil War, the peanut basically remained a regional food associated with the southern United States. After the Civil War, the demand for peanuts increased rapidly. By the end of the 19th century, the development of equipment for production, harvesting and shelling peanuts, as well as processing techniques, contributed to the expansion of the peanut industry. The new 20th century labor-saving equipment resulted in a rising demand for peanut oil, roasted and salted peanuts, peanut butter and confections. 300 Uses Also associated with the expansion of the peanut industry is the research conducted by Dr. -

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions by Ned Hémard

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard Goober Peas Most Southerners recognize the terms goober and goober pea as other names for the peanut. Also known as earthnuts, groundnuts, monkey nuts, pygmy nuts and pig nuts, the peanut (Arachis hypogaea) is a species in the “legume” family (Fabaceae), the third largest family of flowering plants. Of all the “legumes”, the peanut is especially fascinating because it develops below the ground. And like the tomato and the potato, the cultivated peanut was probably first domesticated in Peru. By the time Columbus reached the New World, it was being grown throughout the warmer regions of the Americas. Soon the peanut was introduced into Africa and Asian countries where it became an important ingredient in their local dishes. Brought to China by Portuguese traders in the 17th century, the peanut is widely used in Southeast Asian cuisine (particularly that of Thailand and Indonesia). This delicious “legume” came to Indonesia from the Philippines, where it arrived from Mexico in times of Spanish colonization. What would satay be without its delicious peanut- based sauce? The peanut root system contains nitrogen-fixing bacteria that convert inert atmospheric nitrogen into ammonia. Other bacteria convert the ammonia into nitrites that enrich the soil. George Washington Carver was one of many USDA researchers who knew this and encouraged Southern cotton farmers in the South to grow peanuts instead of, or in addition to, cotton, because cotton had depleted so much nitrogen from the soil. He is often credited with inventing 300 different uses for peanuts (which did not include peanut butter but did include salted peanuts). -

Georgia Peanut Bank Week 37Th

GEOR GIA PEANUT BANK WEEK OCTOBER S M T W T F S 37th 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 28 30 31 Date Oct. 14-18, 2013 ay to the 000 000 000 P Order of Georgia Peanut Bank Week $2, , , no Two billion & /100 DOLLARS GEORGIA PEANUT FOR Peanuts! COMMISSION Georgia Peanut Commission The Right Combination BANK ON PEANUTS BANK ON PEANUTS—from the security that the peanut farm dollar provides the peanut belt’s economy to the nutritional value that benefits the world every day. Cultivate Your Campaign The final mailing that you receive will include the items that you have purchased. Treat your customers to a taste of the South by providing sample peanuts and a lasting impression with lapel pins! Contact local media (newspapers, radio stations, TV stations, etc.) to spread the word! Have them host a broadcast or develop a story on-site. Visit our website (www.gapeanuts.com) for additional recipes, information, and more. Bet Your Bottom Dollar: Ideas That Work! Door prize drawings bring multitudes of new opportunities to market to customers! Develop personalized products that promote your financial institution (piggy banks, stress balls, tape measures, etc.) Boiled or fried peanuts are always a crowd pleaser! Bring in a new customer base, as well as your loyal customers, by providing these delicious and nutritious items to promote your institution. Your County Extension Coordinator is always a good source of information as to the peanut production in your county. -

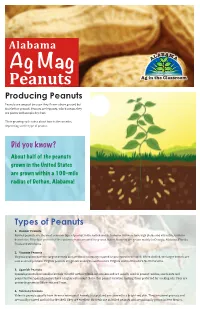

Peanuts Producing Peanuts

Alabama Ag Mag Peanuts Producing Peanuts Peanuts are unusual because they �lower above ground but fruit below ground. Peanuts are legumes, which means they are plants with simple dry fruit. Their growing cycle takes about four to �ive months, depending on the type of peanut. Did you know? About half of the peanuts grown in the United States are grown within a 100-mile radius of Dothan, Alabama! Types of Peanuts 1. Runner Peanuts Runner peanuts are the most common type of peanut in the nation and in Alabama. Runners have high yields and attractive, uniform kernel size. Fifty-four percent of the runners grown are used for peanut butter. Runners are grown mainly in Georgia, Alabama, Florida, Texas and Oklahoma. 2. Virginia Peanuts Virginia peanuts have the largest kernels and are most commonly roasted or processed in the shell. When shelled, the larger kernels are sold as snack peanuts. Virginia peanuts are grown mainly in southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. 3. Spanish Peanuts Spanish peanuts have smaller kernels covered with a reddish-brown skin and are usually used in peanut candies, snack nuts and peanut butter. Spanish peanuts have a higher oil content than other peanut varieties, making them preferred for cooking oils. They are primarily grown in Oklahoma and Texas. 4. Valencia Peanuts Valencia peanuts usually have three or more small kernels to a pod and are covered in a bright-red skin. They are sweet peanuts and are usually roasted and sold in the shell. They are excellent for fresh use as boiled peanuts and are primarily grown in New Mexico. -

March 23, 2017 – National Peanut and National Nutrition Month

DATE: March 23, 2017 MARCH IS….. NATIONAL PEANUT AND NUTRITION MONTH March is a month filled with many food events and activities. Besides being National Nutrition Month, March is also National Peanut Month. National Peanut Month had its beginnings as National Peanut Week in 1941. It was expanded to a month-long celebration in 1974. The peanut (Arachis hypogaea) is actually not really a nut - it is a legume, the same family as beans and peas. There are six cities in the U.S. named Peanut: Peanut, California; Lower Peanut, Pennsylvania; Upper Peanut, Pennsylvania; Peanut, Pennsylvania, Peanut, Tennessee; and Peanut, West Virginia. Boiled Peanuts were designated as the Official Snack Food of South Carolina in 2006. Peanuts originated in South America, where they were cultivated by Indians for at least 2000 years. As early as 1500 B.C., the Incans used peanuts as sacrificial offerings and entombed them with their mummies to aid in the spirit life. Spaniards and Portuguese slave traders introduced them to Africa and Europe, and slaves introduced them to the American South. Though there are several varieties of peanut, the two most popular are the Virginia and the Spanish peanut. The Virginia peanut is larger and more oval in shape than the smaller, rounder Spanish peanut. Unshelled peanuts should have clean, unbroken shells and should not rattle when shaken. Dr. George Washington Carver researched and developed more than 300 uses for peanuts in the early 1900s; Dr. Carver is considered "The Father of the Peanut Industry" because of his extensive research and selfless dedication to promoting peanut production and products. -

Land Views Volume 12

' ' Gardens for the Greater Good The Re-Emergenceof the VictoryGarden &re.at1Aields from:Y 1'-oflerds BARNYARD BASICS ,r-,ii!lh• l'er'IOno'"01m ,r- TALESnoM THEPEANUT GAJ_LER't .......... 1 The View From Here View From Here Our frst issue in a few years brings a picture of good times still to come. ........3 LandViews I is published for stockholders, directors and friends of Farm Credit of Northwest Florida PRESIDENT & CEO The Landing Zone Rick Bitner BOARD OF DIRECTORS Great Yields From No Fields Richard Terry, Chairman No room for a full-fedged garden where you live? Container Melvin Adams, Vice Chairman gardening is a great way to grow your own produce in small spaces. ........ James G Ditty 4 Fred Beshears Tales From The Peanut Gallery Cindy Eade From a largely ignored food item to a staple of the American M Copeland Griswold James Marshall diet, learn how innovations by George Washington Carver and T Butler Walker simple practicality ignited the popularity of this legume. .........8 Robert A Calvert (Outside Director) James R Dean (Outside Director) D Mark Fletcher (Outside Director) Greener Acres EDITOR–IN–CHIEF/MARKETING MANAGER Lesia Andrews Country Miles of Produce Aisles ASSISTANT EDITOR/MARKETING SPECIALIST U-pick farms are wonderful options for fresh produce. What does Debbie Shuler Iit take to start one of your own?.......................................................................................11 PUBLISHER Perpetual Harvest Southern Solutions, Inc Get long-term use out of your fruits, vegetables and herbs PUBLISHING EDITOR utilizing these time-tested preservation techniques. ..................13 Mary Donovan McClellan CREATIVE DIRECTOR/DESIGNER Wild Things Philip Sasser PRINTER Critter Control Wells Printing Company Pesky critters? Put away that toxic pesticide. -

In 1500 B.C., Incans Used Peanuts As Sacrificial Offerings, to Aid in The

In 1500 B.C., Incans Used Peanuts As Sacrificial Offerings, To Aid In The Spirit Life. On September 13 National Peanut Day pays homage to mighty and tasty peanut. Likely originating in South America around 3,500 years ago, this legume is not a nut. They grow underground like potatoes. Since they are an edible seed that forms in a pod, they belong to the family Leguminosae with peas and beans. For the longest time, livestock gained the greatest benefit from all these nutrients. Until modern methods came along, planting and harvesting peanuts were a labor intensive and risky endeavors for farmers.Gradually their popularity grew. From Civil War soldiers who found a fondness for them to PT Barnum’s traveling circus. But what made it possible for peanuts to be grown in abundance was an advancement in farm technology. Just like the cotton gin revolutionized the cotton industry, planters and harvesters transformed not only the peanut farm but farming the world over. Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack ~ lyric from Take Me Out to the Ballgame (1908) by Jack Norworth and Albert Von Tilzer. When the boll weevil wreaked havoc on the South’s cotton crop, Dr. George Washington Carver, who had already been researching this amazing groundnut, suggested farmers diversify into peanuts. It was an economic boon to Southern farmers. He published his research “How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption” in 1916. His continued research resulted in more than delicious uses for this goober, groundnut or ground pea. From shaving cream to plastics and cosmetics and even coffee, Dr. -

Price Discovery and Integration in U.S. Peanut Markets

Journal of Food Distribution Research Volume 51, Issue 1, pp. 78–90 Price Discovery and Integration in U.S. Peanut Markets Hannah Hawkinsa and Senarath Dharmasenabi aUndergraduate Honors Student, Department of Agricultural Economics, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA bAssistant Professor, Department of Agricultural Economics, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, USA Abstract The United States is a major supplier in the world peanut market. Using grower-level monthly peanut price data from 1982 to 2018, we estimate market integration and price discovery patterns at the grower level by applying causality structures identified through machine-learning algorithms. Preliminary analysis shows that Georgia is a price leader and others are followers in current and lag time. Peanut prices in Texas and Georgia are important determinants of prices in other markets such as North Carolina, Virginia, and Alabama. Findings from this study are useful for peanut producers, marketers, and policy makers designing peanut marketing programs. Keywords: directed acyclic graphs, machine learning, market integration, peanut prices, price discovery iCorresponding author: Tel: (979) 862-2894 Email: [email protected] March 2020 78 Volume 51, Issue 1 Hawkins and Dharmasena Journal of Food Distribution Research Introduction The United States is a significant supplier in the world peanut market.1 In the United States, 99% of peanuts are grown in ten states. Georgia grows about 50% of U.S. peanuts, followed by Texas (10%), Alabama (10%), Florida (9%), South and North Carolina (14%), Mississippi, Virginia, New Mexico, and Oklahoma (American Peanut Council, 2018). According to the National Agricultural Statistical Service (NASS) of the U.S. -

Establishment of Peanut Butter Manufacturing Unit

Establishment of Peanut Butter Manufacturing Unit Agro and Food Processing Government of Gujarat Contents Project Concept 3 Market Potential 4 Growth Drivers 8 Gujarat – Competitive Advantage 9 Project Information 11 - Location/ Size - Infrastructure Availability/ Connectivity - Raw Material/ Manpower - Key Players/ Machinery Suppliers - Potential collaboration opportunities - Key Considerations Project Financials 15 Approvals & Incentives 16 Key Department Contacts 18 Page 2 Project Concept Peanut and peanut butter – Overview M Peanut, also known as groundnut, is classified as both a grain legume and an oil crop (because of its high oil content) M The two major varieties of peanuts produced in India are Bold (Virginia) and Java (Spanish) types. The Bold variety peanuts are typically red skinned with elongated shape. The Java variety peanuts are pink skinned with round spheroid shape M Applications: peanuts are used for M Production of nutritional supplements M Peanut butter M Confectionery products – peanut candy bars, peanut butter cookies, cakes, chocolates M Snacking products – salted peanuts, dry-roasted peanuts, boiled peanuts M Peanut butter is a high protein, low calorie product that possess high nutritional value. It is healthy alternative to dairy butter and used popularly in western countries as a spread. M A serving of peanut butter provides many essential vitamins and minerals, including vitamin E, niacin, magnesium, copper, folate, manganese, and phosphorus. It also contains many bioactive compounds such as resveratrol. M Peanut butter are also available in powder form and used in various applications such as breakfast food, savoury sauces and smoothies. M On the basis of product type peanut butter market is divided into regular, low sodium, low sugar and natural.