MIPS® Architecture for Programmers Volume III: MIPS64® / Micromips64

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtual Memory

Chapter 4 Virtual Memory Linux processes execute in a virtual environment that makes it appear as if each process had the entire address space of the CPU available to itself. This virtual address space extends from address 0 all the way to the maximum address. On a 32-bit platform, such as IA-32, the maximum address is 232 − 1or0xffffffff. On a 64-bit platform, such as IA-64, this is 264 − 1or0xffffffffffffffff. While it is obviously convenient for a process to be able to access such a huge ad- dress space, there are really three distinct, but equally important, reasons for using virtual memory. 1. Resource virtualization. On a system with virtual memory, a process does not have to concern itself with the details of how much physical memory is available or which physical memory locations are already in use by some other process. In other words, virtual memory takes a limited physical resource (physical memory) and turns it into an infinite, or at least an abundant, resource (virtual memory). 2. Information isolation. Because each process runs in its own address space, it is not possible for one process to read data that belongs to another process. This improves security because it reduces the risk of one process being able to spy on another pro- cess and, e.g., steal a password. 3. Fault isolation. Processes with their own virtual address spaces cannot overwrite each other’s memory. This greatly reduces the risk of a failure in one process trig- gering a failure in another process. That is, when a process crashes, the problem is generally limited to that process alone and does not cause the entire machine to go down. -

Security and Performance Analysis of Custom Memory Allocators Tiffany

Security and Performance Analysis of Custom Memory Allocators by Tiffany Tang Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2019 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2019. All rights reserved. Author.............................................................. Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science June 10, 2019 Certified by. Howard E. Shrobe Principal Research Scientist and Associate Director of Security, CSAIL Thesis Supervisor Certified by. Hamed Okhravi Senior Technical Staff, MIT Lincoln Laboratory Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Katrina LaCurts, Chair, Masters of Engineering Thesis Committee 2 DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release. Distribution is unlimited. This material is based upon work supported by the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering under Air Force Contract No. FA8702-15-D-0001. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Assistant Secre- tary of Defense for Research and Engineering. 3 Security and Performance Analysis of Custom Memory Allocators by Tiffany Tang Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science on June 10, 2019, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science Abstract Computer programmers use custom memory allocators as an alternative to built- in or general-purpose memory allocators with the intent to improve performance and minimize human error. However, it is difficult to achieve both memory safety and performance gains on custom memory allocators. -

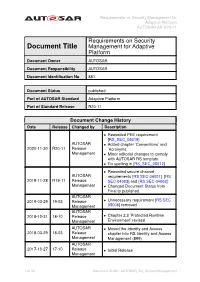

Requirements on Security Management for Adaptive Platform AUTOSAR AP R20-11

Requirements on Security Management for Adaptive Platform AUTOSAR AP R20-11 Requirements on Security Document Title Management for Adaptive Platform Document Owner AUTOSAR Document Responsibility AUTOSAR Document Identification No 881 Document Status published Part of AUTOSAR Standard Adaptive Platform Part of Standard Release R20-11 Document Change History Date Release Changed by Description • Reworded PEE requirement [RS_SEC_05019] AUTOSAR • Added chapter ’Conventions’ and 2020-11-30 R20-11 Release ’Acronyms’ Management • Minor editorial changes to comply with AUTOSAR RS template • Fix spelling in [RS_SEC_05012] • Reworded secure channel AUTOSAR requirements [RS SEC 04001], [RS 2019-11-28 R19-11 Release SEC 04003] and [RS SEC 04003] Management • Changed Document Status from Final to published AUTOSAR 2019-03-29 19-03 Release • Unnecessary requirement [RS SEC Management 05006] removed AUTOSAR 2018-10-31 18-10 Release • Chapter 2.3 ’Protected Runtime Management Environment’ revised AUTOSAR • Moved the Identity and Access 2018-03-29 18-03 Release chapter into RS Identity and Access Management Management (899) AUTOSAR 2017-10-27 17-10 Release • Initial Release Management 1 of 32 Document ID 881: AUTOSAR_RS_SecurityManagement Requirements on Security Management for Adaptive Platform AUTOSAR AP R20-11 Disclaimer This work (specification and/or software implementation) and the material contained in it, as released by AUTOSAR, is for the purpose of information only. AUTOSAR and the companies that have contributed to it shall not be liable for any use of the work. The material contained in this work is protected by copyright and other types of intel- lectual property rights. The commercial exploitation of the material contained in this work requires a license to such intellectual property rights. -

CSE421 Midterm Solutions —SOLUTION SET— 09 Mar 2012

CSE421 Midterm Solutions —SOLUTION SET— 09 Mar 2012 This midterm exam consists of three types of questions: 1. 10 multiple choice questions worth 1 point each. These are drawn directly from lecture slides and intended to be easy. 2. 6 short answer questions worth 5 points each. You can answer as many as you want, but we will give you credit for your best four answers for a total of up to 20 points. You should be able to answer the short answer questions in four or five sentences. 3. 2 long answer questions worth 20 points each. Please answer only one long answer question. If you answer both, we will only grade one. Your answer to the long answer should span a page or two. Please answer each question as clearly and succinctly as possible. Feel free to draw pic- tures or diagrams if they help you to do so. No aids of any kind are permitted. The point value assigned to each question is intended to suggest how to allocate your time. So you should work on a 5 point question for roughly 5 minutes. CSE421 Midterm Solutions 09 Mar 2012 Multiple Choice 1. (10 points) Answer all ten of the following questions. Each is worth one point. (a) In the story that GWA (Geoff) began class with on Monday, March 4th, why was the Harvard student concerned about his grade? p He never attended class. He never arrived at class on time. He usually fell asleep in class. He was using drugs. (b) All of the following are inter-process (IPC) communication mechanisms except p shared files. -

Paging: Smaller Tables

20 Paging: Smaller Tables We now tackle the second problem that paging introduces: page tables are too big and thus consume too much memory. Let’s start out with a linear page table. As you might recall1, linear page tables get pretty 32 12 big. Assume again a 32-bit address space (2 bytes), with 4KB (2 byte) pages and a 4-byte page-table entry. An address space thus has roughly 232 one million virtual pages in it ( 212 ); multiply by the page-table entry size and you see that our page table is 4MB in size. Recall also: we usually have one page table for every process in the system! With a hundred active processes (not uncommon on a modern system), we will be allocating hundreds of megabytes of memory just for page tables! As a result, we are in search of some techniques to reduce this heavy burden. There are a lot of them, so let’s get going. But not before our crux: CRUX: HOW TO MAKE PAGE TABLES SMALLER? Simple array-based page tables (usually called linear page tables) are too big, taking up far too much memory on typical systems. How can we make page tables smaller? What are the key ideas? What inefficiencies arise as a result of these new data structures? 20.1 Simple Solution: Bigger Pages We could reduce the size of the page table in one simple way: use bigger pages. Take our 32-bit address space again, but this time assume 16KB pages. We would thus have an 18-bit VPN plus a 14-bit offset. -

Virtual Memory Basics

Operating Systems Virtual Memory Basics Peter Lipp, Daniel Gruss 2021-03-04 Table of contents 1. Address Translation First Idea: Base and Bound Segmentation Simple Paging Multi-level Paging 2. Address Translation on x86 processors Address Translation pointers point to objects etc. transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data enables number of advanced features programmers perspective: Address Translation OS in control of address translation pointers point to objects etc. transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data programmers perspective: Address Translation OS in control of address translation enables number of advanced features pointers point to objects etc. transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data Address Translation OS in control of address translation enables number of advanced features programmers perspective: transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data Address Translation OS in control of address translation enables number of advanced features programmers perspective: pointers point to objects etc. Address Translation OS in control of address translation enables number of advanced features programmers perspective: pointers point to objects etc. transparent: it is not necessary to know how memory reference is converted to data Address Translation - Idea / Overview Shared libraries, interprocess communication Multiple regions for dynamic allocation -

Virtual Memory - Paging

Virtual memory - Paging Johan Montelius KTH 2020 1 / 32 The process code heap (.text) data stack kernel 0x00000000 0xC0000000 0xffffffff Memory layout for a 32-bit Linux process 2 / 32 Segments - a could be solution Processes in virtual space Address translation by MMU (base and bounds) Physical memory 3 / 32 one problem Physical memory External fragmentation: free areas of free space that is hard to utilize. Solution: allocate larger segments ... internal fragmentation. 4 / 32 another problem virtual space used code We’re reserving physical memory that is not used. physical memory not used? 5 / 32 Let’s try again It’s easier to handle fixed size memory blocks. Can we map a process virtual space to a set of equal size blocks? An address is interpreted as a virtual page number (VPN) and an offset. 6 / 32 Remember the segmented MMU MMU exception no virtual addr. offset yes // < within bounds index + physical address segment table 7 / 32 The paging MMU MMU exception virtual addr. offset // VPN available ? + physical address page table 8 / 32 the MMU exception exception virtual address within bounds page available Segmentation Paging linear address physical address 9 / 32 a note on the x86 architecture The x86-32 architecture supports both segmentation and paging. A virtual address is translated to a linear address using a segmentation table. The linear address is then translated to a physical address by paging. Linux and Windows do not use use segmentation to separate code, data nor stack. The x86-64 (the 64-bit version of the x86 architecture) has dropped many features for segmentation. -

Virtual Memory in X86

Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 Virtual Memory in x86 Nima Honarmand Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 x86 Processor Modes • Real mode – walks and talks like a really old x86 chip • State at boot • 20-bit address space, direct physical memory access • 1 MB of usable memory • No paging • No user mode; processor has only one protection level • Protected mode – Standard 32-bit x86 mode • Combination of segmentation and paging • Privilege levels (separate user and kernel) • 32-bit virtual address • 32-bit physical address • 36-bit if Physical Address Extension (PAE) feature enabled Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 x86 Processor Modes • Long mode – 64-bit mode (aka amd64, x86_64, etc.) • Very similar to 32-bit mode (protected mode), but bigger address space • 48-bit virtual address space • 52-bit physical address space • Restricted segmentation use • Even more obscure modes we won’t discuss today xv6 uses protected mode w/o PAE (i.e., 32-bit virtual and physical addresses) Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 Virt. & Phys. Addr. Spaces in x86 Processor • Both RAM hand hardware devices (disk, Core NIC, etc.) connected to system bus • Mapped to different parts of the physical Virtual Addr address space by the BIOS MMU Data • You can talk to a device by performing Physical Addr read/write operations on its physical addresses Cache • Devices are free to interpret reads/writes in any way they want (driver knows) System Interconnect (Bus) : all addrs virtual DRAM Network … Disk (Memory) Card : all addrs physical Fall 2017 :: CSE 306 Virt-to-Phys Translation in x86 0xdeadbeef Segmentation 0x0eadbeef Paging 0x6eadbeef Virtual Address Linear Address Physical Address Protected/Long mode only • Segmentation cannot be disabled! • But can be made a no-op (a.k.a. -

Virtual Memory

CSE 410: Systems Programming Virtual Memory Ethan Blanton Department of Computer Science and Engineering University at Buffalo Introduction Address Spaces Paging Summary References Virtual Memory Virtual memory is a mechanism by which a system divorces the address space in programs from the physical layout of memory. Virtual addresses are locations in program address space. Physical addresses are locations in actual hardware RAM. With virtual memory, the two need not be equal. © 2018 Ethan Blanton / CSE 410: Systems Programming Introduction Address Spaces Paging Summary References Process Layout As previously discussed: Every process has unmapped memory near NULL Processes may have access to the entire address space Each process is denied access to the memory used by other processes Some of these statements seem contradictory. Virtual memory is the mechanism by which this is accomplished. Every address in a process’s address space is a virtual address. © 2018 Ethan Blanton / CSE 410: Systems Programming Introduction Address Spaces Paging Summary References Physical Layout The physical layout of hardware RAM may vary significantly from machine to machine or platform to platform. Sometimes certain locations are restricted Devices may appear in the memory address space Different amounts of RAM may be present Historically, programs were aware of these restrictions. Today, virtual memory hides these details. The kernel must still be aware of physical layout. © 2018 Ethan Blanton / CSE 410: Systems Programming Introduction Address Spaces Paging Summary References The Memory Management Unit The Memory Management Unit (MMU) translates addresses. It uses a per-process mapping structure to transform virtual addresses into physical addresses. The MMU is physical hardware between the CPU and the memory bus. -

Virtual Memory

Saint LouisCarnegie University Mellon Virtual Memory CSCI 224 / ECE 317: Computer Architecture Instructor: Prof. Jason Fritts Slides adapted from Bryant & O’Hallaron’s slides 1 Saint LouisCarnegie University Mellon Data Representation in Memory Memory organization within a process Virtual vs. Physical memory ° Fundamental Idea and Purpose ° Page Mapping ° Address Translation ° Per-Process Mapping and Protection 2 Saint LouisCarnegie University Mellon Recall: Basic Memory Organization • • • Byte-Addressable Memory ° Conceptually a very large array, with a unique address for each byte ° Processor width determines address range: ° 32-bit processor has 2 32 unique addresses ° 64-bit processor has 264 unique addresses Where does a given process reside in memory? ° depends upon the perspective… – virtual memory: process can use most any virtual address – physical memory: location controlled by OS 3 Saint LouisCarnegie University Mellon Virtual Address Space not drawn to scale 0xFFFFFFFF for IA32 (x86) Linux Stack 8MB All processes have the same uniform view of memory Stack ° Runtime stack (8MB limit) ° E. g., local variables Heap ° Dynamically allocated storage ° When call malloc() , calloc() , new() Data ° Statically allocated data ° E.g., global variables, arrays, structures, etc. Heap Text Data Text ° Executable machine instructions 0x08000000 ° Read-only data 0x00000000 4 Saint LouisCarnegie University Mellon not drawn to scale Memory Allocation Example 0xFF…F Stack char big_array[1<<24]; /* 16 MB */ char huge_array[1<<28]; /* 256 MB */ int beyond; char *p1, *p2, *p3, *p4; int useless() { return 0; } int main() { p1 = malloc(1 <<28); /* 256 MB */ p2 = malloc(1 << 8); /* 256 B */ p3 = malloc(1 <<28); /* 256 MB */ p4 = malloc(1 << 8); /* 256 B */ /* Some print statements .. -

CS 351: Systems Programming

Virtual Memory CS 351: Systems Programming Michael Saelee <[email protected]> Computer Science Science registers cache (SRAM) main memory (DRAM) local hard disk drive (HDD/SSD) remote storage (networked drive / cloud) previously: SRAM ⇔ DRAM Computer Science Science registers cache (SRAM) main memory (DRAM) local hard disk drive (HDD/SSD) remote storage (networked drive / cloud) next: DRAM ⇔ HDD, SSD, etc. i.e., memory as a “cache” for disk Computer Science Science main goals: 1. maximize memory throughput 2. maximize memory utilization 3. provide address space consistency & memory protection to processes Computer Science Science throughput = # bytes per second - depends on access latencies (DRAM, HDD) and “hit rate” Computer Science Science utilization = fraction of allocated memory that contains “user” data (aka payload) - vs. metadata and other overhead required for memory management Computer Science Science address space consistency → provide a uniform “view” of memory to each process 0xffffffff Computer Science Science Kernel virtual memory Memory (code, data, heap, stack) invisible to 0xc0000000 user code User stack (created at runtime) %esp (stack pointer) Memory mapped region for shared libraries 0x40000000 brk Run-time heap (created by malloc) Read/write segment ( , ) .data .bss Loaded from the Read-only segment executable file (.init, .text, .rodata) 0x08048000 0 Unused address space consistency → provide a uniform “view” of memory to each process Computer Science Science memory protection → prevent processes from directly accessing -

Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture

Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture Andrew Waterman Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences University of California at Berkeley Technical Report No. UCB/EECS-2016-1 http://www.eecs.berkeley.edu/Pubs/TechRpts/2016/EECS-2016-1.html January 3, 2016 Copyright © 2016, by the author(s). All rights reserved. Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. To copy otherwise, to republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission. Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture by Andrew Shell Waterman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor David Patterson, Chair Professor Krste Asanovi´c Associate Professor Per-Olof Persson Spring 2016 Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture Copyright 2016 by Andrew Shell Waterman 1 Abstract Design of the RISC-V Instruction Set Architecture by Andrew Shell Waterman Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science University of California, Berkeley Professor David Patterson, Chair The hardware-software interface, embodied in the instruction set architecture (ISA), is arguably the most important interface in a computer system. Yet, in contrast to nearly all other interfaces in a modern computer system, all commercially popular ISAs are proprietary.