The Origins and Establishment of the Australian Council for International Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineer and Water Commissioner, Was Born on 17 June 1899 At

E EAST, SIR LEWIS RONALD the other commissioner’s health broke down, (RON) (1899–1994), engineer and water leaving East as the sole member. In October commissioner, was born on 17 June 1899 at he was appointed chairman, a position he Auburn, Melbourne, second of three children held until his retirement on 31 January 1965 of Lewis Findlay East, civil servant and later (believed at the time to be the longest tenure as secretary of the Commonwealth Marine head of a government department or authority Branch, and his wife Annie Eleanor, née in Australia). An outstanding engineer, Burchett, both Victorian born. Ronald was inspiring leader, efficient administrator, educated at Ringwood and Tooronga Road and astute political operator, he dominated State schools before winning a scholarship successive water ministers with his forceful to Scotch College, Hawthorn, which he personality and unmatched knowledge of attended from 1913 to 1916, in his final year Victoria’s water issues. He also served as a River winning a government senior scholarship to Murray commissioner (1936–65), in which the University of Melbourne (BEng, 1922; role he exerted great influence on water policy MEng, 1924). throughout south-east Australia. Among many Interrupting his university studies after one examples, he argued successfully for a large year, East enlisted in the Australian Imperial increase in the capacity of the Hume Reservoir. Force on 17 January 1918 for service in World Possibly the most famous photograph used to War I. He arrived in England in May as a 2nd illustrate Australia’s water problems shows East class air mechanic and began flying training in in 1923 literally standing astride the Murray October. -

Support Material for K–6 Human Society and Its Environment Syllabus

Support material for K–6 Human Society and Its Environment Syllabus The New South Wales Department of Education and Training acknowledges the following people and organisations that made contributions to this document. Project adviser Alex Mills, Teacher-librarian retired, Chatham High School Project manager Mike Lembach, HSIE Project Officer, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Reviewers and contributors Ann Arnott Ryde Public School Sheikh Khalil Chami Islamic Council of NSW Barry Corr Drug Education Adviser, Student Services and Equity Programs Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Martin Domench Administration Officer, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Chris Dorbis Civics and Citizenship Officer, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training FOSCO The NSW Federation of School Community Organisations Inc John Gore Chief Education Officer HSIE, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Gloria Habib Community Information Officer, St George District Office, NSW Department of Education and Training Hala Hazel Studies of Asia Coordinator, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Dr George Hazell Director, Heritage Centre, The Salvation Army Reverend Dr Denis Kirkaldy Head Teacher, HSIE, William Carey Christian School Cecilie Knowles Illustrator Suzanne Leslie Teacher-librarian, -

NSW By-Elections 1965-2005

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE New South Wales By-elections, 1965 - 2005 by Antony Green Background Paper No 3/05 ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 0 7313 1786 6 September 2005 The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the New South Wales Parliamentary Library. © 2005 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, with the prior written consent from the Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. New South Wales By-elections, 1965 - 2005 by Antony Green NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE David Clune (MA, PhD, Dip Lib), Manager..............................................(02) 9230 2484 Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government / Law .........................(02) 9230 2356 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ......................(02) 9230 2768 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Research Officer, Law ...................................(02) 9230 3085 Stewart Smith (BSc (Hons), MELGL), Research Officer, Environment ...(02) 9230 2798 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics.......................(02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. Information about Research Publications can be found on the Internet at: http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/WEB_FEED/PHWebContent.nsf/PHPages/LibraryPublications Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. -

~FSHS Distinguished Fortians 18.02.2020 NEW.Rev.Ed MASTER

DISTINGUISHED FORTIANS 20 Name, Achievements Occupation Notes, Sources (see also notes at end) Abbott, Edwin CBE Public servant 1878-1947 • Comptroller General of Customs 1933-1944; CBE 1933 Fortian 1893 Entered NSW Customs Dept. 1893 aged 15 • Chief Inspector in the Federal Public Service Trove.nla.nla.news-article, E Abbott …30 Oct 2016 • Chief Surveyor Central Office Melbourne 1924; then Canberra 1927 Jnr.1893, NSW Jnr Snr Public Exams 1867-1916 online Honours/awards/Edwin Abbott …1 Feb 2019 Fort Street Centenary Book, 1949, p.78 Ada, Gordon Leslie AO, DSc University academic 1922-2012 • Emeritus Professor of Microbiology, John Curtin school of Medical Microbiologist Fortian 1939 Research ANU BSc 1944, MSc 1946, DSc 1961 (all USyd); FAA USyd alumni sidneienses/search • An important contributor to the World Health Organisation 1971-91 Anu.edu.au/news, Prof. Gordon Ada…23 Nov 2016 • Elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science 1964; served as Honours/awards/Gordon L Ada …1 Feb 2019 its Foreign Secretary 1977-81 LC 1939 results • AO for service to medicine in the field of immunology and international health 1993 Adams, Beverlee Jill Louisa (Saul) AM Teacher Fortian 1948 Environment Parks (pdf.p.49)...14 Jul 2017 • Farmer NSW winner of ABC Rural Woman of the Year Award 1995 Honours/awards/Beverlee Adams …1 Feb 2019 • Local Council Member LC 1948 results SMH online; Fortian, 1997, p.6 • Member of Rural Women’s Network, State Advisory Committee • AM for services to local government, the community, conservation 2001 Adams, William Duncan “Bill” BA, BD, D.Min Minister of religion Fortian 1947 • Minister of the Wesley Central Mission, Brisbane BA USyd 1954; BD Melb; D.Min San Francisco; Theol. -

A Dissident Liberal

A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME PETER BAUME Edited by John Wanna and Marija Taflaga A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Baume, Peter, 1935– author. Title: A dissident liberal : the political writings of Peter Baume / Peter Baume ; edited by Marija Taflaga, John Wanna. ISBN: 9781925022544 (paperback) 9781925022551 (ebook) Subjects: Liberal Party of Australia. Politicians--Australia--Biography. Australia--Politics and government--1972–1975. Australia--Politics and government--1976–1990. Other Creators/Contributors: Taflaga, Marija, editor. Wanna, John, editor. Dewey Number: 324.294 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press CONTENTS Foreword . vii Introduction: A Dissident Liberal—A Principled Political Career . xiii 1 . My Dilemma: From Medicine to the Senate . 1 2 . Autumn 1975 . 17 3 . Moving Towards Crisis: The Bleak Winter of 1975 . 25 4 . Budget 1975 . 37 5 . Prelude to Crisis . 43 6 . The Crisis Deepens: October 1975 . 49 7 . Early November 1975 . 63 8 . Remembrance Day . 71 9 . The Election Campaign . 79 10 . Looking Back at the Dismissal . 91 SPEECHES & OTHER PRESENTATIONS Part 1: Personal Philosophies Liberal Beliefs and Civil Liberties (1986) . -

The Making of a Not-So-Accidental Politician Ann Symonds Described

The Making of a Not-so-Accidental Politician Ann Symonds described herself an accidental politician and, when she arrived in the Legislative Council to fill a casual vacancy, some of her Labor colleagues were inclined to agree. Who was this housewife from the affluent Eastern Suburbs of Sydney? Barney French, MLC, heard her fighting ‘maiden’ speech and wondered aloud ‘What would you know about the workers?’1 Ann’s male colleagues soon discovered that she was no privileged newcomer parachuted into a Council seat, but her path to Labor activism had been rather different from their own. A Good Catholic Girl Elizabeth Ann Burley (always known as Ann) was born in Murwillumbah on 12 July 1939. Welcoming a child on ‘the Twelfth’ – the day when Ulster Protestants celebrate the triumphs of William of Orange – was mortifying to her mother, Jean, and the rest of Ann’s Catholic family. Even her father Frank, who ‘had a healthy disrespect for the Church’ was reluctant to inform his parents about the birthday.2 Although some members of the Burley family were active in the Labor party – one of her uncles sponsored Johno Johnson into the local branch – Ann was not one of those children who grew up handing out how-to- vote cards. It was Catholicism rather than Labor politics that shaped her childhood, although the distinction between the two was not so clear-cut in the New South Wales of the 1940s. Ann’s Catholic education – at Mount St Patrick’s Primary, Murwillumbah and later as a boarder at St Mary’s College, Lismore – stimulated her love of music, theatre and the visual arts. -

A History of the Askin Government 1965-1975, Phd Thesis, Loughnan

A History of the Askin Government 1965-1975 Paul E. Loughnan BA [History], MA [History] A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of New England October 2013 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family and good friends; Kate, Anthony, Benjamin Samuel, Thea and Mike. I will always be grateful for their patience, encouragement and unswerving support. And I have no doubt that they were instrumental in the completion of this PhD degree. Acknowledgements The debt to my Principal supervisor Dr Tim Battin is immense. At the beginning of the candidateship the circumstances were such that without his concurrence to take me on I would not have been able to undertake and complete this dissertation. At no time did I ever have any reason to doubt his professionalism and his commitment to the academic process. From my PhD experience this approach is essential and engenders the confidence required to complete such a rigorous project. As a result I still retain the belief that it is a privilege to be a candidate in the University’s PhD degree. I acknowledge my debt to the late Dr Mark Hayne who was my first lecturer at UNE when I began my tertiary education as a mature age student. He rekindled my interest in history and encouraged me to undertake research projects. My good fortune continued when Associate Professor Frank Bongiorno arrived at UNE. His professionalism and dedication to history was inspiring. Frank supervised my Masters dissertation which culminated in my PhD candidateship. He continued his commitment and interest in my pursuits by generously allocating time to this dissertation. -

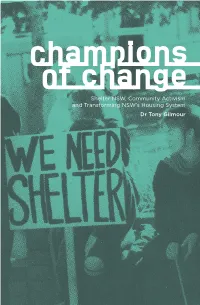

Champions of Change

champions of change Shelter NSW, Community Activism and Transforming NSW’s Housing System Dr Tony Gilmour National Housing Action 1988 champions of change Shelter NSW, Community Activism and Transforming NSW’s Housing System Dr Tony Gilmour First published September 2018 ISBN 978-0-646-99221-1 © Tony Gilmour and Shelter NSW, 2018 Shelter NSW, Level 2, 10 Mallett Street, Camperdown NSW 2050 www.shelternsw.org.au Copyright information This publication was written by Tony Gilmour on behalf of Shelter NSW and its contents are the property of the author and Shelter NSW. This publication may be reproduced in part or whole by non-profit organisations and individuals for educational purposes, as long as Shelter NSW and the author are acknowledged. Any opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Shelter NSW. Cover design: Kim Allen Design ii Champions of Change Contents List of Tables, Figures and Boxes iv Foreword v Introduction ix 1 On Fertile Ground: Shelter’s Origins 1.1 Slum landlords, squalor and workers’ housing 1 1.2 The march of developers, expressways and the Commission 6 1.3 Residents and unions fight back 10 1.4 It’s time: For the Whitlam government 14 2 A Voluntary Organisation: Shelter 1974–84 2.1 Born in 1974, but which Shelter? 21 2.2 The political pendulum swings three times 32 2.3 Shelter comes of age 39 3 Midwife to the Sector: Shelter Supporting the Housing Network 3.1 Birth and flight of the Tenants’ Union 47 3.2 Nurturing an activist housing sector 52 3.3 Community -

Marjorie Oneill Inaugural Speech.Pdf

Legislative Assembly Hansard - 08 May 2019 - Proof Page 1 of 9 Legislative Assembly Hansard – 08 May 2019 – Proof INAUGURAL SPEECHES The DEPUTY SPEAKER: I welcome to the public gallery, friends and family of the member for Coogee. Dr MARJORIE O'NEILL (Coogee) (17:01): I first acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we are gathered: the Gadigal people of the Eora as well as the Bidjigal people who occupy the eastern suburbs coastline and the electorate of Coogee. I pay my respects to them, their elders past, present and emerging. I apologise to all Indigenous Australians for all the harm that has been inflicted upon them by me or any member of my family past or present. I acknowledge that the State of New South Wales has not yet done what needs to be done to acknowledge the injustices inflicted upon our First Nations people. I commit to doing my best to ensure that this Parliament starts treaty or treaties negotiations with our First Nations people. I enter this House standing on the shoulders of giants, from where I can clearly see the purpose of my being here. Giants like Kristina Keneally, who put at the heart of her Government a care for the most vulnerable in the community, particularly people with a disability, a Premier who legalised same-sex adoption, improved emergency department wait times, and properly funded schools and TAFE all the while maintaining a budget surplus during the global financial crisis. I stand on the shoulders of Bob Carr, whomForbes Magazine called "dragon slayer" for his landmark tort law reforms, a Premier who created 350 new national parks, and the first Premier in the State's history to retire debt. -

The Political Writings of Peter Baume

A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME PETER BAUME Edited by John Wanna and Marija Taflaga A DISSIDENT LIBERAL THE POLITICAL WRITINGS OF PETER BAUME Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Baume, Peter, 1935– author. Title: A dissident liberal : the political writings of Peter Baume / Peter Baume ; edited by Marija Taflaga, John Wanna. ISBN: 9781925022544 (paperback) 9781925022551 (ebook) Subjects: Liberal Party of Australia. Politicians--Australia--Biography. Australia--Politics and government--1972–1975. Australia--Politics and government--1976–1990. Other Creators/Contributors: Taflaga, Marija, editor. Wanna, John, editor. Dewey Number: 324.294 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press CONTENTS Foreword . vii Introduction: A Dissident Liberal—A Principled Political Career . xiii 1 . My Dilemma: From Medicine to the Senate . 1 2 . Autumn 1975 . 17 3 . Moving Towards Crisis: The Bleak Winter of 1975 . 25 4 . Budget 1975 . 37 5 . Prelude to Crisis . 43 6 . The Crisis Deepens: October 1975 . 49 7 . Early November 1975 . 63 8 . Remembrance Day . 71 9 . The Election Campaign . 79 10 . Looking Back at the Dismissal . 91 SPEECHES & OTHER PRESENTATIONS Part 1: Personal Philosophies Liberal Beliefs and Civil Liberties (1986) . -

FSHS Distinguished Fortians 2018

DISTINGUISHED FORTIANS 20 Name, Achievements Occupation Notes, Sources (see also notes at end) Abbott, Edwin CBE Public servant 1878-1947 Comptroller General of Customs 1933-1944; CBE 1933 Fortian 1893 Entered NSW Customs Dept. 1893 aged 15 Chief Inspector in the Federal Public Service Trove.nla.nla.news-article, E Abbott …30 Oct 2016 Chief Surveyor Central Office Melbourne 1924; then Canberra 1927 Jnr.1893, NSW Jnr Snr Public Exams 1867-1916 online Honours/awards/Edwin Abbott …1 Feb 2019 Fort Street Centenary Book, 1949, p.78 Ada, Gordon Leslie AO, DSc University academic 1922-2012 Emeritus Professor of Microbiology, John Curtin school of Medical Microbiologist Fortian 1939 Research ANU BSc 1944, MSc 1946, DSc 1961 (all USyd); FAA USyd alumni sidneienses/search An important contributor to the World Health Organisation 1971-91 Anu.edu.au/news, Prof. Gordon Ada…23 Nov 2016 Elected a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science 1964; served as Honours/awards/Gordon L Ada …1 Feb 2019 its Foreign Secretary 1977-81 LC 1939 results AO for service to medicine in the field of immunology and international health 1993 Adams, Beverlee Jill Louisa (Saul) AM Teacher Fortian 1948 Environment Parks (pdf.p.49)...14 Jul 2017 Farmer NSW winner of ABC Rural Woman of the Year Award 1995 Honours/awards/Beverlee Adams …1 Feb 2019 Local Council Member LC 1948 results SMH online; Fortian, 1997, p.6 Member of Rural Women’s Network, State Advisory Committee AM for services to local government, the community, conservation 2001 Adams, William Duncan “Bill” BA, BD, D.Min Minister of religion Fortian 1947 Minister of the Wesley Central Mission, Brisbane BA USyd 1954; BD Melb; D.Min San Francisco; Theol. -

Connecting with the People: the 1978 Reconstitution of the Legislative Council – David Clune

Connecting with the People: The 1978 reconstitution of the Legislative Council – David Clune part two Part Two of the Legislative Council’s Oral History Project President’s foreword It is hard to believe that less than 40 years ago the New South Wales Legislative Council was still not directly elected. Although the pre- 1978 Council did useful work as a traditional house of review, it is almost unrecognisable from the Legislative Council of today, with its wide representation, active committee system, and assertiveness around its powers. The story of precisely how the Council came to be reconstituted in 1978 is fascinating, and indeed essential knowledge for those who wish to fully understand the modern Legislative Council. In this monograph Dr David Clune tells that story, drawing on the memories of some of those who observed and participated in those dramatic events. This is the second monograph arising from the Council’s oral history project. The project commenced in 2013 as part of a series of events to mark the 25th anniversary of the Legislative Council’s modern committee system. I am delighted that the project recommenced in 2015 and look forward to future monographs in the series. I particularly want to thank those former members and clerks who have given so generously of their time to contribute to the project. Most of all I want to thank them for their contributions to the history and development of the extraordinary and unique institution that is the NSW Legislative Council. This is their story. Don Harwin MLC President Preface and Acknowledgements This is the second publication resulting from the Legislative Council’s Oral History Project.* It is based on interviews with former members and staff of the Council.