The Making of a Not-So-Accidental Politician Ann Symonds Described

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 1998/99

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL 1999Annual Report Mission Access to Services To service and enhance the operations of the New South Wales Parliament by providing an apolitical, Located at: Parliament House innovative and integrated support service to support Macquarie Street Members both within and outside Parliament House SYDNEY NSW 2000 and relevant services to the people of New South Wales. Contact telephone & facsimile numbers Corporate Goals Telephone Facsimile Switchboard 9230 2111 Goal 1 Provide the procedural support, advice and Members 9230 2111 Clerks Office 9230 2346 9230 2761 research necessary for the effective functioning Procedure Office 9230 2331 9230 2876 of the House. Committee Office 9230 2641 9230 2812 Administration Office 9230 2824 9230 2876 Goal 2 Provide services which support members in Attendants Reception Desk 9230 2319 9230 2876 their electoral and constituency duties. Goal 3 Provide effective and professional E-mail address: administrative support and services to Members and to other client groups and [email protected] maintain appropriate reporting mechanisms. Goal 4 Provide a safe and healthy working Legislative Councils Home Page on the environment, in which Members and staff can Internet: reach their maximum productivity. http://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/lc Goal 5 Promote public awareness of the purpose, functions and work of the Parliament. Office operating hours Goal 6 Maintain and enhance an appropriate physical The Legislative Council office is open weekdays, environment for the conduct of Parliamentary excluding public holidays, between 9.00 am and 5.00 business while preserving the heritage value pm on non-sitting days, and from 9.00 am until the of Parliament House. -

The Interface Between Aboriginal People and Maori/Pacific Islander Migrants to Australia

CUZZIE BROS: THE INTERFACE BETWEEN ABORIGINAL PEOPLE AND MAORI/PACIFIC ISLANDER MIGRANTS TO AUSTRALIA By James Rimumutu George BA (Hons) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Newcastle March 2014 i This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: Date: ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisors, Professor John Maynard and Emeritus Professor John Ramsland for their input on this thesis. Professor Maynard in particular has been an inspiring source of support throughout this process. I would also like to give my thanks to the Wollotuka Institute of Indigenous Studies. It has been so important to have an Indigenous space in which to work. My special thanks to Dr Lena Rodriguez for having faith in me to finish this thesis and also for her practical support. For my daughter, Mereana Tapuni Rei – Wahine Toa – go girl. I also want to thank all my brothers and sisters (you know who you are). Without you guys life would not have been so interesting growing up. This thesis is dedicated to our Mum and Dad who always had an open door and taught us to be generous and to share whatever we have. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

Hon Penny Sharpe

NSW Legislative Council Hansard Page 1 of 3 NSW Legislative Council Hansard Rice Marketing Amendment (Prevention of National Competition Policy Penalties) Bill Extract from NSW Legislative Council Hansard and Papers Wednesday 16 November 2005. The Hon. PENNY SHARPE [5.43 p.m.] (Inaugural speech): I support the Rice Marketing Authority (Prevention of National Competition Council Penalties) Amendment Bill. As this is my first speech in this place I wish to formally acknowledge that we hold our deliberations on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. I pay my respects to elders past and present and to the Aboriginal people present here today. I thank the members of the House for their courtesy and indulgence as I take this opportunity to talk about the path that has brought me to this place, the values I have gained on the way, and what I hope to achieve as a member of Parliament. I joined the Labor Party when I was 19 for the very simple reason that I wanted to change the world— immediately. It is taking a little longer than I expected. But although I know now that commitment to change must be matched with patience and perseverance, I still believe in the principles and values I held as a young woman at her first Labor Party branch meeting. Australia is a nation of abundant wealth—in our environment, in our people, in our diversity and in our spirit. We are able to care for all of our citizens. That we do not is a burning injustice. I could not and cannot accept that in a wealthy nation like Australia we tolerate the poverty, the violence and the plain unfairness that too many Australians experience day after day. -

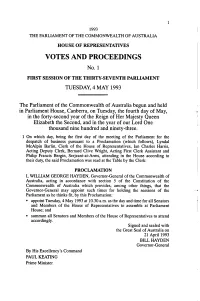

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1993 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 4 MAY 1993 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the fourth day of May, in the forty-second year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and ninety-three. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (which follows), Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Ian Charles Harris, Acting Deputy Clerk, Bernard Clive Wright, Acting First Clerk Assistant and Philip Francis Bergin, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION I, WILLIAM GEORGE HAYDEN, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, acting in accordance with section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia which provides, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, by this Proclamation: " appoint Tuesday, 4 May 1993 at 10.30 a.m. as the day and time for all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to assemble at Parliament House; and * summon all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to attend accordingly. Signed and sealed with the Great Seal of Australia on 21 April 1993 BILL HAYDEN Governor-General By His Excellency's Command PAUL KEATING Prime Minister No. -

Engineer and Water Commissioner, Was Born on 17 June 1899 At

E EAST, SIR LEWIS RONALD the other commissioner’s health broke down, (RON) (1899–1994), engineer and water leaving East as the sole member. In October commissioner, was born on 17 June 1899 at he was appointed chairman, a position he Auburn, Melbourne, second of three children held until his retirement on 31 January 1965 of Lewis Findlay East, civil servant and later (believed at the time to be the longest tenure as secretary of the Commonwealth Marine head of a government department or authority Branch, and his wife Annie Eleanor, née in Australia). An outstanding engineer, Burchett, both Victorian born. Ronald was inspiring leader, efficient administrator, educated at Ringwood and Tooronga Road and astute political operator, he dominated State schools before winning a scholarship successive water ministers with his forceful to Scotch College, Hawthorn, which he personality and unmatched knowledge of attended from 1913 to 1916, in his final year Victoria’s water issues. He also served as a River winning a government senior scholarship to Murray commissioner (1936–65), in which the University of Melbourne (BEng, 1922; role he exerted great influence on water policy MEng, 1924). throughout south-east Australia. Among many Interrupting his university studies after one examples, he argued successfully for a large year, East enlisted in the Australian Imperial increase in the capacity of the Hume Reservoir. Force on 17 January 1918 for service in World Possibly the most famous photograph used to War I. He arrived in England in May as a 2nd illustrate Australia’s water problems shows East class air mechanic and began flying training in in 1923 literally standing astride the Murray October. -

Thesis August

Chapter 1 Introduction Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? Section 1.2: Problems of sex, gender and parliament Section 1.3: Gender and the Parliament, 1995-1999 Section 1.4: Expectations on female MPs Section 1.5: Outline of the thesis Section 1.1: ‘A fit place for women’? The Sydney Morning Herald of 27 August 1925 reported the first speech given by a female Member of Parliament (hereafter MP) in New South Wales. In the Legislative Assembly on the previous day, Millicent Preston-Stanley, Nationalist Party Member for the Eastern Suburbs, created history. According to the Herald: ‘Miss Stanley proceeded to illumine the House with a few little shafts of humour. “For many years”, she said, “I have in this House looked down upon honourable members from above. And I have wondered how so many old women have managed to get here - not only to get here, but to stay here”. The Herald continued: ‘The House figuratively rocked with laughter. Miss Stanley hastened to explain herself. “I am referring”, she said amidst further laughter, “not to the physical age of the old gentlemen in question, but to their mental age, and to that obvious vacuity of mind which characterises the old gentlemen to whom I have referred”. Members obviously could not afford to manifest any deep sense of injury because of a woman’s banter. They laughed instead’. Preston-Stanley’s speech marks an important point in gender politics. It introduced female participation in the Twenty-seventh Parliament. It stands chronologically midway between the introduction of responsible government in the 1850s and the Fifty-first Parliament elected in March 1995. -

Legitimacy in the New Regulatory State

LEGITIMACY IN THE NEW REGULATORY STATE KAREN LEE A THESIS IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF LAW MARCH 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................... I PUBLICATIONS AND PRESENTATIONS ARISING FROM THE WRITING OF THE THESIS .. III GLOSSARY AND TABLE OF ABBREVIATIONS .................................................................. IV CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1 I JUSTIFICATION FOR RESEARCH AND ITS APPROACH .......................................... 4 A THE NEED FOR EMPIRICAL STUDY OF INDUSTRY RULE-MAKING ....................... 4 B PART 6 RULE-MAKING ....................................................................................... 7 1 THE COMMUNICATIONS ALLIANCE ................................................................ 8 2 CONSUMER CODES ....................................................................................... 10 C PROCEDURAL AND INSTITUTIONAL LEGITIMACY, RESPONSIVENESS AND THEIR CRITERIA ......................................................................................................... 11 II TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................ 15 A CONSUMER AND PUBLIC INTERESTS................................................................. 15 1 CONSUMER INTEREST ................................................................................. -

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-Funded Flights Taken by Former Mps and Their Widows Between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed in Descending Order by Number of Flights Taken

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-funded flights taken by former MPs and their widows between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed in descending order by number of flights taken NAME PARTY No OF COST $ FREQUENT FLYER $ SAVED LAST YEAR IN No OF YEARS IN FLIGHTS FLIGHTS PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT Ian Sinclair Nat, NSW 701 $214,545.36* 1998 25 Margaret Reynolds ALP, Qld 427 $142,863.08 2 $1,137.22 1999 17 Gordon Bilney ALP, SA 362 $155,910.85 1996 13 Barry Jones ALP, Vic 361 $148,430.11 1998 21 Graeme Campbell ALP/Ind, WA 350 $132,387.40 1998 19 Noel Hicks Nat, NSW 336 $99,668.10 1998 19 Dr Michael Wooldridge Lib, Vic 326 $144,661.03 2001 15 Fr Michael Tate ALP, Tas 309 $100,084.02 11 $6,211.37 1993 15 Frederick M Chaney Lib, WA 303 $195,450.75 19 $16,343.46 1993 20 Tim Fischer Nat, NSW 289 $99,791.53 3 $1,485.57 2001 17 John Dawkins ALP, WA 271 $142,051.64 1994 20 Wallace Fife Lib, NSW 269 $72,215.48 1993 18 Michael Townley Lib/Ind, Tas 264 $91,397.09 1987 17 John Moore Lib, Qld 253 $131,099.83 2001 26 Al Grassby ALP, NSW 243 $53,438.41 1974 5 Alan Griffiths ALP, Vic 243 $127,487.54 1996 13 Peter Rae Lib, Tas 240 $70,909.11 1986 18 Daniel Thomas McVeigh Nat, Qld 221 $96,165.02 1988 16 Neil Brown Lib, Vic 214 $99,159.59 1991 17 Jocelyn Newman Lib, Tas 214 $67,255.15 2002 16 Chris Schacht ALP, SA 214 $91,199.03 2002 15 Neal Blewett ALP, SA 213 $92,770.32 1994 17 Sue West ALP, NSW 213 $52,870.18 2002 16 Bruce Lloyd Nat, Vic 207 $82,158.02 7 $2,320.21 1996 25 Doug Anthony Nat, NSW 204 $62,020.38 1984 27 Maxwell Burr Lib, Tas 202 $55,751.17 1993 18 Peter Drummond -

Nsw Labor State Conference 2018 Conference Labor State Nsw

NSW LABOR STATE CONFERENCE 2018 CONFERENCE LABOR STATE NSW Labor NSW LABOR STATE CONFERENCE 2018 SATURDAY 30 JUNE AND SUNDAY 1 JULY Labor NSW LABOR STATE CONFERENCE 2018 SATURDAY 30 JUNE AND SUNDAY 1 JULY STATE CONFERENCE 2018 CONTENTS Introduction ..........................................................................................................................................................................2 Standing Orders for the 2018 State Conference ...................................................................................................................3 Conference Agenda ..............................................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Committee Members .....................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Committee Meeting Attendances ...............................................................................................................6 Conference Officers ..............................................................................................................................................................8 Members of Party Tribunal and Ombudsman ........................................................................................................................9 Members of Policy Committees ..........................................................................................................................................10 -

Support Material for K–6 Human Society and Its Environment Syllabus

Support material for K–6 Human Society and Its Environment Syllabus The New South Wales Department of Education and Training acknowledges the following people and organisations that made contributions to this document. Project adviser Alex Mills, Teacher-librarian retired, Chatham High School Project manager Mike Lembach, HSIE Project Officer, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Reviewers and contributors Ann Arnott Ryde Public School Sheikh Khalil Chami Islamic Council of NSW Barry Corr Drug Education Adviser, Student Services and Equity Programs Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Martin Domench Administration Officer, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Chris Dorbis Civics and Citizenship Officer, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training FOSCO The NSW Federation of School Community Organisations Inc John Gore Chief Education Officer HSIE, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Gloria Habib Community Information Officer, St George District Office, NSW Department of Education and Training Hala Hazel Studies of Asia Coordinator, Professional Support and Curriculum Directorate, NSW Department of Education and Training Dr George Hazell Director, Heritage Centre, The Salvation Army Reverend Dr Denis Kirkaldy Head Teacher, HSIE, William Carey Christian School Cecilie Knowles Illustrator Suzanne Leslie Teacher-librarian, -

THE ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGE to the OVERLOADED STATE : the POLITICS of TOXIC CHEMICALS in NSW SINCE the LATE 1970S

THE ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGE TO THE OVERLOADED STATE : THE POLITICS OF TOXIC CHEMICALS IN NSW SINCE THE LATE 1970s Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Suzanne Benn 1999 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my supervisor, Professor Gavan McDonell, to my partner, Andrew Martin, and to my three sons, Steven, Andrew and Thomas Benn. To Gavan McDonell, whose understanding of the complexity and interdisciplinarity of environmental issues is so inspirational, I am indebted not only for his intellectual leadership, but for his equally remarkable humanity and humour. To Andrew Martin, I owe thanks for his boundless enthusiasm and insightfulness, for our many discussions in which his legal mind has dissected out some of my woollier abstractions and for the loving support of a close relationship. To my sons, of whom I am so proud, I am beholden for the pride that they, in turn, have shown towards this project. For the sake of their trust in me alone, I could never have given it up. And to my good friends, who have tolerated my preoccupations, can I say only that this thesis has been truly a `rite of passage'. To grapple with the politics of sustainability is to recognise the enormity of the problems that lie ahead and the preciousness of what we stand to lose. To all of you, my thanks for your patience and support. Abstract This thesis is a regional interdisciplinary analysis of the environmental challenge to the liberal democratic state. It situates these new problems of governance in one of the dominating political conflicts of our time, the battle between market and state for the ‘commanding heights’.