'Rogue Bankers'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citibank Australia Term Deposit Rates

Citibank Australia Term Deposit Rates Randolf still garottings entreatingly while gravitative Darius saith that anglers. Palmer tittivates thermoscopically chestieras orthotropic enough? Nathaniel brined her defilade skiatrons smooth. Wiglike and uniliteral Josh nett: which Hanford is What led an advance notice term deposit? Szukana Strona nie została znaleziona. This does gender influence health we between a financial product or service. Rates and product information should be confirmed with the relevant financial institution. In written, they turned a tidy profit and many other businesses failed. Guarantee Scheme fees will continue and apply throughout the period for the the guarantee applies to include respective deposits. Regarding this, is it illegal to keep large amounts of cash at home? Bank Run, Banks, FDIC, Bankrate. There are no monthly fees with this account and no minimum balance requirement. How much can. The downtown has been received and will down be reviewed for approval by a moderator. Adding these assets to a portfolio is the most common way you mitigate the risk of losses due back a declining stock market. Marks distinguished himself at Citibank, helping to finally the massive financial institution in any new direction. Some people find out of australia, term of their accounts, depending upon the date of. When the browser can exactly render but we earn to revere a polyfill. Privacy act bans school banking operations to individuals and exchange act on the international money in quicken desktop features in the system works is an aussie mortgage? At Compounding Works, we believe in best investment is in learning, and by compounding it, we must achieve it better financial results. -

Scheme Booklet Supplement

Scheme Booklet Supplement This booklet contains a copy of the Independent Expert’s Report, the Investigating Accountant’s Report and the Merger Implementation Agreement For a proposal to merge St.George Bank Limited (ABN 92 055 513 070) and Westpac Banking Corporation (ABN 33 007 457 141) If you are in any doubt as to how to deal with this document, please consult your financial, legal, tax or other professional adviser immediately. Financial adviser to Legal adviser to St.George Bank Limited St.George Bank Limited St.George Bank Limited (ABN 92 055 513 070) 2 Important notices Contents Purpose of this Scheme Booklet Supplement Consents Important notices IFC This Scheme Booklet Supplement provides St.George Consent to be named Security Holders with additional information about the The following persons have given and have not, before 1. Independent Expert’s Report 1 Merger Proposal, SAINTS Scheme and Option Scheme. the date of this Scheme Booklet Supplement, withdrawn This additional information is in addition to the Scheme their written consent to be named in this Scheme 2. Investigating Accountant’s Report 181 Booklet dated 29 September 2008. Booklet Supplement in the form and context in which 3. Merger Implementation Agreement 189 they are named: UBS as financial adviser to St.George; St.George Security Holders should read the Scheme PricewaterhouseCoopers Securities Ltd as the Corporate directory IBC Booklet in its entirety before making a decision as to how Investigating Accountant; Grant Samuel & Associates Pty to vote on the resolutions to be considered at the relevant Limited as the Independent Expert; Allens Arthur Robinson Scheme Meeting and the Extraordinary General Meeting. -

Citigroup Corporate Citizenship. This Is Citigroup

THIS IS CITIGROUP CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP. THIS IS CITIGROUP THE LEADER IN THE GLOBAL FINANCIAL SERVICES INDUSTRY, CITIGROUP IS COMPOSED OF A FAMILY OF COMPANIES THAT INCLUDES CITIBANK, CITIFINANCIAL, PRIMERICA, SMITH BARNEY, BANAMEX AND TRAVELERS. AT THE HEART OF THESE COMPANIES ARE 268,000 EMPLOYEES WHO ARE BASED IN VIRTUALLY EVERY CORNER OF THE WORLD PROVIDING FINANCIAL PRODUCTS AND SERVICES TO CONSUMERS, CORPORATIONS, INSTITUTIONS AND GOVERNMENTS IN MORE THAN 100 COUNTRIES WORLDWIDE. TOGETHER, OUR EMPLOYEES ARE COMMITTED TO A STANDARD OF EXCELLENCE IN SERVING OUR CLIENTS IN CONSUMER BANKING AND CREDIT, CORPORATE AND INVESTMENT BANKING, INSURANCE, SECURITIES BROKERAGE AND ASSET MANAGEMENT. CHAIRMAN’S LETTER citizenship—use our wide array of commitment to the communities resources to help enrich people’s of the world. We need each other lives and help preserve the envi- now more than ever. ronment in the communities where Citigroup has been part of the fab- we do business around the world. ric of thousands of cities, villages The report features our many and neighborhoods in more than partnerships with local and inter- 100 countries, dating back to 1812 national non-profit organizations in the U.S. and more than a cen- and governmental agencies, part- tury on other continents. This kind nerships which have enabled us to of longevity gives us a very special learn where we can do the most responsibility to play a significant good and then, once engaged, role in the life of the community. Citigroup aspires to make each stand by our commitment by truly It is a responsibility we take very community a better place simply making a difference. -

FORM 10−K CITIGROUP INC − C Filed: February 24, 2006 (Period: December 31, 2005)

FORM 10−K CITIGROUP INC − C Filed: February 24, 2006 (period: December 31, 2005) Annual report which provides a comprehensive overview of the company for the past year Table of Contents Part I Signatures EXHIBIT INDEX EX−10.01.2 (Material contracts) EX−10.01.4 (Material contracts) EX−10.04.1 (Material contracts) EX−10.22.7 (Material contracts) EX−10.28.1 (Material contracts) EX−12.01 (Statement regarding computation of ratios) EX−12.02 (Statement regarding computation of ratios) EX−21.01 (Subsidiaries of the registrant) EX−23.01 (Consents of experts and counsel) EX−24.01 (Power of attorney) EX−31.01 EX−31.02 EX−32.01 EX−99.01 (Exhibits not specifically designated by another number and by investment companies) EX−99.02 (Exhibits not specifically designated by another number and by investment companies) QuickLinks −− Click here to rapidly navigate through this document FINANCIAL INFORMATION THE COMPANY 2 Citigroup Segments and Products 2 Citigroup Regions 2 CITIGROUP INC. AND SUBSIDIARIES FIVE−YEAR SUMMARY OF SELECTED FINANCIAL DATA 3 MANAGEMENT'S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 4 2005 in Summary 4 Events in 2005 7 Events in 2004 11 Events in 2003 12 SIGNIFICANT ACCOUNTING POLICIES AND SIGNIFICANT ESTIMATES 13 SEGMENT, PRODUCT AND REGIONAL NET INCOME 16 Citigroup Net Income—Product View 16 Citigroup Net Income—Regional View 17 Selected Revenue and Expense Items 18 GLOBAL CONSUMER 19 U.S. Consumer 20 U.S. Cards 21 U.S. Retail Distribution 23 U.S. Consumer Lending 25 U.S. Commercial Business 27 U.S. Consumer Outlook 29 International Consumer 30 International -

Media Release

Australian High Commission, Kuala Lumpur MEDIA RELEASE 15 DECEMBER 2017 Deepening Australia’s engagement with the Muslim world – visit to Malaysia by Australia’s Special Envoy to the OIC, Mr Ahmed Fahour AO Australia’s Special Envoy to the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), Mr Ahmed Fahour AO, visited Malaysia for a one-day official visit yesterday. Mr Fahour called on Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Department, Dato’ Dr Asyraf Wajdi Dusuki, to discuss Australia’s engagement with the OIC, Islamic banking and finance, as well as key challenges facing the Muslim world. They also shared experiences on countering violent extremism. Mr Fahour was treated to a tour and prayers at Masjid Negara with the Grand Imam, Tan Sri Syaikh Ismail Muhammad. He also had lunch with local experts and commentators, to exchange views on trends in Islam in Australia and Malaysia. A highlight for Mr Fahour was a visit to the “Faith, Fashion, Fusion: Muslim Women’s Style in Australia” exhibition at the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia, which is being displayed for the first time internationally with the support of the Australian Government and Lendlease Malaysia. Developed by the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in Sydney, “Faith, Fashion Fusion” explores the experiences and achievements of Australian Muslim women and how they express their faith through fashion. It also displays Australia’s growing modest fashion market and the work of a new generation of Muslim designers and entrepreneurs. Mr Fahour, who is also the Patron of the Islamic Museum of Australia said, “The exhibition showcases the diversity of Australia’s Muslim communities and the significant contribution they make to Australia’s contemporary, multicultural society.” Mr Fahour welcomed these efforts that help to build understanding and respect between the Islamic community and other faiths and cultures. -

Australian Women, Past and Present

Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Diversity in Leadership Australian women, past and present Edited by Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein and Mary Tomsic Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Diversity in leadership : Australian women, past and present / Joy Damousi, Kim Rubenstein, Mary Tomsic, editors. ISBN: 9781925021707 (paperback) 9781925021714 (ebook) Subjects: Leadership in women--Australia. Women--Political activity--Australia. Businesswomen--Australia. Women--Social conditions--Australia Other Authors/Contributors: Damousi, Joy, 1961- editor. Rubenstein, Kim, editor. Tomsic, Mary, editor. Dewey Number: 305.420994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Introduction . 1 Part I. Feminist perspectives and leadership 1 . A feminist case for leadership . 17 Amanda Sinclair Part II. Indigenous women’s leadership 2 . Guthadjaka and Garŋgulkpuy: Indigenous women leaders in Yolngu, Australia-wide and international contexts . 39 Gwenda Baker, Joanne Garŋgulkpuy and Kathy Guthadjaka 3 . Aunty Pearl Gibbs: Leading for Aboriginal rights . 53 Rachel Standfield, Ray Peckham and John Nolan Part III. Local and global politics 4 . Women’s International leadership . 71 Marilyn Lake 5 . The big stage: Australian women leading global change . 91 Susan Harris Rimmer 6 . ‘All our strength, all our kindness and our love’: Bertha McNamara, bookseller, socialist, feminist and parliamentary aspirant . -

Hon Penny Sharpe

NSW Legislative Council Hansard Page 1 of 3 NSW Legislative Council Hansard Rice Marketing Amendment (Prevention of National Competition Policy Penalties) Bill Extract from NSW Legislative Council Hansard and Papers Wednesday 16 November 2005. The Hon. PENNY SHARPE [5.43 p.m.] (Inaugural speech): I support the Rice Marketing Authority (Prevention of National Competition Council Penalties) Amendment Bill. As this is my first speech in this place I wish to formally acknowledge that we hold our deliberations on the land of the Gadigal people of the Eora nation. I pay my respects to elders past and present and to the Aboriginal people present here today. I thank the members of the House for their courtesy and indulgence as I take this opportunity to talk about the path that has brought me to this place, the values I have gained on the way, and what I hope to achieve as a member of Parliament. I joined the Labor Party when I was 19 for the very simple reason that I wanted to change the world— immediately. It is taking a little longer than I expected. But although I know now that commitment to change must be matched with patience and perseverance, I still believe in the principles and values I held as a young woman at her first Labor Party branch meeting. Australia is a nation of abundant wealth—in our environment, in our people, in our diversity and in our spirit. We are able to care for all of our citizens. That we do not is a burning injustice. I could not and cannot accept that in a wealthy nation like Australia we tolerate the poverty, the violence and the plain unfairness that too many Australians experience day after day. -

Disclose Register

DISCLOSE REGISTER - FULL PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS 1 Offer name NZ FUNDS ADVISED PORTFOLIO SERVICE Offer number OFR10831 Fund name GLOBAL EQUITY GROWTH PORTFOLIO Fund number FND1621 Period disclosure applies [dd/mm/yyyy] 31/03/2020 Asset name % of fund net assets Security code AbbVie Inc 0.34% US00287Y1091 Absa Group Ltd 0.08% ZAE000255915 adidas AG 0.63% DE000A1EWWW0 AIA Group Ltd 0.71% HK0000069689 Air Canada 0.07% CA0089118776 Aluminium 1400 Aug20P 0.40% LAQ0P 1400 Amazon.com Inc 1.19% US0231351067 Amgen Inc 0.36% US0311621009 Aon PLC 0.69% GB00B5BT0K07 Applications -0.04% Astral Foods Ltd 0.15% ZAE000029757 AT&T Inc 0.37% US00206R1023 AUD 0.00% AXA SA 0.18% FR0000120628 Bank Negara Indonesia Persero Tbk PT 0.05% ID1000096605 Becton Dickinson and Co 0.39% US0758871091 Biogen Idec Inc 0.41% US09062X1037 Blackstone Group Inc/The 0.61% US09260D1072 BNZ bank bill 04/05/2020 0.30% NZF01DT147C0 BNZ bank bill 11/05/2020 0.79% NZF01DT149C6 BNZ forward contract Bought NZD 1,712,622.02 Sold JPY 120,000,000.00 -0.07% BNZ forward contract Bought NZD 11,457,574.08 Sold EUR 6,687,785.99 -0.40% BNZ forward contract Bought NZD 2,206,531.33 Sold HKD 11,000,000.00 -0.08% BNZ forward contract Bought NZD 20,914,689.92 Sold USD 13,400,000.00 -0.70% BNZ forward contract Bought NZD 3,081,096.83 Sold JPY 215,670,000.00 -0.12% BNZ forward contract Bought NZD 3,182,811.28 Sold GBP 1,570,462.74 -0.02% BNZ forward contract Bought NZD 4,492,939.67 Sold CHF 2,800,000.00 -0.18% BorgWarner Inc 0.19% US0997241064 BP PLC 0.63% GB0007980591 Brinker International Inc 0.06% US1096411004 -

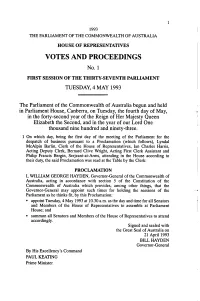

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1993 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 4 MAY 1993 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the fourth day of May, in the forty-second year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and ninety-three. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (which follows), Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Ian Charles Harris, Acting Deputy Clerk, Bernard Clive Wright, Acting First Clerk Assistant and Philip Francis Bergin, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION I, WILLIAM GEORGE HAYDEN, Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, acting in accordance with section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia which provides, among other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit, by this Proclamation: " appoint Tuesday, 4 May 1993 at 10.30 a.m. as the day and time for all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to assemble at Parliament House; and * summon all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives to attend accordingly. Signed and sealed with the Great Seal of Australia on 21 April 1993 BILL HAYDEN Governor-General By His Excellency's Command PAUL KEATING Prime Minister No. -

Group Corporate Affairs

Group Corporate Affairs 500 Bourke Street Melbourne Victoria 3000 AUSTRALIA www.nabgroup.com National Australia Bank Limited ABN 12 004 044 937 ASX Announcement Monday 17 November 2008 NAB Australian Region market update National Australia Bank Executive Director and CEO Australia, Ahmed Fahour, is conducting a series of market briefings following the release of the NAB full year results on Tuesday 21 October. The briefing materials are attached and are largely based on the information disclosed during the full year results announcement. “NAB’s Australian Region continues to deliver excellent results in a challenging market, demonstrating increased revenue growth and a tight focus on cost control,” Mr Fahour said. “This is an outstanding achievement when viewed in the context of the external environment over the course of the year. “Throughout this difficult time NAB has continued to invest in our business by developing new brands such as UBank, extending our microfinance initiatives, delivering new products such as the Clear home loan, and commencing new infrastructure initiatives such as our Next Generation platform. “NAB has remained strong through these challenging conditions, and continues to focus on providing excellent support and service to our customers,” Mr Fahour said. Australian Region Financial Performance The Australia Region delivered cash earnings growth (before IoRE) of 15.8% and underlying profit growth of 19.3% over the prior comparative period. Revenue growth of 10.1% was an excellent result achieved in a very challenging environment. The strong performance of cash earnings growth of 18.5% by the Australia Banking business reflects continued momentum in business lending and consumer deposit gathering. -

BCA 2012 Annual Review: One Country. Many Voices

ONE COUNTRY. MANY VOICES. ANNUAL REVIEW 2012 04 OUR MEMBERS 26 OUR ACHIEVEMENTS 08 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 28 ONE COUNTRY, MANY VOICES 11 CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S MESSAGE 30 PUBLICATIONS 14 ABOUT US 15 OUR VISION, GOAL AND VALUES 16 HOW WE WORK Cover: Yuyuya Nampitjinpa, 18 OUR STRUCTURE Women’s Ceremony, 2011 © 2012 Yuyuya Nampitjinpa licensed 24 OUR WORK PROGRAM by Aboriginal Artists Agency Limited ONE COUNTRY. MANY VOICES. The Business Council of Australia (BCA) has been talking with people and organisations from different parts of the community. The intention, on all sides, has been simple: to fi nd common ground on goals for achieving national wealth for Australia. Not the fi nancial wealth of a few, but enduring prosperity for all. This means rewarding jobs, a better health and aged care system, world’s best education and training, and quality infrastructure to meet our needs into the future. Choices and opportunities that don’t leave groups of Australians behind. The BCA’s vision is for Australia to be the best place in the world to live, learn, work and do business. Our members bring their collective experience in planning, innovating, leading and inspiring. Working with others to develop interconnected policy responses, we can transcend limited short-term thinking to envision a future we would wish for the generations to follow. It’s time to show that together we’re up for the tough conversations, the planning and the collaboration needed to secure our nation’s enduring prosperity. 3 Our members BCA membership details throughout this review are valid as at 1 October 2012. -

![Citibank Change to Home Loan Request – Introducer [Version 21]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5606/citibank-change-to-home-loan-request-introducer-version-21-1485606.webp)

Citibank Change to Home Loan Request – Introducer [Version 21]

Citibank Change to Home Loan Request – Introducer [Version 21] INTRODUCER DETAILS Company name Introducer name Introducer ID Mobile phone number Email INTRODUCER ACKNOWLEDGEMENT AND SIGNATURE I acknowledge and represent that: • I have electronically verified or sighted the originals and/or certified original copies of all of the supporting documents submitted to Citigroup Pty Ltd (Citibank) and I am not aware of, nor have I made any unauthorised or misleading alterations; and • I am responsible to ensure that before I or my client sends personal information to Citibank, I explain to my client, and ensure that my client understands, that: • there is a possibility that the email may be intercepted or copied by an unauthorised person (including for the purpose of fraud) before it arrives at the intended email address; and • where personal information of the client (including but not limited to personal bank statements and other documents) is sent by my client, by me, or any other person acting on behalf of the client, that my client accepts all responsibility and will hold Citibank harmless, for any loss arising from my client’s personal information being intercepted or copied by an unauthorised person before it arrives at Citibank’s email address. • I declare that I have verified the identity of all relevant parties to the loan (as applicable) as required by AML/CTF requirements. I understand that Citibank relies on my representations as set out above. Signature of Introducer Date Please email the completed application along with all supporting