Lupinus Nipomensis (Nipomo Lupine) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Ventura Fish and Wildlif

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park

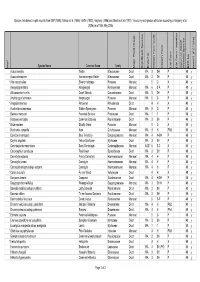

19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450 ■ 707.847.3437 ■ [email protected] ■ www.fortross.org Title: Vascular Plants at Fort Ross State Historic Park Author(s): Dorothy Scherer Published by: California Native Plant Society i Source: Fort Ross Conservancy Library URL: www.fortross.org Fort Ross Conservancy (FRC) asks that you acknowledge FRC as the source of the content; if you use material from FRC online, we request that you link directly to the URL provided. If you use the content offline, we ask that you credit the source as follows: “Courtesy of Fort Ross Conservancy, www.fortross.org.” Fort Ross Conservancy, a 501(c)(3) and California State Park cooperating association, connects people to the history and beauty of Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. © Fort Ross Conservancy, 19005 Coast Highway One, Jenner, CA 95450, 707-847-3437 .~ ) VASCULAR PLANTS of FORT ROSS STATE HISTORIC PARK SONOMA COUNTY A PLANT COMMUNITIES PROJECT DOROTHY KING YOUNG CHAPTER CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY DOROTHY SCHERER, CHAIRPERSON DECEMBER 30, 1999 ) Vascular Plants of Fort Ross State Historic Park August 18, 2000 Family Botanical Name Common Name Plant Habitat Listed/ Community Comments Ferns & Fern Allies: Azollaceae/Mosquito Fern Azo/la filiculoides Mosquito Fern wp Blechnaceae/Deer Fern Blechnum spicant Deer Fern RV mp,sp Woodwardia fimbriata Giant Chain Fern RV wp Oennstaedtiaceae/Bracken Fern Pleridium aquilinum var. pubescens Bracken, Brake CG,CC,CF mh T Oryopteridaceae/Wood Fern Athyrium filix-femina var. cyclosorum Western lady Fern RV sp,wp Dryopteris arguta Coastal Wood Fern OS op,st Dryopteris expansa Spreading Wood Fern RV sp,wp Polystichum munitum Western Sword Fern CF mh,mp Equisetaceae/Horsetail Equisetum arvense Common Horsetail RV ds,mp Equisetum hyemale ssp.affine Common Scouring Rush RV mp,sg Equisetum laevigatum Smooth Scouring Rush mp,sg Equisetum telmateia ssp. -

Ehrharta Calycina

Information on measures and related costs in relation to species considered for inclusion on the Union list: Ehrharta calycina This note has been drafted by IUCN within the framework of the contract No 07.0202/2017/763436/SER/ENV.D2 “Technical and Scientific support in relation to the Implementation of Regulation 1143/2014 on Invasive Alien Species”. The information and views set out in this note do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission, or IUCN. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this note. Neither the Commission nor IUCN or any person acting on the Commission’s behalf, including any authors or contributors of the notes themselves, may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. This document shall be cited as: Visser, V. 2018. Information on measures and related costs in relation to species considered for inclusion on the Union list: Ehrharta calycina. Technical note prepared by IUCN for the European Commission. Date of completion: 25/10/2018 Comments which could support improvement of this document are welcome. Please send your comments by e-mail to [email protected]. Species (scientific name) Ehrharta calycina Sm. Pl. Ic. Ined. t. 33. Species (common name) Perennial veldt grass, purple veldt grass, veldt grass, common ehrharta, gewone ehrharta (Afrikaans), rooisaadgras (Afrikaans). Author(s) Vernon Visser, African Climate & Development Institute Date Completed 25/10/2018 Reviewer Courtenay A. Ray, Arizona State University Summary Highlight of measures that provide the most cost-effective options to prevent the introduction, achieve early detection, rapidly eradicate and manage the species, including significant gaps in information or knowledge to identify cost-effective measures. -

Conceptual Design Documentation

Appendix A: Conceptual Design Documentation APPENDIX A Conceptual Design Documentation June 2019 A-1 APPENDIX A: CONCEPTUAL DESIGN DOCUMENTATION The environmental analyses in the NEPA and CEQA documents for the proposed improvements at Oceano County Airport (the Airport) are based on conceptual designs prepared to provide a realistic basis for assessing their environmental consequences. 1. Widen runway from 50 to 60 feet 2. Widen Taxiways A, A-1, A-2, A-3, and A-4 from 20 to 25 feet 3. Relocate segmented circle and wind cone 4. Installation of taxiway edge lighting 5. Installation of hold position signage 6. Installation of a new electrical vault and connections 7. Installation of a pollution control facility (wash rack) CIVIL ENGINEERING CALCULATIONS The purpose of this conceptual design effort is to identify the amount of impervious surface, grading (cut and fill) and drainage implications of the projects identified above. The conceptual design calculations detailed in the following figures indicate that Projects 1 and 2, widening the runways and taxiways would increase the total amount of impervious surface on the Airport by 32,016 square feet, or 0.73 acres; a 6.6 percent increase in the Airport’s impervious surface area. Drainage patterns would remain the same as both the runway and taxiways would continue to sheet flow from their centerlines to the edge of pavement and then into open, grassed areas. The existing drainage system is able to accommodate the modest increase in stormwater runoff that would occur, particularly as soil conditions on the Airport are conducive to infiltration. Figure A-1 shows the locations of the seven projects incorporated in the Proposed Action. -

Montaña De Oro Checklist-07Jun19

Checklist1 of Vascular Flora of Montaña de Oro State Park San Luis Obispo County, California (07 June 2019) David J. Keil Robert F. Hoover Herbarium Biological Sciences Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n Abronia latifolia yellow sand-verbena NYCTAGINACEAE v n Abronia maritima beach sand-verbena, red NYCTAGINACEAE 4.2 v sand-verbena n Abronia umbellata var. umbellata purple sand-verbena NYCTAGINACEAE v n Acer macrophyllum big-leaf maple SAPINDACEAE v n ❀ Achillea millefolium yarrow ASTERACEAE v n Acmispon brachycarpus shortpod deervetch FABACEAE v 1 Please notify the author of additions or corrections to this list ([email protected]). ❀ — See Wildflowers of San Luis Obispo, California, second edition (2018) for photograph. Most are illustrated in the first edition as well; old names for some species in square brackets. n — California native n1 — California native but planted at Montaña de Oro. i — exotic species, introduced to California, naturalized or waif. v — documented by one or more specimens (Consortium of California Herbaria record; specimen in OBI; or collection that has not yet been accessioned) o — observed during field surveys; no voucher specimen known R—California Rare Plant Rank Scientific Name Common Name Family Rare n ❀ Acmispon glaber var. glaber common deerweed FABACEAE v n Acmispon heermannii var. orbicularis woolly deer-vetch FABACEAE v n Acmispon junceus var. biolettii Biolett's rush deerweed FABACEAE v n Acmispon junceus var. junceus common rush deerweed FABACEAE v n Acmispon maritimus var. maritimus coastal deer-vetch FABACEAE v n Acmispon micranthus fishhook deervetch FABACEAE v n Acmispon parviflorus miniature deervetch FABACEAE o n ❀ Acmispon strigosus strigose deer-vetch FABACEAE v n Actaea rubra baneberry RANUNCULACEAE v n ❀ Adelinia grandis Pacific hound's tongue BORAGINACEAE v n ❀ Adenostoma fasciculatum var. -

BFS048 Site Species List

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Mcgrath State Beach Plants 2/14/2005 7:53 PM Vascular Plants of Mcgrath State Beach, Ventura County, California by David L

Vascular Plants of McGrath State Beach, Ventura County, California By David L. Magney Scientific Name Common Name Habit Family Abronia maritima Red Sand-verbena PH Nyctaginaceae Abronia umbellata Beach Sand-verbena PH Nyctaginaceae Allenrolfea occidentalis Iodinebush S Chenopodiaceae Amaranthus albus * Prostrate Pigweed AH Amaranthaceae Amblyopappus pusillus Dwarf Coastweed PH Asteraceae Ambrosia chamissonis Beach-bur S Asteraceae Ambrosia psilostachya Western Ragweed PH Asteraceae Amsinckia spectabilis var. spectabilis Seaside Fiddleneck AH Boraginaceae Anagallis arvensis * Scarlet Pimpernel AH Primulaceae Anemopsis californica Yerba Mansa PH Saururaceae Apium graveolens * Wild Celery PH Apiaceae Artemisia biennis Biennial Wormwood BH Asteraceae Artemisia californica California Sagebrush S Asteraceae Artemisia douglasiana Douglas' Sagewort PH Asteraceae Artemisia dracunculus Wormwood PH Asteraceae Artemisia tridentata ssp. tridentata Big Sagebrush S Asteraceae Arundo donax * Giant Reed PG Poaceae Aster subulatus var. ligulatus Annual Water Aster AH Asteraceae Astragalus pycnostachyus ssp. lanosissimus Ventura Marsh Milkvetch PH Fabaceae Atriplex californica California Saltbush PH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex lentiformis ssp. breweri Big Saltbush S Chenopodiaceae Atriplex patula ssp. hastata Arrowleaf Saltbush AH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex patula Spear Saltbush AH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex semibaccata Australian Saltbush PH Chenopodiaceae Atriplex triangularis Spearscale AH Chenopodiaceae Avena barbata * Slender Oat AG Poaceae Avena fatua * Wild -

Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plant List

UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve Plants Below is the most recently updated plant list for UCSC Fort Ord Natural Reserve. * non-native taxon ? presence in question Listed Species Information: CNPS Listed - as designated by the California Rare Plant Ranks (formerly known as CNPS Lists). More information at http://www.cnps.org/cnps/rareplants/ranking.php Cal IPC Listed - an inventory that categorizes exotic and invasive plants as High, Moderate, or Limited, reflecting the level of each species' negative ecological impact in California. More information at http://www.cal-ipc.org More information about Federal and State threatened and endangered species listings can be found at https://www.fws.gov/endangered/ (US) and http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ t_e_spp/ (CA). FAMILY NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME LISTED Ferns AZOLLACEAE - Mosquito Fern American water fern, mosquito fern, Family Azolla filiculoides ? Mosquito fern, Pacific mosquitofern DENNSTAEDTIACEAE - Bracken Hairy brackenfern, Western bracken Family Pteridium aquilinum var. pubescens fern DRYOPTERIDACEAE - Shield or California wood fern, Coastal wood wood fern family Dryopteris arguta fern, Shield fern Common horsetail rush, Common horsetail, field horsetail, Field EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense horsetail Equisetum telmateia ssp. braunii Giant horse tail, Giant horsetail Pentagramma triangularis ssp. PTERIDACEAE - Brake Family triangularis Gold back fern Gymnosperms CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Hesperocyparis macrocarpa Monterey cypress CNPS - 1B.2, Cal IPC -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise. -

Morro Creek Natural Environment Study

Morro Creek Multi-Use Trail and Bridge Project Natural Environment Study San Luis Obispo County, California Federal Project Number CASB12RP-5391(013) MB-2013-S2 05-SLO-0-MOBY December 2013 For individuals with sensory disabilities, this document is available in Braille, large print, on audiocassette, or computer disk. To obtain a copy in one of these alternate formats, please call or write to Caltrans, Attn: Brandy Rider, Caltrans District 5 Environmental Stewardship Branch, 50 Higuera Street, San Luis Obispo, CA 93401; 805-549-3182 Voice, or use the California Relay Service TTY number, 805-549-3259. This page is intentionally left blank. Summary Summary The City of Morro Bay is extending the existing Harborwalk with continuation of a paved pedestrian boardwalk and separate Class I bike path from the existing parking area and crossing on Embarcadero Avenue northward. The City also proposes to install a clear-span pre-engineered/pre-fabricated bike and pedestrian bridge over Morro Creek to connect to north Morro Bay on Embarcadero Road/State Route 41. In addition, the project will include improvements to beach access from the trail, and two interpretive sign stations that will display educational and other information about the cultural and natural history of the region. This project is receiving funding from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and with assistance from Caltrans. As part of its NEPA assignment of federal responsibilities by the FHWA, effective October 1, 2012 and pursuant to 23 USC 326, Caltrans is acting as the lead federal agency for Section 7 of the federal Endangered Species Act. -

Unassisted Invasions: Understanding and Responding to Australia's High

CSIRO PUBLISHING Australian Journal of Botany, 2017, 65, 678–690 Turner Review No. 21 https://doi.org/10.1071/BT17152 Unassisted invasions: understanding and responding to Australia’s high-impact environmental grass weeds Rieks D. van Klinken A,C and Margaret H. Friedel B ACSIRO, EcoSciences Precinct, PO Box 2583, Brisbane, Qld 4001, Australia. BCSIRO, PO Box 2114, Alice Springs, NT 0871, Australia. CCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Alien grass species have been intentionally introduced into Australia since European settlement over 200 years ago, with many subsequently becoming weeds of natural environments. We have identified the subset of these weeds that have invaded and become dominant in environmentally important areas in the absence of modern anthropogenic disturbance, calling them ‘high-impact species’. We also examined why these high-impact species were successful, and what that might mean for management. Seventeen high-impact species were identified through literature review and expert advice; all had arrived by 1945, and all except one were imported intentionally, 16 of the 17 were perennial and four of the 17 were aquatic. They had become dominant in diverse habitats and climates, although some environments still remain largely uninvaded despite apparently ample opportunities. Why these species succeeded remains largely untested, but evidence suggests a combination of ecological novelty (both intended at time of introduction and unanticipated), propagule pressure (through high reproductive rate and dominance in nearby anthropogenically-disturbed habitats) and an ability to respond to, and even alter, natural disturbance regimes (especially fire and inundation). Serious knowledge gaps remain for these species, but indications are that resources could be better focused on understanding and managing this limited group of high-impact species. -

A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California

Humboldt State University Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University Botanical Studies Open Educational Resources and Data 3-2020 A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California James P. Smith Jr Humboldt State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Smith, James P. Jr, "A Checklist of Vascular Plants Endemic to California" (2020). Botanical Studies. 42. https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/botany_jps/42 This Flora of California is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources and Data at Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Botanical Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Humboldt State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A LIST OF THE VASCULAR PLANTS ENDEMIC TO CALIFORNIA Compiled By James P. Smith, Jr. Professor Emeritus of Botany Department of Biological Sciences Humboldt State University Arcata, California 13 February 2020 CONTENTS Willis Jepson (1923-1925) recognized that the assemblage of plants that characterized our flora excludes the desert province of southwest California Introduction. 1 and extends beyond its political boundaries to include An Overview. 2 southwestern Oregon, a small portion of western Endemic Genera . 2 Nevada, and the northern portion of Baja California, Almost Endemic Genera . 3 Mexico. This expanded region became known as the California Floristic Province (CFP). Keep in mind that List of Endemic Plants . 4 not all plants endemic to California lie within the CFP Plants Endemic to a Single County or Island 24 and others that are endemic to the CFP are not County and Channel Island Abbreviations . -

Epitypification of Tilletia Ehrhartae, a Smut Fungus with Potential For

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Eur J Plant Pathol (2015) 143:151–158 DOI 10.1007/s10658-015-0672-1 Epitypification of Tilletia ehrhartae,asmutfungus with potential for nature conservation, biosecurity and biocontrol Marcin Piątek & Matthias Lutz & Adriaana Jacobs & Francis Villablanca & Alan R. Wood Accepted: 1 May 2015 /Published online: 21 May 2015 # The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Tilletia ehrhartae, a smut fungus infecting caused by Tilletia indica (which is absent in Australia), perennial veldtgrass Ehrharta calycina,isepitypified and therefore constituting a potential risk for Australian and characterized using the Consolidated Species Con- wheat export. The current global distribution of Tilletia cept, including morphology, ecology (host plant) and ehrhartae, possible colonization history, and potential rDNA sequences (ITS and LSU). Tilletia ehrhartae is for nature conservation, biosecurity and biocontrol are native and endemic to the Cape Floral Kingdom discussed. The sequences generated in this work could (located entirely in South Africa), but it has also been serve as DNA barcodes to facilitate rapid identification introduced to the alien artificial range of Ehrharta of this important species. calycina in Australia and California. This smut has already caused some biosecurity problems in Australia Keywords Australia . California . Cape Floral as its spores were found to contaminate harvested wheat Kingdom . South Africa . Epitype . Plant pathogens . seeds, leading to confusion with Karnal bunt of wheat DNA barcodes M. Piątek (*) Department of Mycology, W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Introduction Polish Academy of Sciences, Lubicz 46, PL-31-512 Kraków, Poland The plant pathogenic teliosporic smut fungi are predom- e-mail: [email protected] inantly distributed with host plants growing in natural M.