Leveraging Liminality: the Border Town of Baoean (Shenzhen) And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 1 (2013) R. MAK & C. CHAN Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong Ricardo K. S. MAK & Catherine S. CHAN Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong S.A.R., China Abstract: Icons, which take the form of images, artifacts, landmarks, or fictional figures, represent mounds of meaning stuck in the collective unconsciousness of different communities. Icons are shortcuts to values, identity or feelings that their users collectively share and treasure. Through the concrete identification and analysis of icons of post-war Hong Kong, this paper attempts to highlight not only Hong Kong people’s changing collective needs and mental or material hunger, but also their continuous search for identity. Keywords: Icons, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Chinese, 1997, values, identity, lifestyle, business, popular culture, fusion, hybridity, colonialism, economic takeoff, consumerism, show business 1. Introduction: Telling Hong Kong’s Story through Icons It seems easy to tell the story of post-war Hong Kong. If merely delineating the sky-high synopsis of the city, the ups and downs, high highs and low lows are at once evidently remarkable: a collective struggle for survival in the post-war years, tremendous social instability in the 1960s, industrial take-off in the 1970s, a growth in economic confidence and cultural arrogance in the 1980s and a rich cultural upheaval in search of locality before the handover. The early 21st century might as well sum up the development of Hong Kong, whose history is long yet surprisingly short- propelled by capitalism, gnawing away at globalization and living off its elastic schizophrenia. -

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Modern Hong Kong

Modern Hong Kong Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History Modern Hong Kong Steve Tsang Subject: China, Hong Kong, Macao, and/or Taiwan Online Publication Date: Feb 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.280 Abstract and Keywords Hong Kong entered its modern era when it became a British overseas territory in 1841. In its early years as a Crown Colony, it suffered from corruption and racial segregation but grew rapidly as a free port that supported trade with China. It took about two decades before Hong Kong established a genuinely independent judiciary and introduced the Cadet Scheme to select and train senior officials, which dramatically improved the quality of governance. Until the Pacific War (1941–1945), the colonial government focused its attention and resources on the small expatriate community and largely left the overwhelming majority of the population, the Chinese community, to manage themselves, through voluntary organizations such as the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals. The 1940s was a watershed decade in Hong Kong’s history. The fall of Hong Kong and other European colonies to the Japanese at the start of the Pacific War shattered the myth of the superiority of white men and the invincibility of the British Empire. When the war ended the British realized that they could not restore the status quo ante. They thus put an end to racial segregation, removed the glass ceiling that prevented a Chinese person from becoming a Cadet or Administrative Officer or rising to become the Senior Member of the Legislative or the Executive Council, and looked into the possibility of introducing municipal self-government. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

2018 APSN Newsletter I

Issue 26, No. 25/2018 2018 APSN Newsletter I March, 2018 CONTENTS APSN News 1st President Meeting 2018 GPAS Workshop Programme (updated) GPAS 2017 Winners APEC News Industry News Upcoming APSN & Maritime Events 1st President Meeting The 1st President Meeting of the APSN was successfully held on 17-19 January, 2018 in Kunming, China. The meeting confirmed the date, venue, title and theme of 2018 key activities: Date and Venue •November 13-16, 2018 •Singapore Key Activities: •Title: Port Connectivity Forum and the 11th Council Meeting of APSN •Theme: Port Connectivity: Positioning Asia-Pacific Ports for the Future •APSN 10th Anniversary Celebration •GPAS 2017 & 2018 Awarding Ceremony Details please refer to: http://www.apecpsn.o rg/index.php?s=/New s/detail/clickType/aps nNews/id/816 2018 GPAS Workshop Programme (updated) Look forward to meeting you in Beijing! GPAS 2017 Winners Bintulu Port, Malaysia Chiwan Container Terminal Co., Ltd, China PSA Singapore, Singapore Johor Port Authority, Malaysia Port of Batangas, The Philippines Shekou Container Terminals Ltd, China Tan Cang Cat Lai Port, Viet Nam Details please refer to: http://www.apecpsn.org/index.php?s=/News/detail/clickType/apsnNews/id/817 Bintulu Port , Malaysia Bintulu Port began its operations on 1st January 1983. It is the largest and most efficient transport and distribution center in the Brunei Darussalam-Indonesia- Malaysia- Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA) region. Bintulu Port is an international port which is strategically located in North-East Sarawak along the route between the Far East and Europe. Bintulu Port is the main gateway for export of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Malaysia. -

A City's Legend

A City’s Legend How Shenzhen evolved from a fishing village into a pioneering metropolis volving from a fishing village, Shenzhen, in est place in Shenzhen to Hong Kong, was set up who now works as a volunteer in the village. As the south China’s Guangdong Province, is now as a trailblazer in the city. “walking history book” of the village, he loves to Eone of China’s megacities. It has been the In 1979, with the preferential policies of the share his story with visitors. “Without reform and country’s fastest growing economy over the past Shenzhen SEZ, people in Yumin Village organized opening up, it is hard to say what my life would be four decades. transportation teams of freight ships and opened like now,” he added. Shenzhen was set up as a city in January 1979, for business. Some entrepreneurs from Hong right after China adopted its reform and opening- Kong started renting houses in the village and Pioneering spirit up policy in December of the previous year. In converting them into factories. The rent went The development of the Shekou Industrial Zone 1980, it was upgraded to a Special Economic Zone straight into the villagers’ pockets. is another microcosm of the rapid growth of (SEZ) along with three other coastal cities in south In 1981, it built villa-style apartments for vil- Shenzhen. The industrial zone took the lead in China, with the aim of making it a pioneer in ex- lagers—luxurious for Chinese people at that time. breaking many shackles and tried every possible ploring ways to carry out reform and opening up. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript Pas been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissenation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from anytype of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material bad to beremoved, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with smalloverlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back ofthe book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell &Howell Information Company 300North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106-1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521·0600 THE LIN BIAO INCIDENT: A STUDY OF EXTRA-INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS IN THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY AUGUST 1995 By Qiu Jin Dissertation Committee: Stephen Uhalley, Jr., Chairperson Harry Lamley Sharon Minichiello John Stephan Roger Ames UMI Number: 9604163 OMI Microform 9604163 Copyright 1995, by OMI Company. -

List of Access Officer (For Publication)

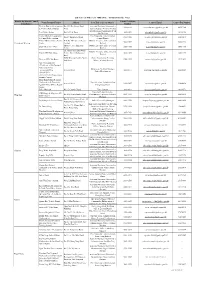

List of Access Officer (for Publication) - (Hong Kong Police Force) District (by District Council Contact Telephone Venue/Premise/FacilityAddress Post Title of Access Officer Contact Email Conact Fax Number Boundaries) Number Western District Headquarters No.280, Des Voeux Road Assistant Divisional Commander, 3660 6616 [email protected] 2858 9102 & Western Police Station West Administration, Western Division Sub-Divisional Commander, Peak Peak Police Station No.92, Peak Road 3660 9501 [email protected] 2849 4156 Sub-Division Central District Headquarters Chief Inspector, Administration, No.2, Chung Kong Road 3660 1106 [email protected] 2200 4511 & Central Police Station Central District Central District Police Service G/F, No.149, Queen's Road District Executive Officer, Central 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Central and Western Centre Central District Shop 347, 3/F, Shun Tak District Executive Officer, Central Shun Tak Centre NPO 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 Centre District 2/F, Chinachem Hollywood District Executive Officer, Central Central JPC Club House Centre, No.13, Hollywood 3660 1105 [email protected] 3660 1298 District Road POD, Western Garden, No.83, Police Community Relations Western JPC Club House 2546 9192 [email protected] 2915 2493 2nd Street Officer, Western District Police Headquarters - Certificate of No Criminal Conviction Office Building & Facilities Manager, - Licensing office Arsenal Street 2860 2171 [email protected] 2200 4329 Police Headquarters - Shroff Office - Central Traffic Prosecutions Enquiry Counter Hong Kong Island Regional Headquarters & Complaint Superintendent, Administration, Arsenal Street 2860 1007 [email protected] 2200 4430 Against Police Office (Report Hong Kong Island Room) Police Museum No.27, Coombe Road Force Curator 2849 8012 [email protected] 2849 4573 Inspector/Senior Inspector, EOD Range & Magazine MT. -

Guangshen Railway Company Limited Annual Report 2002

annual report 2002 Guangshen Railway Company Limited Guangshen Railway Company Limited Annual Report 2002 Annual Report Guangshen Railway Company Limited 2002 CONTENTS Company Profile 2 Financial Highlights 4 Chairman’s Statement 5 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 11 Report of Directors 24 Report of the Supervisory Committee 35 Directors, Supervisors and Senior Management 37 Corporate Information 41 Notice of Annual General Meeting 44 Auditors’ Report 46 Consolidated Income Statement 47 Consolidated Balance Sheet 48 Balance Sheet 49 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 50 Statements of Changes in Shareholders’ Equity 51 Notes to the Financial Statements 52 Financial Summary 93 Supplementary Financial Information 95 COMPANY PROFILE On 6 March, 1996, Guangshen Railway Company Limited (the “Company”) was registered and established in Shenzhen, the People’s Republic of China (the “PRC”) in accordance with the Company Law of the PRC. In May 1996, the H shares (“H Shares”) and American Depositary Shares (“ADSs”) issued by the Company were listed on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Hong Kong Exchange”) and the New York Stock Exchange, Inc. (“New York Stock Exchange”), respectively. The Company is currently the only enterprise engaging in the PRC railway transportation industry with its shares listed overseas. The Company is mainly engaged in railway passenger and freight transportation businesses between Guangzhou and Shenzhen and certain long-distance passenger transportation services. The Company also cooperates with Kowloon-Canton Railway Corporation (“KCR”) in Hong Kong in operating the Hong Kong through-train passenger service between Guangzhou and Kowloon. The Company provides consolidated services relating to railway facilities and technology. The Company also engages in commercial trading and other businesses that are consistent with the Company’s overall business strategy. -

July 2018 a Window to the Nation a Welcome to the World Vol

中国 画报 July 2018 A Window to the Nation A Welcome to the World Vol. 841 Shenzhen 40 Years Up 国内零售价: 10元 12-13 52-55 70-73 USA $5.10 UK ₤3.20 Australia $9.10 Europe €5.20 SCO Qingdao Brave New Beautiful Canada $7.80 Turkey TL.10.00 Summit: World of Ancient Things Cooperation for Chinese in the Palace 2-903 CN11-1429/Z the Future Sci-Fi Museum 邮发代号 可绕地球赤道栽种树木按已达塞罕坝机械林场的森林覆盖率寒来暑往,沙地变林海,荒原成绿洲。半个多世纪,三代人耕耘。牢记使命 80% , 1 米株距排开, 艰苦创业 12 圈。 绿色发展 Saihanba is a cold alpine area in northern Hebei Province bordering the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It was once a barren land but is now home to 75,000 hectares of forest, thanks to the labor of generations of forestry workers in the past 55 years. Every year the forest purifies 137 million cubic meters of water and absorbs 747,000 tons of carbon dioxide. The forest produces 12 billion yuan (around US$1.8 bil- lion) of ecological value annually, according to the Chinese Academy of Forestry. July 2O18 Administrative Agency: China International Publishing Group 主管:中国外文出版发行事业局 (中国国际出版集团) Publisher: China Pictorial Publications 主办: 社 Address: 33 Chegongzhuang Xilu 社址: Haidian, Beijing 100048 北京市海淀区车公庄西路33号 邮编: 100048 Email: [email protected] : [email protected] 邮箱 President: Yu Tao 社长: 于 涛 Editorial Board: Yu Tao, Li Xia, He Peng 编委会: Wang Lei, Bao Linfu, Yu Jia, Yan Ying 于 涛、李 霞、贺 鹏 王 磊、鲍林富、于 佳、闫 颖 Editor-in-Chief: Li Xia 总编辑: 李 霞 Editorial Directors: Wen Zhihong, Qiao Zhenqi 编辑部主任: 温志宏、乔振祺 English Editor: Liu Haile 英文定稿: 刘海乐 Editorial Consultants: Scott Huntsman, Mithila