Dab Denken Der Lehre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 10-2014 'Like Iron to a Magnet': Moses Hayim Luzzatto's Quest for Providence David Sclar Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/380 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence By David Sclar A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 David Sclar All Rights Reserved This Manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Prof. Jane S. Gerber _______________ ____________________________________ Date Chair of the Examining Committee Prof. Helena Rosenblatt _______________ ____________________________________ Date Executive Officer Prof. Francesca Bregoli _______________________________________ Prof. Elisheva Carlebach ________________________________________ Prof. Robert Seltzer ________________________________________ Prof. David Sorkin ________________________________________ Supervisory Committee iii Abstract “Like Iron to a Magnet”: Moses Hayim Luzzatto’s Quest for Providence by David Sclar Advisor: Prof. Jane S. Gerber This dissertation is a biographical study of Moses Hayim Luzzatto (1707–1746 or 1747). It presents the social and religious context in which Luzzatto was variously celebrated as the leader of a kabbalistic-messianic confraternity in Padua, condemned as a deviant threat by rabbis in Venice and central and eastern Europe, and accepted by the Portuguese Jewish community after relocating to Amsterdam. -

El Infinito Y El Lenguaje En La Kabbalah Judía: Un Enfoque Matemático, Lingüístico Y Filosófico

El Infinito y el Lenguaje en la Kabbalah judía: un enfoque matemático, lingüístico y filosófico Mario Javier Saban Cuño DEPARTAMENTO DE MATEMÁTICA APLICADA ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA SUPERIOR EL INFINITO Y EL LENGUAJE EN LA KABBALAH JUDÍA: UN ENFOQUE MATEMÁTICO, LINGÜÍSTICO Y FILOSÓFICO Mario Javier Sabán Cuño Tesis presentada para aspirar al grado de DOCTOR POR LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE Métodos Matemáticos y Modelización en Ciencias e Ingeniería DOCTORADO EN MATEMÁTICA Dirigida por: DR. JOSUÉ NESCOLARDE SELVA Agradecimientos Siempre temo olvidarme de alguna persona entre los agradecimientos. Uno no llega nunca solo a obtener una sexta tesis doctoral. Es verdad que medita en la soledad los asuntos fundamentales del universo, pero la gran cantidad de familia y amigos que me han acompañado en estos últimos años son los co-creadores de este trabajo de investigación sobre el Infinito. En primer lugar a mi esposa Jacqueline Claudia Freund quien decidió en el año 2002 acompañarme a Barcelona dejando su vida en la Argentina para crear la hermosa familia que tenemos hoy. Ya mis dos hermosos niños, a Max David Saban Freund y a Lucas Eli Saban Freund para que logren crecer y ser felices en cualquier trabajo que emprendan en sus vidas y que puedan vislumbrar un mundo mejor. Quiero agradecer a mi padre David Saban, quien desde la lejanía geográfica de la Argentina me ha estimulado siempre a crecer a pesar de las dificultades de la vida. De él he aprendido dos de las grandes virtudes que creo poseer, la voluntad y el esfuerzo. Gracias papá. Esta tesis doctoral en Matemática Aplicada tiene una inmensa deuda con el Dr. -

Illuminati Conspiracy Part One: a Precise Exegesis on the Available Evidence

http://www.conspiracyarchive.com/NWO/Illuminati.htm Illuminati Conspiracy Part One: A Precise Exegesis on the Available Evidence - by Terry Melanson, Aug. 5th, 2005 Illuminati Conspiracy Part Two: Sniffing out Jesuits A Metaprogrammer at the Door of Chapel Perilous In the literature that concerns the Illuminati relentless speculation abounds. No other secret society in recent history - with the exception of Freemasonry - has generated as much legend, hysteria, and disinformation. I first became aware of the the Illuminati about 14 years ago. Shortly thereafter I read a book, written by Robert Anton Wilson, called Cosmic Trigger: Final Secret of the Illuminati. Wilson published it in 1977 but his opening remarks on the subject still ring true today: Briefly, the background of the Bavarian Illuminati puzzle is this. On May 1, 1776, in Bavaria, Dr. Adam Weishaupt, a professor of Canon Law at Ingolstadt University and a former Jesuit, formed a secret society called the Order of the Illuminati within the existing Masonic lodges of Germany. Since Masonry is itself a secret society, the Illuminati was a secret society within a secret society, a mystery inside a mystery, so to say. In 1785 the Illuminati were suppressed by the Bavarian government for allegedly plotting to overthrow all the kings in Europe and the Pope to boot. This much is generally agreed upon by all historians. 1 Everything else is a matter of heated, and sometimes fetid, controversy. It has been claimed that Dr. Weishaupt was an atheist, a Cabalistic magician, a rationalist, a mystic; a democrat, a socialist, an anarchist, a fascist; a Machiavellian amoralist, an alchemist, a totalitarian and an "enthusiastic philanthropist." (The last was the verdict of Thomas Jefferson, by the way.) The Illuminati have also been credited with managing the French and American revolutions behind the scenes, taking over the world, being the brains behind Communism, continuing underground up to the 1970s, secretly worshipping the Devil, and mopery with intent to gawk. -

Download (4MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Role of The Intellect In The Medieval Jewish and Islamic Mystical Traditions: A Comparative Study Between R Abulafia and Shaykh Suhrawardi By MARLINE SHAHEEN A Special Study presented as part of the requirement for the degree of Master of Theology University of Glasgow March 2000 ProQuest Number: 10390791 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10390791 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. -

Franz Von BAADER's (1765 – 1841) Conception of Evolution in the Context of Contemporary Earth Sciences

Berichte der Geologischen Bundesanstalt ISSN 1017-8880, 101, Wien 2013 FRANZ, Inge Inge F RANZ Franz von BAADER's (1765 – 1841) Conception of Evolution in the Context of Contemporary Earth Sciences Inge FRANZ, Brockhausstraße 8, Leipzig Franz Xaver von BAADER (1765 - 1841) was a fully qualified physician who studied at the Freiberg Uni- versity of Mining and Technology from 1788 to 1792. He first gained practical mining experience in England and Scotland, besides he was active in his home province of Bavaria from 1796 onwards. Already in Freiberg, he published articles about technical innovations in mining. Following rationali- sation measures in Bavarian mining (including the mergers of several administrative departments), he was retired temporarily in 1820. He turned his attention primarily towards the humanities, but also continued to discuss problems relating to medicine and natural sciences. A comprehensive theory of evolution was only arrived at around the mid-nineteenth century. In the manner of a geological resume, BAADER, during his final year, emphasised his actualistic (uniformistic) directedness, the core themes of which he centred round the category of time: developmental- theoretical positions, especially those philosophical and scientific ones that were orientated on dy- namics. But how did the young BAADER approach evolutionist thinking? Here are some distinctive milestones. The existing level of knowledge starting from about the beginning of the 18th century until the end of that century is first outlined with examples that had some influence on BAADER's thinking. These begin with the universal scholar Gottfried Wilhelm LEIBNIZ (1646 - 1716), who presented essen- tial developmental-historical and conceptual, deterministic-dynamic substantiations, geologically applying these to include mining. -

Morgenstern Is a Senior Fellow at the Shalem Center in Jerusalem

Dispersion and the Longing for Zion, 1240-1840 rie orgenstern t has become increasingly accepted in recent years that Zionism is a I strictly modern nationalist movement, born just over a century ago, with the revolutionary aim of restoring Jewish sovereignty in the land of Israel. And indeed, Zionism was revolutionary in many ways: It rebelled against a tradition that in large part accepted the exile, and it attempted to bring to the Jewish people some of the nationalist ideas that were animat- ing European civilization in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centu- ries. But Zionist leaders always stressed that their movement had deep historical roots, and that it drew its vitality from forces that had shaped the Jewish consciousness over thousands of years. One such force was the Jewish faith in a national redemption—the belief that the Jews would ultimately return to the homeland from which they had been uprooted. This tension, between the modern and the traditional aspects of Zion- ism, has given rise to a contentious debate among scholars in Israel and elsewhere over the question of how the Zionist movement should be described. Was it basically a modern phenomenon, an imitation of the winter 5762 / 2002 • 71 other nationalist movements of nineteenth-century Europe? If so, then its continuous reference to the traditional roots of Jewish nationalism was in reality a kind of facade, a bid to create an “imaginary community” by selling a revisionist collective memory as if it had been part of the Jewish historical consciousness all along. Or is it possible to accept the claim of the early Zionists, that at the heart of their movement stood far more ancient hopes—and that what ultimately drove the most remarkable na- tional revival of modernity was an age-old messianic dream? For many years, it was the latter belief that prevailed among historians of Zionism. -

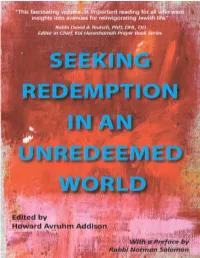

Seeking-Redemption-In-An-Unredeemed-World.Pdf

Praise for this book _________________________ The late Pope John Paul II once referred to the Jewish people as “our elder brothers in the faith of Abraham.” This insightful, probing, and very creative collection of essays on Jewish spirituality, edited by Rabbi Howard Addison, examines the many nuances of the Jewish understanding of redemption from a variety of perspectives and, in doing so, offers a fundamental backdrop against which Catholics and other Christians can examine their own understanding of the concept. For this reason, it is an invaluable tool for deepening our understanding of the roots our Christian heritage, challenging it, enriching it, and transforming it, so that we may enter into dialogue with our Jewish sisters and brothers and, indeed, with all who look to Abraham as their father in faith. Dennis J. Billy, C.Ss.R, ThD, STD, DMin John Cardinal Krol Chair of Moral Theology (2008-16) St. Charles Borromeo Seminary Author, Conscience and Prayer: The Spirit of Catholic Moral Theology Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, the founder of Judaism's Reconstructionist movement, taught that divine redemption is manifest in the human commitment to creativity and our efforts to achieve freedom. That understanding of salvation is exemplified in this fascinating volume. It explores spiritual direction, dance, art, liturgical innovation and social activism as practices for twenty-first- century spiritual renewal. In turn it connects them to Process Theology, beliefs in reincarnation and liberation theology in thought- provoking ways. It is important reading, especially for all who want insights into avenues for reinvigorating Jewish life. Rabbi David A. Teutsch, PhD, DHL, DD Wiener Professor Emeritus, Reconstructionist Rabbinical College Editor in Chief, Kol Haneshamah Prayer Book Series Seeking Redemption in an Unredeemed World offers fresh and diverse Jewish perspectives on the concept of redemption in Jewish life. -

The Ontology of Evil: Schelling and Pareyson

The Ontology of Evil: Schelling and Pareyson A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Daniele Fulvi PhD Candidate in Philosophy Western Sydney University School of Humanities and Communication Arts 2020 Acknowledgements First of all, I acknowledge the Darug, Tharawal, Cabrogal and Wiradjuri peoples as the traditional owners of the land on which this thesis has been written. Sovereignty was never ceded, and this has always been and always will be Aboriginal land. I want to sincerely thank my principal supervisor, Assoc. Prof. Diego Bubbio, for his priceless guidance over the last few years. He had the initial idea for this research project in 2015 and without his encouragement and advice I would have never had the opportunity to continue and complete my education in Australia. I also have to thank my co-supervisor, Prof. Dennis Schmidt, for his very precious support and for his tremendous insights. My sincere thanks also go to Dr. Chris Fleming and Assoc. Prof. Matt McGuire for having been part of my Confirmation of Candidature Committee. I also want to thank Assoc. Prof. Jennifer Mensch, Assoc. Prof. Dimitris Vardoulakis, Dr. Paul Alberts-Dezeew, and in general all the philosophy staff at the School of Humanities and Communication Arts of Western Sydney University, for having always been extremely friendly and available to me all the time. Special thanks also go to Dr. Wayne Peake for his immense patience and inestimable support for all the paperwork and administrative procedures I have had to complete. His help really made my life easier. Moreover, I wish to thank Prof. -

The Cabala and Its Influence on Judaism and Christianity. Bernhard Pick

10 $1.00 per Year JUNE, 1911 Price, Cents XTbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE 2>evoteb to tbe Science ot iRelfaion, tbe "Religion of Science, anb tbe Extension of tbe "Religious parliament loea Founded by Edward C. Hegeler. mw^^_ ft^* 9421.1' BUDDHA AS A FISHER OF MEN. (See page 357.) Zbc ©pen Court publishing Company CHICAGO LONDON: Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co., Ltd. Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., 5s. 6d). Entered as Second-Class Matter March 26, 1897, at the Post Office at Chicago, 111. under Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Company, 191 1. Price, 10 $1.00 per Year JUNE, 1911 Cents X^hc ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE Htevoteo to tbe Science ot iReliQion, tbe "Religion of Science, ano tbe Extension ot tbe "Religious parliament loea Founded by Edward C. Hegeler. %*M%1&<* %*t»5* *$2l'1j BUDDHA AS A FISHER OF MEN. (See page 357.) Gbe ©pen Court ffimbUsbing Company CHICAGO LONDON: Kegan Paul, Trench, Triibner & Co., Ltd. Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., 5s. 6d). Entered as Second-Class Matter March 26, 1897, at the Post Office at Chicago, 111. under Act of March 3, 1879. Copyright by The Open Court Publishing Company, 191 1. — VOL. XXV. (No. 6. JUNE, 1911. NO. 661 CONTENTS: PAGE Frontispiece. Buddha the Fisherman. The Cabala and Its Influence on Judaism and Christianity. Bernhard Pick. 321 The Fish in Brahmanism and Buddhism (Illustrated). Editor 343 Immediacy. Frederic Drew Bond 358 Evolution of the Divine. -

Franz Baader Und William Godwin Zum Einfluß Des Englischen Sozialismus in Der Deutschen Romantik

Klaus Peter Franz Baader und William Godwin Zum Einfluß des englischen Sozialismus in der deutschen Romantik Franz Baader, der Romantiker, hat früh begonnen und lange ge wirkt. Bereits in den 1780er Jahren, ungefähr zehn Jahre vor Friedrich Schlegel und Novalis, begann er sich mit Kant und Her der, mit Hemsterhuis, Lavater und Jacobi auseinanderzusetzen, mit der damaligen Moderne also, die er mit dem Katholizismus seiner Herkunft zu verbinden suchte. Der katholische Theologe Johann Michael Sailer in Ingolstadt, wo Baader Medizin studierte, und die Schriften des französischen Theosophen Louis Claude de St. Martin weckten in dieser Zeit auch bereits sein lebenslanges Interesse für die Tradition der Mystik. Und noch in den 1830er Jahren, ein halbes Jahrhundert später, durch Welten, so scheint es, von dem ausgehenden 18. Jahrhundert und der Frühromantik ge trennt, war er, der 1841 mit 76 Jahren starb, geistig aktiv und stellte sich den Auseinandersetzungen der Zeit. Wo sonst in der Romantik gibt es eine vergleichbare Spannweite der historischen Erfahrung und des Versuches, auf sie eingreifend zu reagieren? Die Romantiker haben ihn denn auch alle geschätzt und von ihm ge lernt, angefangen bei dem jungen Friedrich Schlegel bis hin zu dem späten Schelling. Wie bei keinem andern also ist bei Baader die Frage relevant nach dem Verhältnis von früh und spät, von Früh romantik und Spätromantik. Ich möchte mich hier auf nur einen Aspekt des umfangreichen und äußerst vielfältigen Werkes beschränken: auf Baaders Inter esse für soziale Fragen. Seine bekannteste Schrift auf diesem Ge biet ist der späte, 1835 erschienene Aufsatz mit dem barocken Titel: „Über das dermalige Mißverhältnis der Vermögenslosen oder Proletairs zu den Vermögen besitzenden Klassen der Sozietät in betreff ihres Auskommens, sowohl in materieller als in intellek tueller Hinsicht, aus dem Standpunkte des Rechts betrachtet". -

Jean-Claude Wolf/ Freiburg/Schweiz Das Böse Als Ethische Kategorie

28. April 2014 Universität Mainz Jean-Claude Wolf/ Freiburg/Schweiz Das Böse als ethische Kategorie Im ersten Teil dieser Problemübersicht werden Reduktionsversuche des Bösen behandelt. Es wurde bisher versucht, das Böse als Schwäche bzw. Mangel (1.1.), als Unwissenheit (1.2.), als Symptom von externen Faktoren wie Knappheit, Konkurrenzkampf, Geldwirtschaft und schlechten Einflüssen (1.3.) oder als Symptom von Verletzungen und Krankheit zu erklären. (1.4) Kausale Erklärungen stoßen aber immer wieder an Grenzen; es scheint so etwas wie ein irrationaler Rest, ein unerklärliches Mysterium des Bösen übrig zu bleiben. Während die Pathologisierung des Bösen reduktionistisch ist, schlagen Baader und Schelling vor, das Böse in Analogie zur Krankheit zu verstehen. Das analogische und symbolische Verstehen scheint eine grundsätzlich andere Sichtweise auf das Böse zu eröffnen. (2) Um zu verdeutlichen, dass kausale Erklärungen ihrer Intention oder Tendenz nach das Böse eliminieren, wird im zweiten Teil die symbolische Dimension des Bösen behandelt; sie ruft nicht nach Erklärung, sondern nach Deutung. Die Symbolik des Bösen macht aus der sog. säkularen Ethik eine „Tiefenethik“, indem sie die Ethik in einen größeren Sinn- und Bedeutungszusammenhang von Lebensprozessen einfügt, welche nicht nur die nüchterne Unterscheidung von Richtig und Falsch, Imperativen und Verboten, sondern auch den Umgang mit Hoffnungen und Ängsten, Gelingen und Scheitern betreffen. Zur Illustration dieser Symbolik dienen ausgewählte biblische Gestalten des Bösen wie der Teufel, Adam, Kain und Judas. Der Beitrag wird mit einem Ausblick auf das Begriffspaar Opfer/Täter abgerundet. (3) Festgefahrene Opfererzählungen lassen sich neu erzählen und verlieren damit eventuell etwas von ihrer Fatalität. 0. Einleitung Es gibt in der Aufklärung und Aufklärungstheologie (Neologie) eine Tendenz zur Reduktion des Bösen, parallel zur Abschaffung des Glaubens an den Satan, an ewige Höllenstrafen und an den Sündenfall bzw. -

PHILOSOPHICAL INVESTIGATIONS INTO the ESSENCE of HUMAN FREEDOM SUNY Series in Contemporary Continental Philosophy Dennis J

F.F. W.J.SchellingW.J.Schelling TranslatedTranslated and with an IntroductionIntroduction andand NotesNotes byby JeffJeff LoveLove and and JohannesJohannes SchmidtSchmidt PhilosophicalPhilosophical InvestigationsInvestigations intointo thethe EssenceEssence ofof HumanHuman FreedomFreedom PHILOSOPHICAL INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE ESSENCE OF HUMAN FREEDOM SUNY series in Contemporary Continental Philosophy Dennis J. Schmidt, editor PHILOSOPHICAL INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE ESSENCE OF HUMAN FREEDOM F. W. J. SCHELLING Translated and with an Introduction by Jeff Love and Johannes Schmidt STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2006 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 194 Washington Avenue, Suite 305, Albany, NY 12210-2384 Production by Michael Haggett Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schelling, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von, 1775–1854. [Philosophische Untersuchungen u(ber das Wesen der menschlichen Freiheit. English] Philosophical investigations into the essence of human freedom / F.W.J. Schelling ; translated and with an introduction by Jeff Love and Johannes Schmidt. p. cm. — (Suny series in contemporary continental philosophy) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-7914-6873-9 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-7914-6873-9 (hardcover : alk.