Observation of the Spring Night Sky Self-Guided Viewing Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

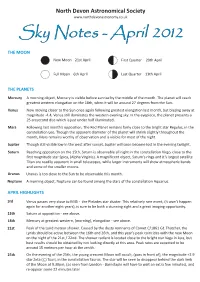

Sky Notes - April 2012

North Devon Astronomical Society www.northdevonastronomy.co.uk Sky Notes - April 2012 THE MOON New Moon 21s t April First Quarter 29th April Full Moon 6th April Last Quarter 13th April THE PLANETS Mercury A morning object, Mercury is visible before sunrise by the middle of the month. The planet will reach greatest western elongation on the 18th, when it will be around 27 degrees from the Sun. Venus Now moving closer to the Sun once again following greatest elongation last month, but blazing away at magnitude -4.4, Venus still dominates the western evening sky. In the eyepiece, the planet presents a 25 arcsecond disc which is just under half illuminated. Mars Following last month’s opposition, The Red Planet remains fairly close to the bright star Regulus, in the constellation Leo. Though the apparent diameter of the planet will shrink slightly throughout the month, Mars remains worthy of observation and is visible for most of the night. Jupiter Though still visible low in the west after sunset, Jupiter will soon become lost in the evening twilight. Saturn R eaching opposition on the 15th, Saturn is observable all night in the constellation Virgo, close to the first magnitude star Spica, (Alpha Virginis). A magnificent object, Saturn’s rings and it’s largest satellite Titan are readily apparent in small telescopes, while larger instruments will show atmospheric bands and some of the smaller moons. Uranus Ur anus is too close to the Sun to be observable this month. Neptune A morning object, Neptune can be found among the stars of the constellation Aquarius. -

Plotting Variable Stars on the H-R Diagram Activity

Pulsating Variable Stars and the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram The Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) Diagram: The H-R diagram is an important astronomical tool for understanding how stars evolve over time. Stellar evolution can not be studied by observing individual stars as most changes occur over millions and billions of years. Astrophysicists observe numerous stars at various stages in their evolutionary history to determine their changing properties and probable evolutionary tracks across the H-R diagram. The H-R diagram is a scatter graph of stars. When the absolute magnitude (MV) – intrinsic brightness – of stars is plotted against their surface temperature (stellar classification) the stars are not randomly distributed on the graph but are mostly restricted to a few well-defined regions. The stars within the same regions share a common set of characteristics. As the physical characteristics of a star change over its evolutionary history, its position on the H-R diagram The H-R Diagram changes also – so the H-R diagram can also be thought of as a graphical plot of stellar evolution. From the location of a star on the diagram, its luminosity, spectral type, color, temperature, mass, age, chemical composition and evolutionary history are known. Most stars are classified by surface temperature (spectral type) from hottest to coolest as follows: O B A F G K M. These categories are further subdivided into subclasses from hottest (0) to coolest (9). The hottest B stars are B0 and the coolest are B9, followed by spectral type A0. Each major spectral classification is characterized by its own unique spectra. -

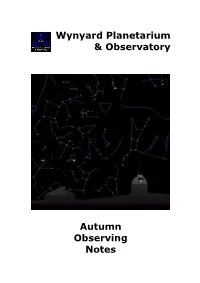

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory a Autumn Observing Notes

Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory A Autumn Observing Notes Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn Tour of the Sky with the Naked Eye CASSIOPEIA Look for the ‘W’ 4 shape 3 Polaris URSA MINOR Notice how the constellations swing around Polaris during the night Pherkad Kochab Is Kochab orange compared 2 to Polaris? Pointers Is Dubhe Dubhe yellowish compared to Merak? 1 Merak THE PLOUGH Figure 1: Sketch of the northern sky in autumn. © Rob Peeling, CaDAS, 2007 version 1.2 Wynyard Planetarium & Observatory PUBLIC OBSERVING – Autumn North 1. On leaving the planetarium, turn around and look northwards over the roof of the building. Close to the horizon is a group of stars like the outline of a saucepan with the handle stretching to your left. This is the Plough (also called the Big Dipper) and is part of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The two right-hand stars are called the Pointers. Can you tell that the higher of the two, Dubhe is slightly yellowish compared to the lower, Merak? Check with binoculars. Not all stars are white. The colour shows that Dubhe is cooler than Merak in the same way that red-hot is cooler than white- hot. 2. Use the Pointers to guide you upwards to the next bright star. This is Polaris, the Pole (or North) Star. Note that it is not the brightest star in the sky, a common misconception. Below and to the left are two prominent but fainter stars. These are Kochab and Pherkad, the Guardians of the Pole. Look carefully and you will notice that Kochab is slightly orange when compared to Polaris. -

134, December 2007

British Astronomical Association VARIABLE STAR SECTION CIRCULAR No 134, December 2007 Contents AB Andromedae Primary Minima ......................................... inside front cover From the Director ............................................................................................. 1 Recurrent Objects Programme and Long Term Polar Programme News............4 Eclipsing Binary News ..................................................................................... 5 Chart News ...................................................................................................... 7 CE Lyncis ......................................................................................................... 9 New Chart for CE and SV Lyncis ........................................................ 10 SV Lyncis Light Curves 1971-2007 ............................................................... 11 An Introduction to Measuring Variable Stars using a CCD Camera..............13 Cataclysmic Variables-Some Recent Experiences ........................................... 16 The UK Virtual Observatory ......................................................................... 18 A New Infrared Variable in Scutum ................................................................ 22 The Life and Times of Charles Frederick Butterworth, FRAS........................24 A Hard Day’s Night: Day-to-Day Photometry of Vega and Beta Lyrae.........28 Delta Cephei, 2007 ......................................................................................... 33 -

Appendix: Spectroscopy of Variable Stars

Appendix: Spectroscopy of Variable Stars As amateur astronomers gain ever-increasing access to professional tools, the science of spectroscopy of variable stars is now within reach of the experienced variable star observer. In this section we shall examine the basic tools used to perform spectroscopy and how to use the data collected in ways that augment our understanding of variable stars. Naturally, this section cannot cover every aspect of this vast subject, and we will concentrate just on the basics of this field so that the observer can come to grips with it. It will be noticed by experienced observers that variable stars often alter their spectral characteristics as they vary in light output. Cepheid variable stars can change from G types to F types during their periods of oscillation, and young variables can change from A to B types or vice versa. Spec troscopy enables observers to monitor these changes if their instrumentation is sensitive enough. However, this is not an easy field of study. It requires patience and dedication and access to resources that most amateurs do not possess. Nevertheless, it is an emerging field, and should the reader wish to get involved with this type of observation know that there are some excellent guides to variable star spectroscopy via the BAA and the AAVSO. Some of the workshops run by Robin Leadbeater of the BAA Variable Star section and others such as Christian Buil are a very good introduction to the field. © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 M. Griffiths, Observer’s Guide to Variable Stars, The Patrick Moore 291 Practical Astronomy Series, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00904-5 292 Appendix: Spectroscopy of Variable Stars Spectra, Spectroscopes and Image Acquisition What are spectra, and how are they observed? The spectra we see from stars is the result of the complete output in visible light of the star (in simple terms). -

Star Science in the Autumn Sky by John R

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 32 - Fall 1995 © 1995, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. Star Science in the Autumn Sky by John R. Percy, University of Toronto and George Musser, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Be honest: Do the stars all look the same to you? If you look up at the night sky, you can see anything from dozens to thousands of them, depending on where you live. To most people, the stars are just points of light, each one like the other. To astronomers, however, stars are as varied as people. There are as many different kinds of stars in our galaxy as there are people on Earth. They come in all shapes, sizes, colors, and dispositions. And stars, like people, have their life cycles. They are born, grow up, and die (don't pay taxes, though). The study of the stars and their lives, the great People magazine of the skies, is known as astrophysics. Astrophysics sounds imposing. Say the word at a cocktail party and see how fast the conversation grinds to a halt. Star science, which is what astrophysics is, sounds much more friendly. The following activities will introduce you to star science as you ramble across the autumn sky. Though the stars are distant, you can come to understand their nature by making simple observations and drawing analogies to everyday things on Earth. When you can look at a star and see more than a point of light, the night sky will come alive. Activity 1. Finding your way with a star map Activity 2. -

Variable Star

Variable star A variable star is a star whose brightness as seen from Earth (its apparent magnitude) fluctuates. This variation may be caused by a change in emitted light or by something partly blocking the light, so variable stars are classified as either: Intrinsic variables, whose luminosity actually changes; for example, because the star periodically swells and shrinks. Extrinsic variables, whose apparent changes in brightness are due to changes in the amount of their light that can reach Earth; for example, because the star has an orbiting companion that sometimes Trifid Nebula contains Cepheid variable stars eclipses it. Many, possibly most, stars have at least some variation in luminosity: the energy output of our Sun, for example, varies by about 0.1% over an 11-year solar cycle.[1] Contents Discovery Detecting variability Variable star observations Interpretation of observations Nomenclature Classification Intrinsic variable stars Pulsating variable stars Eruptive variable stars Cataclysmic or explosive variable stars Extrinsic variable stars Rotating variable stars Eclipsing binaries Planetary transits See also References External links Discovery An ancient Egyptian calendar of lucky and unlucky days composed some 3,200 years ago may be the oldest preserved historical document of the discovery of a variable star, the eclipsing binary Algol.[2][3][4] Of the modern astronomers, the first variable star was identified in 1638 when Johannes Holwarda noticed that Omicron Ceti (later named Mira) pulsated in a cycle taking 11 months; the star had previously been described as a nova by David Fabricius in 1596. This discovery, combined with supernovae observed in 1572 and 1604, proved that the starry sky was not eternally invariable as Aristotle and other ancient philosophers had taught. -

Pennsylvania Science Olympiad Southeast Regional Tournament 2013 Astronomy C Division Exam March 4, 2013

PENNSYLVANIA SCIENCE OLYMPIAD SOUTHEAST REGIONAL TOURNAMENT 2013 ASTRONOMY C DIVISION EXAM MARCH 4, 2013 SCHOOL:________________________________________ TEAM NUMBER:_________________ INSTRUCTIONS: 1. Turn in all exam materials at the end of this event. Missing exam materials will result in immediate disqualification of the team in question. There is an exam packet as well as a blank answer sheet. 2. You may separate the exam pages. You may write in the exam. 3. Only the answers provided on the answer page will be considered. Do not write outside the designated spaces for each answer. 4. Include school name and school code number at the bottom of the answer sheet. Indicate the names of the participants legibly at the bottom of the answer sheet. Be prepared to display your wristband to the supervisor when asked. 5. Each question is worth one point. Tiebreaker questions are indicated with a (T#) in which the number indicates the order of consultation in the event of a tie. Tiebreaker questions count toward the overall raw score, and are only used as tiebreakers when there is a tie. In such cases, (T1) will be examined first, then (T2), and so on until the tie is broken. There are 12 tiebreakers. 6. When the time is up, the time is up. Continuing to write after the time is up risks immediate disqualification. 7. In the BONUS box on the answer sheet, name the gentleman depicted on the cover for a bonus point. 8. As per the 2013 Division C Rules Manual, each team is permitted to bring “either two laptop computers OR two 3-ring binders of any size, or one binder and one laptop” and programmable calculators. -

Getting Started with Variable Star Observing

Getting Started with Variable Star Observing The primary types of variable stars you will be observing are: Cepheids - Named after Delta Cephei, these luminous stars brighten and fade with clockwork regularity. There are several types of Cepheids ranging from Beta Cepheids with 0.1 magnitude fluctuations and short periods from 3 to 7 hours to W Virginis Stars with fluctuation of about one magnitude over a period of up to 20 days. In 1910, Henrietta Leavitt learned that the longer a Cepheids period was, the brighter the absolute magnitude was. This led to Harlow Shapely developing the method of using Cepheids to determine the distance to globular clusters and nearby galaxies. Mira Stars - These long period variables are very large red pulsating stars having brightness magnitude ranges of up to 11 magnitudes and a time period from 24 days to 5.7 years. These stars can be regular, semiregular, or irregular. Some examples are Mira 2.0-9.3 332 days, R Leo 5.9 -10.1 313 days, Chi Cygni 3.3-14.2 408 days, Betelgeuse .4- 1.3 5.7 years. Estimates should be done at least twice per month. Eruptive Stars - This group contains Novae and Nova like stars with a great range of types. Recurrent Nova such as T Coronae Borealis may have outbursts that are decades apart. Stars like U Geminorum and SS Cygni repeat their outbursts every few months. One type, R Coronae Borealis, instead of erupting drops by as much as eight magnitudes. UV Ceti stars may flare several magnitudes in a matter of minutes. -

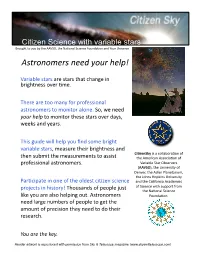

Astronomers Need Your Help!

Citizen Science with variable stars Brought to you by the AAVSO, the Naonal Science Foundaon and Your Universe Astronomers need your help! Variable stars are stars that change in brightness over 1me. There are too many for professional astronomers to monitor alone. So, we need your help to monitor these stars over days, weeks and years. This guide will help you find some bright variable stars, measure their brightness and Ci#zenSky is a collaboraon of then submit the measurements to assist the American Associaon of professional astronomers. Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), the University of Denver, the Adler Planetarium, the Johns Hopkins University Par1cipate in one of the oldest ci1zen science and the California Academies projects in history! Thousands of people just of Science with support from the Naonal Science like you are also helping out. Astronomers Foundaon. need large numbers of people to get the amount of precision they need to do their research. You are the key. Header artwork is reproduced with permission from Sky & Telescope magazine (www.skyandtelescope.com) This is a Light Curve It shows how a star’s brightness changes over 1me. Light curves are a fundamental tool for variable star astronomy. They are relavely simple and easy to grasp. They are simply a graph of brightness (Y axis) vs. 1me (X axis). Brightness increases as you go up the graph and 1me advances as you move to the right. The brightness of a star is measured in units of “magnitude”. No1ce that the magnitude scale on the graph above shows smaller numbers as the star gets brighter and larger numbers as the star gets fainter. -

Radial Velocity Observations of Classical Pulsating Stars

Radial Velocity Observations of Classical Pulsating Stars Richard I. Anderson1 1. European Southern Observatory Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, D-85748 Garching b. Munchen,¨ Germany I concisely review the history, applications, and recent developments pertaining to radial velocity (RV) observations of classical pulsating stars. The focus lies on type-I (classical) Cepheids, although the historical overview and most tech- nical aspects are also relevant for RR Lyrae stars and type-II Cepheids. The presence and impact of velocity gradients and different experimental setups on measured RV variability curves are discussed in some detail. Among the recent developments, modulated spectral line variability results in modulated RV curves that represent an issue for Baade-Wesselink-type distances and the detectability of spectroscopic companions, as well as challenges for stellar models. Spectral line asymmetry (e.g. via the bisector inverse span; BIS) provides a useful tool for identifying modulated spectral variability due to perturbations of velocity gradients. The imminent increase in number of pulsating stars observed with time series RVs by Gaia and ever increasing RV zero-point stability hold great promise for high-precision velocimetry to continue to provide new insights into stellar pulsations and their interactions with atmospheres. 1 Introduction Classical pulsating stars such as RR Lyrae stars and type-I & II Cepheids feature radial pulsations that manifest as periodic spectral variability. Radial velocity (RV) observations reduce the complexity of spectral variability (in Teff , log g, turbulence, velocity gradients, line asymmetries, among others) to a series of easy-to-interpret 1 Doppler shifts in units of km s− . Although RVs are convenient quantities to work with, their seeming simplicity can be misleading. -

Small Wonders: Cepheus a Monthly Sky Guide for the Beginning to Intermediate Amateur Astronomer Tom Trusock 11-Sep-2005

Small Wonders: Cepheus A monthly sky guide for the beginning to intermediate amateur astronomer Tom Trusock 11-Sep-2005 Figure 1. W idefield map 2/11 Small Wonders: Cepheus Target List Object Type Size Mag RA Dec µ (mu) Cephei (Garnet star) Star 4.2 21h 43m 42.2s +58° 48' 27" KR 60 Star 9.6 22h 28m 14.4s +57° 43' 37" IC 1396 Reflection Nebula 90.0' 21h 39m 17.8s +57° 31' 38" NGC 40 Planetary Nebula 1.2' 12.3 00h 13m 21.7s +72° 33' 12" NGC 188 Open Cluster 15.0' 8.1 00h 48m 10.8s +85° 17' 04" NGC 6939 Open Cluster 10.0' 7.8 20h 31m 38.0s +60° 41' 00" NGC 6951 Galaxy 3.9'x3.2' 11 20h 37m 19.6s +66° 07' 39" NGC 7023 Bright Nebula 10.0'x8.0' 7.1 21h 01m 41.3s +68° 11' 36" NGC 7354 Planetary Nebula 36" 12.2 22h 40m 34.1s +61° 18' 59" NGC 7510 Open Cluster 7.0' 7.9 23h 11m 19.7s +60° 36' 07" Challenge Objects Object Type Size Mag RA Dec Sh2-155 Bright Nebula 50.0'x30.0' 22h 57m 02.9s +62° 38' 51" Cepheus ur celestial personality for the month – Cepheus – is the son of Belus, King of Eqypt. Cepheus became King of Ethiopia and entered celestial mythology as both the husband of O Cassiopiea and the father of Andromeda. According to one legend, both Cepheus and Cassiopiea are killed at Andromeda‘s wedding to Peresus. Poseidon then places both in the night sky to immortalize them.