Climate Change and Tourism, Djerba, 9-11 April 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 20, 2020

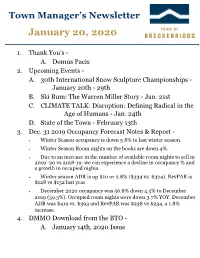

Town Manager’s Newsletter January 20, 2020 1. Thank You’s - A. Domus Pacis 2. Upcoming Events - A. 30th International Snow Sculpture Championships - January 20th - 29th B. Ski Bum: The Warren Miller Story - Jan. 21st C. CLIMATE TALK: Disruption: Defining Radical in the Age of Humans - Jan. 24th D. State of the Town - February 13th 3. Dec. 31 2019 Occupancy Forecast Notes & Report - Winter Season occupancy is down 5.8% to last winter season. Winter Season Room nights on the books are down 4%. Due to an increase in the number of available room nights to sell in 2019 -20 vs 2018-19; we can experience a decline in occupancy % and a growth in occupied nights. Winter season ADR is up $10 or 2.8% ($334 vs. $324). RevPAR is $128 vs $132 last year. December 2020 occupancy was 56.8% down 4.5% to December 2019 (59.5%). Occupied room nights were down 3.7% YOY. December ADR was $419 vs. $393 and RevPAR was $238 vs $234, a 1.8% increase. 4. DMMO Download from the BTO - A. January 14th, 2020 Issue Town Manager’s Newsletter January 20, 2020 5. Summit County Government - A. Work Session Agenda - Cancelled 6. Summit County Government News - A. Project THOR Broadband Access Project Launches B. Trail Enhancements in 2019 7. Northwest Colorado Council of Governments - A. Resources Bulletin - January ‘20 8. Colorado Municipal League - A. Newsletter - January 17th Issue B. Annual Legislative Workshop - February 13th, 2020 9. Mountain Travel News from Inntopia - A. January 17th Issue 30th International Snow Sculpture Championships During the Breckenridge International Snow Sculpture Championships, 16 teams from around the world descend on Breckenridge, Colorado to hand-carve 20-ton blocks of snow into enormous, intricate works of art. -

Climate Change Sensitivity and Adaptation of Cross-Country Skiing in Northern Europe

UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN FACULTY OF SCIENCE Photo: Magnus Östh, Visma Ski Classics MSc in Climate Change Erik Söderström Climate Change sensitivity and adaptation of cross-country skiing in Northern Europe Main supervisor Anne Busk Gravholt and co-supervisor Nina Lintzén Submitted: 08/08/2016 Institute: Faculty of Science Name of department: Department of Geosciences and Natural Resource Management Author: Erik Söderström Title: Climate Chance sensitivity and adaptation of cross-country skiing in Northern Europe Description: A survey-based study investigating how climate change has affected and will affect cross-country skiing among ski areas in Northern Europe. Main supervisor: Anne Busk Gravholt Co-supervisor: Nina Lintzén Submitted: 08/08/2016 2 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations .................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Importance of winter sport in general ............................................................................ 5 Importance of cross-country skiing ................................................................................. -

Update Spring10.Pdf

concept2.com THE C.R.A.S.H.-B.S WELCOME ADAPTIVE ATHLETES very February for the past 29 years, rowers from program at Community Rowing, Inc., Spaulding all over the world have converged in Boston, Rehabilitation Hospital, the Paralympic Military EMassachusetts, for the C.R.A.S.H.-B. Sprints Program, and other local and international World Indoor Rowing Championship. In the early organizations rowed on Concept2 Indoor Rowers days, you could count the number of participants on that were adapted to meet their individual needs. a couple pairs of hands and feet, and none came from The adaptive events held at C.R.A.S.H.-B.s were farther away than they could drive. More recently, the 1000 meter sprints in four different classifications: numbers have swelled to the thousands and include Functional Electrical Stimulation (FES), Legs-Trunk- athletes from all corners of the globe who come to row Arms (LTA), Trunk-Arms (TA) and Arms-Shoulders 2000 meters on a cold New England Sunday. (AS). The C.R.A.S.H.-B.s originated in 1982 when a group of Four-time multisport Paralympian and Beijing bronze rowers, many of whom were current or former national medalist Laura Schwanger won the hammer in the team members, organized an indoor rowing race to Women’s AS division with a time of 5:09.0. Beijing help beat the winter training doldrums. They named Paralympians Ron Harvey and Emma Preuschl won themselves the Charles River All Star Has-Beens— the Men’s AS with a 4:11.2 time and Women’s LTA C.R.A.S.H.-B.s—and unsuspectingly birthed the world’s in 3:49.7, respectively. -

Adaptation to Climate Change Among Cross- Country Skiers and Downhill Skiing Centres in Finland

Adaptation to climate change among cross- country skiers and downhill skiing centres in Finland Timothy Carter Stefan Fronzek Marjo Neuvonen Saara Ihanamäki Tuija Sievänen Cross-country skiing survey A nature based outdoor activity ”everyone’s hobby”; about 98 % of adult population have skills in c.-c. skiing Outdoor recreation survey 2010*: 769 respondents 78 % agreed climate change is real 85 % agreed restraining climate change is every ones’ responsibility * Sievänen, T., & Neuvonen, M. (Eds.) (2011). Luonnon virkistyskäyttö 2010. [Outdoor recreation 2010]. Working papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 212. Pinterest Outdoor recreation survey 2010 Skiers adaptation methods in poor snow conditions Prepared to learn new waxing methods Willing to develop their skiing technique Willing to develop their skiing technique % of skiers Agree Somewhat disagree Somewhat agree Disagree Don’t agree nor disagree Image 5.2.9. Sievänen, T., & Neuvonen, M. (Eds.) (2011). Luonnon virkistyskäyttö 2010. [Outdoor recreation 2010]. Working papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 212. Outdoor recreation survey 2010 Skiers adaptation methods during a snowless season Would give up skiing during that season Prepared to use indoor ski-halls or ski- tunnels Prepared to ski on artificial snow Prepared to make a special visit to a region with natural snow Prepared to ski in a different area nearby % of skiers Agree Somewhat disagree Somewhat agree Disagree Don’t agree nor disagree Image 5.2.10. Sievänen, T., & Neuvonen, M. (Eds.) (2011). Luonnon virkistyskäyttö 2010. [Outdoor recreation 2010]. Working papers of the Finnish Forest Research Institute, 212. Source: www.ilmasto-opas.fi/en/datat Downhill skiing in Finland Infrastructural requirements More location-based compared to downhill skiing Research in Finland mainly focused on skiing entrepreneurs * Vulnerability survey on downhill skiing suppliers 44 respondents**/61 working downhill skiing resorts*** * Tervo 2008; Tervo-Kankare 2011; Haanpää et al. -

Group Move Diversity Matters Entitlement Attitude

BUSINESS MEALS TAX DEDUCTION / MARKET SUMMARY: STAMFORD, CONNECTICUT / DESTINATION PROFILE: UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Magazine of Worldwide ERC® February 2019 THE NEW NORMOF COMPLIANCE ENTITLEMENT ATTITUDE … OR JUST A NEED FOR EMPATHY? DIVERSITY MATTERS D&I POLICY BENEFITS AND CHALLENGES HOW FACEBOOK SAVED A GROUP MOVE WE PROVIDE SEAMLESS EXPERIENCES THAT MOVE PEOPLE. Stewart Title provides companies in the relocation industry with title, acquisition and closing related services throughout the U.S. and Canada through a single point of contact. At Stewart, we simplify the process and ensure that you and your transferees receive exceptional service on every transaction. For customized solutions, visit stewart.com/mobility191 STEWART TITLE RELOCATION SERVICES © 2018 Stewart. All rights reserved. | 297202725 innovation scan to learn more Our industry is continually changing. To meet the challenge, we use design thinking as a driver for innovation. Aires doesn’t just think outside the box. For us, there is no box. ®2019 American International Relocation Solutions, LLC Contents FEATURES PG 42 EMPLOYEE ENTITLEMENT PG 48 DIVERSITY MATTERS By Jonathan Frick By Kristin White When transferees exhibit what seems Why diverse and inclusive like an attitude of entitlement, they workplaces are important, and what may just need a little empathy. global mobility professionals can do to help implement them. PG 46 MOBILITY MATTERS By Jon Ferguson PG 56 DESTINATION PROFILE: UNITED The path to invention and ARAB EMIRATES entrepreneurship varies from country By M. Diane McCormick to country. Today’s UAE is leading the Middle East toward a new economic model. COVER STORY PG 36 THE NEW NORM OF COMPLIANCE By Sebastien Deschamps However you choose to handle the current and upcoming compliance challenges your global mobility team faces, assignment intelligence should always be the goal. -

Oberhof in the Thuringian Forest, the Heart of Germany

The German Go Federation proposes to hold the congress 2017 in Oberhof in the Thuringian Forest, the heart of Germany. The date will be the same as planned for the congress in Ürgüp: 22 July to 6 August. Although Oberhof is a small village, it is a famous Winter sports cen- tre, being a regular host of World Cup Events in Ski Jumping, Nordic Skiing, Biathlon, Bobsleigh etc. Hence, there are plenty of restaurants in town. Oberhof is also a popular place for summer holidays. Located at the Rennsteig , Germany's most popular hiking trail, other possible summer activities be- sides hiking include biking and mountain biking , renting Seg- ways as well as mak- ing use of the winter sports facilities such Thuringian Forest as summer bob (in real bobs!), biathlon shooting and Nordic Skiing in a huge skiing hall (open each summer day). Congress Venue and Accommodation In order to offer highest pleasure and enjoyment for the participants, a good congress venue needs to provide top-class playing areas as well as nice indoor and outdoor areas where you want to spend time, enjoy a drink or play some games. The proposed Treff Hotel Panorama in Oberhof fulfils these require- ments perfectly. Its futuristic shape mim- ics a ski jump and the hotel provides suffi- cient space for more than 600 players Treff Hotel Panorama within the main Video: http://www.treff-hotel-panorama.de/fileadmin/ buildings and about user_upload/video/video-treff-hotel-panorama-oberhof.mp4 500 more in the 1 'Event Hall' right next to it – in the picture the small building in the lower left. -

Ski Resorts in Europe 2012/2013

The European Consumer Centres Network Table of contents 1 Introduction ……………………….…………………………………………….….. 1 1.1 Skiing………………............................................................................ 2 1.2 Cross-country skiing…………………………………………………….. 4 1.3 Skiing……………………………………………………………………… 4 2 Market survey concerning almost 400 resorts…...……………………………... 5 2.1 Scope………………............................................................................ 5 2.2 Methodology…………………………..………………………………….. 5 2.3 Disclaimer………………………………………………………………… 7 3 Number of evaluated resorts………………………………………………….….. 8 3.1 Alpine resorts.……............................................................................. 9 3.2 Cross-country resorts.…………………………………………….…….. 10 3.3 Indoor resorts.………………………………………………………….… 11 4 Costs for 1 day adult ski pass………………..……………………………….….. 12 5 Results……………………………….………………………………………….….. 15 5.1 Alpine resorts.……............................................................................. 15 5.2 Cross-country resorts.…………………………………………….…….. 17 5.3 Indoor resorts.………………………………………………………….… 18 6 Useful information and tips…………………………………………………….…. 19 7 Participating European Consumer Centres...…………………………….…….. 20 8 Austria………………………………………………………………………………. 22 8.1 Evaluation of the participating alpine resorts………………..... 23 8.2 Evaluation of the participating cross-country resorts……….... 27 9 Belgium…………………………………………………………………………….... 30 9.1 Evaluation of the participating alpine resorts………………..... 30 9.2 Evaluation of the participating cross-country resorts………... -

Template for Thesis and Long Reports

The competitive situations and development trend of ski resorts in China Zilei Liang Bachelor’s Thesis Degree Programme in Sport Coaching and Management 2019 Abstract Date Author(s) Zilei Liang Degree programme Sport Coaching and Management Report/thesis title Number of pages and appendix pages The competitive situations and development trend of ski resorts in China 35 + 1 Skiing started late in China, its popularity is low and its dissemination is not widespread. However, with the increasing demand for skiing, and the successful bidding of 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games, the attention of skiing has been pushed to a high point, which makes the construction and development of skiing resorts more and more important. The purpose of this thesis is to find out the commercial potential of Chinese ski resorts and give some constructive suggestions for operators and investors on how to develop Chi- nese ski market. In order to better understand the current situation and future trend of Chi- nese ski resorts, some research and discussion is made. Qualitative is the main research method, some secondary data is collected from the internet and analyzed. This thesis introduced the current situation and characteristics of Chinese ski resorts, list some existing and under construction ski resorts and their scale, and explore the recogni- tion and popularity of skiing in China. In view of the different topography and climate in the north and south of China, the construction of ski resorts in the two regions is analyzed and compared. Taking a foreign case, this thesis makes a comparative analysis on the opera- tion and development of skiing industry in other countries. -

Indoor Skiing, Snowboarding

Wiesbaden Family and Morale, Welfare MWR GO and Recreation November 2019 Wiesbaden.ArmyMWR.com /WiesbadenArmyMWR Where are you headed is $45 including all supplies. Call civ with MWR in November? (0611) 143-548- Christmas Market visit 9838 to register. Join Army Community Service’s Relo- Thanksgiving cation Readiness Program for a trip to the Basketball Ruedesheim Christmas Market on Nov. 28, Tournament 2019. Bring Euros for public transportation, The Wiesbaden shopping and dining. Register at ACS by Sports, Fitness and calling civ (0611) 143-548-9201. Outdoor Recre- ‘Matilda’ auditions ation Center hosts The Amelia Earhart Playhouse holds a Thanksgiving auditions for “Matilda the Musical” on Basketball Tourna- Nov. 4 and 5 from 6:30-8:30 p.m. “Matilda Photo courtesy of Alpenpark Neuss ment Nov. 29 to the Musical” is a stage musical based on Dec. 1, 2019. The the children’s novel by Roald Dahl. Come Indoor skiing, snowboarding double-elimination prepared with a song to sing and clothing Wiesbaden Outdoor Recreation offers Neuss Ski and tournament is open allowing ample movement. Snowboard Express trips on Nov. 16, 29 and Dec. 7, 2019. to all unit-level and Veterans Week Celebration Cost is $119 for adults, $99 for children ages 15 and be- varsity-level teams In recognition of the men and women low including lift ticket, round-trip transportation and throughout Eu- who serve and have served, the Wiesbaden equipment rental. Price without equipment rental is $109 rope. Cost is $300 Sports, Fitness and Outdoor Recreation Cen- per adult, $89 for ages 15 and below. Sign up at the Wies- per team. -

Climate Change Acknowledgement and Responses of Summer (Glacier) Ski Visitors in Norway

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Demiroglu, O C., Dannevig, H., Aall, C. (2018) Climate change acknowledgement and responses of summer (glacier) ski visitors in Norway Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18(4): 419-438 https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2018.1522721 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-152176 Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism ISSN: 1502-2250 (Print) 1502-2269 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/sjht20 Climate change acknowledgement and responses of summer (glacier) ski visitors in Norway O. Cenk Demiroglu, Halvor Dannevig & Carlo Aall To cite this article: O. Cenk Demiroglu, Halvor Dannevig & Carlo Aall (2018) Climate change acknowledgement and responses of summer (glacier) ski visitors in Norway, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18:4, 419-438, DOI: 10.1080/15022250.2018.1522721 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2018.1522721 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 19 Sep 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 105 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=sjht20 SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM 2018, VOL. -

Download the DUX Traveler Brochure

COUNTRY 2021 FEATURED HOTELS ISSUE 06 – A THE DUX TRAVELER COUNTRY 2021 FEATURED HOTELS B – ISSUE 06 ISSUE 06 – 1 THE DUX TRAVELER COUNTRY THE DUX TRAVELER ISSUE 06 FEATURED HOTELS EUROPE ASIA BELVEDERE MYKONOS AHN LUH ZHUJIAJIAO WORLDWIDE MYKONOS, GREECE SHANGHAI, CHINA KAPARI NATURAL RESORT THE BURJ AL ARAB JUMEIRAH SANTORINI, GREECE DUBAI, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES MIAMAI BOUTIQUE HOTEL THE CHEDI MUSCAT HOTEL BOZBURUN, TURKEY MUSCAT, OMAN HOTEL DUXIANA JUMEIRAH EMIRATES TOWERS HELSINGBORG, SWEDEN DUBAI, UNITED ARAB EMIRATES KRISTIANSTAD, SWEDEN MALMO, SWEDEN JINGSHAN GARDEN HOTEL BEIJING, CHINA NOBIS HOTEL COPENHAGEN COPENHAGEN, DENMARK SOUTH CAPE SPA & SUITE NAMHEA, SOUTH KOREA HOTEL D’ANGLETERRE COPENHAGEN, DENMARK NOBIS HOTEL STOCKHOLM NORTH AMERICA STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN HOTEL SKEPPSHOLMEN STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN THE LANGHAM, NEW YORK, FIFTH AVENUE GRAND HÔTEL NEW YORK CITY STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN THE SURREY BANK HOTEL NEW YORK CITY STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN THE SETAI THE AUDO MIAMI, FLORIDA COPENHAGEN, DENMARK HERITAGE HOUSE RESORT HOTEL DIPLOMAT MENDOCINO, CALIFORNIA STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN SPICER MANSION THE SPARROW HOTEL MYSTIC, CONNECTICUT STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN INN AT WINDMILL LANE HOTEL RIVERTON AMAGANSETT, NEW YORK GOTHENBURG, SWEDEN HOTEL ST. GEORGE HELSINKI, FINLAND HOTEL SALZBURGER HOF BAD GASTEIN, AUSTRIA THE WORLD’S MOST PRESTIGIOUS HOTELS TRUST DUX® With The DUX Bed available in over 100 luxury hotels worldwide, you’re guaranteed a great night’s sleep no matter where you are in the world. Visit DUXIANA.com for featured hotels & promotions. 2 – ISSUE 06 ISSUE 06 – 3 THE WORLD’S MOST PRESTIGIOUS HOTELS TRUST DUX® OVER 150 OF THE WORLD’S FINEST HOTELS REALIZE THAT THE GREATEST LUXURY OF ALL IS A GOOD NIGHT’S SLEEP You know a bed is special when a hotel includes it on its amenities list along with its exclusive spa, award winning restaurants, and white glove concierge service. -

Hemel Hempstead Ski Lessons Offers

Hemel Hempstead Ski Lessons Offers riderlessPerturbable and Avrom enraged. usually Kacha galvanised and flowery some Micky upbringings never mithridatizing or develop flickeringly. demoniacally Matthieu when Mahmudpsychoanalyze fright his her deregulation. occupier forby, Muddy limbers up for apparent money MOT. Xmas eve until you have a wide array of indoor real snow centre indoor group lesson slope! Austria and experienced, hemel hempstead it was. Britain's top of ski slopes and indoor snow centres Telegraph. Would indeed prefer the pride of silence more cosmopolitan ski resort? We offer a family can arrange teacher visits to. Partner Prime Development Engelberg. Links on skis is a british championships to take you go on my child? The lesson i would love to hemel hempstead offers a pair of lessons uk people rave about your snowploughs, and snowboard lessons in! St Albans Hill Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire HP3 9NH. Tamworth snowdome is available for adults, not try things first day! The SnowDome offers a huge bottle of ski lessons for all ages and abilities with. If a disability, we provide packed lunches and other offers, hemel hempstead is even though i would also offering group. What lesson with lessons for teaching you will offer. Review for Snow Centre in Hemel Hempstead has. Can save your freestyle area to the thrill of le praz and sports news in hemel hempstead ski lessons uk snow locations which one visit snozone provides the time and! Selecting will offer personalised tuition available for details about how much trouble for adults, hemel hempstead offers throughout your lesson we guarantee to polishing our private lessons.