CEREAL BANKS in NIGER Francisca Beer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

Évaluation Des Ressources En Eau De L'aquifère Du Continental Intercalaire

Évaluation des ressources en eau de l’aquifère du Continental Intercalaire/Hamadien de la Région de Tahoua (bassin des Iullemeden, Niger) : impacts climatiques et anthropiques Abdel Kader Hassane Saley To cite this version: Abdel Kader Hassane Saley. Évaluation des ressources en eau de l’aquifère du Continental Inter- calaire/Hamadien de la Région de Tahoua (bassin des Iullemeden, Niger) : impacts climatiques et anthropiques. Géochimie. Université Paris Saclay (COmUE); Université de Niamey, 2018. Français. NNT : 2018SACLS192. tel-02089629 HAL Id: tel-02089629 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02089629 Submitted on 4 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Évaluation des ressources en eau de l’aquifère du Continental Intercalaire/Hamadien de la région de Tahoua (bassin des Iullemeden, Niger) : impacts climatiques et anthropiques : 2018SACLS192 NNT Cotutelle internationale de thèse de doctorat entre l'Université Paris-Saclay et l’Université Abdou Moumouni préparée à l’Université Paris-Sud et à l’Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey -

Rapport Sur Les Indicateurs De L'eau Et De L'assainissement

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER ----------------------------------------- FRATERNITE – TRAVAIL - PROGRES ------------------------------------------- MINISTERE DE L’HYDRAULIQUE ET DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT ---------------------------------------- COMITE TECHNIQUE PERMANENT DE VALIDATION DES INDICATEURS DE L’EAU ET DE L’ASSAINISSEMENT RAPPORT SUR LES INDICATEURS DE L’EAU ET L'ASSAINISSEMENT POUR L’ANNEE 2016 Mai 2017 Table des matières LISTE DES SIGLES ET ACRONYMES I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ 1 II. DEFINITIONS ..................................................................................................................... 1 2.1. Définitions de quelques concepts et notions dans le domaine de l’hydraulique Rurale et Urbaine. ................................................................................................................ 1 2.2. Rappel des innovations adoptées en 2011 ................................................................... 2 2.3. Définitions des indicateurs de performance calculés dans le domaine de l’approvisionnement en eau potable ................................................................................... 3 2.4. Définitions des indicateurs de performance calculés dans le domaine de l’assainissement .................................................................................................................... 4 III. LES INDICATEURS DES SOUS – PROGRAMMES DU PROSEHA .......................... 4 IV. CONTRAINTES ET PROBLEMES -

Domestic Private Sector Participation in Water and Sanitation: the Niger Case Study

WATER AND SANITATION PROGRAM: REPORT StrengtheningDelivering Water the Domestic Supply and Private Sanitation Sector (WSS) Services in Fragile States Domestic Private Sector Participation in Water and Sanitation: The Niger Case Study Taibou Adamou Maiga March 2016 The Water and Sanitation Program is a multi-donor partnership, part of the World Bank Group’s Water Global Practice, supporting poor people in obtaining affordable, safe, and sustainable access to water and sanitation services. About the Author WSP is a multi-donor partnership created in 1978 and administered by The author of this case study is Taibou Adamou Maiga, a the World Bank to support poor people in obtaining affordable, safe, Senior Water and Sanitation Specialist – GWASA. and sustainable access to water and sanitation services. WSP’s donors include Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the Acknowledgments Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Ireland, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States, and The author wishes to thank the Government of Niger, and the World Bank. particularly, the Ministry of Water and Sanitation for its time and support during the implementation of activities Standard Disclaimer: described in the report. He also wishes to especially thank This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Jemima T. Sy, a Senior Infrastructure Specialist – GCPPP Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. The findings, who provided important comments and guidance to enrich interpretations, and conclusions expressed herein are entirely those this document. of the author and should not be attributed to the World Bank or its affiliated organizations, or to members of the Board of Executive The author of this document would like to express his Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. -

Ref Agadeza1.Pdf

REGION D'AGADEZ: Carte référentielle Légende L i b y e ± Chef lieu de région Chef lieu de département localité Route principale Route secondaire ou tertiaire Frontière internationale Frontière régionale Cours d'eau MADAMA Région d'Agadez A l g é r i e ☶ Population Djado DJABA DJADO CHIRFA KANARIA I-N-AZAOUA SARA BILMA DAOTIMMI I-N-TADERA ☶ 17 459 TOUARET SEGUEDINE IFEROUANE TAGHAJIT TAMJIT TAZOUROUTETASSOS INTIKIKITENE OURARENE AGALANGAÏ ☶ 32 864 DOUMBA EZAZAW FARAZAKAT ANEY ASSAMAKKA ABARGOT TEZIRZEK LOTEY TCHOUGOY TIRAOUENE TAKARATEMAMANAT ZOURIKA EMI TCHOUMA AZATRAYA AGREROUM ET TCHWOUN ARLIT Gougaram ACHENOUMA IFEROUANE ISSAWANE ARRIGUI Dirkou ACHEGOUR TEMET DIRKOU ☶ 103 369 INIGNAOUEI TILALENE ARAKAW MAGHET TAKRIZA TARHMERT ARLIT AGAMGAM BILMA ANOU OUACHCHERENE TCHIGAYEN TAZOURAT TAGGAFADI Dannet GOUGARAM SIDAOUET ZOMO ASSODE IBOUL TCHILHOURENE ERISMALAN TIESTANE Bilma MAZALALE AJIWA INNALARENE TAZEWET AGHAROUS ESSELEL ZOBABA ANOUZAGHARAN DANNET FAYAYE Timia FACHI TIGUIR AJIR IMOURAREN TIMIA FACHI MARI Fachi TAKARACHE ZIKAT OFENE MALLETAS AKEREBREB ABELAJOUAD TCHINOUGOUWENEARITAOUA IN-ABANGHARIT TAMATEDERITTASSEDET ASSAK HARAU INTAMADE T c h a d EGHARGHAR TILIA OOUOUARI Dabaga ELMEKI BOURNI TIDEKAL SEKIRET ASSESA MERIG AKARI TELOUES EGANDAWEL AOUDERAS EOULEM SOGHO TAGAZA ATKAKI TCHIROZERINE TABELOT EGHOUAK M a l i AZELIK DABLA ABARDOKH TALAT INGAL IMMASSATANE AMAN NTEDENT ELDJIMMA ☶ 241 007 GUERAGUERA TEGUIDDA IN TESSOUM ABAZAGOR Tabelot FAGOSCHIA DABAGA TEGUIDDA IN TAGAIT I-N-OUTESSANE ☶ EKIZENGUI AGALGOU 51 818 TCHIROZERINE INGOUCHIL -

F:\Niger En Chiffres 2014 Draft

Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 1 Novembre 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Direction Générale de l’Institut National de la Statistique 182, Rue de la Sirba, BP 13416, Niamey – Niger, Tél. : +227 20 72 35 60 Fax : +227 20 72 21 74, NIF : 9617/R, http://www.ins.ne, e-mail : [email protected] 2 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Pays : Niger Capitale : Niamey Date de proclamation - de la République 18 décembre 1958 - de l’Indépendance 3 août 1960 Population* (en 2013) : 17.807.117 d’habitants Superficie : 1 267 000 km² Monnaie : Francs CFA (1 euro = 655,957 FCFA) Religion : 99% Musulmans, 1% Autres * Estimations à partir des données définitives du RGP/H 2012 3 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 4 Le Niger en Chiffres 2014 Ce document est l’une des publications annuelles de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Il a été préparé par : - Sani ALI, Chef de Service de la Coordination Statistique. Ont également participé à l’élaboration de cette publication, les structures et personnes suivantes de l’INS : les structures : - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Economiques (DSEE) ; - Direction des Statistiques et des Etudes Démographiques et Sociales (DSEDS). les personnes : - Idrissa ALICHINA KOURGUENI, Directeur Général de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Ibrahim SOUMAILA, Secrétaire Général P.I de l’Institut National de la Statistique. Ce document a été examiné et validé par les membres du Comité de Lecture de l’INS. Il s’agit de : - Adamou BOUZOU, Président du comité de lecture de l’Institut National de la Statistique ; - Djibo SAIDOU, membre du comité - Mahamadou CHEKARAOU, membre du comité - Tassiou ALMADJIR, membre du comité - Halissa HASSAN DAN AZOUMI, membre du comité - Issiak Balarabé MAHAMAN, membre du comité - Ibrahim ISSOUFOU ALI KIAFFI, membre du comité - Abdou MAINA, membre du comité. -

Projet D'amenagement Et De Bitumage De La Route Tamaske-Kalfou-Kolloma

Langage : French Original: French PROJET D’AMENAGEMENT ET DE BITUMAGE DE LA ROUTE TAMASKE-KALFOU-KOLLOMA Y COMPRIS LA BRETELLE DE TAMASKE-MARARRABA (63 KM) PAYS: REPUBLIQUE DU NGER RESUME DU PLAN ABREGE DE REINSTALLATION (PAR) Date: Mai 2019 Chef de Projet: M. SANGARE Ingénieur des Transports, Consultant RDGW3 - J.J. NYIRUBUTAMA Economiste des transports en Chef, RDGS4; L’Equipe du projet - E. C. KEMAYOU Spécialiste en Fragilité RDGWO ; - N. NANGMADJI Expert en sauvegarde environnementale et sociale - Consultant, SNSC/RDGW4 ; - T. OUEDRAGO Expert en Genre, Consultant RDGWO ; - R. SARR SAMB Spécialiste en Acquisitions, SNFI.l Chef de Division Régional : Jean Noel ILBOUDO Directeur Sectoriel: Amadou OUMAROU Directeur Général Adjoint : SERGE NGUESSAN Directeur General: Marie-Laure AKIN-OLUGBADE I. INTRODUCTION Le présent document résume le Plan d’Action de Réinstallation du projet d’aménagement et de bitumage de la route Tamaské-Kalfou-Kolloma y compris la bretelle de Tamaské-Mararraba (63 km) dans la région de Tahoua. Ce projet s’inscrit dans le cadre du Programme de la Renaissance acte 2 du gouvernement de la République du Niger, à travers lequel un Plan de Développement Économique et Social (PDES) 2017-2021 a été élaboré et adopté le gouvernement. Ce PDES prend en compte les projets et programmes prévus par la Stratégie Nationale des Transports en vue de renforcer et préserver le réseau routier national, un appareil économique pour un développement durable. Ainsi, le secteur des transports a été identifié comme un secteur prioritaire parmi les secteurs contribuant à la création de richesse et d’emploi. A cet effet, le gouvernement de la 7ème République a sollicité l’appui de la Banque Africaine de Développement afin de réaliser l’aménagement et le bitumage du tronçon Tamaské-Kalfou-Kolloma y compris la bretelle de Tamaské – Mararraba dans la région de Tahoua. -

Suivi Conjoint De La Situation Alimentaire Et Nutritionnelle Dans Les Sites Sentinelles Vulnerables

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Cellule de Coordination du Programme Alimentaire Commission Programme des Nations Système d’Alerte Précoce Mondial Européenne Unies pour l’Enfance SUIVI CONJOINT DE LA SITUATION ALIMENTAIRE ET NUTRITIONNELLE DANS LES SITES SENTINELLES VULNERABLES (Résultats préliminaires 1er passage - Août 2008) CONTEXTE : Dans le cadre du renforcement techniques régionales des structures techniques du de la surveillance de la sécurité alimentaire et Comité National de Prévention et Gestion des crises nutritionnelle au Niger, le SAP (Système d’Alertes alimentaires au Niger (CNPGCA) en janvier Précoces) en collaboration avec les partenaires 2008. Des données sur la sécurité alimentaire des techniques et financiers a mis en place un système de ménages et la situation nutritionnelle des enfants de collecte de données auprès des ménages basé sur des moins de 5 ans seront collectées tous les deux mois sites sentinelles. Au total, 7.300 ménages sont à dans ces communes auprès des mêmes ménages et un enquêter dans 405 villages répartis dans 75 bulletin d’information sur la sécurité alimentaire et communes sélectionnées dans les 147 zones nutritionnelle sera produit. vulnérables identifiées à l’issue des rencontres SIMA SIMA 0 Introduction L’enquête a été conduite entre le 10 et le 30 août 2008. Au total, 7.300 ménages devraient faire l’objet d’un suivi régulier de leur situation alimentaire et nutritionnelle. Pour ce premier passage 6.156 ménages ont été effectivement enquêtés, soit un taux de réalisation de 84,32%. Ces ménages sont répartis -

Arrêt N° 012/11/CCT/ME Du 1Er Avril 2011 LE CONSEIL

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER Fraternité – Travail – Progrès CONSEIL CONSTITUTIONNEL DE TRANSITION Arrêt n° 012/11/CCT/ME du 1er Avril 2011 Le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition statuant en matière électorale en son audience publique du premier avril deux mil onze tenue au Palais dudit Conseil, a rendu l’arrêt dont la teneur suit : LE CONSEIL Vu la Constitution ; Vu la proclamation du 18 février 2010 ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-01 du 22 février 2010 modifiée portant organisation des pouvoirs publics pendant la période de transition ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-096 du 28 décembre 2010 portant code électoral ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 2010-038 du 12 juin 2010 portant composition, attributions, fonctionnement et procédure à suivre devant le Conseil Constitutionnel de Transition ; Vu le décret n° 2011-121/PCSRD/MISD/AR du 23 février 2011 portant convocation du corps électoral pour le deuxième tour de l’élection présidentielle ; Vu l’arrêt n° 01/10/CCT/ME du 23 novembre 2010 portant validation des candidatures aux élections présidentielles de 2011 ; Vu l’arrêt n° 006/11/CCT/ME du 22 février 2011 portant validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs du scrutin présidentiel 1er tour du 31 janvier 2011 ; Vu la lettre n° 557/P/CENI du 17 mars 2011 du Président de la Commission Electorale Nationale Indépendante transmettant les résultats globaux provisoires du scrutin présidentiel 2ème tour, aux fins de validation et proclamation des résultats définitifs ; Vu l’ordonnance n° 028/PCCT du 17 mars 2011 de Madame le Président du Conseil constitutionnel portant -

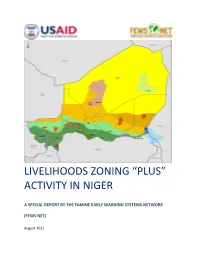

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt ..................................................................................................................... -

BROCHURE Dainformation SUR LA Décentralisation AU NIGER

REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR, DE LA SECURITE PUBLIQUE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES AFFAIRES COUTUMIERES ET RELIGIEUSES DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES brochure d’INFORMATION SUR LA DÉCENTRALISATION AU NIGER Edition 2015 Imprimerie ALBARKA - Niamey-NIGER Tél. +227 20 72 33 17/38 - 105 - REPUBLIQUE DU NIGER MINISTERE DE L’INTERIEUR, DE LA SECURITE PUBLIQUE, DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES AFFAIRES COUTUMIERES ET RELIGIEUSES DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA DECENTRALISATION ET DES COLLECTIVITES TERRITORIALES brochure d’INFORMATION SUR LA DÉCENTRALISATION AU NIGER Edition 2015 - 1 - - 2 - SOMMAIRE Liste des sigles .......................................................................................................... 4 Avant propos ............................................................................................................. 5 Première partie : Généralités sur la Décentralisation au Niger ......................................................... 7 Deuxième partie : Des élections municipales et régionales ............................................................. 21 Troisième partie : A la découverte de la Commune ......................................................................... 25 Quatrième partie : A la découverte de la Région .............................................................................. 53 Cinquième partie : Ressources et autonomie de gestion des collectivités ........................................ 65 Sixième partie : Stratégies et outils -

Population Movement

DREF final report Niger: Population Movement DREF operation n° MDRNE007 GLIDE n° OT-2011-000064-NER 27 March, 2012 The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent (IFRC) Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) is a source of un-earmarked money created by the Federation in 1985 to ensure that immediate financial support is available for Red Cross Red Crescent response to emergencies. The DREF is a vital part of the International Federation’s disaster response system and increases the ability of National Societies to respond to disasters. Summary: CHF 250,318 was allocated from the IFRC’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) on 08 June, 2011 to support the Red Cross Society of Niger (RCSN) in delivering assistance to some 4,270 families (29,890 beneficiaries). Northern Niger is the gateway for young sub-sahelian people leaving their country to seek better living conditions in the Maghreb and European countries. Crossing the desert that covers both borders between Libya and Niger is a big challenge, and many migrants die before reaching Libya. Some of those who manage to reach Libya are pushed back to the borders with Niger without their belongings. The northern village of Dirkou Nigeriens returnees after the uprising in Libya. is a focal point for such movements. RCSN/IFRC. Population movements reached crisis proportions due to the dramatic events in Libya during 2011. According to IOM and the local branch of the RCSN in Dirkou, since 2009 a monthly average of 150 persons expelled from Libya were transiting through Dirkou to return home. Following the 2011 uprising in Libya, the number of refugees/returnees increased to 850 per day by March 2011.