A Dream Play and the Ghost Sonata – in Connection with Sigmund Freud's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meaning in Movement: Adaptation and the Xiqu Body in Intercultural Chinese Theatre

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Articles Arts and Sciences Spring 2014 Meaning in Movement: Adaptation and the Xiqu Body in Intercultural Chinese Theatre Emily E. Wilcox William & Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/aspubs Part of the Chinese Studies Commons, and the Dance Commons Recommended Citation Wilcox, Emily E., Meaning in Movement: Adaptation and the Xiqu Body in Intercultural Chinese Theatre (2014). TDR: The Drama Review, 58(1), 42-63. https://doi.org/10.1162/DRAM_a_00327 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Articles by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meaning in Movement Adaptation and the Xiqu Body in Intercultural Chinese Theatre Emily E. Wilcox Strindberg Rewritten “You don’t know what to do? Let me tell you. Let me show you!”1 Jean yells this at Julie as he gives a villainous laugh and tosses his ankle-length silk sleeves into the air. Jean rushes toward Julie, grabs what we now know is an imaginary bird from Julie’s hand and, facing the audience, violently wrings the bird’s neck, killing it. The bird still in his hand, Jean bends both legs into a deep squat, spins his arms like a jet propeller in a fanshen2 turn, and then bashes the bird’s body into the stage floor. Julie screams. Jean lets out a violent shout, whips his sleeves toward the floor and struts away offstage in a wide-legged swagger.3 1. -

"Infidelity" As an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) As a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888)

"Infidelity" as an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). مسـرحيــة After Miss Julie للكاتب البريطاني باتريك ماربر كإعادة إبداع لمسرحية Miss Julie للكاتب السويدي أوجست ستريندبرج Dr. Reda Shehata associate professor Department of English - Zagazig University د. رضا شحاته أستاذ مساعد بقسم اللغة اﻹنجليزية كلية اﻵداب - جامعة الزقازيق "Infidelity" as an "Act of Love" Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) "Infidelity" as an "Act of Love": Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a Rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). Abstract Depending on Linda Hutcheon's notion of adaptation as "a creative and interpretative act of appropriation" and David Lane's concept of the updated "context of the story world in which the characters are placed," this paper undertakes a critical examination of Patrick Marber's After Miss Julie (1995) as a creative rewrite of August Strindberg's Miss Julie (1888). The play appears to be both a faithful adaptation and appropriation of its model, reflecting "matches" for certain features of it and "mismatches" for others. So in spite of Marber's different language, his adjustment of the "temporal and spatial dimensions" of the original, and his several additions and omissions, he retains the same theme, characters, and—to a considerable extent, plot. To some extent, he manages to stick to his master's brand of Naturalism by retaining the special form of conflict upon which the action is based. In addition to its depiction of the failure of post-war class system, it shows strong relevancy to the spirit of the 1990s, both in its implicit critique of some aspects of feminism (especially its call for gender equality) and its bold address of the masculine concerns of that period. -

Violin Concerto Miss Julie Suite • Fanfare for a Joyful Occasion Lorraine Mcaslan, Violin Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra David Lloyd-Jones

570705 bk Alwyn 26/1/11 12:18 Page 8 Also available: ALWYN Violin Concerto Miss Julie Suite • Fanfare for a Joyful Occasion Lorraine McAslan, Violin Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra David Lloyd-Jones 8.570704 8.557645 8.570705 8 570705 bk Alwyn 26/1/11 12:18 Page 2 William Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra is Britain’s oldest surviving professional symphony orchestra, dating ALWYN from 1840. Vasily Petrenko was appointed Principal Conductor of the orchestra in September 2006 and in (1905-1985) September 2009 became Chief Conductor until 2015. The orchestra gives over sixty concerts each season in Liverpool Philharmonic Hall and in recent seasons world première performances have included major works by Sir Violin Concerto 36:57 John Tavener, Karl Jenkins, Michael Nyman and Jennifer Higdon, alongside works by Liverpool-born composers John McCabe, Emily Howard, Mark Simpson and Kenneth Hesketh. The orchestra also tours widely throughout the 1 Allegro ma non troppo 18:27 United Kingdom and has given concerts in the United States, the Far East and throughout Europe. In 2009 the 2 Allegretto e semplice 9:30 orchestra won the Ensemble of the Year award in the 20th Royal Philharmonic Society Music Awards, the most 3 Allegro moderato alla marcia – Allegro e pesante – prestigious accolade for live classical music-making in the United Kingdom. Recent additions to the orchestra’s extensive discography include Tchaikovsky’s Manfred Symphony [Naxos 8.570568] (2009 Classic Allegro molto 9:00 FM/Gramophone Orchestral Recording of the Year), Sir John Tavener’s Requiem, Volumes 1–4 of the Shostakovich symphony cycle and Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances and Piano Concertos Nos. -

Romantic and Realistic Impulses in the Dramas of August Strindberg

Romantic and realistic impulses in the dramas of August Strindberg Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Dinken, Barney Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 13:12:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557865 ROMANTIC AND REALISTIC IMPULSES IN THE DRAMAS OF AUGUST STRINDBERG by Barney Michael Dinken A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF DRAMA In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 1 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fu lfillm e n t of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available,to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests fo r permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judg ment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholar ship, In a ll other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Directing an Immersive Adaptation of Strindberg's a Dream Play

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses October 2018 Interpreting Dreams: Directing an Immersive Adaptation of Strindberg's A Dream Play Mary-Corinne Miller University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Dramatic Literature, Criticism and Theory Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, Performance Studies Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Mary-Corinne, "Interpreting Dreams: Directing an Immersive Adaptation of Strindberg's A Dream Play" (2018). Masters Theses. 730. https://doi.org/10.7275/12087874 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/730 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTERPRETING DREAMS: DIRECTING AN IMMERSIVE ADAPTATION OF STRINDBERG’S A DREAM PLAY A Thesis Presented By MARY CORINNE MILLER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS September 2018 Department of Theater © Copyright by Mary Corinne Miller 2018 All Rights Reserved INTERPRETING DREAMS: DIRECTING AN IMMERSIVE ADAPTATION OF STRINDBERG’S A DREAM PLAY A Thesis Presented By MARY CORINNE MILLER Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________ Gina Kaufmann, Chair ____________________________________ Harley Erdman, Member ____________________________________ Gilbert McCauley, Member ____________________________________ Amy Altadonna, Member ____________________________ Gina Kaufmann, Department Head Department of Theater DEDICATION To my son, Everett You are my dream come true. -

Miss Julie by August Strindberg

MTC Education Teachers’ Notes 2016 Miss Julie by August Strindberg – PART A – 16 April – 21 May Southbank Theatre, The Sumner Notes prepared by Meg Upton 1 Teachers’ Notes for Miss Julie PART A – CONTEXTS AND CONVERSATIONS Theatre can be defined as a performative art form, culturally situated, ephemeral and temporary in nature, presented to an audience in a particular time, particular cultural context and in a particular location – Anthony Jackson (2007). Because theatre is an ephemeral art form – here in one moment, gone in the next – and contemporary theatre making has become more complex, Part A of the Miss Julie Teachers’ Notes offers teachers and students a rich and detailed introduction to the play in order to prepare for seeing the MTC production – possibly only once. Welcome to our new two-part Teachers’ Notes. In this first part of the resource we offer you ways to think about the world of the play, playwright, structure, theatrical styles, stagecraft, contexts – historical, cultural, social, philosophical, and political, characters, and previous productions. These are prompts only. We encourage you to read the play – the original translation in the first instance and then the new adaptation when it is available on the first day of rehearsal. Just before the production opens in April, Part B of the education resource will be available, providing images, interviews, and detailed analysis questions that relate to the Unit 3 performance analysis task. Why are you studying Miss Julie? The extract below from the Theatre Studies Study Design is a reminder of the Key Knowledge required and the Key Skills you need to demonstrate in your analysis of the play. -

Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation

Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation Strindberg on International Stages/ Strindberg in Translation Edited by Roland Lysell Strindberg on International Stages/Strindberg in Translation, Edited by Roland Lysell This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Roland Lysell and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5440-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5440-5 CONTENTS Contributors ............................................................................................... vii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Section I The Theatrical Ideas of August Strindberg Reflected in His Plays ........... 11 Katerina Petrovska–Kuzmanova Stockholm University Strindberg Corpus: Content and Possibilities ........ 21 Kristina Nilsson Björkenstam, Sofia Gustafsson-Vapková and Mats Wirén The Legacy of Strindberg Translations: Le Plaidoyer d'un fou as a Case in Point ....................................................................................... 41 Alexander Künzli and Gunnel Engwall Metatheatrical -

Preliminary Pages

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known, including display on the world wide web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis. Signature: Leesa Haspel April 14, 2010 Becoming Miss Julie: A Study in Practical Dramaturgy by Leesa Haspel Adviser Donald McManus Department of Theater Studies Donald McManus Adviser Lisa Paulsen Committee Member Joseph Skibell Committee Member April 14, 2010 Becoming Miss Julie: A Study in Practical Dramaturgy By Leesa Haspel Adviser Donald McManus An abstract of A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Emory College of Arts and Sciences of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Department of Theater Studies 2010 Abstract Becoming Miss Julie: A Study in Practical Dramaturgy By Leesa Haspel This paper serves to document and reflect upon an actor’s experience using research to inform and develop a role. Theater Emory’s 2009 production of Miss Julie serves as the case study, describing the process of creating the titular role. An overview of the history of dramaturgy, a dramaturgical protocol, exploration of relevant acting styles, analysis of the Theater Emory production, and personal reflection on the experience of developing Miss Julie cohere to create a guide advocating the use of practical dramaturgy in contemporary acting. -

A Fire in Her Mind: Medicine, Gender Identity, and Strindberg's Miss Julie

A Fire in Her Mind: Medicine, Gender Identity, and Strindberg’s Miss Julie A Research Community Proposal for the LARC grant, Summer 2016 Jonathan Cole Monique Bourque Mary Rose Branick Will Forkin Victoria Mohtes-Chan Jesse Sanchez Community Proposal A Fire in Her Mind: Medicine, Gender Identity, and Strindberg’s Miss Julie This LARC group will examine some of the biggest questions that underlie modernity: the nature of human nature, the role of “the natural” and scientific/medical authority in dictating and defining normal behavior, particularly in regard to sexuality; and the emergence of psychiatry as one of the human sciences. These emerging scientific ideas found an immediate home in nineteenth-century experimental theatre. Theatre artists, tired of the contrived plotlines and moralist, one- dimensional characters of the Melodrama, began to turn to the emerging tenets of behaviorism, genetics, and Social Darwinism in order to bring experiments in human behavior to the stage. Led by European artists-thinkers like Emile Zola, Andre Antoine, Otto Brahm, Henrik Ibsen and August Strindberg, experimental theatre strove to create a theatre praxis that utilized the theatre as an experiment: a way to observe human behavior. This artistic movement, loosely organized under the mantle of “Naturalism,” birthed Strindberg’s greatest work, Miss Julie. While the play itself fails as a piece of Naturalist theatre, Strindberg’s obsession with the inner workings of the human mind, with behavior, with heredity, bloodline, sexuality and fealty/fidelity created in Jean and Julie two of the most fascinating characters in theatre literature. These characters are inexorably linked to Strindberg’s understanding of the science of the time. -

UBC Opera2020/21 SEASON

UBC Opera 2020/21 SEASON presents Il viaggio a Reims (The Journey to Reims) Sung in Italian with English surtitles Dramma giocoso in One Act Music by Gioachino Rossini | Libretto by Luigi Balocchi October 16, 17, 18 at 7:30 pm Performed at the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts and streamed live to your location! Conductor – David Agler Director – Nancy Hermiston Lighting Design – Jeremy Baxter Costume Design – Parvin Mirhady Technical Director – Grant Windsor JAN 30, 31 / FEB 2, 3, 5, 6, 2021 MAY 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 2021 UBC Opera Ensemble Old Auditorium Old Auditorium Pianists – Tina Chang (October 16, 18), Richard Epp (October 17) Mansfield Park Le nozze di Figaro There will be no intermission during the approximately 100-minute performance. Chamber Opera in Two Acts Comic Opera in Four Acts This production is made possible by the Sung in English with English surtitles Sung in Italian with English surtitles David Spencer Endowment Encouragement Fund Jonathan Dove Composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Composer Alasdair Middleton Librettist Lorenzo da Ponte Librettist We acknowledge that the University of British Columbia is situated on the traditional, ancestral and unceded territory of the Musqueam people. Nancy Hermiston Director Nancy Hermiston Director David Agler Conductor David Agler Conductor More information at ubcopera.com A Message from the Director Dear UBC Opera Ensemble Supporters and Audience Members, These are extraordinary times for all of us, and nothing Repairs have already begun and as heartbreaking as this damage is, it could have in life seems simple anymore. Indeed, producing opera been much worse. In all likelihood, it will be anywhere from four to seven weeks in this COVID-19 pandemic is not an easy task, but before we can have full access to the theatre. -

Introduction "Preface" to Miss Julie (1893)

Introduction August Strindberg (1849-1912) was a Swedish playwright. In his preface to Miss Julie, Strindberg speculates about bringing radical change to the theatre. "Preface" to Miss Julie (1893) As far as the scenery is concerned, I have borrowed from impressionistic painting its asymmetry, its quality of abruptness, and have thereby in my opinion strengthened the illusion. Because the whole room and all its contents are not shown, there is a chance to guess at things—that is, our imagination is stirred into complementing our vision. I have made a further gain in getting rid of those tiresome exits by means of doors, especially as stage doors are made of canvas and swing back and forth at the lightest touch. They are not even capable of expressing the anger of an irate pater familias who, on leaving his home after a poor dinner, slams the door behind him "so that it shakes the whole house." (On the stage the house sways.) I have also contented myself with a single setting, and for the double purpose of making the figures become parts of their surroundings, and of breaking with the tendency toward luxurious scenery. But having only a single setting, one may demand to have it real. Yet nothing is more difficult than to get a room that looks something like a room, although, the painter can easily enough produce waterfalls and flaming volcanoes. Let it go at canvas for the walls, but we might be done with the painting of shelves and kitchen utensils on the canvas. We have so much else on the stage that is conventional, and in which we are asked to believe, that we might at least be spared the too great effort of believing in painted pans and kettles. -

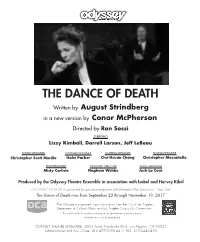

THE DANCE of DEATH Written by August Strindberg in a New Version by Conor Mcpherson Directed by Ron Sossi

THE DANCE OF DEATH Written by August Strindberg in a new version by Conor McPherson Directed by Ron Sossi STARRING Lizzy Kimball, Darrell Larson, Jeff LeBeau SCENIC DESIGNER COSTUME DESIGNER LIGHTING DESIGNER SOUND DESIGNER Christopher Scott Murillo Halei Parker Chu-Hsuan Chang Christopher Moscatiello PROP DESIGNER ASSISTANT DIRECTOR STAGE MANAGER Misty Carlisle Nagham Wehbe Josh La Cour Produced by the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble in association with Isabel and Harvey Kibel THE DANCE OF DEATH is presented by special arrangement with Dramatists Play Service Inc., New York The Dance of Death runs from September 23 through November 19, 2017 The Odyssey is supported in part by a grant from the City of Los Angeles, Department of Cultural Affairs, and Los Angeles County Arts Commission The video and/or audio recording of this performance by any means whatsoever is strictly prohibited. ODYSSEY THEATRE ENSEMBLE: 2055 South Sepulveda Blvd., Los Angeles, CA 90025 Administration and Box Office: 310-477-2055 ext 2 FAX: 310-444-0455 CAST (in order of appearance) THE CAPTAIN .................................................................Darrell Larson ALICE .............................................................................Lizzy Kimball KURT .................................................................................Jeff LeBeau SETTING An Island Fortress near a port in Sweden, Early 20th Century Running time: Two hours There will be one fifteen-minute intermission. This production is dedicated to Sam Shepard. A NOTE FROM THE DIRECTOR The Dance of Death has amazing significance to the whole world of contemporary drama. The "trapped" nature of its characters feels like Sartre's No Exit (and its classic line "Hell is other people"). And its foreshadow- ing of Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf is uncannily prescient, almost as if Albee "channeled" Strindberg in cooking up his own mixture of raucous verbal battle and deadly humor.