INTERVIEW with HERMAN H. LACKNER Interviewed by Betty J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pittsfield Building 55 E

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Pittsfield Building 55 E. Washington Preliminary Landmarkrecommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, December 12, 2001 CITY OFCHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Departmentof Planning and Developement Alicia Mazur Berg, Commissioner Cover: On the right, the Pittsfield Building, as seen from Michigan Avenue, looking west. The Pittsfield Building's trademark is its interior lobbies and atrium, seen in the upper and lower left. In the center, an advertisement announcing the building's construction and leasing, c. 1927. Above: The Pittsfield Building, located at 55 E. Washington Street, is a 38-story steel-frame skyscraper with a rectangular 21-story base that covers the entire building lot-approximately 162 feet on Washington Street and 120 feet on Wabash Avenue. The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. It is responsible for recommending to the City Council that individual buildings, sites, objects, or entire districts be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The Comm ission is staffed by the Chicago Department of Planning and Development, 33 N. LaSalle St., Room 1600, Chicago, IL 60602; (312-744-3200) phone; (312 744-2958) TTY; (312-744-9 140) fax; web site, http ://www.cityofchicago.org/ landmarks. This Preliminary Summary ofInformation is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation proceedings. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. PRELIMINARY SUMMARY OF INFORMATION SUBMITIED TO THE COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS IN DECEMBER 2001 PITTSFIELD BUILDING 55 E. -

333 North Michigan Buildi·N·G- 333 N

PRELIMINARY STAFF SUfv1MARY OF INFORMATION 333 North Michigan Buildi·n·g- 333 N. Michigan Avenue Submitted to the Conwnission on Chicago Landmarks in June 1986. Rec:ornmended to the City Council on April I, 1987. CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development J.F. Boyle, Jr., Commissioner 333 NORTH MICIDGAN BUILDING 333 N. Michigan Ave. (1928; Holabird & Roche/Holabird & Root) The 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING is one of the city's most outstanding Art Deco-style skyscrapers. It is one of four buildings surrounding the Michigan A venue Bridge that defines one of the city' s-and nation' s-finest urban spaces. The building's base is sheathed in polished granite, in shades of black and purple. Its upper stories, which are set back in dramatic fashion to correspond to the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, are clad in buff-colored limestone and dark terra cotta. The building's prominence is heightened by its unique site. Due to the jog of Michigan Avenue at the bridge, the building is visible the length of North Michigan Avenue, appearing to be located in the center of the street. ABOVE: The 333 North Michigan Building was one of the first skyscrapers to take advantage of the city's 1923 zoning ordinance, which encouraged the construction of buildings with setback towers. This photograph was taken from the cupola of the London Guarantee Building. COVER: A 1933 illustration, looking south on Michigan Avenue. At left: the 333 North Michigan Building; at right the Wrigley Building. 333 NORTH MICHIGAN BUILDING 333 North Michigan Avenue Architect: Holabird and Roche/Holabird and Root Date of Construction: 1928 0e- ~ 1QQ 2 00 Cft T Dramatically sited where Michigan Avenue crosses the Chicago River are four build ings that collectively illustrate the profound stylistic changes that occurred in American architecture during the decade of the 1920s. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany†

International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. Consequently, planners should tap into public’s digital engagement in city places to improve tourism and economy. Keywords: Social media, Iconic socio-spatial clusters, Popular places, Skyscrapers 1. Introduction 1.1. Sustainability: A Theoretical Framework The concept of sustainability continues to be of para- mount importance to our cities (Godschalk & Rouse, 2015). Planners, architects, economists, environmentalists, and politicians continue to use the term in their conver- sations and writings. -

Social Media and Popular Places: the Case of Chicago

CTBUH Research Paper ctbuh.org/papers Title: Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Author: Kheir Al-Kodmany, University of Illinois at Chicago Subjects: Keyword: Social Media Publication Date: 2019 Original Publication: International Journal of High-Rise Buildings Volume 8 Number 2 Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Kheir Al-Kodmany International Journal of High-Rise Buildings International Journal of June 2019, Vol 8, No 2, 125-136 High-Rise Buildings https://doi.org/10.21022/IJHRB.2019.8.2.125 www.ctbuh-korea.org/ijhrb/index.php Social Media and Popular Places: The Case of Chicago Kheir Al-Kodmany† Department of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Illinois at Chicago, USA Abstract This paper offers new ways to learn about popular places in the city. Using locational data from Social Media platforms platforms, including Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, along with participatory field visits and combining insights from architecture and urban design literature, this study reveals popular socio-spatial clusters in the City of Chicago. Locational data of photographs were visualized by using Geographic Information Systems and helped in producing heat maps that showed the spatial distribution of posted photographs. Geo-intensity of photographs illustrated areas that are most popularly visited in the city. The study’s results indicate that the city’s skyscrapers along open spaces are major elements of image formation. Findings also elucidate that Social Media plays an important role in promoting places; and thereby, sustaining a greater interest and stream of visitors. -

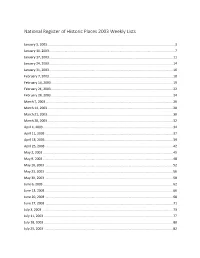

National Register of Historic Places Weekly Lists for 2003

National Register of Historic Places 2003 Weekly Lists January 3, 2003 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 January 10, 2003 ........................................................................................................................................... 7 January 17, 2003 ......................................................................................................................................... 11 January 24, 2003 ......................................................................................................................................... 14 January 31, 2003 ......................................................................................................................................... 16 February 7, 2003 ......................................................................................................................................... 18 February 14, 2003 ....................................................................................................................................... 19 February 21, 2003 ....................................................................................................................................... 22 February 28, 2003 ....................................................................................................................................... 24 March 7, 2003 ............................................................................................................................................ -

PRESERVATION CHICAGO the New York Life Insurance Building

2 0 0 6 PRESERVATION CHICAGO Chicago’s Seven Most Threatened Buildings The New York Life Insurance Building Address: 39 South LaSalle Street Date: 1894 Architect: William Lebaron Jenney Style: Chicago School Skyscraper CHRS Rating: Orange National Register: Not Listed Overview: George Orwell said in Animal Farm that all animals are equal, except some animals are more equal than others. The same could be argued that in Chicago, depending on how much clout one has, some Landmarks are more equal than others. Based on some recent proposals for downtown skyscraper projects, a separate and unequal set of standards has revealed itself regarding how the Commission on Chicago Landmarks considers changes to existing Landmarked buildings and Landmark Districts. Case in point is the current redevelopment plan proposed for the New York Life Building, one of William LeBaron Jenney’s seminal early skyscrapers. History: William LeBaron Jenney revolutionized world architecture with the development of the first skyscraper, the Home Insurance Building in Chicago in 1884. His pioneering use of the steel skeleton frame, rather than the thick heavy masonry bearing walls that were then the norm, set the standard for modern high-rise construction that is still in use today. With the demolition of the Home Insurance Building in 1931, the New York Life Building became the last remaining example of Jenney’s early steel frame skyscraper construction and is the closest link with the ground-breaking technology of Jenney’s Home Insurance Building. Furthermore, the role of Chicago as the “insurance broker to the West” cannot be understated, and this building serves as a key link to that history. -

MINUTES of the MEETING COMMISSION on CHICAGO LANDMARKS October 6, 2016

MINUTES OF THE MEETING COMMISSION ON CHICAGO LANDMARKS October 6, 2016 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks held its regularly scheduled meeting on October 6, 2016. The meeting was held at City Hall, 121 North LaSalle Street, Room 201-A, Chicago, Illinois. The meeting began at 12:49 p.m. PHYSICALLY PRESENT: Jim Houlihan, Vice Chairman David Reifman, Secretary, Commissioner of the Department of Planning and Development Gabriel Dziekiewicz Carmen Rossi Richard Tolliver Ernest Wong ABSENT: Rafael Leon, Chairman Juan Moreno Mary Ann Smith ALSO PHYSICALLY PRESENT: Dijana Cuvalo, Architect IV, Department of Planning and Development Lisa Misher, Department of Law, Real Estate Division Members of the Public (The list of those in attendance is on file at the Commission office.) A recording of this meeting is on file at the Department of Planning and Development/Planning, Design and Historic Preservation Division offices and is part of the public record of the regular meeting of the Commission on Chicago Landmarks. Vice Chairman Houlihan called the meeting to order. 1. Approval of the Minutes of Previous Meeting Regular Meeting of September 1, 2016 Motioned by Tolliver, seconded by Dziekiewicz. Approved unanimously (6-0). 2. Report from Public Hearing and Final Landmark Recommendation UPTOWN SQUARE DISTRICT WARD 46 Properties generally fronting on West Lawrence Avenue from North Magnolia Avenue to east of North Sheridan Road, and on North Broadway between West Wilson Avenue and West Gunnison Street, and on North Racine Avenue between West Leland Avenue and West Lawrence Avenue, and on West Leland Avenue between North Racine Avenue and North Winthrop Avenue Commissioner Rossi presented the Hearing Officer’s report. -

Typologies and Evaluation of Outdoor Public Spaces at Street Level of Tall Buildings in Chicago

TYPOLOGIES AND EVALUATION OF OUTDOOR PUBLIC SPACES AT STREET LEVEL OF TALL BUILDINGS IN CHICAGO Abstract Authors Zahida Khan and Peng Du Outdoor public spaces are key to human interactions, promoting Illinois Institute of Technology public life in cities. The constant increase in world population has led Keywords to increased tall urban conditions making the study of outdoor public Public spaces, tall buildings, urban forms, rating system spaces around tall buildings very popular. This paper outlines typol- ogies for outdoor public spaces occurring at street level of tall build- ings in downtown Chicago, the birthplace of skyscrapers and an ideal case study for an American city. The study uses online data archives, Google Maps, and on-site surveys as research techniques for the analysis. The result depicts around 50% of all the tall buildings in Chicago foster public life at its street level through public spaces. The other key finding is the outline of seven typologies based on their position around the tall building. Further, a comparative analysis is conducted using one example of each typology based on three crite- ria adopted from ‘Project for Public Spaces,’ namely (1) Accessibility; (2) Design and Comfort, and (3) Users and Activities. Prometheus 04 Buildings, Cities, and Performance, II Introduction outdoor public spaces, including: (A) Accessibility, (B) Design & Comfort, (C) Users & Activities, (D) Environ- Outdoor public spaces at street level of tall buildings play mental Sustainability, and (E) Sociable. The scope of this a significant role in sustainable city development. The research is limited to the first three design criteria since rapid increase in world population and constant growth of the last two require a bigger timeframe and is addressed urbanization has led many scholars to support Koolhaas’ for future research. -

Introduction 2019-2022 Doormen Agreement.Pub

FOR ABOMA MEMBER USE ONLY Issued November 2019 Apartment Building Owners and Managers Association of Illinois COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT BY AND BETWEEN APARTMENT BUILDING OWNERS AND MANAGERS ASSOCIATION OF ILLINOIS and SERVICE EMPLOYEES INTERNATIONAL UNION, LOCAL 1 PROPERTY SERVICE DIVISION for the period DECEMBER 1, 2019 THROUGH NOVEMBER 30, 2022 Covering Doorstaff, Receiving Room Employees and Others as defined in Article I INTRODUCTION This booklet is exclusively for the use of ABOMA Members and contains the following: • Pages 1 through 27 Full Collective Bargaining Agreement by and between ABOMA and SEIU Local 1, Property Service Division Covering Doorstaff Receiving Room Employees and Others as defined in Article I for the period of December 1, 2019 through November 30, 2022 • Page 24 Letter of Agreement – Drug and Alcohol Policies • Page 25 Letter of Agreement – Subcontracting • Page 26 and 27 Memorandum of Agreement relating to Sub contracting and sample of Contractor DSMOA SCHEDULE A Pages 1-3 (NIPF) The Buildings (Employers) identified in Schedule A of this Agreement shall contribute for all regular Employees to the SEIU National Industry Pension Fund (hereinafter referred to as the "NIPF") in order to provide retirement benefits for eligible Employees in accordance with the terms of the NIPF. SCHEDULE B Pages 1-3 (401K Pension Savings Plan) The Buildings (Employers) identified in Schedule B of this Agreement shall contribute for all regular employees to the SEIU Local 1 401(k) Savings Plan in order to provide retirement benefits for eligible Employees in accordance with the terms of the 401(k) Plan. SCHEDULE C Page 1 (DSMOA NIPF) The Buildings and sub-contractors (Employers) identified in Schedule C of this Agreement shall contribute for all regular Employees to the SEIU National Industry Pension Fund (hereinafter referred to as the "NIPF") in order to provide retirement benefits for eligible Employees in accordance with the terms of the NIPF. -

Truevine Missionary Baptist Church Building 6720 South Stewart Avenue

LANDMARK DESIGNATION REPORT Truevine Missionary Baptist Church Building 6720 South Stewart Avenue Preliminary Landmark recommendation approved by the Commission on Chicago Landmarks, July 12, 2006 CITY OF CHICAGO Richard M. Daley, Mayor Department of Planning and Development Lori T. Healey, Commissioner 1 The Commission on Chicago Landmarks, whose nine members are appointed by the Mayor and City Council, was established in 1968 by city ordinance. The Commission is responsible for recommend- ing to the City Council which individual buildings, sites, objects, or districts should be designated as Chicago Landmarks, which protects them by law. The landmark designation process begins with a staff study and a preliminary summary of information related to the potential designation criteria. The next step is a preliminary vote by the landmarks commission as to whether the proposed landmark is worthy of consideration. This vote not only initiates the formal designation process, but it places the review of city permits for the property under the jurisdiction of the Commission until a final landmark recommendation is acted on by the City Council. This Landmark Designation Report is subject to possible revision and amendment during the designation process. Only language contained within the designation ordinance adopted by the City Council should be regarded as final. Cover: The east facade of the Truevine Missionary Baptist Church Building, 6720 S. Stewart Ave., built in 1892 in the Gothic Revival architectural style. Bottom left: Interior of the building’s sanctuary, showing its exposed-truss ceiling and historic lighting. Bottom right: Interior foyer, showing its pointed-arch diamond-paned window and oak wainscoting and staircase leading to the sanctuary’s gallery. -

High-Hise Building Oata Base

High-Hise Building Oata Base Since the inception of the Council, various surveys have been made con cerning the location, number of stories, height, material, and use of tall buildings around the world. The first report on these surveys was published in the Council's Proceedings of the First International Conference in 1972. TaU Building Systems and Concepts (Volume SC) brought that information up to date with a detailed survey in 1980. Changes to some of the data were reflected in Developments in TaU Buildings-1983, with further updating in Advances in TaU Buildings (January, 1986), High-Rise Buildings: Recent Progress (November, 1986), and TaU Build ings 0/ the World (February, 1987). This present volume provides the newer information more recently received. The original survey was based mainly on information collected from individuals in the major cities of the world. The main criterion for the selection of a city was generally its population. Another criterion was the availability of a Council member or other contact who might provide the needed information. This Appendix updates Table l. Because the data came from so many sourees, complete accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Buildings change names or new ones break ground, and this information is sometimes slow in reaching the Council headquarters. In this sense the survey keeps its nature as a "living document." Additions and corrections to the information presented here are welcomed, and should be brought to the attention of Council Headquarters at Lehigh University. 1003 1004 Second Century of the Skyscraper Table 1: World's TaUest Buildings. This is a list of the world's 100 tallest buildings. -

Hybrid Residential Tower Planned in Streeterville

Hybrid residential tower planned in Streeterville A 67-story, 500-unit, yet-unnamed hybrid residential tower is proposed for the Streeterville neighborhood. (Robert A.M. Stern Architects LLP, HANDOUT) By Mary Ellen Podmolik and Blair Kamin, Tribune reporters JULY 18, 2014 67-story, 500-unit hybrid residential tower designed by notable architect Robert A.M. Stern is proposed for the A southwest corner of Grand Avenue and Peshtigo Court by Related Midwest, which has been on a development hot streak for the past few years in Chicago. The tower, with 400 apartments and 100 condominiums, would seek to capitalize on two trends — strong demand for luxury apartments with bountiful amenities and a lack of new condominium units in downtown Chicago. At one time, the Streeterville neighborhood site had been slated for a 28-story, 232-unit condo tower that was to be built by developer Dan McLean, but he lost the site in a foreclosure suit. An affiliate of Related Midwest bought the land in August for $24.6 million, according to county property records. Stern designed Chicago's ubiquitous bus shelters. Sandwiched between the tower and an existing high-rise to the west would be a new public park designed by New York landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh, whose credits include Maggie Daley Park, which is under construction east of Millennium Park. "What they're proposing here certainly fits within the context of the neighborhood and certainly offers the possibility of a very exciting open space that will support the many young families that are in this neighborhood," said Ald.