Red China Through the Lens of Western Leftist Filmmakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Magazine

in this edition : THE 3 Joris Ivens on DVD The release in Europe 6 Joris Ivens 110 Tom Gunning MAGAZINE 9 Politics of Documen- tary Nr 14-15 | July 2009 European Foundation Joris Ivens Michael Chanan ar ers y Jo iv r 16 - Ivens, Goldberg & n is n I a v the Kinamo e h n t Michael Buckland s 0 1 1 s110 e p u ecial iss 40 - Ma vie balagan Marceline Loridan-Ivens 22 - Ivens & the Limbourg Brothers Nijmegen artists 34 - Ivens & Antonioni Jie Li 30 - Ivens & Capa Rixt Bosma July 2009 | 14-15 1 The films of MAGAZINE Joris Ivens COLOPHON Table of contents European Foundation Joris Ivens after a thorough digital restoration Europese Stichting Joris Ivens Fondation Européenne Joris Ivens Europäische Stiftung Joris Ivens 3 The release of the Ivens DVD-box set The European DVD-box set release André Stufkens Office 6 Joris Ivens 110 Visiting adress Tom Gunning Arsenaalpoort 12, 6511 PN Nijmegen Mail 9 Politics of Documentary Pb 606 NL – 6500 AP Nijmegen Michael Chanan Telephone +31 (0)24 38 88 77 4 11 Art on Ivens Fax Anthony Freestone +31 (0)24 38 88 77 6 E-mail 12 Joris Ivens 110 in Beijing [email protected] Sun Hongyung / Sun Jinyi Homepage www.ivens.nl 14 The Foundation update Consultation archives: Het Archief, Centrum voor Stads-en Streekhistorie Nijmegen / Municipal 16 Joris Ivens, Emanuel Goldberg & the Archives Nijmegen Mariënburg 27, by appointment Kinamo Movie Machine Board Michael Buckland Marceline Loridan-Ivens, president Claude Brunel, vice-president 21 Revisit Films: José Manuel Costa, member Tineke de Vaal, member - Chile: Ivens research -

Documentary Films Available in Youtube and Other Online Sources Fall 2018

Documentary films available in YouTube and other online sources Fall 2018 À PROPOS DE NICE (1930), dir. Jean Vigo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xQTf2f7G_Ak BALLET MÉCANIQUE (1924), dir. Fernand Léger https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oWa2iy-0TEQ THE BATTLE OF SAN PIETRO (1945), dir. John Houston https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3OLJZvgIx5w BERLIN, SYMPHONY OF A GREAT CITY (1927), dir. Walther Ruttmann https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lPzyhzyuLYU BLIND SPOT. HITLER’S SECRETARY (2002), dir. Othmar Schmiderer, André Heller https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0NQgIvG-kBM CITY OF GOLD (1957), narrated by Pierre Berton https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KGxHHAX1nOY DRIFTERS (1929), dir. John Grierson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RUOiTNnNFvI HARVEST OF SHAME (1960), dir. Fred Friendly https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yJTVF_dya7E LET THERE BE LIGHT (1946), dir. John Huston https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lQPoYVKeQEs THE LUMIÈRE BROTHERS’ FIRST FILMS (1996) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VHpInwDakwE MANHATTA (1921), dir. Charles Sheeler & Paul Strand https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kuuZS2phD10 MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (1929), dir. Dziga Vertov https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7ZkvjWIEcoU&t=73s MULTIPLY BY SIX MILLION (2007), dir. Evvy Eisen http://www.jewishfilm.org/Catalogue/films/sixmillion.html NANOOK OF THE NORTH (1922), dir. Robert Flaherty https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m4kOIzMqso0 1 THE NEGRO SOLDIER (1944), prod. Frank Capra https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H6YvZy_IsZY NIGHT AND FOG (1956), dir. Alain Resnais https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CPLX8U2SHJE&t=477s NIGHT MAIL (1936), dir. Basil Wright & Harry Watt https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHOHbTL3mpk NUREMBERG: ITS LESSON FOR TODAY (1948), dir. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

French New Wave Showcase

Drafthouse in Richardson are teaming up in September to present a FRENCH NEW WAVE SHOWCASE. A different classic French film will be screened every Saturday afternoon at 4 pm at Alamo. In-person Interviews with Bart Weiss and Dr Frank Dufour (French New Wave expert): Thursday, September 3: Media roundtable from 7:15- 8 pm (This will be the 2nd of 2 Roundtables on Sept 3 - info on the first one follows shortly.) Interviews will take place at La Madeleine near SMU 3072 Mockingbird Ln Dallas, TX 75205-2323 - 214- 696-0800 (We will have the room, which sits behind the order line.) Snacks and drinks will be available, of course. French New Wave Showcase Video Association of Dallas and Alamo Drafthouse Cinema - DFW co-present the French New Wave Showcase Saturday afternoons in September French New Wave, or in French “Nouvelle Vague,” is the style of highly individualistic French film directors of the late 1950s—early ‘60s. Films by New Wave directors were often characterized by fresh techniques using the city streets as character in the films. The New Wave films stimulate discussion about their place in the history of cinema and film. So whether a cinephile or a casual filmgoer, learn more about this distinctly French film movement. French New Wave Showcase, http://videofest.org/french-new-wave- showcase/, presented by the Video Association of Dallas and the Alamo Drafthouse Cinema - DFW, screens every Saturday at 4 pm at Alamo, 100 S Central Expressway, Richardson http://drafthouse.com/calendar/dfw. “The French New Wave was a reaction to the bigness of Hollywood. -

Cinema in Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’

Cinema In Dispute: Audiovisual Adventures of the Political Names ‘Worker’, ‘Factory’, ‘People’ Manuel Ramos Martínez Ph.D. Visual Cultures Goldsmiths College, University of London September 2013 1 I declare that all of the work presented in this thesis is my own. Manuel Ramos Martínez 2 Abstract Political names define the symbolic organisation of what is common and are therefore a potential site of contestation. It is with this field of possibility, and the role the moving image can play within it, that this dissertation is concerned. This thesis verifies that there is a transformative relation between the political name and the cinema. The cinema is an art with the capacity to intervene in the way we see and hear a name. On the other hand, a name operates politically from the moment it agitates a practice, in this case a certain cinema, into organising a better world. This research focuses on the audiovisual dynamism of the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’ and ‘people’ in contemporary cinemas. It is not the purpose of the argument to nostalgically maintain these old revolutionary names, rather to explore their efficacy as names-in-dispute, as names with which a present becomes something disputable. This thesis explores this dispute in the company of theorists and audiovisual artists committed to both emancipatory politics and experimentation. The philosophies of Jacques Rancière and Alain Badiou are of significance for this thesis since they break away from the semiotic model and its symptomatic readings in order to understand the name as a political gesture. Inspired by their affirmative politics, the analysis investigates cinematic practices troubled and stimulated by the names ‘worker’, ‘factory’, ‘people’: the work of Peter Watkins, Wang Bing, Harun Farocki, Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub. -

Chris Marker (II)

Chris Marker (II) Special issue of the international journal / numéro spécial de la revue internationale Image [&] Narrative, vol. 11, no 1, 2010 http://ojs.arts.kuleuven.be/index.php/imagenarrative/issue/view/4 Guest edited by / sous la direction de Peter Kravanja Introduction Peter Kravanja The Imaginary in the Documentary Image: Chris Marker's Level Five Christa Blümlinger Montage, Militancy, Metaphysics: Chris Marker and André Bazin Sarah Cooper Statues Also Die - But Their Death is not the Final Word Matthias De Groof Autour de 1968, en France et ailleurs : Le Fond de l'air était rouge Sylvain Dreyer “If they don’t see happiness in the picture at least they’ll see the black”: Chris Marker’s Sans Soleil and the Lyotardian Sublime Sarah French Crossing Chris: Some Markerian Affinities Adrian Martin Petit Cinéma of the World or the Mysteries of Chris Marker Susana S. Martins Introduction Author: Peter Kravanja Article Pour ce deuxième numéro consacré à l'œuvre signé Chris Marker j'ai le plaisir de présenter aux lecteurs les contributions (par ordre alphabétique) de Christa Blümlinger, de Sarah Cooper, de Matthias De Groof, de Sylvain Dreyer, de Sarah French, d'Adrian Martin et de Susana S. Martins. Christa Blümlinger voudrait saisir le statut théorique des mots et des images « trouvées » que Level Five intègre dans une recherche « semi-documentaire », à l'intérieur d'un dispositif lié aux nouveaux médias. Vous pourrez ensuite découvrir la contribution de Sarah Cooper qui étudie le lien entre les œuvres d'André Bazin et de Chris Marker à partir de la fin des années 1940 jusqu'à la fin des années 1950 et au-delà. -

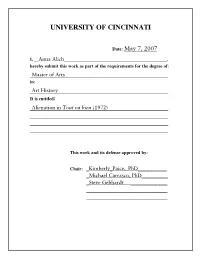

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: May 7, 2007 I, __Anna Alich_____________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: Alienation in Tout va bien (1972) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Kimberly_Paice, PhD___________ _Michael Carrasco, PhD__________ _Steve Gebhardt ______________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Alienation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Tout Va Bien (1972) A thesis presented to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati in candidacy for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History Anna Alich May 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract Jean-Luc Godard’s (b. 1930) Tout va bien (1972) cannot be considered a successful political film because of its alienated methods of film production. In chapter one I examine the first part of Godard’s film career (1952-1967) the Nouvelle Vague years. Influenced by the events of May 1968, Godard at the end of this period renounced his films as bourgeois only to announce a new method of making films that would reflect the au courant French Maoist politics. In chapter two I discuss Godard and the Dziga Vertov Group’s last film Tout va bien. This film displays a marked difference in style from Godard’s earlier films, yet does not display a clear understanding of how to make a political film of this measure without alienating the audience. In contrast to this film, I contrast Guy Debord’s (1931-1994) contemporaneous film The Society of the Spectacle (1973). As a filmmaker Debord successfully dealt with alienation in film. -

COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television

COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media Notes from and about Barnouw’s Documentary: A history of the non-fiction film 6. Documentarist as. Bugler Definition(s): The “bugle-call film”—adjunct to military action, weapon of war—a “call to action” (note that both Listen to Britain and the Why We Fight series literally begin with bugle calls over the opening credits); the filmmaker’s task—to stir the blood Key Concepts & Issues: Use of battle footage—e.g., expanded newsreels in the German Weekly Review Repurposing of captured footage—in WWII, both sides engaged in this (e.g., Why We Fight) “Documenting” a thesis with fiction excerpts (e.g., footage from Drums Along the Mohawk, The Good Earth, Marco Polo, and many others in the Why We Fight series; use of footage from Fritz Lang’s M, clips from Hollywood films and of supposed Jewish performers in Fritz Hippler’s anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda film The Eternal Jew (1940)) Key Documentarists: Humphrey Jennings (1907-1950) A new member of “Grierson’s Boys” (including Alberto Cavalcanti, Paul Rotha) at the GPO Film Unit, which became the Crown Film Unit. A Cambridge graduate with broad arts background, his style was “precise, calm, rich in resonance.” Among his films, one earned him a world-wide reputation: Listen to Britain: (a) Featured Jennings’ specialty, vignettes of human behavior under extraordinary stress—they are heeding the government’s 1939 call to “Keep Calm and Carry On“; (b) Typical of Jennings’ war films— the film never explains, exhorts, or harangues—it observes; -

Downloaded for Personal, Non-Commercial, Research Or Study Without Prior Permission and Without Charge

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Osborne, Richard ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4111-8980 (2011) Colonial film: moving images of the British Empire. Other. [Author]. [Monograph] This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/9930/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

JORIS IVENS' "THE SPANISH EARTH" Author(S): Thomas Waugh Source: Cinéaste , 1983, Vol

"Men Cannot Act in Front of the Camera in the Presence of Death": JORIS IVENS' "THE SPANISH EARTH" Author(s): Thomas Waugh Source: Cinéaste , 1983, Vol. 12, No. 3 (1983), pp. 21-29 Published by: Cineaste Publishers, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/41686180 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Cineaste Publishers, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cinéaste This content downloaded from 95.183.180.42 on Sun, 19 Jul 2020 08:17:33 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms "Men Cannot Act in Front of the Camera in the Presence of Death" JORIS IVENS' THE SPANISH EARTH by Thomas Waugh The first installment of this article burning , churches and the like - as which Jocussed on the political and well as expensive and difficult to piy artistic background to the production out of the notoriously reactionary oj Joris Ivens' Spanish Earth, newsreel companies. The group then appeared in our Vol. XII , No. 2 issue.decided to finish the project as quickly and cheaply as possible, which Van Dongen did using a Dos Passos com- mentary and relying on Soviet footage that the Franco rebellion posed of the front. -

Reparto Extraordinario Salas De Cine 2012-2018

1 de 209 Listado de obras audiovisuales Reparto Extraordinario Com. Púb. Salas de Cine 2012 - 2018 Dossier informativo Departamento de Reparto El listado incluye las obras y prestaciones cuyos titulares no hayan sido identificados o localizados al efectuar el reparto, por lo que AISGE recomienda su consulta para proceder a la identificación de tales titulares. 2 de 209 Tipo Código Titulo Tipo Año Protegida Lengua Obra Obra Obra Producción Producción Globalmente Explotación Actoral 725826 ¡¡¡CAVERRRRNÍCOLA!!! Cine 2004 Castellano Actoral 1051717 ¡A GANAR! Cine 2018 Castellano Actoral 3609 ¡ATAME! Cine 1989 Castellano Actoral 991437 ¡AVE, CESAR! Cine 2016 Castellano Actoral 19738 ¡AY, CARMELA! Cine 1989 Castellano Actoral 6133 ¡FELIZ NAVIDAD, MISTER LAWRENCE! Cine 1982 Castellano Actoral 964045 ¡QUE EXTRAÑO LLAMARSE FEDERICO! Cine 2013 Castellano Actoral 1051718 ¡QUÉ GUAPA SOY! Cine 2018 Castellano Actoral 883562 ¿PARA QUE SIRVE UN OSO? Cine 2011 Castellano Actoral 945650 ¿QUE HACEMOS CON MAISIE? Cine 2012 Castellano Actoral 175 ¿QUE HE HECHO YO PARA MERECER ESTO? Cine 1984 Castellano Actoral 954473 ¿QUE NOS QUEDA? Cine 2012 Castellano Actoral 12681 ¿QUE OCURRIO ENTRE MI PADRE Y TU MADRE? Cine 1972 Castellano Actoral 1051727 ¿QUIÉN ESTÁ MATANDO A LOS MOÑECOS? Cine 2018 Castellano Actoral 925329 ¿QUIEN MATO A bAMbI? Cine 2013 Castellano Actoral 801520 ¿QUIEN QUIERE SER MILLONARIO? Cine 2008 Castellano Actoral 12772 ¿QUIEN TEME A VIRGINIA WOOLF? Cine 1966 Castellano Actoral 1020330 ¿TENIA QUE SER EL? Cine 2017 Castellano Actoral 884410 ¿Y -

National Gallery of Art Fall10 Film Washington, DC Landover, MD 20785

4th Street and Mailing address: Pennsylvania Avenue NW 2000B South Club Drive NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART FALL10 FILM Washington, DC Landover, MD 20785 FIGURES IN A STRAUB AND LANDSCAPE: JULIEN HUILLET: THE NATURE AND DUVIVIER: WORK AND HARUN NARRATIVE THE GRAND REACHES OF FAROCKI: IN NORWAY ARTISAN CREATION ESSAYS When Angels Fall Manhattan cover calendar page calendar (Harun Farocki), page four page three page two page one Still of performance duo ZsaZa (Karolina Karwan) When Angels Fall (Henryk Kucharski) A Tale of HarvestA Tale The Last Command (Photofest), Force of Evil Details from FALL10 Images of the World and the Inscription of War (Henryk Kucharski), (Photofest) La Bandera (Norwegian Institute) Film Images of the (Photofest) (Photofest) Force of Evil World and the Inscription of War (Photofest), Tales of (Harun Farocki), Iris Barry and American Modernism Andrew Simpson on piano Sunday November 7 at 4:00 Art Films and Events Barry, founder of the film department at the Museum of Modern Art , was instrumental in first focusing the attention of American audiences on film as an art form. Born in Britain, she was also one of the first female film critics David Hockney: A Bigger Picture and a founder of the London Film Society. This program, part of the Gallery’s Washington premiere American Modernism symposium, re-creates one of the events that Barry Director Bruno Wollheim in person staged at the Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford in the 1930s. The program Saturday October 2 at 2:00 includes avant-garde shorts by Walter Ruttmann, Ivor Montagu, Viking Eggeling, Hans Richter, Charles Sheeler, and a Silly Symphony by Walt Disney.