Escholarship California Italian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mantegna's Lamentation Over the Dead Christ

DESCRIVEDENDO THE MASTERPAINTINGS OF BRERA The Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Andrea Mantegna Pinacoteca di Brera, Room 6 Formal Description Christ Dead in the Tomb with Three Mourners is the official title of this picture painted by Andrea ManteGna, probably around 1483. It is a work in tempera on canvas painted in a realistic manner and is quite complex to describe. The painting is rectangular in shape, its horizontal side slightly longer than its vertical side. It is 81 centimetres wide and 68 centimetres high. The scene depicted takes place in the tomb, where Jesus Christ's lifeless body has been laid on a slab of marble to be cleaned and oiled with perfumed ointment before burial. Besides Jesus, on one side of the canvas, we see the Grieving faces of a man and two women. The physical presence of Jesus's body dominates the painting, filling most of the available space. Jesus is shown as thouGh we were observinG him from a sliGhtly hiGher viewpoint, not by his side but facinG him from the feet up. His body is thus painted entirely alonG the canvas's vertical axis and so we see the soles of his feet in the foreGround close to the lower edGe, while if we lift our Gaze we move up his body as far as his head in the distance, close to the upper edGe. It is as thouGh Jesus's whole body were compressed between the upper and lower edGes of the canvas: the painter depicts his anatomy realistically, but in a distorted manner in which he has sliGhtly changed the dimensions of the body's individual parts so as to make the perspective he adopts believable. -

Alexander Nagel Some Discoveries of 1492

The Seventeenth Gerson Lecture held in memory of Horst Gerson (1907-1978) in the aula of the University of Groningen on the 14th of November 2013 Alexander Nagel Some discoveries of 1492: Eastern antiquities and Renaissance Europe Groningen The Gerson Lectures Foundation 2013 Some discoveries of 1492: Eastern antiquities and Renaissance Europe Before you is a painting by Andrea Mantegna in an unusual medium, distemper on linen, a technique he used for a few of his smaller devotional paintings (fig. 1). Mantegna mixed ground minerals with animal glue, the kind used to size or seal a canvas, and applied the colors to a piece of fine linen prepared with only a very light coat of gesso. Distemper remains water soluble after drying, which allows the painter greater flexibility in blending new paint into existing paint than is afforded by the egg tempera technique. In lesser hands, such opportunities can produce muddy results, but Mantegna used it to produce passages of extraordinarily fine modeling, for example in the flesh of the Virgin’s face and in the turbans of wound cloth worn by her and two of the Magi. Another advantage of the technique is that it produces luminous colors with a matte finish, making forms legible and brilliant, without glare, even in low light. This work’s surface was left exposed, dirtying it, and in an effort to heighten the colors early restorers applied varnish—a bad idea, since unlike oil and egg tempera distem- per absorbs varnish, leaving the paint stained and darkened.1 Try to imagine it in its original brilliant colors, subtly modeled throughout and enamel smooth, inviting us to 1 Andrea Mantegna approach close, like the Magi. -

Children's Discovery Trail.Pub

Children's Discovery Trail Exposition Mantegna 26 septembre 2008 - 5 janvier 2009 Mantegna was very interested in small details. Look very carefully at his paintings. If you do this you will be able to understand them better. His art is based on close observation and poetry. Every time you see this sign, look carefully at the detail reproduced then search for it in the work. 1 Andrea Mantegna, SAINT EUPHEMIA These fruits are part of the garland decorating the arch on which the saint's name is written "Santa Eufemia". Look at the sculpture just on your left and com- pare it with the painting. Are the clothes the same? Are the feet placed in the same way? Is the lion in the same place? What is it doing? He looks as though it is nibbling her hand. Now you can see that the sculptor used the painting as a model. Children's Discovery Trail 2 Andrea Mantegna, THE ADORATION OF THE SHEPHERDS This angel with red wings is telling a shepherd that a child called Jesus has been born. The two men in the foreground – look at them ; one of them is the same as the shepherd on the mountain? Which route did he take to come down and see the new-born child. We can give you a clue – he is holding a hat. Then, count the number of sheep in the background. Children's Discovery Trail 3 Andrea Mantegna, PRAYER IN THE GARDEN This cheeky rabbit is crossing the bridge on the left of the painting. In the middle there are some peculiar round constructions. -

Sensory Reality As Perceived Through the Religious Iconography of the Renaissance

Sensory reality as perceived through the religious iconography of the Renaissance Maria Athanasekou, Athens In Della pittura, Leon Battista Alberti wrote: “No one would deny that the painter has nothing to do with things that are not visible. The painter is concerned solely with representing what can be seen.”1 What Alberti does not mention is that during the Trecento, as well as in his own time, painted surfaces were populated with things that are not visible, with saints and angels, seraphims and cherubims, even the Madonna, Jesus and the Almighty God. The reality of all religious paintings of the Renaissance is virtually inhabited by heavenly and otherworldly creatures, taking the viewer onto a metaphysical level of experience and mystical union with the celestial cosmos. Physical space is intertwined with the supernatural environment that holy fig- ures occupy, and religious paintings systematically form another ac- tuality, a virtual reality for the viewer to experience and sense. In most cases this dynamic new world is the result of the com- bined efforts of the artist and the client (or patron), as specific details regarding the execution, content, materials, cost and time of delivery were stipulated in contracts. Hence, the scenographic virtuality of sa- cred images was produced by real people who wished to construct an alternative sensory reality in which they are portrayed alongside holy men and women. During the period ranging from the later Middle Ages to the end of the seventeenth century, Europeans believed that their heads contained three ventricles. In these, they were told, their faculties were processed, circulated and stored the sensory 1 Alberti 1967, 43. -

Letter of Ludovico Gonzaga to Andrea Mantegna, 15 April 1458

Letter of Ludovico Gonzaga to Andrea Mantegna, 15 April 14581 wait another six months in order to finish the work for the Reverend Ludovico Gonzaga’s desire to be in the lead among princely patrons inspired protonotary of Verona and dispatch the rest of your business, we are very him to lure Mantegna from Padua to be his resident court painter. He had already made overtures in the previous year, though Mantegna was slow to content, and if these six months are not enough for you, take seven or commit himself while still working on the famous altarpiece of San Zeno, Verona, eight, so that you can finish everything you have begun and come here for the Protonotary Gregorio Correr. The terms offered were certainly generous: 180 ducats a year was a considerable salary to accompany the other perquisites. with your mind at rest. Two or three months are not going to make any It is not clear, however, whether on acceptance Mantegna protected himself by a formal contract; the following letter suggests he did not. He finally arrived in the difference to us provided that we have the certainty from you that when summer of 1459; his mind may have been made up by the Congress held in the time comes you will not fail to enter our service, and if you come next Mantua that year (the same event which brought Alberti to the Gonzaga court), with its opportunities of further patronage. January you would still be in good time. We deeply beg that by that time without fail you will want to come, as we hope. -

Lamentation Over the Dead Christ

1 PINACOTECA DI BRERA BIBLIOTECA NAZIONALE BRAIDENSE Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo Via Brera 28, 20121 Milano t +39 02 72263264 - 229 [email protected] www.pinacotecabrera.org press release June, 13th 2016 Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera June, 16th 2016- Grand Opening: free admission from 8.30 a.m. to 10.15 p.m. MANTEGNA AND CARRACCI. AROUND THE LAMENTATION OVER THE DEAD CHRIST Annibale Carracci’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ is coming to Brera 2 to engage in dialogue with Andrea Mantegna’s masterpiece. rom 16 June to 25 September 2016 the Pinacoteca di Brera will be hosting a spectacular new dialogue between two masterpieces in the history of world art: FAndrea Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ, one of the Milan picture gallery’s most emblematic works and a universal icon of the Renaissance, and the Corpse of Christ (or The Body of Christ and the Implements of His Martyrdom), a version of the same subject painted by Annibale Carracci in 1583–1585 and on loan from the Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart. The two works, displayed side by side for the very first time, comprise the second outstanding dialogue devised by the Pinacoteca di Brera, a museum in the process of renewing its approach in an effort to offer its visitors food for thought with a collec- tion that includes some of the most important masterpieces of painting in the world. Mantegna’s work will be shown not only alongside Carracci’s version but also with another version of the same theme, the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, painted by Orazio Borgianni in 1615 and on loan from the Galleria Spada in Rome. -

Mantegna's Mars and Venus

Abstract Title of Document: Mantegna’s Mars and Venus: The Pursuit of Pictorial Eloquence Steven J. Cody, Master of Arts, 2009 Directed By: Professor Meredith J. Gill, Department of Art History and Archeology This paper examines the pictorial composition of Andrea Mantegna’s Mars and Venus and its relation to the culture of letters and antiquarianism present in the studiolo of Isabella d’Este Gonzaga. By analyzing Mantegna’s use of contrapposto, a visual motif stemming from the rhetorical figure of “antithesis,” I argue that the artist formally engages Classical rhetoric and the principles of Leon Battista Alberti’s De Pictura. Mantegna’s dialogue with Albertian and rhetorical theory visually frames the narrative of Mars and Venus in a way that ultimately frames the viewer’s understanding of Isabella’s character as a patron of the arts. But it also has ramifications for how the viewer understands Mantegna’s activities as a painter. By focusing my investigation on the significance of pictorial form and Mantegna’s process of imitation, I look to emphasize the intellectual nuances of Isabella’s approach to image making and to link Mantegna’s textual knowledge to his visual recuperation of Classical art. MANTEGNA’S MARS AND VENUS: THE PURSUIT OF PICTORIAL ELOQUENCE By Steven J. Cody Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2009 Advisory Committee: Professor Meredith J. Gill, Chair Professor Anthony Colantuono Professor Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. © Copyright by Steven Joseph Cody 2009 Disclaimer The thesis document that follows has had referenced material removed in respect for the owner’s copyright. -

Camera Degli Sposi” of Mantegna (Mantova)

International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XL-5/W2, 2013 XXIV International CIPA Symposium, 2 – 6 September 2013, Strasbourg, France SURVEY METHODS FOR EARTHQUAKE DAMAGES IN THE “CAMERA DEGLI SPOSI” OF MANTEGNA (MANTOVA) E. Fratus de Balestrini a, M. Ballarin a, C. Balletti a, V. Buttolo a, C. Gottardi b, F. Guerra a, S. Mander a, L. Pilot a, P. Vernier a a Laboratorio di Fotogrammetria, Sistema dei Laboratori, Università Iuav di Venezia, Santa Croce 191, 30135 Venezia, Italy - (edebalestrini, martinab, balletti, buttolo, guerra2, vernier)@iuav.it b [email protected] KEY WORDS: Earthquake, Laser scanner, Cultural Heritage, Camera degli Sposi, Mantegna ABSTRACT: Cultural Heritage constitutes a fundamental resource for all Countries, even in economic terms, as it can be considered an extraordinary tourist attraction. This is particularly true for Italy, which is one of the Countries with the richest artistic heritage in the world. For this reason, restoration becomes an essential step towards the conservation and therefore valorisation of architecture. In this context, this paper focuses on one of the first stages that allow us to reach a complete knowledge of a building. Because of the earthquake of May 2012, the Castle of San Giorgio in Mantova (Italy) presented a series of structural damages. On the occasion of its upcoming re-opening to the public, the Soprintendenza per i Beni Architettonici e Paesaggistici per le province di Brescia, Cremona e Mantova has requested an analysis and evaluation of the damages for the development of an intervention project. In particular, a special attention was given to the “Camera degli Sposi” ("Bridal Chamber"), also known as the Camera picta ("painted chamber"). -

Gardens and Grottoes in Later Works by Mantegna Carola Naumer

Gardens and Grottoes in Later Works by Mantegna Carola Naumer The Renaissance artist, Andrea Mantegna, consistently Mantua like that of her great-uncle, Leonello d’Este in Ferrara.2 incorporated garden elements into a number of his paintings. Her brother, Alfonso I d’Este, continued the family tradition Several of his major works feature garden architecture, in- of creating a space for contemplation and commissioning works cluding trellises, pergolas, pavilions, and grottoes, as well as on a theme to decorate it. Both Isabella and her brother chose lesser categories like bowers, woven fences, topiaries, and works involving garden themes, reflecting their family’s en- potted plants. An interest in contemporary garden design and thusiastic interest in this pastime.3 plantings enlivens many of his compositions, and his figures Mantegna had gone to Rome in 1489 to paint the chapel demonstrate his knowledge of sculpture displayed in gardens. of the Villa Belvedere, the Vatican residence surrounded by His works include references to antique sculptural works, both the papal gardens. He was called back to Mantua in 1490 when casually assembled fragments as well as well-preserved works the chapel was finished to help organize the wedding of displayed in an organized fashion. As one would expect from Francesco Gonzaga to Isabella d’Este, an alliance which would such a powerful sub-text in an artist’s work, garden motifs are combine the power and artistic patronage of two great houses.4 present in both his religious and mythological paintings. He Isabella’s artistic taste and her family’s interest in gardens used garden elements within his paintings to enhance the il- had a major influence on her new husband, Francesco. -

Solving the Mystery of the Sitter in Bartolomeo Veneto's Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress

Solving the Mystery of the Sitter in Bartolomeo Veneto’s Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress Tatiana Sizonenko Fig. 1. Bartolomeo Veneto, Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress, 1530, The Timken Museum of Art, San Diego. Source: Wiki Art online, public domain, http://www.wikiart.org/en/bartolomeo-veneto/portrait-of-a-lady-in- a-green-dress-1530, consulted June 30, 2016. Introduction Portraits of individuals were ubiquitous in Italy and Northern Europe in the Renaissance. By 1500, portraits were used in a wide range of public and private contexts to celebrate individual likenesses, feature idealized exemplary types, and fashion and project specific social identities of their subjects. Displayed to attract public interest and curiosity, portraits were frequently commissioned as a means to show dynastic pride and often came alive through spoken discourse—a vital component of their public presentation, recognition, and reception.1 Despite 1 Joanna Woods-Marsden, “‘Ritratto al Naturale’: Questions of Realism and Idealism in Early Renaissance Portraits,” Art Journal 46 (1987): 209–216. Patrcia Simons, “Portraiture, Portrayal, and Idealization: Ambiguous 1 the genre’s popularity, the great majority of portraits do not include the name, crest, or other explicit evidence of the sitter’s identity. Although recent scholarship has discouraged attempts to attach biographies to unknown sitters,2 when a portrait can be linked to a specific historical context, it helps advance our understanding of the function of portraiture in the Renaissance and explore the fixity and flexibility of individual likenesses. Bartolomeo Veneto’s Portrait of a Lady in a Green Dress (fig. -

Andrea Mantegna Great Hasters in Painting and Sculpture

QREflT MASTERS IN POINTING & SCULPTURE The Great Masters in Painting and Sculpture Edited by Q. C. Williamson ANDREA MANTEGNA GREAT HASTERS IN PAINTING AND SCULPTURE The following volumes have been issued. 55. net each. BERNARDINO LUINI. By GEORGE C. WILLIAMSON, Litt. D. VELAZQUEZ. By R. A. M. STEVENSON. ANDREA DEL SARTO. By H. GUINNESS. LUCA SIGNORELLI. By MAUD CRUTTWELL, RAPHAEL. By H. STRACHEY. CARLO CRIVELLI. By G. McNEiL RUSHFORTH, M.A. CORREGGIO. By SELWYN BRINTON, M.A. DONATELLO. By HOPE REA. PERUGINO. By G. C. WILLIAMSON, Litt. D. SODOMA. By the CONTESSA LORENZO PRIULI-BON. LUCA DELLA ROBBIA. By the MARCHESA BURLAMACCHI. GIORGIONE. By HERBERT COOK, M.A. MEMLINC. By W H. JAMES WEALE. PIERO DELLA FRANCESCA. By W. G. WATERS, M.A. PINTORICCHIO. By E. MARCH PHILLIPPS. FRANCIA. By GEORGE C. WILLIAMSON, Litt. D. BRUNELLESCHI. By LEADER SCOTT. MANTEGNA. By MAUD CRUTTWELL. REMBRANDT. By MALCOLM BELL. In Preparation. GIOTTO. By F. MASON PERKINS. EL B. Litt. D. Ph. D. GRECO. By MANUEL Cossio, , WILKIE. By LORD RONALD SUTHERLAND-GOWER, M.A., F.S.A., GERARD DOU. By W. MARTIN, Ph. D. DURER. By HANS W. SINGER, M.A., Ph.D. TINTORETTO. By J. B. STOUGHTON HOLBORN, M.A. PAOLO VERONESE. By ROGER E. FRY. GAUDENZIO FERRARI. By ETHEL HALSEY. Others to follow. LONDON : GEORGE BELL & SONS rt- ( (in/i/mf C>//Y//V////'/. ANDREA MANTEGNA BY MAUD CRUTTWELL " Author of LUCA SIGNORELLI," Etc. LONDON GEORGE BELL AND SONS 1901 PREFACE is with much diffidence that I have undertaken a ITwork which deals with a Genius so great as Mantegna, a work which I am fully conscious should be attempted only by one far better equipped than myself to comprehend the grandeur of the movement of which he was representative. -

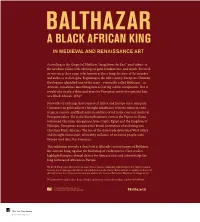

In Medieval and Renaissance Art

BALTHAZAR A BLACK AFRICAN KING IN MEDIEVAL AND RENAISSANCE ART According to the Gospel of Matthew, “magi from the East” paid tribute to the newborn Christ with offerings of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Revered as wise men, they came to be known as three kings because of the number and richness of their gifts. Beginning in the fifth century, European Christian theologians identified one of the magi—eventually called Balthazar—as African, sometimes describing him as having a dark complexion. But it would take nearly a thousand years for European artists to represent him as a Black African. Why? Networks of exchange had connected Africa and Europe since antiquity. Commerce in gold and ivory brought inhabitants of both continents into frequent contact, and Black African soldiers served in the courts of medieval European rulers. Yet in the fifteenth century, even as the Papacy in Rome welcomed Christian delegations from Coptic Egypt and the kingdom of Ethiopia, Europeans escalated the brutal institution of enslaving non- Christian Black Africans. The rise of the slave trade devastated West Africa and brought thousands, ultimately millions, of enslaved peoples into Europe (and later, the Americas). This exhibition provides a close look at fifteenth-century images of Balthazar, the African king, against the backdrop of enslavement. Case studies highlight Europe’s colonial desires for Africa’s riches and acknowledge the long histories of Africans in Europe. Medieval Europe and Africa were far more diverse than is commonly acknowledged, not only in terms of race but also in language and religion. This exhibition uses the phrase “Black African” to underscore the racial diversity across the African continent and to address the theme of Balthazar’s Blackness in European art.