Chapter 21 Renaissance in Quattrocento Italy.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stepping out of Brunelleschi's Shadow

STEPPING OUT OF BRUNELLESCHI’S SHADOW. THE CONSECRATION OF SANTA MARIA DEL FIORE AS INTERNATIONAL STATECRAFT IN MEDICEAN FLORENCE Roger J. Crum In his De pictura of 1435 (translated by the author into Italian as Della pittura in 1436) Leon Battista Alberti praised Brunelleschi’s dome of Florence cathedral, Santa Maria del Fiore [Fig. 1], as ‘such a large struc- ture’ that it rose ‘above the skies, ample to cover with its shadow all the Tuscan people’.1 Alberti was writing metaphorically, but he might as easily have written literally in prediction of the shadowing effect that Brunelleschi’s dome, dedicated on 30 August 1436, would eventually cast over the Florentine cultural and historical landscape of the next several centuries.2 So ever-present has Brunelleschi’s structure been in the historical perspective of scholars – not to mention in the more popular conception of Florence – that its stately coming into being in the Quattrocento has almost fully overshadowed in memory and sense of importance another significant moment in the history of the cathedral and city of Florence that immediately preceded the dome’s dedication in 1436: the consecration of Santa Maria del Fiore itself on 25 March of that same year.3 The cathedral was consecrated by Pope Eugenius IV (r. 1431–1447), and the ceremony witnessed the unification in purpose of high eccle- siastical, foreign, and Florentine dignitaries. The event brought to a close a history that had begun 140 years earlier when the first stones of the church were laid in 1296; in 1436, the actual date of the con- secration was particularly auspicious, for not only is 25 March the feast of the Annunciation, but in the Renaissance that day was also the start of the Florentine calendar year. -

Classicism, Modernism, Postmodernism, and Importance of Communication

Classicism, Modernism, Postmodernism, and Importance of Communication Taylor Stevenson Art History II Prof Jason Bernagozzi Midterm Exam March 09, 2016 Art and societies have long since been integrated, with both realms reflecting each other through understandings, values, and ideas. When either realm changes its ideologies, the other realm tends to reflect those changes in a similar form. This is prevalent in the understanding of art movements over the course of history, especially with three periods of art: Classicism, Modernism, and Post Modernism. Through these art movement periods, we can see how ideologies of the artist have evolved from working for other professions that use art as a means to an end, to using art as a way to communicate their own ideas, to creating art for the viewer to decide on the meaning. Many artworks that were taken from (or inspired by) Greek and Roman cultural art are considered to be classical. This may be because at this point in time, the societies behind these works of art have established an aesthetic standard that serves as a fundamental basis for other art movements. The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica note “’classic’ is also sometimes used to refer to a stage of development that some historians have identified as a regular feature of what they have seen as the cyclical development of all styles.” When applied to art (especially art in the western/European world), these “classic” greek and roman roots placed emphasis on a realistic form, and line over color in two dimensional pieces1. Sculptures of these times, while considered important, did not necessarily translate into the aesthetic view of the next generation. -

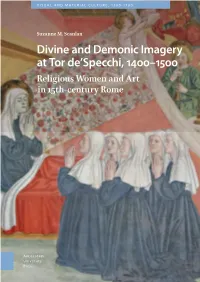

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Suzanne M. Scanlan M. Suzanne Suzanne M. Scanlan Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in 15th-century Rome at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 de’Specchi, Tor at Divine and Demonic Imagery Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes mono- graphs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seeming- ly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Women, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. Divine and Demonic Imagery at Tor de’Specchi, 1400–1500 Religious Women and Art in Fifteenth-Century Rome Suzanne M. Scanlan Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Attributed to Antoniazzo Romano, The Death of Santa Francesca Romana, detail, fresco, 1468, former oratory, Tor de’Specchi, Rome. Photo by Author with permission from Suor Maria Camilla Rea, Madre Presidente. -

Painting Perspective & Emotion Harmonizing Classical Humanism W

Quattrocento: Painting Perspective & emotion Harmonizing classical humanism w/ Christian Church Linear perspective – single point perspective Develops in Florence ~1420s Study of perspective Brunelleschi & Alberti Rules of Perspective (published 1435) Rule 1: There is no distortion of straight lines Rule 2: There is no distortion of objects parallel to the picture plane Rule 3: Orthogonal lines converge in a single vanishing point depending on the position of the viewer’s eye Rule 4: Size diminishes relative to distance. Size reflected importance in medieval times In Renaissance all figures must obey the rules Perspective = rationalization of vision Beauty in mathematics Chiaroscuro – use of strong external light source to create volume Transition over 15 th century Start: Expensive materials (oooh & aaah factor) Gold & Ultramarine Lapis Lazuli powder End: Skill & Reputation Names matter Skill at perspective Madonna and Child (1426), Masaccio Artist intentionally created problems to solve – demonstrating skill ☺ Agonistic Masaccio Dramatic shift in painting in form & content Emotion, external lighting (chiaroscuro) Mathematically constructed space Holy Trinity (ca. 1428) Santa Maria Novella, Florence Patron: Lorenzo Lenzi Single point perspective – vanishing point Figures within and outside the structure Status shown by arrangement Trinity literally and symbolically Vertical arrangement for equality Tribute Money (ca. 1427) Brancacci Chapel in Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence Vanishing point at Christ’s head Three points in story Unusual -

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(S): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus Et Historiae , 2001, Vol

Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning Author(s): Joseph Manca Source: Artibus et Historiae , 2001, Vol. 22, No. 44 (2001), pp. 51-76 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1483713?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae This content downloaded from 130.56.64.101 on Mon, 15 Feb 2021 10:47:03 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms JOSEPH MANCA Moral Stance in Italian Renaissance Art: Image, Text, and Meaning "Thus the actions, manners, and poses of everything ness. In Renaissance art, gravity affects all figures to some match [the figures'] natures, ages, and types. Much extent,differ- but certain artists took pains to indicate that the solidity ence and watchfulness is called for when you have and a fig- gravitas of stance echoed the firm character or grave per- ure of a saint to do, or one of another habit, either sonhood as to of the figure represented, and lack of gravitas revealed costume or as to essence. -

Excavating the Page: Virtuosity and Illusionism in Italian Book Illumination, 1460–1520 Nicholas Herman Available Online: 02 Aug 2011

This article was downloaded by: [Metropolitan Museum of Art] On: 08 August 2011, At: 08:06 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Word & Image Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/twim20 Excavating the page: virtuosity and illusionism in Italian book illumination, 1460–1520 Nicholas Herman Available online: 02 Aug 2011 To cite this article: Nicholas Herman (2011): Excavating the page: virtuosity and illusionism in Italian book illumination, 1460–1520, Word & Image, 27:2, 190-211 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02666286.2010.526289 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Excavating the page: virtuosity and illusionism in Italian book illumination, – NICHOLAS HERMAN So we must advance from the concrete whole to the several These pictorial layers, their distance relative to the viewer, constituents which it embraces; for it is the concrete whole and their progression from literal presence (the clusters of jew- that is the more readily recognizable by the senses. -

The Best of Renaissance Florence April 28 – May 6, 2019

Alumni Travel Study From Galleries to Gardens The Best of Renaissance Florence April 28 – May 6, 2019 Featuring Study Leader Molly Bourne ’87, Professor of Art History and Coordinator of the Master’s Program in Renaissance Art at Syracuse University Florence Immerse yourself in the tranquil, elegant beauty of Italy’s grandest gardens and noble estates. Discover the beauty, drama, and creativity of the Italian Renaissance by spending a week in Florence—the “Cradle of the Renaissance”—with fellow Williams College alumni. In addition to a dazzling array of special openings, invitations into private homes, and splendid feasts of Tuscan cuisine, this tour offers the academic leadership of Molly Bourne (Williams Class of ’87), art history professor at Syracuse University Florence. From the early innovations of Giotto, Brunelleschi, and Masaccio to the grand accomplishments of Michelangelo, our itinerary will uncover the very best of Florence’s Renaissance treasury. Outside of Florence, excursions to delightful Siena and along the Piero della Francesca trail will provide perspectives on the rise of the Renaissance in Tuscany. But the program is not merely an art seminar—interactions with local food and wine experts, lunches inside beautiful private homes, meanders through stunning private gardens, and meetings with traditional artisans will complement this unforgettable journey. Study Leader MOLLY BOURNE (BA Williams ’87; PhD Harvard ’98) has taught art history at Syracuse University Florence since 1999, where she is also Coordinator of their Master’s Program in Renaissance Art History. A member of the Accademia Nazionale Virgiliana, she has also served as project researcher for the Medici Archive Project and held a fellowship at Villa I Tatti, the Harvard Center for Renaissance Studies. -

Sandro Botticelli

4(r A SANDRO BOTTICELLI BY E. SCHAEFFER TRANSLATED BY FRANCIS F. COX New York : FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY Printed in Great Britain. All rights reserved. — — — CONTENTS troductory— Botticelli's Place in Florentine Art—His Early History—Filippo Lippi, the Pollajuoli, Verrocchio Fortitude—Judith and Holofernes—S. Sebastian—Botticelli, Landscape Artist—Painter of Madonnas— Influence of Dante—The Magnificat —Madonna of the Palms— Adoration of the Magi— The Medici at Florence S. Augustine— Botticelli Summoned to Rome—The Frescoes of the Sistine Chapel—The Louvre Frescoes—Leone Battista Alberti Pallas Subduing a Centaur— Spring — TSirth of Venus—Mars and Venus— Calumny of Apelles—Savonarola—The Nativity—The Divina Commedia—Poverty and Neglect—The End—List of Works. ILLUSTRATIONS Mars and Venus. London, National Gallery (Photo- gravure) Frontispiece Facing page Fortitude. Florence, Uffizi 6 S. Sebastian. Berlin, Royal Gallery . .10 Head of the Madonna. Florence, Uffizi (From the " Mag- nificat ") . 20 The Daughters of Jethro. Rome, Sistine Chapel (Detail from the History of Moses) 36 Spring. Florence, Accademia 4.4. The Birth of Venus. Florence, (Photogravure) Uffizi . 46 Salome. Florence, Accademia ...... 50 The Calumny of Apelles. Florence, Uffizi . .52 The Nativity, London, National Gallerv .... 60 SANDRO BOTTICELLI I a chapel of the church of S. Maria Maggiore INat Florence there was preserved during long centuries a painting of the Assumption of the Virgin, the creation of Sandro Botticelli. The Holy Inquisition had detected in this apparently- pious work the taint of an abominable heresy, and shrouded it by means of a curtain from the gaze of true believers. For Botticelli in his conception of the angels had adhered to a damnable doctrine of Origen, who maintained that the souls of those angels who remained neutral at the time of Lucifer's rebellion were doomed by the Deity to work out their salvation by undergoing a period of probation in the bodies of men. -

Mantegna's Lamentation Over the Dead Christ

DESCRIVEDENDO THE MASTERPAINTINGS OF BRERA The Lamentation over the Dead Christ by Andrea Mantegna Pinacoteca di Brera, Room 6 Formal Description Christ Dead in the Tomb with Three Mourners is the official title of this picture painted by Andrea ManteGna, probably around 1483. It is a work in tempera on canvas painted in a realistic manner and is quite complex to describe. The painting is rectangular in shape, its horizontal side slightly longer than its vertical side. It is 81 centimetres wide and 68 centimetres high. The scene depicted takes place in the tomb, where Jesus Christ's lifeless body has been laid on a slab of marble to be cleaned and oiled with perfumed ointment before burial. Besides Jesus, on one side of the canvas, we see the Grieving faces of a man and two women. The physical presence of Jesus's body dominates the painting, filling most of the available space. Jesus is shown as thouGh we were observinG him from a sliGhtly hiGher viewpoint, not by his side but facinG him from the feet up. His body is thus painted entirely alonG the canvas's vertical axis and so we see the soles of his feet in the foreGround close to the lower edGe, while if we lift our Gaze we move up his body as far as his head in the distance, close to the upper edGe. It is as thouGh Jesus's whole body were compressed between the upper and lower edGes of the canvas: the painter depicts his anatomy realistically, but in a distorted manner in which he has sliGhtly changed the dimensions of the body's individual parts so as to make the perspective he adopts believable. -

Masaccio's Holy Trinity

Masaccio's Holy Trinity Masaccio, Holy Trinity, c. 1427, Fresco, 667 x 317 cm, Santa Maria Novella, Florence Masaccio was the first painter in the Renaissance to incorporate Brunelleschi's discovery in his art. He did this in his fresco called The Holy Trinity, in Santa Maria Novella, in Florence. Have a close look at the painting and at this perspective diagram. Can you see the orthogonals (look for diagonal lines that appear to recede into the distance)? Because Masaccio painted from a low viewpoint -- as though we were looking up at Christ, we see the orthogonals in the ceiling, and if we traced all of the orthogonals the vanishing point would be below the base of the cross. My favorite part of this fresco is God's feet. Actually, you can only really see one of them. Why, you may ask, do I have a thing for God's feet (or foot)? Well, think about it for a minute. God is standing in this painting. Doesn't that strike you as odd just a little bit? This may not strike you all that much when you first think about it because our idea of God, our picture of him in our minds eye -- as an old man with a beard, is very much based on Renaissance images of God. So, here Masaccio imagines God as a man. Not a force or a power, or something abstract like that, but as a man. A man who stands -- his feet are foreshortened, and he weighs something and walks, and, I suppose, even has toenails! In medieval art, God was often represented by a hand, just a hand, as though God was an abstract force or power in our lives, but here he seems so much like a flesh and blood man! This is a good indication of Humanism in the Renaissance. -

Medieval Or Early Modern

Medieval or Early Modern Medieval or Early Modern The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton Medieval or Early Modern: The Value of a Traditional Historical Division Edited by Ronald Hutton This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Ronald Hutton and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7451-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7451-9 CONTENTS Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Ronald Hutton Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 10 From Medieval to Early Modern: The British Isles in Transition? Steven G. Ellis Chapter Three ............................................................................................ 29 The British Isles in Transition: A View from the Other Side Ronald Hutton Chapter Four .............................................................................................. 42 1492 Revisited Evan T. Jones Chapter Five ............................................................................................. -

6. After Modernity: Rohmer's Classicism and Universalism

6. After Modernity: Rohmer’s Classicism and Universalism Grosoli, Marco, Eric Rohmer’s Film Theory (1948-1953). From ‘école Schérer’ to ‘Politique des auteurs’. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018 doi: 10.5117/978946298580/ch06 Abstract From the outset of his career, Eric Rohmer made no secret of his preference for classicism, as far as both aesthetics in general and cinematic aesthetics in particular are concerned. One must hasten to add, however, that he never really conceived of “classic” and “modern” as two opposite concepts. Rather, he maintained that what is truly classic is also truly modern, because in either case genuine art is primarily about achieving a certain harmony with nature. What he exactly meant by this forms the main subject matter of this chapter, which also clarifies the degree to which Rohmer’s aesthetics can be called “universalist” and “anti-evolutionist”, and why. In addition, Rohmer’s views on the key notions of authorship and mise en scene are also summarily sketched. Keywords: Rohmer, classic, modern, universalism, aesthetics 6.1. Beyond modern art Rohmer’s attachment to classical tragedy is a clear token of his overt classi- cism, which can hardly be accounted for as orthodox and one-dimensional. For him, ‘classicism’ and ‘modernity’ are not necessarily opposite. In order to clarify this issue, it is again useful to draw upon Kant, since the critic’s classicism and his peculiar, idiosyncratic Kantism ultimately shed a decisive light on each other. For one thing, Rohmer does not connect cinema and Kantian aesthetics in a straightforward way. Contrary to what the previous chapter(s) might have suggested, in spite of cinema’s capability to attain artistic and natural beauty and to tackle freedom, it would be too simplistic to maintain that Rohmer regarded cinema simply as the perfect match to Kant’s ideas on aesthetics.