A Key Vector of Grapevine Leafroll Disease in Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abiotic and Biotic Pest Refuges Hamper Biological Control of Mealybugs in California Vineyards K.M

____________________________________ Abiotic and biotic pest refuges in California vineyards 389 ABIOTIC AND BIOTIC PEST REFUGES HAMPER BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF MEALYBUGS IN CALIFORNIA VINEYARDS K.M. Daane,1 R. Malakar-Kuenen,1 M. Guillén,2 W.J. Bentley3, M. Bianchi,4 and D. González,2 1 Division of Insect Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California, U.S.A. 2 Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, California, U.S.A. 3 University of California Statewide IPM Program, Kearney Agricultural Center, Parlier, California, U.S.A. 4 University of California Cooperative Extension, San Luis Obispo, California, U.S.A. INTRODUCTION Four mealybug species cause economic damage in California vineyards. These are the grape mealy- bug, Pseudococcus maritimus (Ehrhorn); obscure mealybug, Pseudococcus viburni (Signoret); longtailed mealybug, Pseudococcus longispinus (Targioni-Tozzeti); and vine mealybug, Planococcus ficus (Signoret) (Godfrey et al., 2002). The grape, obscure, and longtailed mealybugs belong to the Pseudococcus maritimus-malacearum complex–a taxonomically close group of mealybugs (Wilkey and McKenzie, 1961). However, while the origins of the grape and longtailed mealybugs are believed to be in North America, the ancestral lines of the obscure mealybug are unclear. Regardless, these three species have been known as pests in North America for nearly 100 years. The vine mealybug, in contrast, was first identified in California in the Coachella Valley in the early 1990s (Gill, 1994). It has since spread into California’s San Joaquin Valley and central coast regions, with new infestations reported each year. The four species are similar in appearance; however, mealybugs in the P. maritimus- malacearum complex have longer caudal filaments than vine mealybug (Godfrey et al., 2002). -

Population Dynamic of the Long-Tailed

Assiut J. of Agric. Sci., 42 No.(5) (143-164) Population Dynamic of the Long-tailed Mealybug, Pseudococcus longispinus (Targioni-Tozzetti) Infest- ing the Ornamental Plant, Acalypha marginata Green, under Assiut governorate conditions. Ghada,S.Mohamed1; Abou-Ghadir,M.F.2; Abou- Elhagag,G.H.2 and Gamal H. Sewify3 1Dept. of plant protec., Fac. Agric., South Valley Univ. 2Dept. of plant protec., Fac. Agric., Assiut Univ. 3Dept. of plant protec., Fac. Agric., Cairo Univ. Abstract centages of parasitism ranged The shrubs of ornamental from 0.01 in January to 0.06% in plant were inspected as host of March and 0.007 to 0.05% in the the studied pest. The present same months during the first and study was carried out in the Ag- the second season of study. The riculture Experimental Station of seasonal abundance of this para- the Faculty of Agriculture, Assiut sitoid species and the effect of university, during two successive weather elements on its popula- seasons of 2008/2009 and tion were also studied. 2009/2010. Results of both sea- Introduction sons showed that the highest The ornamental plant, Aca- weekly population count of the lypha marginata is a common mealybug, Pesudococcus long- shrub planted for decoration ispinus (Targioni-Tozzetti) was along the streets. This plant is found during the 2rd half of Au- susceptible to the mealybug in- gust. The highest percentage of festation that cause a serious mal- the total monthly mean count was formation to its leaves. The also recorded during August common name of the mealy bugs (30% out of the total year is derived from the mealy wax count).The pest has four genera- secretion that usually covers their tions in each of the tow studied bodies (Kosztarab, 1996). -

Review of Ecologically-Based Pest Management in California Vineyards

insects Review Review of Ecologically-Based Pest Management in California Vineyards Houston Wilson 1,* and Kent M. Daane 2 ID 1 Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 2 Department Environmental Science, Policy and Management, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720-3114, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-559-646-6519 Academic Editors: Alberto Pozzebon, Carlo Duso, Gregory M. Loeb and Geoff M. Gurr Received: 28 July 2017; Accepted: 6 October 2017; Published: 11 October 2017 Abstract: Grape growers in California utilize a variety of biological, cultural, and chemical approaches for the management of insect and mite pests in vineyards. This combination of strategies falls within the integrated pest management (IPM) framework, which is considered to be the dominant pest management paradigm in vineyards. While the adoption of IPM has led to notable and significant reductions in the environmental impacts of grape production, some growers are becoming interested in the use of an explicitly non-pesticide approach to pest management that is broadly referred to as ecologically-based pest management (EBPM). Essentially a subset of IPM strategies, EBPM places strong emphasis on practices such as habitat management, natural enemy augmentation and conservation, and animal integration. Here, we summarize the range and known efficacy of EBPM practices utilized in California vineyards, followed by a discussion of research needs and future policy directions. EBPM should in no way be seen in opposition, or as an alternative to the IPM framework. Rather, the further development of more reliable EBPM practices could contribute to the robustness of IPM strategies available to grape growers. -

Evaluation of RNA Interference for Control of the Grape Mealybug Pseudococcus Maritimus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae)

insects Article Evaluation of RNA Interference for Control of the Grape Mealybug Pseudococcus maritimus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) Arinder K. Arora 1, Noah Clark 1, Karen S. Wentworth 2, Stephen Hesler 2, Marc Fuchs 3 , Greg Loeb 2 and Angela E. Douglas 1,4,* 1 Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA; [email protected] (A.K.A.); [email protected] (N.C.) 2 Department of Entomology, Cornell University, Geneva, NY 14456, USA; [email protected] (K.S.W.); [email protected] (S.H.); [email protected] (G.L.) 3 School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Geneva, NY 14456, USA; [email protected] 4 Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 19 September 2020; Accepted: 26 October 2020; Published: 28 October 2020 Simple Summary: RNA interference (RNAi) is a defense mechanism that protects insects from viruses by targeting and degrading RNA. This feature has been exploited to reduce the expression of endogenous RNA for determining functions of various genes and for killing insect pests by targeting genes that are vital for insect survival. When dsRNA matching perfectly to the target RNA is administered, the RNAi machinery dices the dsRNA into ~21 bp fragments (known as siRNAs) and one strand of siRNA is employed by the RNAi machinery to target and degrade the target RNA. In this study we used a cocktail of dsRNAs targeting grape mealybug’s aquaporin and sucrase genes to kill the insect. Aquaporins and sucrases are important genes enabling these insects to maintain water relations indispensable for survival and digest complex sugars in the diet of plant sap-feeding insects, including mealybugs. -

An Investigation Into the Integrated Pest Management of The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stellenbosch University SUNScholar Repository An investigation into the integrated pest management of the obscure mealybug, Pseudococcus viburni (Signoret) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae), in pome fruit orchards in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Pride Mudavanhu Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Agriculture (Entomology), in the Faculty of AgriSciences. at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Dr Pia Addison Department of Conservation Ecology and Entomology Faculty of AgriSciences University of Stellenbosch South Africa December 2009 DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the owner of the copyright thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. December 2009 Copyright © 2009 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i ABSTRACT Pseudococcus viburni (Signoret) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) (obscure mealybug), is a common and serious pest of apples and pears in South Africa. Consumer and regulatory pressure to produce commodities under sustainable and ecologically compatible conditions has rendered chemical control options increasingly limited. Information on the seasonal occurrence of pests is but one of the vital components of an effective and sustainable integrated pest management system needed for planning the initiation of monitoring and determining when damage can be expected. It is also important to identify which orchards are at risk of developing mealybug infestations while development of effective and early monitoring tools for mealybug populations will help growers in making decisions with regards to pest management and crop suitability for various markets. -

Transmission of Grapevine Leafroll-Associated Virus 3 (Glrav-3): Acquisition, Inoculation and Retention by the Mealybugs Planococcus Ficus and Pseudococcus Longispinus (Hemiptera

Transmission of Grapevine Leafroll-associated Virus 3 (GLRaV-3): Acquisition, Inoculation and Retention by the Mealybugs Planococcus ficus and Pseudococcus longispinus (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) K. Krüger1,*, D.L. Saccaggi1,3, M. van der Merwe2, G.G.F. Kasdorf2 (1) Department of Zoology & Entomology, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Pretoria, 0028, South Africa (2) ARC-Plant Protection Research Institute, Private Bag X134, Pretoria, 0001, South Africa (3) Current address: Plant Health Diagnostic Services, Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, Private Bag X5015, Stellenbosch, 7599, South Africa Submitted for publication: December 2014 Accepted for publication: March 2015 Key words: Ampelovirus, Closteroviridae, Coccoidea, grapevine leafroll disease, Vitis vinifera The vine mealybug, Planococcus ficus (Signoret), and the longtailed mealybug, Pseudococcus longispinus (Targioni Tozzetti), are vectors of grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 (GRLaV-3), one of the most abundant viruses associated with grapevine leafroll disease. To elucidate the transmission biology in South Africa, acquisition access periods (AAPs), inoculation access periods (IAPs) and the retention of the virus in starving and feeding first- to second instar nymphs were determined. The rootstock hybrid LN33 served as virus source and grapevines (Vitis vinifera L., cv. Cabernet franc) served as recipient plants. An AAP of 15 min or an IAP of 15 min was sufficient forPl. ficus to acquire or transmit GLRaV-3, respectively. Nymphs of Pl. ficus retained the virus for at least eight days when feeding on a non-virus host and grapevine, and for at least two days when starving, and were then capable of transmitting it successfully to healthy grapevine plants. Nymphs of Ps. longispinus transmitted the virus after an AAP of 30 min and an IAP of 1 h. -

Little Cherry Virus 1 & 2

WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Little Cherry Virus 1 & 2 Written by: Scott Harper, WSU Plant Pathology; Andrea Bixby Brosi, Betsy Beers, WSU Entomology; Tianna DuPont, WSU Extension. May 2019. Little Cherry Disease (LCD) is a critical concern to sweet cherry producers in the state of Washington. This disease is caused by infection by Little cherry virus 1 (LChV1), Little cherry virus 2 (LChV2) or the X-Disease Phytoplasma (Candidatus Phytoplasma pruni), and produces small, undersized cherries, with poor color development and flavor. Background Little Cherry Disease is not a new problem in the Pacific Figure 2 Little Cherry Virus 2 produces cherries of small size and poor Northwest. The first major epidemic occurred in the Kootenay color and flavor. Photo credit Andrea Bixby Brosi, WSU. valley in Canada in 1938, and over the following 40 years Little cherry virus (both -1 and-2) infection of sweet cherry devastated the Canadian cherry industry so much that by 1979 cultivars results in small fruit with reduced sugar content that the last packing line in the Kootenay valley closed, and the may taste bland or insipid. Severity of the disease differs Canadian industry has spent the last 40 years rebuilding. between cultivars, with Lambert and Bing being highly In Washington State the last major epidemic occurred in the late susceptible, whereas Van and Sam are less so and fruit may 1940s and into the 1950s, resulting in the removal of significant reach marketable size although flavor is still affected. On some acreage. But, with the passage of time and changes in cultivars such as Lambert, the fruit may also have a noticeable management practices, the disease has become prevalent in pointed tip. -

Season Studies of Cane Homoptera at Soledad, Cuba

II DRY--SEASON STUDIES OF CANE HOMOPTERA AT SOLEDAD, CUBA ;J. G~ MYERS -Issued Jun.e .14th 1926. ~ \~~ Reprinted from CoNTRIBUTIO~S FROM THE HARV ARD INSTITUTE FOR TROPICAL Brnr,oGY AND MEDICINE, VOLUME III. Without change of page numbers. DRY-SEASON STUDIES OF CANE HOMOPTERA AT SOLEDAD, CUBA, WITH A LIST OF THE COCCIDS OF THE DISTRICT J. G. MYERS 1851 Science Exhibiti.on Scholar for New Zealand, 19124 \ CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION . • • • • • • • • • 69 II. SUM.MARY OF PRESENT KNOWLEDGE OF CANE-MOSAIC TRANS- MISSION BY INSECTS . 70 III. THE MOSAIC SITUATION AT SOLEDAD 73 IV. THE FEEDING-HABITS OF HEMIPTERA IN GENERAL 74 v. THE CANE HoMoPTERA OF SOLEDAD. 77 1. List of Species 77 2. The Cicadellids . 79 3. The Cixiids. 84 4. The Delphacids 87 5. The Derbids 91 6. The Aphids 92 7. The Coccids 97 VI. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 100 APPENDIX I. DESCRIPTION OF Phaciocephalus cubanus n. sp •• 103 APPENDIX II. L1sT OF Coccrns OF SOLEDAD AND THEIR HosT-PLANTS 104 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • . • • . • . • . • . • • • • • • • • • 107 II DRY-SEASON STUDIES OF CANE HOMOPTERA AT SOLEDAD, CUBA l DRY-SEASON STUDIES OF CANE HOMOPTERA AT SOLEDAD, CUBA I. INTRODUCTION THE Hemiptera or true bugs, distinguished from all other in sects by their sucking mouth-parts and gradual metamorpho sis, have long been recognized as including a large proportion of injurious species, but it is only comparatively recently that their importance as carriers of dise~e has been established, while their interrelations as vectors of virus diseases of plants form the newest chapter in applied entomology. The leafhoppers, aphides, and scale-insects, or members of the suborder Homoptera, attacking sugar-cane, have sprung into prominence as carriers, possible, probable, or proved, of the mosaic disease of cane and other grasses. -

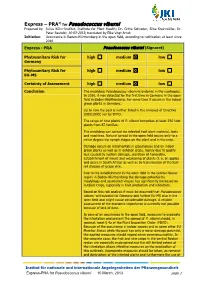

Express PRA Pseudococcus Viburni

1) Express – PRA for Pseudococcus viburni Prepared by: Julius Kühn-Institut, Institute for Plant Health; Dr. Gritta Schrader, Silke Steinmöller, Dr. Peter Baufeld; 10-03-2013; translated by Elke Vogt-Arndt Initiation: Occurrence in Baden-Württemberg in the open field, according to notification at least since 2010 Express - PRA Pseudococcus viburni (Signoret) Phytosanitary Risk for high medium low Germany Phytosanitary Risk for high medium low EU-MS Certainty of Assessment high medium low Conclusion The mealybug Pseudococcus viburni is endemic in the neotropics. In 2010, it was detected for the first time in Germany in the open field in Baden-Württemberg. For some time it occurs in the indoor green plants in Germany. Up to now the pest is neither listed in the annexes of Directive 2000/29/EC nor by EPPO. The range of host plants of P. viburni comprises at least 296 host plants from 87 families. The mealybug can spread via infested host plant material, tools and machines. Natural spread in the open field occurs only to a minor degree via nymph stages on the plant and in the crop. Damage occurs on ornamentals in glasshouses and on indoor green plants as well as in outdoor crops, mainly due to quality loss caused by suction damage, secretion of honeydew, establishment of mould and weakening of plants (f. e. on apples and pears in South Africa) as well as by transmission of the leaf- roll disease of grape vine. Due to the establishment in the open field in the central Neckar region in Baden-Württemberg the damage potential by mealybugs and associated viruses has significantly increased on outdoor crops, especially in fruit production and viticulture. -

Spatial Distribution of the Cottony Camellia Scale, Pulvinaria Floccifera (Westwood) (Hemiptera: Coccidae) in the Tea Orchards

JOURNAL OF PLANT PROTECTION RESEARCH Vol. 54, No. 1 (2014) DOI: 10.2478/jppr-2014-0007 Spatial distribution of the cottony camellia scale, Pulvinaria floccifera (Westwood) (Hemiptera: Coccidae) in the tea orchards Sakineh Naeimamini1, Habib Abbasipour1*, Sirus Aghajanzadeh2 1 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, Shahed University, 3319118651 Tehran, Iran 2 Citrus Research Institute of Iran, 49917 Ramsar, Iran Received: March 6, 2013 Accepted: January 20, 2014 Abstract: In the north of Iran, near the Caspian Sea, about 35,627 ha is cultivated with tea plant, Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze on both plain and hilly land. The cottony camellia scale, Pulvinaria floccifera (Westwood) (Hemiptera: Coccidae) is one of the most important pests of tea orchards in the north of Iran. Spatial distribution is an important item in entomoecology and needs to be studied for many pest management programs. So, weekly sampling of P. floccifera population was carried out throughout the 2008–2010 season, in the tea gardens of the Tonekabon region of the Mazandaran province of Iran. Each cut branch of tea was determined as a sample unit and after primary sampling, sample size was calculated using the equation: N = (ts/dm)2, (d = 0.15, sample size = 50). The data acquired were used to describe the spatial distribution pattern of P. floccifera by Tylor’s power law, Iwao’s mean crowding regression, Index of Dispersion (ID), and Index of Clumping (IDM). Tylor’s power law (R2 > 0.84) and Iwao’s mean crowding regression (R2 > 0.82) indi- cated that spatial distribution of 1st and 2nd nymphal instars is aggregated, but the distribution of 3rd instars, adults, and egg ovisacs is uniform. -

Checklist of the Scale Insects (Hemiptera : Sternorrhyncha : Coccomorpha) of New Caledonia

Checklist of the scale insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccomorpha) of New Caledonia Christian MILLE Institut agronomique néo-calédonien, IAC, Axe 1, Station de Recherches fruitières de Pocquereux, Laboratoire d’Entomologie appliquée, BP 32, 98880 La Foa (New Caledonia) [email protected] Rosa C. HENDERSON† Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170 Auckland Mail Centre, Auckland 1142 (New Zealand) Sylvie CAZÈRES Institut agronomique néo-calédonien, IAC, Axe 1, Station de Recherches fruitières de Pocquereux, Laboratoire d’Entomologie appliquée, BP 32, 98880 La Foa (New Caledonia) [email protected] Hervé JOURDAN Institut méditerranéen de Biodiversité et d’Écologie marine et continentale (IMBE), Aix-Marseille Université, UMR CNRS IRD Université d’Avignon, UMR 237 IRD, Centre IRD Nouméa, BP A5, 98848 Nouméa cedex (New Caledonia) [email protected] Published on 24 June 2016 Rosa Henderson† left us unexpectedly on 13th December 2012. Rosa made all our recent c occoid identifications and trained one of us (SC) in Hemiptera Sternorrhyncha slide preparation and identification. The idea of publishing this article was largely hers. Thus we dedicate this article to our late and dear Rosa. Rosa Henderson† nous a quittés prématurément le 13 décembre 2012. Rosa avait réalisé toutes les récentes identifications de cochenilles et avait formé l’une d’entre nous (SC) à la préparation des Hemiptères Sternorrhynques entre lame et lamelle. Grâce à elle, l’idée de publier cet article a pu se concrétiser. Nous dédicaçons cet article à notre chère et regrettée Rosa. urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:90DC5B79-725D-46E2-B31E-4DBC65BCD01F Mille C., Henderson R. C.†, Cazères S. & Jourdan H. 2016. — Checklist of the scale insects (Hemiptera: Sternorrhyncha: Coccomorpha) of New Caledonia. -

Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) Diversity in Received: 5 April 2017 Accepted: 1 November 2017 Southern Brazilian Fruit Crops Published: Xx Xx Xxxx Vitor C

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Integrative taxonomy methods reveal high mealybug (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) diversity in Received: 5 April 2017 Accepted: 1 November 2017 southern Brazilian fruit crops Published: xx xx xxxx Vitor C. Pacheco da Silva1, Mehmet Bora Kaydan2,3, Thibaut Malausa4, Jean-François Germain 5, Ferran Palero4,6 & Marcos Botton7 The Serra Gaúcha region is the most important temperate fruit-producing area in southern Brazil. Despite mealybugs (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) infesting several host plants in the region, there is a lack of information about the composition of species damaging diferent crops. A survey of mealybug species associated with commercial fruit crops (apple, persimmon, strawberry and grapes) was performed in Serra Gaúcha between 2013 and 2015, using both morphology and DNA analyses for species identifcation. The most abundant species were Pseudococcus viburni (Signoret), found on all four host plant species, and Dysmicoccus brevipes (Cockerell), infesting persimmon, vines and weeds. The highest diversity of mealybug species was found on persimmon trees, hosting 20 diferent taxa, of which Anisococcus granarae Pacheco da Silva & Kaydan, D. brevipes, Pseudococcus sociabilis Hambleton and Ps. viburni were the most abundant. A total of nine species were recorded in vineyards. Planococcus fcus (Signoret) and Pseudococcus longispinus (Targioni Tozzetti) were observed causing damage to grapes for the frst time. A single species, Ps. viburni, was found associated with apples, while both Ps. viburni and Ferrisia meridionalis Williams were found on strawberry. Four of the mealybug species found represent new records for Brazil. Brazil is the third largest fruit producer in the world, with a cultivated area of 2.5 million hectares and an esti- mated production of 40 million tons1,2.