Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iraq Coup of Raschid Ali in 1941, the Mufti Husseini and the Farhud

The Iraq Coup of 1941, The Mufti and the Farhud Middle new peacewatc document cultur dialo histor donation top stories books Maps East s h s e g y s A detailed timeline of Iraqi history is given here, including links to UN resolutions Iraq books Map of Iraq Map of Kuwait Detailed Map of Iraq Map of Baghdad Street Map of Baghdad Iraq- Source Documents Master Document and Link Reference for the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Zionism and the Middle East The Iraq Coup Attempt of 1941, the Mufti, and the Farhud Prologue - The Iraq coup of 1941 is little studied, but very interesting. It is a dramatic illustration of the potential for the Palestine issue to destabilize the Middle East, as well a "close save" in the somewhat neglected theater of the Middle East, which was understood by Churchill to have so much potential for disaster [1]. Iraq had been governed under a British supported regency, since the death of King Feysal in September 1933. Baqr Sidqi, a popular general, staged a coup in October 1936, but was himself assassinated in 1937. In December of 1938, another coup was launched by a group of power brokers known as "The Seven." Nuri al-Sa'id was named Prime Minister. The German Consul in Baghdad, Grobba, was apparently already active before the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, soliciting support for Germany and exploiting unrest. [2]. Though the Germans were not particularly serious about aiding a revolt perhaps, they would not be unhappy if it occurred. In March of 1940 , the "The Seven" forced Nuri al-Sa'id out of office. -

Britain and the Arab-Israeli War of 1948

Britainand the Arab Israeli War Downloaded from http://online.ucpress.edu/jps/article-pdf/16/4/50/161179/2536720.pdf by guest on 02 June 2020 of 1948 Avi Shlaim* At midnighton 14 May 1948, the Britishhigh commissioner for Palestineleft Palestine with all hisstaff, and twenty-eight years of British responsibilityfor Palestine came to an end. The storybegan with the BalfourDeclaration of November 1917 followed in April1920 by the San Remoconference's entrusting ofBritain with the Mandate for Palestine, so thatit wouldbe administeredaccording to the termsof the Balfour Declarationand preparedfor self-government. The way in whichthe mandatewas established left a terribleblot on Britain'sentire record as the greatpower responsible for governing the country. And therewas, to say theleast, something unusual about the way in which Britain retreated from themandate. As ReesWilliams, undersecretary ofstate for the colonies, toldthe House of Commons: "On the14th May, 1949, the withdrawal of theBritish Administration took place without handing over to a responsible authorityany of the assets, property or liabilitiesof the Mandatory Power. The mannerin whichthe withdrawal took place is unprecedentedin the historyof our Empire.' Whatwere the reasonsbehind the inexcusablyabrupt and reckless fashionin whichthe Britishgovernment chose to divestitself of the * Avi Shlaimis a Readerin Politicsat theUniversity of Reading, England. This paperwas preparedfor theconference on "BritishSecurity Policy 1945-1956" at King'sCollege, London, 25-26 March1987. The authorwould like to thankthe Economicand Social ResearchCouncil and the FordFoundation forresearch support. BRITAINAND THE ARAB-ISRAELIWAR OF 1948 51 Mandatefor Palestine? Very different answers are givento thisquestion by thetwo nations most directly affected by the British decision. On theJewish sidethe predominant view is thatBritain departed with full knowledge that the surroundingArab countrieswould immediatelyattack and in the expectationthat the Jewish population of Palestinewould be massacredor driveninto the sea. -

The Rise and Fall of the All-Palestine Government in Gaza

The Rise and Fall of the All Palestine Government in Gaza Avi Shlaim* The All-Palestine Government established in Gaza in September 1948 was short-lived and ill-starred, but it constituted one of the more interest- ing and instructive political experiments in the history of the Palestinian national movement. Any proposal for an independent Palestinian state inevitably raises questions about the form of the government that such a state would have. In this respect, the All-Palestine Government is not simply a historical curiosity, but a subject of considerable and enduring political relevance insofar as it highlights some of the basic dilemmas of Palestinian nationalism and above all the question of dependence on the Arab states. The Arab League and the Palestine Question In the aftermath of World War II, when the struggle for Palestine was approaching its climax, the Palestinians were in a weak and vulnerable position. Their weakness was clearly reflected in their dependence on the Arab states and on the recently-founded Arab League. Thus, when the Arab Higher Committee (AHC) was reestablished in 1946 after a nine- year hiatus, it was not by the various Palestinian political parties them- selves, as had been the case when it was founded in 1936, but by a deci- sion of the Arab League. Internally divided, with few political assets of its *Avi Shlaim is the Alastair Buchan Reader in International Relations at Oxford University and a Professorial Fellow of St. Antony's College. He is author of Collusion Across the Jordan: King Abdullah the Zionist Movement and the Partition of Palestine (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988). -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 48

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 48 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2010 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All ri hts reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information stora e and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group ,indrush House Avenue Two Station Lane ,itney O028 40, 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President 2arshal of the Royal Air Force Sir 2ichael 3eetham GC3 C3E DFC AFC 7ice8President Air 2arshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KC3 C3E AFC Committee Chairman Air 7ice82arshal N 3 3aldwin C3 C3E FRAeS 7ice8Chairman -roup Captain 9 D Heron O3E Secretary -roup Captain K 9 Dearman FRAeS 2embership Secretary Dr 9ack Dunham PhD CPsychol A2RAeS Treasurer 9 Boyes TD CA 2embers Air Commodore - R Pitchfork 23E 3A FRAes :9 S Cox Esq BA 2A :6r M A Fopp MA F2A FI2 t :-roup Captain A 9 Byford MA MA RAF :,ing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF ,ing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications ,ing Commander C G Jefford M3E BA 2ana er :Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS OPENIN- ADDRESS œ Air 2shl Ian Macfadyen 7 ON.Y A SIDESHO,? THE RFC AND RAF IN A 2ESOPOTA2IA 1914-1918 by Guy Warner THE RAF AR2OURED CAR CO2PANIES IN IRAB 20 C2OST.YD 1921-1947 by Dr Christopher Morris No 4 SFTS AND RASCHID A.IES WAR œ IRAB 1941 by )A , Cdr Mike Dudgeon 2ORNIN- Q&A F1 SU3STITUTION OR SU3ORDINATION? THE E2P.OY8 63 2ENT OF AIR PO,ER O7ER AF-HANISTAN AND THE NORTH8,EST FRONTIER, 1910-1939 by Clive Richards THE 9E3E. -

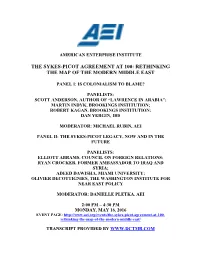

The Sykes-Picot Agreement at 100: Rethinking the Map of the Modern Middle East

AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE THE SYKES-PICOT AGREEMENT AT 100: RETHINKING THE MAP OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST PANEL I: IS COLONIALISM TO BLAME? PANELISTS: SCOTT ANDERSON, AUTHOR OF “LAWRENCE IN ARABIA”; MARTIN INDYK, BROOKINGS INSTITUTION; ROBERT KAGAN, BROOKINGS INSTITUTION; DAN YERGIN, IHS MODERATOR: MICHAEL RUBIN, AEI PANEL II: THE SYKES-PICOT LEGACY, NOW AND IN THE FUTURE PANELISTS: ELLIOTT ABRAMS, COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS; RYAN CROCKER, FORMER AMBASSADOR TO IRAQ AND SYRIA; ADEED DAWISHA, MIAMI UNIVERSITY; OLIVIER DECOTTIGNIES, THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY MODERATOR: DANIELLE PLETKA, AEI 2:00 PM – 4:30 PM MONDAY, MAY 16, 2016 EVENT PAGE: http://www.aei.org/events/the-sykes-picot-agreement-at-100- rethinking-the-map-of-the-modern-middle-east/ TRANSCRIPT PROVIDED BY WWW.DCTMR.COM MICHAEL RUBIN: Welcome to the American Enterprise Institute and our panel on Sykes-Picot at 100. I want to thank you all for being here. Of course, anniversaries matter, and this is one of the most significant anniversaries at least in the crafting of the modern Middle East. Now, the Sykes-Picot Agreement may not have been implemented as it was originally designed, but few would doubt that it has had tremendous impact on the eventual shaping of the Middle East. And I’m thrilled that we have a two-panel conference. Danielle Pletka, the vice president for foreign policy and defense at AEI, will moderate the second panel, but I’ll be talking a little bit about the history panel. My name is Michael Rubin. I’m a resident scholar here. I’m a historian by training, which means I get paid to predict the past. -

Bartosz Wróblewski1 Systemic Transformations in Jordan in 1951

Przegląd Prawa Konstytucyjnego -----ISSN 2082-1212----- DOI 10.15804/ppk.2020.06.41 -----No. 6 (58)/2020----- Bartosz Wróblewski1 Systemic Transformations in Jordan in 1951– 1957 – Unsuccessful Democracy Keywords: Jordan, the Hashemite, liberalization, Chamber of Deputies, parliament Słowa kluczowe: Jordania, Haszymidzi, liberalizacja, Izba Deputowanych, parlament Abstract The following text discusses the first attempt to transform the authoritarian Jordan mon- archy into a constitutional monarchy, in which the parliament chosen by the people was supposed, apart from the king, to serve the role of a real supervisor of the state. Such an attempt was made in 1951–1957. It ended up in a failure and, in fact, the return of the au- thoritarian methods of exercising the power. This failure resulted both from the specific circumstances of the contemporary Middle East, as well as certain permanent features of Arabic societies. Thus, it is important to trace back these events to show both the at- tempt at reforms, as well as the causes of the failure. The following text makes use first and foremost of English language resources con- cerning the history of Jordan. Also, the archive documents collected in the National Ar- chives were used, especially the ones that refer to the correspondence between the au- thorities in London and the British embassy in Amman. To understand the issue, it will be necessary to go back beyond the year 1951 and to present in brief the very process of how the Hashemite monarchy came into existence. 1 ORCID ID: 0000-0003-4436-8221, Assoc. Prof., Department of International Rela- tions and Human Rights, Institute of Political Science, College of Social Sciences, University of Rzeszow. -

Legacies of the Anglo-Hashemite Relationship in Jordan

Legacies of the Anglo-Hashemite Relationship in Jordan: How this symbiotic alliance established the legitimacy and political longevity of the regime in the process of state-formation, 1914-1946 An Honors Thesis for the Department of Middle Eastern Studies Julie Murray Tufts University, 2018 Acknowledgements The writing of this thesis was not a unilateral effort, and I would be remiss not to acknowledge those who have helped me along the way. First of all, I would like to thank my advisor, Professor Thomas Abowd, for his encouragement of my academic curiosity this past year, and for all his help in first, making this project a reality, and second, shaping it into (what I hope is) a coherent and meaningful project. His class provided me with a new lens through which to examine political history, and gave me with the impetus to start this paper. I must also acknowledge the role my abroad experience played in shaping this thesis. It was a research project conducted with CET that sparked my interest in political stability in Jordan, so thank you to Ines and Dr. Saif, and of course, my classmates, Lensa, Matthew, and Jackie, for first empowering me to explore this topic. I would also like to thank my parents and my brother, Jonathan, for their continuous support. I feel so lucky to have such a caring family that has given me the opportunity to pursue my passions. Finally, a shout-out to the gals that have been my emotional bedrock and inspiration through this process: Annie, Maya, Miranda, Rachel – I love y’all; thanks for listening to me rant about this all year. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France. -

The Baghdad Set

The Baghdad Set Also by Adrian O’Sullivan: Nazi Secret Warfare in Occupied Persia (Iran): The Failure of the German Intelligence Services, 1939–45 (Palgrave, 2014) Espionage and Counterintelligence in Occupied Persia (Iran): The Success of the Allied Secret Services, 1941–45 (Palgrave, 2015) Adrian O’Sullivan The Baghdad Set Iraq through the Eyes of British Intelligence, 1941–45 Adrian O’Sullivan West Vancouver, BC, Canada ISBN 978-3-030-15182-9 ISBN 978-3-030-15183-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15183-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019934733 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive licence to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the pub- lisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 19 March 2010

United Nations A/HRC/13/NGO/138 General Assembly Distr.: General 19 March 2010 English only Human Rights Council Thirteenth session Agenda items 7 and 9 Human rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories Racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related forms of intolerance, follow-up and implementation of the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action Written statement* submitted by the World Union for Progressive Judaism (WUPJ), a non-governmental organization on the roster The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [14 March 2010] * This written statement is issued, unedited, in the language(s) received from the submitting non- governmental organization(s). GE.10-12320 A/HRC/13/NGO/138 Palestine Partition Plans (1922 & 1947): Right to the Truth on Refugees 1. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 [II], the second ‘Partition Plan’ of the Mandatory area of Palestine. The aim was to divide the land west of the river Jordan into “independent Arab and Jewish States” within the remaining area – roughly 23 percent of the designated League of Nations Palestine area of 120,000 km², with Jerusalem as a corpus separatum administered directly by the United Nations. 2. In 1922, all the League of Nations designated area east of the Jordan river (about 77 percent, 94,000 km² of Palestine) was offered to Britain’s World War I ally, the Emir Abdullah (exiled by the Saudis from Arabia), thus creating a de facto Hashemite Emirate of Trans-Jordan, which declared its independence in 1946. -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62923-9 — Glubb Pasha and the Arab Legion Graham Jevon Excerpt More Information 1 Introduction Throughout the twenty- fi rst century, and much of the twentieth, confl ict in the Middle East has dominated the international news headlines. Since the 2011 uprisings, popularly referred to as the Arab Spring, different parts of the region have almost taken it in turns to lead the international segments of Western news media broadcasts: Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Gaza, Syria, and Iraq have all had their moment in the spotlight. Jordan, though, has remained largely overlooked, except, if you listen carefully, as a location on which refugees have descended from other states that have dominated the headlines, such as Palestine, Syria, and Iraq. This hints at Jordan’s centrality, if only geographically. However, Jordan’s apparent absence within the international current affairs con- sciousness belies its centrality to the politics of the region, particularly its historical signifi cance in relation both to the Arab– Israeli confl ict and to Britain’s imperial moment in the Middle East. The purpose of this book is to unpack Jordan’s pivotal relationship to these two critical issues during what is arguably the most crucial decade in the history of the Arab world. 1 Based on signifi cant new sources, this study provides an analysis of the post–Second World War role of the Arab Legion – the Jordanian Army, as it was known until 1956 – and its British commander, John Bagot Glubb – more commonly known as Glubb Pasha. This is not a history of Jordan. -

Iraq Tribal Study – Al-Anbar Governorate: the Albu Fahd Tribe

Iraq Tribal Study AL-ANBAR GOVERNORATE ALBU FAHD TRIBE ALBU MAHAL TRIBE ALBU ISSA TRIBE GLOBAL GLOBAL RESOURCES RISK GROUP This Page Intentionally Left Blank Iraq Tribal Study Iraq Tribal Study – Al-Anbar Governorate: The Albu Fahd Tribe, The Albu Mahal Tribe and the Albu Issa Tribe Study Director and Primary Researcher: Lin Todd Contributing Researchers: W. Patrick Lang, Jr., Colonel, US Army (Retired) R. Alan King Andrea V. Jackson Montgomery McFate, PhD Ahmed S. Hashim, PhD Jeremy S. Harrington Research and Writing Completed: June 18, 2006 Study Conducted Under Contract with the Department of Defense. i Iraq Tribal Study This Page Intentionally Left Blank ii Iraq Tribal Study Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY CHAPTER ONE. Introduction 1-1 CHAPTER TWO. Common Historical Characteristics and Aspects of the Tribes of Iraq and al-Anbar Governorate 2-1 • Key Characteristics of Sunni Arab Identity 2-3 • Arab Ethnicity 2-3 – The Impact of the Arabic Language 2-4 – Arabism 2-5 – Authority in Contemporary Iraq 2-8 • Islam 2-9 – Islam and the State 2-9 – Role of Islam in Politics 2-10 – Islam and Legitimacy 2-11 – Sunni Islam 2-12 – Sunni Islam Madhabs (Schools of Law) 2-13 – Hanafi School 2-13 – Maliki School 2-14 – Shafii School 2-15 – Hanbali School 2-15 – Sunni Islam in Iraq 2-16 – Extremist Forms of Sunni Islam 2-17 – Wahhabism 2-17 – Salafism 2-19 – Takfirism 2-22 – Sunni and Shia Differences 2-23 – Islam and Arabism 2-24 – Role of Islam in Government and Politics in Iraq 2-25 – Women in Islam 2-26 – Piety 2-29 – Fatalism 2-31 – Social Justice 2-31 – Quranic Treatment of Warfare vs.