Mccrae's Battalion: the Story of the 16Th Royal Scots (Review) Jeremy A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, I MARCH, 1945

Il82 SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, i MARCH, 1945 No..' 6100031 (Lance-Sergeant Eric Francis Aubrey No. 6977405 Private Thomas Dawson, The King's Upperton, The Green Howards (Alexandra, Own Scottish Borderers (Kells, Co. Meath). Princess of Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment) No. 14244985 Private (acting Corporal) Mathew (High Wycombe). Lawrence Morgan, The Cameromans (Scottish No. 14655457 Lance-Corporal John Wilks, The Green Rifles). Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own No. 5182405 Corporal (acting Sergeant) Albert Victor Yorkshire Regiment) (Scunthorpe). Walker, The Gloucestershire Regiment (Water- No. 58189820 Private Harold Gmntham Birch, The moore, Glos). Green Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's No. 5258245 Sergeant John Isaac Gue'st, The Own Yorkshire Regiment). Worcestershire Regiment (Worcester). No. 144274180 Private James Alfred Reddington, No. 4982401 Sergeant William Francis Jennings, The The Green Howards (Alexandra, 'Princess of Worcestershire Regiment (London, £.14). Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment) (Deal). No. 5257827 Lance-Corporal Alfred Henry Palmer, No. 5388512 Private Frederick James Riddle, The The Worcestershire Regiment (Redditch). Green Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's No. 5257681 Private George Bromwich, The ' Own "Yorkshire Regiment) (ChaMont-St.-Giles). Worcestershire Regiment (Rugby). No. 3772811 Sergeant George Bannerman, The Royal No. 5436899 Private Reginald Lugg, The Worcester- Scots Fusiliers (Nottingham). shire Regiment (Reading). No. 3125986 Sergeant Albert Shires, The Royal No. 14419045 Private Arthur Edwin Stacey, The Scots Fusiliers (iHartlepool). Worcestershire Regiment (Shaftesbury). No. 3775276 Corporal (acting Sergeant) William No. 3380*595 Warrant Officer Class I Ernest William Beagan, The Royal Scots Fusiliers (Liverpool 4). Churchill, The East Lancashire Regiment No. 3134048 Corporal (acting Sergeant) William John (tAlnwick). -

Private Arthur Phillip FLUNDER Service Number: 16708 11Th Battalion (Cambridge Pals) the Suffolk Regiment Died 1St July 1916

Private Arthur Phillip FLUNDER Service Number: 16708 11th Battalion (Cambridge Pals) The Suffolk Regiment Died 1st July 1916 Commemorated on Thiepval Memorial Pier and face 1C and 2A WW1 Centenary record of an Unknown Soldier Recruitment – 11th Battalion Suffolk Regiment – Suffolks/Cambs – (Cambridge Pals) Private Arthur FLUNDER was a member of the 11th Suffolks, which was a service battalion known as the Cambs/Suffolks or Cambridge Pals. At the outbreak of the war, men of the County enlisting for Infantry were sent to the Suffolk Regiment Depot at Bury St Edmunds. This soon became overcrowded and a relief camp was formed in Cambridge. Battle of the Somme The plan was for the British forces to attack on a fourteen-mile front after an intense week-long artillery bombardment of the German positions. Over 1.6 million shells were fired, 70 for every one metre of front, the idea being to decimate the German Front Line. Two minutes before zero-hour, 19 mines were exploded under the German lines. Whistles sounded and the troops went over the top at 7.30am. They advanced in lines at a slow, steady pace across No Man's Land towards then German front line. Objective 9 – La Boisselle – The Somme - See fig 1. Attack on La Boisselle Private Arthur FLUNDER and the 11th Suffolks were assigned Objective 9, an attack on the village of La Boisselle. The village of La Boisselle was of huge strategic importance as it would open up the road to Bapaume. This would allow the Allies to attack Poziers, the next town further up the road then from there, Thiepval. -

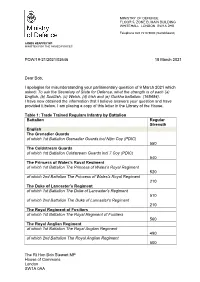

The Rt Hon Bob Stewart MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA PQW

MINISTRY OF DEFENCE FLOOR 5, ZONE B, MAIN BUILDING WHITEHALL LONDON SW1A 2HB Telephone 020 7218 9000 (Switchboard) JAMES HEAPPEY MP MINISTER FOR THE ARMED FORCES PQW/19-21/2021/02646 18 March 2021 Dear Bob, I apologise for misunderstanding your parliamentary question of 9 March 2021 which asked: To ask the Secretary of State for Defence, what the strength is of each (a) English, (b) Scottish, (c) Welsh, (d) Irish and (e) Gurkha battalion. (165484). I have now obtained the information that I believe answers your question and have provided it below. I am placing a copy of this letter in the Library of the House. Table 1: Trade Trained Regulars Infantry by Battalion Battalion Regular Strength English The Grenadier Guards of which 1st Battalion Grenadier Guards incl Nijm Coy (PDIC) 550 The Coldstream Guards of which 1st Battalion Coldstream Guards incl 7 Coy (PDIC) 540 The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment 520 of which 2nd Battalion The Princess of Wales's Royal Regiment 210 The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment 510 of which 2nd Battalion The Duke of Lancaster's Regiment 210 The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers of which 1st Battalion The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers 560 The Royal Anglian Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment 490 of which 2nd Battalion The Royal Anglian Regiment 500 The Rt Hon Bob Stewart MP House of Commons London SW1A 0AA The Yorkshire Regiment of which 1st Battalion The Yorkshire Regiment 510 -

The History of the Second Dragoons : "Royal Scots Greys"

Si*S:i: \ l:;i| THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND DRAGOONS "Royal Scots Greys" THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND DRAGOONS 99 "Royal Scots Greys "•' •••• '-•: :.'': BY EDWARD ALMACK, F.S.A. ^/>/4 Forty-four Illustrations LONDON 1908 ^7As LIST OF SUBSCRIBERS. Aberdeen University Library, per P. J. Messrs. Cazenove & Son, London, W.C. Anderson, Esq., Librarian Major Edward F. Coates, M.P., Tayles Edward Almack, Esq., F.S.A. Hill, Ewell, Surrey Mrs. E. Almack Major W. F. Collins, Royal Scots Greys E. P. Almack, Esq., R.F.A. W. J. Collins, Esq., Royal Scots Greys Miss V. A. B. Almack Capt. H.R.H. Prince Arthur of Con- Miss G. E. C. Almack naught, K.G., G.C.V.O., Royal Scots W. W. C. Almack, Esq. Greys Charles W. Almack, Esq. The Hon. Henry H. Dalrymple, Loch- Army & Navy Stores, Ltd., London, S.W. inch, Castle Kennedy, Wigtonshire Lieut.-Col. Ash BURNER, late Queen's Bays Cyril Davenport, Esq., F.S.A. His Grace The Duke of Atholl, K.T., J. Barrington Deacon, Esq., Royal etc., etc. Western Yacht Club, Plymouth C. B. Balfour, Esq. Messrs. Douglas & Foulis, Booksellers, G. F. Barwick, Esq., Superintendent, Edinburgh Reading Room, British Museum E. H. Druce, Esq. Lieut. E. H. Scots Bonham, Royal Greys Second Lieut. Viscount Ebrington, Royal Lieut. M. Scots Borwick, Royal Greys Scots Greys Messrs. Bowering & Co., Booksellers, Mr. Francis Edwards, Bookseller, Lon- Plymouth don, W. Mr. W. Brown, Bookseller, Edinburgh Lord Eglinton, Eglinton Castle, Irvine, Major C. B. Bulkeley-Johnson, Royal N.B. Scots Greys Lieut. T. E. Estcourt, Royal Scots Greys 9573G5 VI. -

Regimental Collects Before Your Path, and Make You Ready to Meet Him When He Comes in Glory; and the Blessing

Seasonal Blessings Advent Christ the Sun of Righteousness shine upon you, scatter the darkness from Regimental Collects before your path, and make you ready to meet him when he comes in glory; and the blessing . The Life Guards Christmas O Everliving God, King of Kings, in whose service we put on the breastplate of May the joy of the angels, the eagerness of the shepherds, the perseverance of faith and love, and for a helmet the hope of salvation, grant we beseech thee the wise men, the obedience of Joseph and Mary, and the peace of the Christ that The Life Guards may be faithful unto death, and at last receive the crown child be yours this Christmas; and the blessing . of life from Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen. Epiphany The Blues and Royals Christ the Son of God perfect in you the image of his glory and gladden your O Lord Jesus Christ who by the Holy Apostle has called us to put on the hearts with the good news of his kingdom; and the blessing . armour of God and to take the sword of the spirit, give thy grace we pray thee, Lent to the Blues and Royals that we may fight manfully under thy banner against all Christ give you grace to grow in holiness, to deny yourselves, take up your evil, and waiting on thee to renew our strength, may mount up with wings as cross, and follow him; and the blessing and the blessing . eagles, in thy name, who livest and reignest with the Father and the Holy Ghost, ever one God, world without end. -

Regiment Col/Pan Face Welch Regiment Col 1 N Loyal North Lancashire Regiment Col 1 S Suffolk Regiment Col 1 W Green Howards

Regiment Col/Pan Face Welch Regiment Col 1 N Loyal North Lancashire Regiment Col 1 S Suffolk Regiment Col 1 W Green Howards Col 2 E Bedfordshire Regiment Col 2 N Royal Welsh Fusiliers Col 2 S South Wales Borderers Col 2 W Royal Berkshire Regiment Col 3 E Seaforth Highlanders Col 3 N Royal Irish Regiment Col 3 S Worcestershire Regiment Col 3 W Cameronians Col 4 E Gloucestershire Regiment Col 4 N Manchester Regiment Col 4 S Border Regiment Col 4 W Queen's Own [Royal West Kent Regiment] Col 5 E Lincolnshire Regiment Col 5 N King's Own Yorkshire Light infantry Col 5 S East Lancashire Regiment Col 5 W Devonshire Regiment Col 6 E Royal Munster Fusiliers Col 6 N Connaught Rangers Col 6 S Royal Irish Fusiliers Col 6 W West Yorkshire Regiment Col 7 E Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers Col 7 N Royal Sussex Regiment Col 7 S Leicestershire Regiment Col 7 W Royal Irish Rifles Pan 8 E South Staffordshire Regiment Pan 9 E York and Lancaster Regiment Col 10 E Prince of Wales Volunteers [S. Lancashire] Col 10 N King's Regiment [Liverpool] Col 10 S Prince of Wales North Staffordshire Regiment Col 10 W Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry Col 11 E Durham Light Infantry Col 11 N Northamptonshire Regiment Col 11 S Buffs [East Kent Regiment] Col 11 W King's Own Scottish Borderers Col 12 E Dorsetshire Regiment Col 12 N Norfolk Regiment Col 12 S Wiltshire Regiment Col 12 W Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders Col 13 E Black Watch Col 13 N Gordon Highlanders Col 13 S Highland Light Infantry Col 13 W Queen's Royal Regiment Col 14 E Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders -

THE 24Th REGIMENTS LINKS with the COUNTY of WARWICKSHIRE

THE 24th REGIMENT’S LINKS WITH THE COUNTY OF WARWICKSHIRE. A revision of the article of the same name from the Journal of the Anglo Zulu War Historical Society, June 1997. (Inaugural Edition). By Derrick Smart __________________________________________________________________________________ ‘Regiments are raised in troubled times’. The birth of the 24th Regiment was in accordance with this dictum. In the early months of 1689 William and Mary newly arrived from Holland, reigned uneasily over a country still recovering from James II’s determined bid to regain the throne of England in the revolution of 1688. That revolution led to war with Louis X1V’s France (Louis had championed the ill-fated James); and to fight the war it was necessary to provide troops. King William as was the custom of the times, sent off Commissions to the noblemen and landowners who supported his cause. One such Commission went to Sir Edward Dering, 3rd Baronet, of Surrenden in Kent. The Commission was acted upon at once. It was dated 8th March 1689 and by 28th March, the first muster was held and Dering’s Regiment became part of the Standing Army and thereafter named after the Colonel (1). The Royal Warrant of 1st July 1751 listing precedence gave the Regiment seniority as the 24th Regiment of Foot. The 24th formed a 2nd Battalion in Lincolnshire in 1756, which was used in 1758 to form the 69th Regiment of Foot. In 1782 they were re-titled as the 69th (South Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot. The 24th Regiment’s 2nd Battalion was re-formed in Warwick in 1804 being disbanded in 1814. -

The Pipes and Drums of the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers and Greys)

The Pipes and Drums of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (Carabiniers and Greys) The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards are Scotland`s senior regiment and only regular cavalry regiment. The Regiment was formed in 1971 from the amalgamation of the 3rd Carabiniers (whom were themselves the result of the amalgamation of the 6th Dragoon Guards the Carabiniers and the 3rd the Prince of Wales Dragoon Guards in 1922) and The Royal Scots Greys (2nd Dragoons). The history of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards is therefore the record of three ancient regiments. Through The Royal Scots Greys, whose predecessors were raised by King Charles II in 1678 the Regiment can claim to be the oldest surviving Cavalry of the Line in The British Army. Displayed on the Regimental Standard are just fifty of the numerous battle honours won in wars and campaigns spanning three centuries. The most celebrated of these are Waterloo, Balaklava and Nunshigum. At the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 the Scots Greys took part in the famous Charge of the Union Brigade. It was here that Sergeant Ewart captured the Imperial Eagle, the Standard of Napoleon`s 45th Regiment. This standard is now displayed in the Home Headquarters of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards at Edinburgh Castle and in commemoration the Eagle forms part of The Royal Scots Dragoon Guards cap badge. During the Crimean War in 1854 two Victoria Crosses were awarded at the Battle of Balaklava against the Russians in the famous Charge of the Heavy Brigade. In World War II the battle honour Nunshigum was won by B Squadron of the 3rd Carabiniers against the Japanese in Burma. -

Organization of the Divisions of the British Army August-December 1914

Organization of the Divisions of the British Army August-December 1914 1st Division: (August 1914) 1st Guards Brigade 1st Cold Stream Guards 1st Scots Guard 1st Black Watch 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers 2nd Brigade 2/Royal Sussex 2/Loyal North Lancashire 1/Northumberland 1/King's Royal Rifle Corps 3rd Brigade 1/Queen's 1/South Wales Borderers 1/Gloucester 2/Welsh Mounted Troops: C Sqdn. 15/Hussars 1st Cyclist Company XXV Artillery Brigade: 113th Battery 114th Battery 115th Battery XXVI Artillery Brigade: 116th Battery 117th Battery 118th Battery1 XXXIX Artillery Brigade: 46th Battery 51st Battery 54th Battery XLIII Artillery Brigade: 30th (H.) Battery 40th (H.) Battery 57th (H.) Battery2 Brigade Ammunition Columns: XXV B.A.C. XXVI B.A.C. XXXIX B.A.C. XLII (H.) B.A.C. Heavy Battery: 26th Heavy Battery & Heavy Battery A.C. Divisional Ammunition Columns: 1st D.A.C. 1 Transferred to 28th Division on 2/4/15. 2 Joined brigade on 4/20/15. 1 Engineer Field Companies: 23rd & 26th Divisional Signals Companies: 1st Field Ambulances: 1st, 2nd, & 3rd Mobile Veterinary Sections: 2nd Divisional Train: 1st 2nd Division: (August 1914) 4th (Guards) Brigade3 2nd Grenadier Guards 2nd Coldstream Guards 3rd Coldstream Guards 1/Irish Guards 5th Brigade 2/Worcester 2/Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Light Infantry 2/Highland Light Infantry 2/Connaught Rangers4 6th Brigade 1/King's 2/South Staffordshire 1/Royal Berkshire 1/King's Royal Rifle Corps Mounted Troops: B Sqn, 15th Hussars5 2nd Cyclist Company XXXIV Artillery Brigade: 22nd Battery6 50th Battery 70th Battery XXXVI Artillery Brigade: 15th Battery 48th Battery 71st Battery XLI Artillery Brigade: 9th Battery 16th Battery 17th Battery XLIV (H.) Artillery Brigade: 47th Battery (H.) 3 Transferred to Guards Division on 8/19/15. -

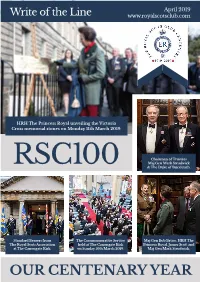

April 2019 Write of the Line

April 2019 Write of the Line www.royalscotsclub.com HRH The Princess Royal unveiling the Victoria Cross memorial stones on Monday 11th March 2019. Chairman of Trustees Maj Gen Mark Strudwick RSC100 & The Duke of Buccleuch. Standard Bearers from The Commemorative Service Maj Gen Bob Bruce, HRH The The Royal Scots Association held at The Canongate Kirk Princess Royal, James Scott and at The Canongate Kirk. on Sunday 10th March 2019. Maj Gen Mark Strudwick. OUR CENTENARY YEAR From the Chairman Colonel Clinton Hicks OBE The Club centenary year began in earnest on Sunday 10th March with a service at Canongate Kirk. The Reverend Neil Gardner officiated and the Lowland Band of the Royal Regiment of Scotland played throughout. Standard bearers from The Royal Scots Association provided a colourful backdrop at the Kirk. Lunch then followed at the Club. The following day The Princess Royal, our Patron, was present at a ceremony at the Club to launch the Club centenary book by Mr Roddy Martine “Not for Riches, Nor Glory, One Hundred Years of The Royal Scots Club”. If you have yet to obtain your copy of this book I strongly urge you to do so – it is an excellent read. Her Royal Highness also unveiled eight memorial stones to commemorate those Royal Scots awarded the Victoria Cross. Seven were awarded during the Great War and one was awarded during the Crimean War. The stones can be seen set into the paving just outside the Club main entrance. On Thursday 28th March the Trustees held a Founders Dinner for members and invited guests. -

THE LONDON Liazette, 26 MAY, 1916, 5223

THE LONDON liAZETTE, 26 MAY, 1916, 5223 IST RE-PUBLICATION of LIST CCCCLXXXIII of the Names of deceased Soldiers whose Personal- Estate is held for distribution amongst the Next of Kin or others entitled.—Effects 1914-15. Name. Rank. Regiment, &c. Amount. £ s. d. Aitchison, A. ,.*.• Private 1st Battalion Duke of Cornwall's 4 15 10 Light Infantry Allan, J. , Private 2nd Battalion Royal Scots 15 1 5 Ay res, W. T. Private 12th Reserve Regiment of Cavalry .. 1 2 11 Barclay, J Private 2nd Battalion Highland Light Infantry 576 Barlow, J. W. Private 9th Lancers 3 12 4 Bartlett, W. G Private 1st Battalion Cheshire Regiment 5 11 7 Beecher, J Private 1st Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers .. 4 17 6 Bell, C Private 2nd Battalion King's Royal Rifle Corps 3 11 6 Blair, J Private 2nd Battalion Seaforth Highlanders 1 13 5 Boon, T. J Driver 119th Battery Royal Field Artillery 1 15 9 Boyle, J. Private 2nd Bn. Highland Light Infantry .. 0 11 6 Brown, J Bandsman 1st Battalion Cameron Highlanders.. 213 Byrne, H Corporal 1st Battalion Royal Dublin Fusiliers 20 16 1 Carlisle, H Private 1st Battalion Irish Guards ... 4 19 4 Carroll, W.. Corporal 114th Battery Royal Field Artillery 17 16 3 Cheetham, J Private 2nd Bn. South Staffordshire Regiment 478 Cole, C. H Private 2nd Battalion King's Own York- 11 14 11 shire Light Infantry Crowley, P Private 3rd Battalion Rifle Brigade 2 14 2 Cullum, J. S. Private 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards 6 13 7 Cutler, T. W. Private 1st Bn. East Surrey Regiment 6 10 4 Davey, H Driver No. -

Soldiers in 1916

Soldiers in 1916 Surname Full Name Regiment, Date in Page number battalion newspaper ? Pt Joe Manchester Regiment 02 September 7 in order of page ? Pr Reg? 02 September 6 in order of pages ? Harry ?. ON FURLOUGH 17 June 6 ? 20 Names Prisoners Of War 22 January 7 ? Private Samuel ? 18th Battalion 15 January 5 Middlesex ? General H.Q. Staff- 4 names Local Men Honoured. 08 January 5 Manchester Regiment.- 15 names Click on above and scroll Manchester Regiment 'Service down. Battalion' 6 names. Cheshire Regiment- 5 names Cheshire Regiment- (T.F.) 6 names Cheshire Regiment Service Battalion Adams Sapper T Adams 23 January 5, in order of pages Addison Pt H. Addison 2nd Manchester 22 July 6 Regiment Ainley Pt William Ainley Cheshire Regiment 26 August 5 in order of pages Aitken Sir Max Aitken 01 July 4 Aitken Sir Max Aitken 10 June 6, in order of pages Aitken Lieutenant Colonel Sir Max Aitken. 08 April 5 M.P. Aitken lieutenant Corporal Sir Max Aitken 15 January 7 M.P. Author of forthcoming book Albrecht Albrecht Honours for Manchester 15 January 7 Regiment Allen Private Percy Allen ROLL OF HONOUR 09 December 4 Allen Private Percy Allen ROLL OF HONOUR 09 December 4 Allen Private George Harry Allen Machine Gun Corps. 16 September 6 Allen Private Percy Allen 2nd Manchesters 05 August 6 Allwood Private John W. Allwood Yorks and Lancaster 15 January 7 Regiment Anderson Private Harry Anderson 1/9th Manchester 12 February 6 Regiment Anderton Pt J Anderton ROLL OF HONOUR 14 October 4 Anderton Pt Joseph Anderton ROLL OF HONOUR 07 October 4 Andrew Driver