Effects of Landscape Elements on the Distribution of the Rare Bumblebee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beewalk Report 2020

BeeWalk Annual Report 2020 Richard Comont and Helen Dickinson BeeWalk Annual Report 2020 About BeeWalk BeeWalk is a standardised bumblebee-monitoring scheme active across Great Britain since 2008, and this report covers the period 2008–19. The scheme protocol involves volunteer BeeWalkers walking the same fixed route (a transect) at least once a month between March and October (inclusive). This covers the full flight period of the bumblebees, including emergence from overwintering and workers tailing off. Volunteers record the abundance of each bumblebee species seen in a 4 m x 4 m x 2 m ‘recording box’ in order to standardise between habitats and observers. It is run by Dr Richard Comont and Helen Dickinson of the Bumblebee Conservation Trust (BBCT). To contact the scheme organisers, please email [email protected]. Acknowledgements We are indebted to the volunteers and organisations past and present who have contributed data to the scheme or have helped recruit or train others in connection with it. Thanks must also go to all the individuals and organisations who allow or even actively promote access to their land for bumblebee recording. We would like to thank the financial contribution by the Redwing Trust, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, Garfield Weston Foundation and the many other organisations, charitable trusts and individuals who have supported the BeeWalk scheme in particular, and the Bumblebee Conservation Trust in general. In particular, the Biological Records Centre have provided website support, data storage and desk space free of charge. Finally, we would like to thank the photographers who have allowed their excellent images to be used as part of this BeeWalk Annual Report. -

Bumblebee in the UK

There are 24 species of bumblebee in the UK. This field guide contains illustrations and descriptions of the eight most common species. All illustrations 1.5x actual size. There has been a marked decline in the diversity and abundance of wild bees across Europe in recent decades. In the UK, two species of bumblebee have become extinct within the last 80 years, and seven species are listed in the Government’s Biodiversity Action Plan as priorities for conservation. This decline has been largely attributed to habitat destruction and fragmentation, as a result of Queen Worker Male urbanisation and the intensification of agricultural practices. Common The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security is conducting Tree bumblebee (Bombus hypnorum) research to encourage and support bumblebees in food Bumblebees growing areas on allotments and in gardens. Bees are of the United Kingdom Queens, workers and males all have a brown-ginger essential for food security, and are regarded as the most thorax, and a black abdomen with a white tail. This important insect pollinators worldwide. Of the 100 crop species that provide 90% of the world’s food, over 70 are recent arrival from France is now present across most pollinated by bees. of England and Wales, and is thought to be moving northwards. Size: queen 18mm, worker 14mm, male 16mm The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security (CAFS) is a joint initiative between Coventry University and Garden Organic, which brings together social and natural scientists whose collective research expertise in the fields of agriculture and food spans several decades. The Centre conducts critical, rigorous and relevant research which contributes to the development of agricultural and food production practices which are economically sound, socially just and promote long-term protection of natural Queen Worker Male resources. -

Bombus Terrestris) Colonies

veterinary sciences Article Replicative Deformed Wing Virus Found in the Head of Adults from Symptomatic Commercial Bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) Colonies Giovanni Cilia , Laura Zavatta, Rosa Ranalli, Antonio Nanetti * and Laura Bortolotti CREA Research Centre for Agriculture and Environment, Via di Saliceto 80, 40128 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (L.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The deformed wing virus (DWV) is one of the most common honey bee pathogens. The virus may also be detected in other insect species, including Bombus terrestris adults from wild and managed colonies. In this study, individuals of all stages, castes, and sexes were sampled from three commercial colonies exhibiting the presence of deformed workers and analysed for the presence of DWV. Adults (deformed individuals, gynes, workers, males) had their head exscinded from the rest of the body and the two parts were analysed separately by RT-PCR. Juvenile stages (pupae, larvae, and eggs) were analysed undissected. All individuals tested positive for replicative DWV, but deformed adults showed a higher number of copies compared to asymptomatic individuals. Moreover, they showed viral infection in their heads. Sequence analysis indicated that the obtained DWV amplicons belonged to a strain isolated in the United Kingdom. Further studies are needed to Citation: Cilia, G.; Zavatta, L.; characterize the specific DWV target organs in the bumblebees. The result of this study indicates the Ranalli, R.; Nanetti, A.; Bortolotti, L. evidence of DWV infection in B. -

Hoverflies: the Garden Mimics

Article Hoverflies: the garden mimics. Edmunds, Malcolm Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/1620/ Edmunds, Malcolm (2008) Hoverflies: the garden mimics. Biologist, 55 (4). pp. 202-207. ISSN 0006-3347 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk Hoverflies: the garden mimics Mimicry offers protection from predators by convincing them that their target is not a juicy morsel after all. it happens in our backgardens too and the hoverfly is an expert at it. Malcolm overflies are probably the best the mimic for the model and do not attack Edmunds known members of tbe insect or- it (Edmunds, 1974). Mimicry is far more Hder Diptera after houseflies, blue widespread in the tropics than in temperate bottles and mosquitoes, but unlike these lands, but we have some of the most superb insects they are almost universally liked examples of mimicry in Britain, among the by the general public. They are popular hoverflies. -

PETITION to LIST the VARIABLE CUCKOO BUMBLE BEE Bombus Variabilis (Cresson 1872) UNDER the ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT and CONCURRENTLY DESIGNATE CRITICAL HABITAT

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR PETITION TO LIST THE VARIABLE CUCKOO BUMBLE BEE Bombus variabilis (Cresson 1872) UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT AND CONCURRENTLY DESIGNATE CRITICAL HABITAT Variable Cuckoo Bumble Bee (top) male side (bottom) male face USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab Photo by Brook Goggins CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY April 27th, 2021 NOTICE OF PETITION Charles Wooley, Regional Director Deb Haaland, Secretary Region 3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Department of the Interior 5600 American Blvd. West, Suite 990 1849 C Street NW Bloomington, MN 55437-1458 Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] [email protected] Leopoldo Miranda, Regional Director Martha Williams, Principal Deputy Director Region 4 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1875 Century Blvd. NE 1849 C Street NW Atlanta, GA 30345 Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] [email protected] Gary Frazer, Assistant Director for Wendi Weber, Regional Director Endangered Species Region 5 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 300 Westgate Center Dr. 1840 C Street NW Hadley, MA 01035 Washington, D.C. 20240 [email protected] [email protected] Noreen Walsh, Regional Director Amy Leuders, Regional Director Region 6 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 650 P.O. Box 1306 Lakewood, CO 80228 Albuquerque, NM 87103-1306 [email protected] [email protected] ii Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b); Section 553(e) of the Administrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. -

Report for the Yellow Banded Bumble Bee (Bombus Terricola) Version 1.1

Species Status Assessment (SSA) Report for the Yellow Banded Bumble Bee (Bombus terricola) Version 1.1 Kent McFarland October 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Northeast Region Hadley, Massachusetts 1 Acknowledgements Gratitude and many thanks to the individuals who responded to our request for data and information on the yellow banded bumble bee, including: Nancy Adamson, U.S. Department of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS); Lynda Andrews, U.S. Forest Service (USFS); Sarah Backsen, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS); Charles Bartlett, University of Delaware; Janet Beardall, Environment Canada; Bruce Bennett, Environment Yukon, Yukon Conservation Data Centre; Andrea Benville, Saskatchewan Conservation Data Centre; Charlene Bessken USFWS; Lincoln Best, York University; Silas Bossert, Cornell University; Owen Boyle, Wisconsin DNR; Jodi Bush, USFWS; Ron Butler, University of Maine; Syd Cannings, Yukon Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada; Susan Carpenter, University of Wisconsin; Paul Castelli, USFWS; Sheila Colla, York University; Bruce Connery, National Park Service (NPS); Claudia Copley, Royal Museum British Columbia; Dave Cuthrell, Michigan Natural Features Inventory; Theresa Davidson, Mark Twain National Forest; Jason Davis, Delaware Division of Fish and Wildlife; Sam Droege, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS); Daniel Eklund, USFS; Elaine Evans, University of Minnesota; Mark Ferguson, Vermont Fish and Wildlife; Chris Friesen, Manitoba Conservation Data Centre; Lawrence Gall, -

Hymenoptera: Apidae)

BUMBLEBEES IN PRIME LANDSCAPES WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE ARAN ISLAND BUMBLEBEE (HYMENOPTERA: APIDAE) Aislinn Deenihan, B.Sc. (Env. Sci.) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, At the Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Limerick, Ireland. Supervisors: Prof. John Breen, Department of Life Sciences, University of Limerick. Dr. James Carolan, Department of Biology, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. Submitted to the University of Limerick May 2011 Abstract The Burren region (inclusive of the Aran Islands) in western Ireland is an example of a prime landscapes that hosts internationally rare bumblebee species, such as Bombus muscorum . For the conservation and survival of bumblebees it is important to know nest-site and spring forage plant preferences. Hence nest habitat choices of spring bumblebee queens in the Burren region was investigated by observing their nest-site seeking behaviour. In spring significant nest-site seeking behaviour associations were found for B. sylvarum , with preferences for calcareous grassland habitat and scrub- boundaries. The foraging preferences of bumblebee queens in spring were also recorded with B. sylvarum and B. ruderarius foraging most frequently from Vicia cracca and Lotus corniculatus , respectively. Significant interspecies foraging differences were found between bumblebee species recorded in this study. A melanic colour variety of B. muscorum is found in the Aran Islands, and similar varieties are known from several other islands off the British Isles. Considerable debate has taken place over the last 70 years concerning their taxonomic status. The phylogenetics and genetic differentiation of melanic colour morphs within B. muscorum were examined using DNA barcoding. On dried museum and recently caught alcohol-preserved specimens a novel technique involving a modification of the Qiagen DNeasy PBS DNA extraction protocol for insects was developed to extract DNA from the museum specimens. -

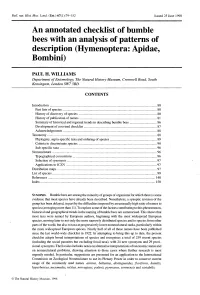

An Annotated Checklist of Bumble Bees with an Analysis of Patterns of Description (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Bombini)

Bull. nat. Hist. Mus. Lond. (Ent.) 67(1):79-152 Issued 25 June 1998 An annotated checklist of bumble bees with an analysis of patterns of description (Hymenoptera: Apidae, Bombini) PAUL H. WILLIAMS Department o f Entomology, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, South Kensington, London SW7 5BD CONTENTS Introduction......., ....................................... 80 Past lists of species........................................................................................................................ 80 History of discovery of species .................................................................................................... 80 History of publication of nam es...................................................................................................81 Summary of historical and regional trends in describing bumble b ees...................................86 Development of a revised checklist............................................................................................. 87 Acknowledgements............................. 88 Taxonomy............................................................................................................................................88 Phylogeny, supra-specific taxa and ordering of species............................................................89 Criteria to discriminate species............................................................................ 90 Sub-specific ta x a .......................................................................................................................... -

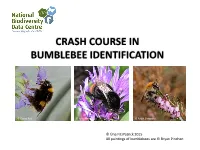

Crash Course in Bumblebee Identification

CRASH COURSE IN BUMBLEBEE IDENTIFICATION © Gypsy Ray © John Breen © Ralph Sheppard © Úna FitzPatrick 2015 All paintings of bumblebees are © Bryan Pinchen How many species are there in Ireland? 14 true bumblebees 20 6 cuckoo bumblebees Some bumblebee species are cleptoparasites or cuckoo species. Like the cuckoo bird, cuckoo bees lay their eggs in the nest of another bee species (their true bumblebee host) rather than bringing up their own offspring It is easiest to identify bumblebees when they are foraging on flowers. In this case it can also be possible to take a photograph for later identification. If you have a (butterfly) net it can be useful to catch bumblebees and have a closer look by briefly putting them in a plastic tube or clear ziploc sandwich bag. This will not harm the bumblebee & is recommended for beginners. Mountain Bumblebee photographed in a clear plastic tube Irish net suppliers: http://entomology.org.uk TRUE BUMBLEBEE IDENTIFICATION IN IRELAND: When identifying bumblebees the first step is to check the colour of the tail TRUE BUMBLEBEE IDENTIFICATION IN IRELAND: © Rodney Daunt 4* species have a white tail 5 species have a red tail © Rodney Daunt 1 species has a ginger tail 2 species have a blonde tail In the Data Centre’s Bumblebee guide, species are arranged by tail colour – if you see a bumblebee with a white tail you can fan out those 4 species in the swatch to assist with identification http://www.biodiversityireland.ie/home-page/shop/ TRUE BUMBLEBEE LIFECYCLE Forage and find a nest SPRING Queen emerges from Prepares a pollen loaf and a nectar hibernation in early spring pot and starts laying eggs fertilised with sperm stored from previous year Mated new queen forages AUTUMN to build up reserves before Female workers emerge hibernation. -

Conservation and Foraging Ecology of Bumble Bees In

Conservation and Foraging Ecology of Bumble Bees in Urban Environments Roselle E. Chapman A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of London. Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London & University College London. April 2004 1 UMI Number: U602843 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U602843 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The decline of British bumble bees has been attributed to the loss of their habitat through the intensification of agricultural practices. In the quest for information of use to bumble bee conservation the potential of our flower-rich cities has been overlooked. The overall aim of this study was to determine the status and foraging requirements of bumble bees in the urban environment provided by the city of London, U.K. My principal findings are as follows. Six common species and three rare species were identified. The greatest diversity of Bombus species was found in the east of London. Garden and wasteland habitats attracted the greatest abundance of workers and diversity of Bombus species. -

1 WNE 2019 18 Species Are Social Species. Remaining 6 Species Are

Bumblebees There are currently 24 species of bumblebee resident in Britain and 250 worldwide Bumblebees evolved in the Himalayas around 35 million years ago, and all species are quite closely related. The old English name for a Bumblebee is a Dumbledore just in case you ever wondered where JK Rowling got the name Another, the Short-haired bumblebee (Bombus subterraneus), is currently being reintroduced after going extinct in 1988. Britain also has two extinct bumblebee species: Cullum’s bumblebee (Bombus cullumanus) last recorded on the Berkshire Downs in 1941, and the Apple bumblebee (Bombus pomorum), a short-lived establishment on the south coast in the mid-1800s. They are wild, form short-lived social colonies (typically up to 3 months) and construct their own nests in cavities in hedgerows, under rocks, in disused mouse or birds’ nests, or in cavity walls. Bumblebees have the longest tongue of all UK bees reaching just over 2 cm at full stretch. The old English name for a Bumblebee is a Dumbledore just in case you ever wondered where JK Rowling got the name Seven species of bumblebee (the ‘Big 7’) are widespread across most of Britain. These are: . Red-tailed (Bombus lapidarius) . Early (Bombus pratorum) . Common carder (Bombus pascuorum) . White-tailed (Bombus lucorum) . Buff-tailed (Bombus terrestris) . Garden (Bombus hortorum) . Tree (Bombus hypnorum) The Heath bumblebee (Bombus jonellus) sometimes joins the group above, to form a ‘Big 8’, although it is absent from much of the English Midlands. There are 8 bumblebee species listed on at least one of the English, Welsh and Scottish conservation priority species lists. -

A Petition to List the Blue Calamintha

A Petition to list the Blue Calamintha Bee (Osmia calaminthae) as an Endangered, or Alternatively as a Threatened, Species Pursuant to the Endangered Species Act and for the Designation of Critical Habitat for this Species Blue Calamintha Bee (Osmia calaminthae) (Photo by Tim Lethbridge, used with permission, available at http://bugguide.net/node/view/394002/bgimage). Submitted to the United States Secretary of the Interior acting through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service February 5, 2015 By: Defenders of Wildlife1 535 16th Street, Suite 310 Denver, Colorado 80202 Phone: 720-943-0457 [email protected] [email protected] 1 Defenders of Wildlife would like to thank Olivia N. Kyle, a law student at the University of Denver, Sturm College of Law, for her substantial research and work preparing this Petition. I. INTRODUCTION Petitioner, Defenders of Wildlife (“Defenders”), is a national, non-profit, conservation organization dedicated to the protection of all native animals and plants in their natural communities. With more than one million members and activists, Defenders is a leading advocate for the protection of threatened and endangered species. Defenders’ 2013-2023 Strategic Plan identifies bees as one of several categories of key species whose conservation is a priority for our organization’s work.2 Through this Petition, Defenders formally requests the Secretary of the Interior, acting through the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (the “Service”), to list the Blue Calamintha Bee, Osmia calaminthae, (“Bee”) as an “endangered,” or alternatively as a “threatened,” species under the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”). 16 U.S.C. §§ 1531-44. Additionally, Defenders requests that the Service designate critical habitat for the Bee concurrently with the listing of the species.