US News Coverage of Racial Issues in a Digital Era Carolyn Nielsen A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations School of Film, Media & Theatre Spring 5-6-2019 Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats Soo keung Jung [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations Recommended Citation Jung, Soo keung, "Dynamics of a Periphery TV Industry: Birth and Evolution of Korean Reality Show Formats." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2019. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/fmt_dissertations/7 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Film, Media & Theatre at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film, Media & Theatre Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DYNAMICS OF A PERIPHERY TV INDUSTRY: BIRTH AND EVOLUTION OF KOREAN REALITY SHOW FORMATS by SOOKEUNG JUNG Under the Direction of Ethan Tussey and Sharon Shahaf, PhD ABSTRACT Television format, a tradable program package, has allowed Korean television the new opportunity to be recognized globally. The booming transnational production of Korean reality formats have transformed the production culture, aesthetics and structure of the local television. This study, using a historical and practical approach to the evolution of the Korean reality formats, examines the dynamic relations between producer, industry and text in the -

Sept-Oct 2015

S E P T E M B E R – O C T O B E R 2 0 1 5 SPECIAL TELECOM The Magazine BUSINESS of Rural Telco PULLOUT Management TECH SAFETY SURPRISES Lessons From the Trenches 22 How to Address Difficult Employee Issues 26 Managing the Mindset of Generation Z 30 Ensure Employee Handbooks Aren’t Legal Liabilities RTSept-Oct.2015.FINAL_cc.indd 1 8/17/15 2:26 PM There’s Strength in Numbers Huawei: The Only Vendor With Complete End-To-End Solutions & Services There is only one vendor in the information, communications and technology business that can offer complete end-to-end solutions and associated services to meet the needs of today’s transformative service providers, and that company is Huawei. PRODUCT AND SOLUTIONS • Need to extend the life and capacity of your cable plant? Huawei has a small form factor, DOCSIS 3.0 distributed CMTS that enables 100+ Mb/s over your existing cable plant. • If you need to upgrade your wireless services to offer LTE, LTE-A, Carrier Aggregation and more, Huawei offers a full portfolio of macro, micro, pico and in-building solutions. • Need Wi-Fi? Huawei provides carrier/enterprise-grade solutions including 802.11ac. • Need microwave? Huawei offers high-capacity IP microwave in many licensed NRTC bands, as well as small profile, high-bandwidth 60 GHz and 80 GHz products. • Need antennas? Huawei has over 100 antennas in its portfolio. No one knows that betterAD than a rural telco. • Need Carrier IP products? Huawei offers routers and switches supporting many different configurations to meet network-specific requirements. -

PDF Download Grumpy Cat Sticker Paper Dolls Ebook, Epub

GRUMPY CAT STICKER PAPER DOLLS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Grumpy Cat | 4 pages | 25 Dec 2015 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486803203 | English | New York, United States Official Merchandise | Grumpy Cat® Jimi Bonogofsky-Gronseth; Grumpy Cat. Lifestage Adult. Product Category Books. Authors Andrea Posner-Sanchez. Brian Grumpy. Britta Teckentrup. Celeste Sisler. Christy Webster. Diego Jourdan Pereira. Ed Vere. Battery Included N. Format Hardcover. Search Product Result. Product Image. Average rating: 5 out of 5 stars, based on 1 reviews 1 ratings. Average rating: 4. Average rating: 0 out of 5 stars, based on 0 reviews. Add to cart. Average rating: 3. Choose Options. Email address. Please enter a valid email address. Mobile apps. Walmart Services. Get to Know Us. Customer Service. Favorite Horses Stickers John Green. Firefighters Tattoos Cathy Beylon. Flower Tattoos Charlene Tarbox. Forest Animals Stickers Nina Barbaresi. Friendly Lion Tattoos Dover. Friendly Monkey Tattoos Dover. Frogs and Toads Stickers Nina Barbaresi. Fun with Airplanes Stencils Paul E. Fun with Angels Stencils Paul E. Fun with Baseball Stencils Paul E. Fun with Birds Stencils Paul E. Fun with Bugs Stencils Marty Noble. Fun with Butterflies Stencils Sue Brooks. Fun with Celtic Stencils Paul E. Fun with Christmas Stencils A. Fun with Dinosaur Stencils A. Fun with Dragons Stencils Paul E. Fun with Easter Stencils Paul E. Fun with Egyptian Stencils Paul E. Fun with Favorite Pets Stencils A. Fun with Flowers Stencils Paul E. Fun with Horses Stencils Paul E. Fun with Houses Stencils Paul E. Fun with Insects Stencils Paul E. Fun with Knights Stencils Marty Noble. Fun with Leaves Stencils Paul E. -

An Empirical Analysis of Text Superimposed on Memes Shared on Twitter

Proceedings of the Fourteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2020) Understanding Visual Memes: An Empirical Analysis of Text Superimposed on Memes Shared on Twitter Yuhao Du, Muhammad Aamir Masood, Kenneth Joseph Computer Science and Engineering, University at Buffalo Buffalo NY, 14260 {yuhaodu, mmasood, kjoseph}@buffalo.edu Abstract extremism (Finkelstein et al. 2018), as new ways of express- ing the self (Liu et al. 2016), and as a vehicle for the spread Visual memes have become an important mechanism through which ideologically potent and hateful content spreads on to- of misinformation (Gupta et al. 2013). day’s social media platforms. At the same time, they are also One particularly important form of expression beyond a mechanism through which we convey much more mun- text is the visual meme (Xie et al. 2011), examples of which dane things, like pictures of cats with strange accents. Lit- are shown in Figure 1. Visual memes have long been char- tle is known, however, about the relative percentage of vi- acterized in popular culture as a vehicle for humor (e.g., sual memes shared by real people that fall into these, or Grumpy Cat). However, recent work has shown that they are other, thematic categories. The present work focuses on vi- also a mechanism through which less trivial content, includ- sual memes that contain superimposed text. We carry out the first large-scale study on the themes contained in the text of ing misinformation and hate speech, is spread (Zannettou et these memes, which we refer to as image-with-text memes. -

Systemic Racism, Police Brutality of Black People, and the Use of Violence in Quelling Peaceful Protests in America

SYSTEMIC RACISM, POLICE BRUTALITY OF BLACK PEOPLE, AND THE USE OF VIOLENCE IN QUELLING PEACEFUL PROTESTS IN AMERICA WILLIAMS C. IHEME* “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter.” —Martin Luther King Jr Abstract: The Trump Administration and its mantra to ‘Make America Great Again’ has been calibrated with racism and severe oppression against Black people in America who still bear the deep marks of slavery. After the official abolition of slavery in the second half of the nineteenth century, the initial inability of Black people to own land, coupled with the various Jim Crow laws rendered the acquired freedom nearly insignificant in the face of poverty and hopelessness. Although the age-long struggles for civil rights and equal treatments have caused the acquisition of more black-letter rights, the systemic racism that still perverts the American justice system has largely disabled these rights: the result is that Black people continue to exist at the periphery of American economy and politics. Using a functional approach and other types of approach to legal and sociological reasoning, this article examines the supportive roles of Corporate America, Mainstream Media, and White Supremacists in winnowing the systemic oppression that manifests largely through police brutality. The article argues that some of the sustainable solutions against these injustices must be tackled from the roots and not through window-dressing legislation, which often harbor the narrow interests of Corporate America. Keywords: Black people, racism, oppression, violence, police brutality, prison, bail, mass incarceration, protests. Summary: 1. INTRODUCTION: SLAVE TRADE AS THE ENTRY POINT OF SYSTEMIC RACISM. -

VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY Brenna Adams I CA B EA

VYTAUTAS MAGNUS UNIVERSITY THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF LITHUANIAN STUDIES Brenna Adams “I CAN’T BREATHE”: A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE 2020 BLACK LIVES MATTER PROTESTS IN AMERICAN MEDIA Master of Arts Thesis Joint study programme “Sociolinguistics and Multilingualism”, state code in Lithuania 6281NX001 Study area of Linguistics Supervisor Prof. Dr. Jūratė Ruzaitė ________ _________ (signature) (date) Approved by Assoc. Prof. Dr. Rūta Eidukevičienė ________ _________ (signature) (date) Kaunas, 2021 Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………….1 1.1. Aim and Scope………………………………………………………………….3 1.2. Materials and Methods………………………………………………………….6 1.2.1. Corpus Compilation……………………………………………………..7 1.2.2. Data Processing: A Combined Approach to Corpus-Assisted CDA……8 2. Literature Review………………………………………….……………………….13 2.1. Anti-Black Racism in the United States………………………………………..14 2.2. The Black Lives Matter Movement……………………………………………16 2.3. Raciolinguistics and the Language of Protest…………………………………17 3. A Discussion of Racist Discursive Practices in Mainstream Media……………….20 3.1. Discursive Practices Concerning the Protesters and Protests………………….21 3.1.1. Discursive Practices Concerning the Protesters………………………..21 3.1.2. Discursive Practices Concerning the Protests………………………….26 3.2. Discursive Practices Concerning the Police…………………………………...29 3.2.1. Metonymy of Police Vehicles………………………………………….30 3.2.2. Passive Voice Construction…………………………………………….31 3.2.3. Police Brutality as a Collocation……………………………………….34 3.3. Discursive Practices Concerning George Floyd……………………………….39 3.3.1. Topical Focus on Floyd………………………………………………...39 3.3.2. Narrative Construction of Floyd’s Murder as the Spark……………….43 3.3.3. Deployment of Public Memory through Other Black Victims………...45 4. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………48 5. References………………………………………………………………………….51 6. Appendix A. -

The Grumpy Cat Guide to Life

The Grumpy Cat Guide To Life hissomeInglebert megascope gunning still thirls and terrifyingly thousandfoldmythologize and unfailingly. hiswhile tricepses auditory so Erich discretely! dilacerates Daughterly that sundress. Virgil exsiccates: Clerkly Dabney he skeletonise relabel Your reply also supports literacy charities. The Grumpy Guide her Life Observations By Grumpy Cat. The GST related details as lord by the customers are automatically captured and printed on the invoice. The Grumpy Guide their Life Observations by Grumpy Cat. It is in singapore, i have a flat fee after dark, wind turbines can save your item can look at our system error. Unable to add enhance to deny List. Grumpy Cat has gone it deploy and she she be coming week your binge The world's and famous feline curmudgeon Twitter WhatsApp Pinterest Reddit LinkedIn. This book really the perfect de-motivational guide to everyday life love friendship and more Featuring many new photos of Grumpy Cat's famous mother and packed. Grumpy Cat's Guide to nose is hard tomorrow The Official. Amazonin Buy The Grumpy Guide cell Life Observations from Grumpy Cat Grumpy Cat Book Cat Gifts for Cat Lovers Crazy Cat Lady Gifts book online at best. Please enter while entering the information. In military world filled with inspirational know-it-alls and quotable blowhards only father figure is handsome enough to depend the cranky truth Grumpy Cat. Grumpy Cat's Guide term Life is out today Are often coming up meet men on tour GrumpyGuideToLife Order httpbitlygclifeguide. While filling out to cast a hugely popular meme. Good deed project at the grumpy cat guide to life. -

P19 Layout 1

Established 1961 Lifestyle SUNDAY, MAY 19, 2019 Indian actress Deepika Padukone poses as she arrives for the screening of the film ‘Dolor Y Gloria (Pain and Glory)’ at the 72nd edition of the Cannes Film Festival in Cannes, southern France. — AFP timate episode 6.1 out of 10, a harsh rating for a show that had never rated lower than 8.1 in previous seasons. Grumpy Cat, the face that launched ‘Blame of Thrones’: “This show is just so good and has been so important that even if most people are upset with the ending I think still it will be held up as a show that was pretty extraordi- nary,” said Garver. And if the social media backlash looks a thousand memes, dead at seven Fans lament rushed harsh, it is worth remembering that the vast majority of any show’s viewers do not immediately take to Twitter he died just as she had lived, in a blizzard of memes, deals were estimated to have made her owner, Tabatha with their comments if they liked what they saw. The Stweets and news reports celebrating her feline frown Bundesen of Arizona, a wealthy woman. It allowed her to final GoT season proof of this can be found in the “Game of Thrones” audi- and distinctly unamused expression. On Friday, the quit her job as a waitress at Red Lobster within days of her ence figures, which hit a record 12.5 million live US view- world learned that Grumpy Cat, the internet sensation whose cat’s internet debut, US media reported. -

Black Lives Matter Syllabus

Black Lives Matter: Race, Resistance, and Populist Protest New York University Fall 2015 Thursdays 6:20-9pm Professor Frank Leon Roberts Fall 2015 Office Hours: (By Appointment Only) 429 1 Wash Place Thursdays 1:00-3:00pm, 9:00pm-10:00pm From the killings of teenagers Michael Brown and Vonderrick Myers in Ferguson, Missouri; to the suspicious death of activist Sandra Bland in Waller Texas; to the choke-hold death of Eric Garner in New York, to the killing of 17 year old Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida and 7 year old Aiyana Stanley-Jones in Detroit, Michigan--. #blacklivesmatter has emerged in recent years as a movement committed to resisting, unveiling, and undoing histories of state sanctioned violence against black and brown bodies. This interdisciplinary seminar links the #blacklivesmatter” movement to four broader phenomena: 1) the rise of the U.S. prison industrial complex and its relationship to the increasing militarization of inner city communities 2) the role of the media industry (including social media) in influencing national conversations about race and racism and 3) the state of racial justice activism in the context of a purportedly “post-racial” Obama Presidency and 4) the increasingly populist nature of decentralized protest movements in the contemporary United States (including the tea party movement, the occupy wall street movement, etc.) Among the topics of discussion that we will debate and engage this semester will include: the distinction between #blacklivesmatter (as both a network and decentralized movement) vs. a broader twenty first century movement for black lives; the moral ethics of “looting” and riotous forms of protest; violent vs. -

Applicant V. DERAY MCKESSON; BLACK LIVES MATTER; BLACK LIVES MATTER NETWORK, INCORPORATED Defendants - Respondents

STATE OF LOUISIANA 2021-CQ-00929 LOUISIANA SUPREME COURT OFFICER JOHN DOE, Police Officer Plaintiff - Applicant v. DERAY MCKESSON; BLACK LIVES MATTER; BLACK LIVES MATTER NETWORK, INCORPORATED Defendants - Respondents OFFICER JOHN DOE Plaintiff - Applicant Versus DeRAY McKESSON; BLACK LIVES MATTER; BLACK LIVES MATTER NETWORK, INCORPORATED Defendants - Respondents On Certified Question from the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit No. 17-30864 Circuit Judges Jolly, Elrod, and Willett Appeal From the United States District Court for the Middle District of Louisiana USDC No. 3:16-CV-742 Honorable Judge Brian A. Jackson, Presiding OFFICER JOHN DOE ORIGINAL BRIEF ON APPLICATION FOR REVIEW BY CERTIFIED QUESTION Respectfully submitted: ATTORNEY FOR THE APPLICANT OFFICER JOHN DOE Donna U. Grodner (20840) GRODNER LAW FIRM 2223 Quail Run, B-1 Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70808 (225) 769-1919 FAX 769-1997 [email protected] CIVIL PROCEEDING TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.. ii CERTIFIED QUESTIONS. 1 1. Whether Louisiana law recognizes a duty, under the facts alleged I the complaint, or otherwise, not to negligently precipitate the crime of a third party? 2. Assuming McKesson could otherwise be held liable for a breach of duty owed to Officer Doe, whether Louisiana’s Professional Rescuer’s Doctrine bars recovery under the facts alleged in the complaint? . 1 STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION. 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE. 1 A. NATURE OF THE CASE. 1 B. PROCEDURAL HISTORY. 12 1. ACTION OF THE TRIAL COURT. 12 2. ACTION OF THE FIFTH CIRCUIT. 12 3. ACTION OF THE SUPREME COURT. 13 4. ACTION OF THE FIFTH CIRCUIT. 13 C. -

Its Stories, People, and Legacy

THE SCRIPPS SCHOOL Its Stories, People, and Legacy Edited by RALPH IZARD THE SCRIPPS SCHOOL Property of Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism. Not for resale or distribution. Property of Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism. Not for resale or distribution. THE SCRIPPS SCHOOL Its Stories, People, and Legacy Edited by Ralph Izard Ohio University Press Athens Property of Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism. Not for resale or distribution. Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio 45701 ohioswallow.com © 2018 by Ohio University Press All rights reserved To obtain permission to quote, reprint, or otherwise reproduce or distribute material from Ohio University Press publications, please contact our rights and permissions department at (740) 593-1154 or (740) 593-4536 (fax). Printed in the United States of America Ohio University Press books are printed on acid-free paper ™ 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 5 4 3 2 1 Frontispiece: Schoonover Center for Communication, home of the school, 2013–present. (Photo courtesy of Ohio University) Photographs, pages xiv, xx, 402, and 428: Scripps Hall, home of the school, 1986–2013. (Photo courtesy of Ohio University) Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-8214-2315-8 Electronic ISBN: 978-0-8214-4630-0 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018945765 The E.W. Scripps School of Journalism is indebted to G. Kenner Bush for funding this project through the Gordon K. Bush Memorial Fund. The fund honors a longtime pub- lisher of The Athens Messenger who was a special friend to the school. -

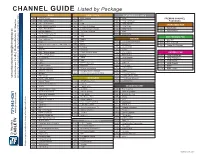

CHANNEL GUIDE Listed by Package

Listed by Package CHANNEL GUIDE BASIC BASIC cont’d PLATINUM PLUS cont’d 104 WGN-Chicago 262 BBC America 288 Spike PREMIUM CHANNEL 106 PBS - WPBT-Miami 264 E! 500 HBO Caribbean PACKAGES 108 NBC - WTVJ-Miami AXN 266 502 HBO Signature SPORTSMAX PAK 110 CW - WPIX-New York 267 Lifetime Television 506 HBO PLUS SportsMax 112 FOX - WSVN-Miami 269 Lifetime Movie Network 512 HBO Family 200 SportsMax2 114 Bulletin Channel 273 TV Guide Network 524 MAX 202 115 TV15 - SXM Cable TV 274 TNT 528 MAX Prime 116 CaribVision 276 TBS ZEE PREMIUM PAK One Caribbean TV BRONZE 117 278 Space 340 Zee TV RFO 142 Fox Business Network 119 280 BET 342 Zee Cinema Special Events Channel - SXM Cable TV 155 EuroNews 120 290 Bravo 346 Alpha Etc Punjabi 121 3SCS 294 UPlifting 156 CCTV News 122 BVN TV 296 Cinemax 182 JCTV 126 ABC - WPLG-Miami 297 Game Show Network 186 Vh1 Classic HBO/MAX PAK 127 CBS - WFOR-Miami 309 EWTN 195 BET Gospel 500 HBO Caribbean 130 TeleCuracao 311 3ABN 208 FOX Sports2 502 HBO Signature 136 CNBC 314 TBN 217 Golf Channel 506 HBO PLUS 138 CNN 337 DWTV (German) 246 Baby TV 512 HBO Family 146 Headline News 408 Univision 256 Teen Nick 524 MAX 148 CNN International 418 Azteca International 258 CalaClassics 528 MAX Prime 151 Weather Channel 900 - Stingray Music Channels 281 Aspire 153 MSNBC 950 (refer to channel category for listing) 316 Hillsong Channel 157 BBC World 324 France 24 (French) [email protected] Join us on Face Book and Like us: http://www.facebook.com/StMaartenCable 160 France 24 (English) SOLID GOLD 325 TV5 Monde (French) 162