W O R K I N G P a P E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arquitecto Y Humanista

50 Nuestros maestros Marcial Gutiérrez Camarena: Arquitecto y humanista Cecilia Gutiérrez Arriola Académica del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas de la UNAM igura predominante en el ámbito de la docencia de la arqui- el periodo virreinal. Su infancia transcurre en la ciudad de Tepic, tectura y la vida académica de la Escuela Nacional de Ar- adonde se muda la familia en busca de una mejor economía, en quitectura de los años cuarenta, a Marcial Gutiérrez tiempos en que el porfiriato agonizaba y estallaba la lucha arma- Camarena aún se le recuerda porque fue un hombre comprome- da. En noviembre de 1919, junto con su hermano Alberto, se tras- tido con su profesión y un universitario entregado a la transmi- ladó a la Ciudad de México, emprendiendo la dificil aventura de sión del conocimiento. dejar la tierra natal y trabajar para poder estudiar. Hizo el ba- Participe de una brillante y privilegiada generación que se chillerato en el Colegio Francés Morelos, de los Maristas, y en formó bajo la égida del padre del Movimiento Moderno y del 1923, ingresó a la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes, en la vieja gran maestro que fue José Villagrán García, grupo que trascen- Academia de San Carlos, que ya estaba incorporada a la Uni- dió no sólo por el sino por la huella que marcó con sus propues- versidad Nacional, para estudiar la carrera de arquitectura, tas funcionalistas en la arquitectura mexicana. cuando la ciudad de México empezaba a vivir grandes momen- Nació en San Blas, Nayarit, en febrero de1898, cuando su pa- tos en la educación y la cultura, propiciados por el ministro Jo- dre trabajaba para la Casa de comercio Lanzagorta y fungía como sé Vasconcelos. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Abulfeda crater chain (Moon), 97 Aphrodite Terra (Venus), 142, 143, 144, 145, 146 Acheron Fossae (Mars), 165 Apohele asteroids, 353–354 Achilles asteroids, 351 Apollinaris Patera (Mars), 168 achondrite meteorites, 360 Apollo asteroids, 346, 353, 354, 361, 371 Acidalia Planitia (Mars), 164 Apollo program, 86, 96, 97, 101, 102, 108–109, 110, 361 Adams, John Couch, 298 Apollo 8, 96 Adonis, 371 Apollo 11, 94, 110 Adrastea, 238, 241 Apollo 12, 96, 110 Aegaeon, 263 Apollo 14, 93, 110 Africa, 63, 73, 143 Apollo 15, 100, 103, 104, 110 Akatsuki spacecraft (see Venus Climate Orbiter) Apollo 16, 59, 96, 102, 103, 110 Akna Montes (Venus), 142 Apollo 17, 95, 99, 100, 102, 103, 110 Alabama, 62 Apollodorus crater (Mercury), 127 Alba Patera (Mars), 167 Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP), 110 Aldrin, Edwin (Buzz), 94 Apophis, 354, 355 Alexandria, 69 Appalachian mountains (Earth), 74, 270 Alfvén, Hannes, 35 Aqua, 56 Alfvén waves, 35–36, 43, 49 Arabia Terra (Mars), 177, 191, 200 Algeria, 358 arachnoids (see Venus) ALH 84001, 201, 204–205 Archimedes crater (Moon), 93, 106 Allan Hills, 109, 201 Arctic, 62, 67, 84, 186, 229 Allende meteorite, 359, 360 Arden Corona (Miranda), 291 Allen Telescope Array, 409 Arecibo Observatory, 114, 144, 341, 379, 380, 408, 409 Alpha Regio (Venus), 144, 148, 149 Ares Vallis (Mars), 179, 180, 199 Alphonsus crater (Moon), 99, 102 Argentina, 408 Alps (Moon), 93 Argyre Basin (Mars), 161, 162, 163, 166, 186 Amalthea, 236–237, 238, 239, 241 Ariadaeus Rille (Moon), 100, 102 Amazonis Planitia (Mars), 161 COPYRIGHTED -

Modernism Without Modernity: the Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Management Papers Wharton Faculty Research 6-2004 Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Mauro F. Guillen University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, and the Management Sciences and Quantitative Methods Commons Recommended Citation Guillen, M. F. (2004). Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940. Latin American Research Review, 39 (2), 6-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/lar.2004.0032 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/mgmt_papers/279 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modernism Without Modernity: The Rise of Modernist Architecture in Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina, 1890-1940 Abstract : Why did machine-age modernist architecture diffuse to Latin America so quickly after its rise in Continental Europe during the 1910s and 1920s? Why was it a more successful movement in relatively backward Brazil and Mexico than in more affluent and industrialized Argentina? After reviewing the historical development of architectural modernism in these three countries, several explanations are tested against the comparative evidence. Standards of living, industrialization, sociopolitical upheaval, and the absence of working-class consumerism are found to be limited as explanations. As in Europe, Modernism -

From Resort to Gallery: Nation Building in Clara Porset's

Dearq ISSN: 2215-969X [email protected] Universidad de Los Andes Colombia From Resort to Gallery: Nation Building in Clara Porset’s Interior Spaces* Vivanco, Sandra I. From Resort to Gallery: Nation Building in Clara Porset’s Interior Spaces* Dearq, núm. 23, 2018 Universidad de Los Andes, Colombia Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=341667565005 DOI: https://doi.org/10.18389/dearq23.2018.04 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Investigación Temática From Resort to Gallery: Nation Building in Clara Porset’s Interior Spaces* Del Resort a la Galería: la construcción de nación en los espacios interiores de Clara Porset De Resort a Galeria: Construção Nacional nos Espaços Interiores de Clara Porset Sandra I. Vivanco [email protected] California College of the Arts, Estados Unidos Abstract: Modern design in Latin America exists between technological utopia and artisanal memory. Oen anachronistic, this tension has historically sponsored the use of unusual materials and unorthodox construction methods. is article critically analyzes key interior spaces designed by Cuban born Clara Porset in mid-century Mexico that Dearq, núm. 23, 2018 interrogate traditional interior and exterior notions and question boundaries between public and private. By exploring both her posh and serene collective interior spaces Universidad de Los Andes, Colombia within early Mexican resort hotels and her well-considered minimal furnishings for Recepción: 19 Febrero 2018 affordable housing units, we confirm that both kinds of projects call into question issues Aprobación: 21 Mayo 2018 of class, gender, and nation building. -

TORRE REFORMA: Um Arranha-Céu Regionalista

XIII Semana de Extensão, Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação - SEPesq Centro Universitário Ritter dos Reis TORRE REFORMA: Um Arranha-Céu Regionalista Luís Henrique Bueno Villanova Mestrando no PPAU UniRitter/Mackenzie UniRitter/Mackenzie [email protected] Maria Paula Recena (orientadora) Drª Arquitetura (UFRGS 2013); Me Poéticas Visuais (UFRGS 2005) UniRitter/Mackenzie [email protected] Resumo: Tendo como base o capítulo, Três Conceitos – Torre Reforma, da dissertação em desenvolvimento sobre arranha-céus no século XXI, este artigo traz como objetivo entender como a cultura local pode estar relacionada à uma edificação em altura. Como premissa, o estudo segue publicações resultantes das conferências do Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) que discutem o futuro dos arranha-céus e como estes tiram proveito das características culturais do local de inserção, demonstrado no estudo de caso da Torre Reforma na Cidade do México. Assim explora-se também a necessidade de um entendimento da ligação do movimento moderno com uma corrente de arquitetura regionalista no México para melhor compreender como esse povo associa cultura na arquitetura de edificações. 1 Introdução A cultura de um povo pode ser traduzida para um arranha-céu? Segundo o Diretor Executivo do Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH), Antony Wood (2014), o aspecto cultural é o menos tangível de atingir em um projeto de arranha-céu, pois a cultura de uma cidade está associada aos padrões de vida, manifestando-se nos costumes, atividades e expressões da população. Para Roberto Goodwin (2015), o mais desafiador é definir um sentido de expressar o contexto cultural através do design. Fazer arquitetura onde se sabe que a cultura permite abordar e desafiar as crenças, comportamento e estética, requer um processo interpretativo e subjetivo com relação aos sensos pessoais de valores e riqueza de um projeto. -

De Porfirio Díaz. La Otra Sección Del Terreno Que Ocupó Aquella Mansión Se Empleó Para Continuar La Calle De Edison Hasta Rosales

SECRETARÍA DE CULTURA DIRECCIÓN GENERAL DE PATRIMONIO HISTÓRICO, ARTÍSTICO Y CULTURAL de Porfirio Díaz. La otra sección del terreno que ocupó aquella mansión se empleó para continuar la calle de Edison hasta Rosales. En 1936 se inició la construcción del Hotel Reforma, de Mario Pani, en la esquina con la calle París. Contaba con 545 habitaciones cada una con su baño. Considerado como el primer hotel moderno en la ciudad, contaba con roof garden, el bar Tap Room, el restaurante París, cafetería, el salón Champagne, una tienda llamada Chilpa Men’s Shop, peluquería, florería, farmacia y bar. En suma, todo lo necesario para ser un hotel de primera categoría.78 Durante el gobierno del general Lázaro Cárdenas, Lomas de Chapultepec crecía y se poblaba. Como parte del desarrollo que se experimentaba en la zona, entre 1937 y 1938, se fraccionó otra parte de la Hacienda de los Morales para crear Polanco, tal como se consigna en la placa colocada en la base del obelisco dedicado a Simón Bolívar. El obelisco marca el acceso original al fraccionamiento y con el paso del tiempo se ha convertido en uno de los símbolos de la colonia. Fue colocado en la confluencia de Paseo de la Reforma con las calles Julio Verne y Campos Elíseos. La obra fue proyectada por el arquitecto Enrique Aragón Echegaray —quien fuera autor de otros hitos como el Monumento a Álvaro Obregón y el Monumento a los Niños Héroes—, y del escultor Enrique Guerra, egresado de la Academia de San Carlos.79 La placa del monumento también menciona que el proyecto de lotificación fue diseñado por don José G. -

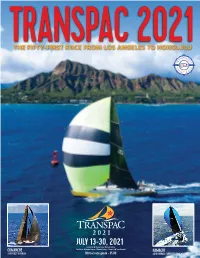

2021 Transpacific Yacht Race Event Program

TRANSPACTHE FIFTY-FIRST RACE FROM LOS ANGELES 2021 TO HONOLULU 2 0 21 JULY 13-30, 2021 Comanche: © Sharon Green / Ultimate Sailing COMANCHE Taxi Dancer: © Ronnie Simpson / Ultimate Sailing • Hamachi: © Team Hamachi HAMACHI 2019 FIRST TO FINISH Official race guide - $5.00 2019 OVERALL CORRECTED TIME WINNER P: 808.845.6465 [email protected] F: 808.841.6610 OFFICIAL HANDBOOK OF THE 51ST TRANSPACIFIC YACHT RACE The Transpac 2021 Official Race Handbook is published for the Honolulu Committee of the Transpacific Yacht Club by Roth Communications, 2040 Alewa Drive, Honolulu, HI 96817 USA (808) 595-4124 [email protected] Publisher .............................................Michael J. Roth Roth Communications Editor .............................................. Ray Pendleton, Kim Ickler Contributing Writers .................... Dobbs Davis, Stan Honey, Ray Pendleton Contributing Photographers ...... Sharon Green/ultimatesailingcom, Ronnie Simpson/ultimatesailing.com, Todd Rasmussen, Betsy Crowfoot Senescu/ultimatesailing.com, Walter Cooper/ ultimatesailing.com, Lauren Easley - Leialoha Creative, Joyce Riley, Geri Conser, Emma Deardorff, Rachel Rosales, Phil Uhl, David Livingston, Pam Davis, Brian Farr Designer ........................................ Leslie Johnson Design On the Cover: CONTENTS Taxi Dancer R/P 70 Yabsley/Compton 2019 1st Div. 2 Sleds ET: 8:06:43:22 CT: 08:23:09:26 Schedule of Events . 3 Photo: Ronnie Simpson / ultimatesailing.com Welcome from the Governor of Hawaii . 8 Inset left: Welcome from the Mayor of Honolulu . 9 Comanche Verdier/VPLP 100 Jim Cooney & Samantha Grant Welcome from the Mayor of Long Beach . 9 2019 Barndoor Winner - First to Finish Overall: ET: 5:11:14:05 Welcome from the Transpacific Yacht Club Commodore . 10 Photo: Sharon Green / ultimatesailingcom Welcome from the Honolulu Committee Chair . 10 Inset right: Welcome from the Sponsoring Yacht Clubs . -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Title: the Avant-Garde in the Architecture and Visual Arts of Post

1 Title: The avant-garde in the architecture and visual arts of Post-Revolutionary Mexico Author: Fernando N. Winfield Architecture_media_politics_society. vol. 1, no.3. November 2012 Mexico City / Portrait of an Architect with the City as Background. Painting by Juan O´Gorman (1949). Museum of Modern Art, Mexico. Commenting on an exhibition of contemporary Mexican architecture in Rome in 1957, the polemic and highly influential Italian architectural critic and historian, Bruno Zevi, ridiculed Mexican modernism for combining Pre-Columbian motifs with modern architecture. He referred to it as ‘Mexican Grotesque.’1 Inherent in Zevi’s comments were an attitude towards modern architecture that defined it in primarily material terms; its principle role being one of “spatial and programmatic function.” Despite the weight of this Modernist tendency in the architectural circles of Post-Revolutionary Mexico, we suggest in this paper that Mexican modernism cannot be reduced to such “material” definitions. In the highly charged political context of Mexico in the first half of the twentieth century, modern architecture was perhaps above all else, a tool for propaganda. ARCHITECTURE_MEDIA_POLITICS_SOCIETY Vol. 1, no.3. November 2012 1 2 In this political atmosphere it was undesirable, indeed it was seen as impossible, to separate art, architecture and politics in a way that would be a direct reflection of Modern architecture’s European manifestations. Form was to follow function, but that function was to be communicative as well as spatial and programmatic. One consequence of this “political communicative function” in Mexico was the combination of the “mural tradition” with contemporary architectural design; what Zevi defined as “Mexican Grotesque.” In this paper, we will examine the political context of Post-Revolutionary Mexico and discuss what may be defined as its most iconic building; the Central Library at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. -

DMAAC – February 1973

LUNAR TOPOGRAPHIC ORTHOPHOTOMAP (LTO) AND LUNAR ORTHOPHOTMAP (LO) SERIES (Published by DMATC) Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Scale: 1:250,000 Projection: Transverse Mercator Sheet Size: 25.5”x 26.5” The Lunar Topographic Orthophotmaps and Lunar Orthophotomaps Series are the first comprehensive and continuous mapping to be accomplished from Apollo Mission 15-17 mapping photographs. This series is also the first major effort to apply recent advances in orthophotography to lunar mapping. Presently developed maps of this series were designed to support initial lunar scientific investigations primarily employing results of Apollo Mission 15-17 data. Individual maps of this series cover 4 degrees of lunar latitude and 5 degrees of lunar longitude consisting of 1/16 of the area of a 1:1,000,000 scale Lunar Astronautical Chart (LAC) (Section 4.2.1). Their apha-numeric identification (example – LTO38B1) consists of the designator LTO for topographic orthophoto editions or LO for orthophoto editions followed by the LAC number in which they fall, followed by an A, B, C or D designator defining the pertinent LAC quadrant and a 1, 2, 3, or 4 designator defining the specific sub-quadrant actually covered. The following designation (250) identifies the sheets as being at 1:250,000 scale. The LTO editions display 100-meter contours, 50-meter supplemental contours and spot elevations in a red overprint to the base, which is lithographed in black and white. LO editions are identical except that all relief information is omitted and selenographic graticule is restricted to border ticks, presenting an umencumbered view of lunar features imaged by the photographic base. -

The Casa Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2001 Towards Establishing a Process for Preserving Historic Landscapes in Mexico: The aC sa Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico Marcela De Obaldia Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation De Obaldia, Marcela, "Towards Establishing a Process for Preserving Historic Landscapes in Mexico: The asC a Cristo Gardens in Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico" (2001). LSU Master's Theses. 2239. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2239 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TOWARDS ESTABLISHING A PROCESS FOR PRESERVING HISTORIC LANDSCAPES IN MEXICO: THE CASA CRISTO GARDENS IN GUADALAJARA, JALISCO, MEXICO. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Landscape Architecture in The Department of Landscape Architecture by Marcela De Obaldia B.Arch., Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara, 1998 May 2002 DEDICATION To my parents, Idalia and José, for encouraging me to be always better. To my family, for their support, love, and for having faith in me. To Alejandro, for his unconditional help, and commitment. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all the people in the Department of Landscape Architecture for helping me to recognize the sensibility, kindness, and greatness behind a landscape, and the noble tasks that a landscape architect has in shaping them. -

Asteroid Regolith Weathering: a Large-Scale Observational Investigation

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2019 Asteroid Regolith Weathering: A Large-Scale Observational Investigation Eric Michael MacLennan University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation MacLennan, Eric Michael, "Asteroid Regolith Weathering: A Large-Scale Observational Investigation. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5467 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Eric Michael MacLennan entitled "Asteroid Regolith Weathering: A Large-Scale Observational Investigation." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Geology. Joshua P. Emery, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jeffrey E. Moersch, Harry Y. McSween Jr., Liem T. Tran Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Asteroid Regolith Weathering: A Large-Scale Observational Investigation A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Eric Michael MacLennan May 2019 © by Eric Michael MacLennan, 2019 All Rights Reserved.