WHAT WAS WRONG with DRED SCOTT, WHAT's RIGHT ABOUT Brownt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2003 Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power Dennis J. Hutchinson Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dennis J. Hutchinson, "Two Cheers for Judicial Restraint: Justice White and the Role of the Supreme Court Justice White and the Exercise of Judicial Power," 74 University of Colorado Law Review 1409 (2003). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO CHEERS FOR JUDICIAL RESTRAINT: JUSTICE WHITE AND THE ROLE OF THE SUPREME COURT DENNIS J. HUTCHINSON* The death of a Supreme Court Justice prompts an account- ing of his legacy. Although Byron R. White was both widely admired and deeply reviled during his thirty-one-year career on the Supreme Court of the United States, his death almost a year ago inspired a remarkable reconciliation among many of his critics, and many sounded an identical theme: Justice White was a model of judicial restraint-the judge who knew his place in the constitutional scheme of things, a jurist who fa- cilitated, and was reluctant to override, the policy judgments made by democratically accountable branches of government. The editorial page of the Washington Post, a frequent critic during his lifetime, made peace post-mortem and celebrated his vision of judicial restraint.' Stuart Taylor, another frequent critic, celebrated White as the "last true believer in judicial re- straint."2 Judge David M. -

Book Review: History of the Supreme Court of the United States: the Taney Period, 1836–1864 by Carl B

Nebraska Law Review Volume 54 | Issue 4 Article 6 1975 Book Review: History of the Supreme Court of the United States: The Taney Period, 1836–1864 by Carl B. Swishert James A. Lake Sr. University of Nebraska College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr Recommended Citation James A. Lake Sr., Book Review: History of the Supreme Court of the United States: The Taney Period, 1836–1864 by Carl B. Swishert, 54 Neb. L. Rev. 756 (1975) Available at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nlr/vol54/iss4/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Book Review History of the Supreme Court of the United States, The Taney Period,1836-1864-by Carl B. Swishert Reviewed by James A. Lake, Sr.* In 1955 Congress established a permanent committee to adminis- ter projects funded by a bequest from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes.' The Act established as a first priority the preparation of "a history of the Supreme Court of the United States . ." by "one or more scholars of distinction ....-2 When completed that history will include twelve volumes, each covering a specific period of the Court's history. The volume being reviewed is the third vol- ume published. The first two volumes, published in 1971, covered respectively the years from the Court's beginning to 1801 and the years 1864-1888. -

Frederick Douglass

Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection AMERICAN CRISIS BIOGRAPHIES Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph. D. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Historic Monographs Collection Zbe Hmcrican Crisis Biographies Edited by Ellis Paxson Oberholtzer, Ph.D. With the counsel and advice of Professor John B. McMaster, of the University of Pennsylvania. Each I2mo, cloth, with frontispiece portrait. Price $1.25 net; by mail» $i-37- These biographies will constitute a complete and comprehensive history of the great American sectional struggle in the form of readable and authoritative biography. The editor has enlisted the co-operation of many competent writers, as will be noted from the list given below. An interesting feature of the undertaking is that the series is to be im- partial, Southern writers having been assigned to Southern subjects and Northern writers to Northern subjects, but all will belong to the younger generation of writers, thus assuring freedom from any suspicion of war- time prejudice. The Civil War will not be treated as a rebellion, but as the great event in the history of our nation, which, after forty years, it is now clearly recognized to have been. Now ready: Abraham Lincoln. By ELLIS PAXSON OBERHOLTZER. Thomas H. Benton. By JOSEPH M. ROGERS. David G. Farragut. By JOHN R. SPEARS. William T. Sherman. By EDWARD ROBINS. Frederick Douglass. By BOOKER T. WASHINGTON. Judah P. Benjamin. By FIERCE BUTLER. In preparation: John C. Calhoun. By GAILLARD HUNT. Daniel Webster. By PROF. C. H. VAN TYNE. Alexander H. Stephens. BY LOUIS PENDLETON. John Quincy Adams. -

Report of the Decision of the Supreme Court of the United States

Library of Congress Report of the decision of the Supreme court of the United States REPORT OF THE DECISION OF THE Supreme Court of the United States, AND THE OPINIONS OF THE JUDGES THEREOF, IN THE CASE OF DRED SCOTT VERSUS JOHN F. A. SANDFORD. DECEMBER TERM, 1856. BY BENJAMIN C. HOWARD, FROM THE NINETEENTH VOLUME OF HOWARD'S REPORTS. WASHINGTON: CORNELIUS WENDELL, PRINTER. 1857. REPORT OF THE DECISION OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES, AND THE OPINIONS OF THE JUDGES THEREOF, IN THE CASE OF DRED SCOTT VERSUS JOHN F. A. SANDFORD. DECEMBER TERM, 1856. BY BENJAMIN C. HOWARD, FROM THE NINETEENTH VOLUME OF HOWARD'S REPORTS. WASHINGTON: CORNELIUS WENDELL, PRINTER. 1857. LC Report of the decision of the Supreme court of the United States http://www.loc.gov/resource/llst.027 Library of Congress SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES. DECEMBER TERM, 1856. DRED SCOTT VERSUS JOHN F. A. SANDFORD. Dred Scott, Plaintiff in Error , v. John F. A. Sandford. This case was brought up, by writ of error, from the Circuit Court of the United States for the district of Missouri. It was an action of trespass vi et armis instituted in the Circuit Court by Scott against Sandford. Prior to the institution of the present suit, an action was brought by Scott for his freedom in the Circuit Court of St. Louis county, (State court,) where there was a verdict and judgment in his favor. On a writ of error to the Supreme Court of the State, the judgment below was reversed, and the case remanded to the Circuit Court, where it was continued to await the decision of the case now in question. -

Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait Paul R

Louisiana Law Review Volume 43 | Number 4 Symposium: Maritime Personal Injury March 1983 Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait Paul R. Baier Louisiana State University Law Center Repository Citation Paul R. Baier, Edward Douglas White: Frame for a Portrait, 43 La. L. Rev. (1983) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol43/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V ( TI DEDICATION OF PORTRAIT EDWARD DOUGLASS WHITE: FRAME FOR A PORTRAIT* Oration at the unveiling of the Rosenthal portrait of E. D. White, before the Louisiana Supreme Court, October 29, 1982. Paul R. Baier** Royal Street fluttered with flags, we are told, when they unveiled the statue of Edward Douglass White, in the heart of old New Orleans, in 1926. Confederate Veterans, still wearing the gray of '61, stood about the scaffolding. Above them rose Mr. Baker's great bronze statue of E. D. White, heroic in size, draped in the national flag. Somewhere in the crowd a band played old Southern airs, soft and sweet in the April sunshine. It was an impressive occasion, reported The Times-Picayune1 notable because so many venerable men and women had gathered to pay tribute to a man whose career brings honor to Louisiana and to the nation. Fifty years separate us from that occasion, sixty from White's death. -

Supreme Court Database Code Book Brick 2018 02

The Supreme Court Database Codebook Supreme Court Database Code Book brick_2018_02 CONTRIBUTORS Harold Spaeth Michigan State University College of Law Lee Epstein Washington University in Saint Louis Ted Ruger University of Pennsylvania School of Law Sarah C. Benesh University of Wisconsin - Milwaukee Department of Political Science Jeffrey Segal Stony Brook University Department of Political Science Andrew D. Martin University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts Document Crafted On October 17, 2018 @ 11:53 1 of 128 10/17/18, 11:58 AM The Supreme Court Database Codebook Table of Contents INTRODUCTORY 1 Introduction 2 Citing to the SCDB IDENTIFICATION VARIABLES 3 SCDB Case ID 4 SCDB Docket ID 5 SCDB Issues ID 6 SCDB Vote ID 7 U.S. Reporter Citation 8 Supreme Court Citation 9 Lawyers Edition Citation 10 LEXIS Citation 11 Docket Number BACKGROUND VARIABLES 12 Case Name 13 Petitioner 14 Petitioner State 15 Respondent 16 Respondent State 17 Manner in which the Court takes Jurisdiction 18 Administrative Action Preceeding Litigation 19 Administrative Action Preceeding Litigation State 20 Three-Judge District Court 21 Origin of Case 22 Origin of Case State 23 Source of Case 24 Source of Case State 2 of 128 10/17/18, 11:58 AM The Supreme Court Database Codebook 25 Lower Court Disagreement 26 Reason for Granting Cert 27 Lower Court Disposition 28 Lower Court Disposition Direction CHRONOLOGICAL VARIABLES 29 Date of Decision 30 Term of Court 31 Natural Court 32 Chief Justice 33 Date of Oral Argument 34 Date of Reargument SUBSTANTIVE -

Aa000368.Pdf (12.17Mb)

Anthrax Vaccine n Water Wars n Debating the Draft THE AMERICAN $2.50 June 2003 The magazine for a strong America MILITARY “For God and Country since 1919 Fabulous destinations. 50 Exceptional accommodations. And now, a new level of personal service. ©2006 Travelocity.com LP.All rights reserved. Travelocity and the Stars Design are trademarks of Travelocity.com LP. LP.All CST#2056372- rights reserved.Travelocity.com and the Stars Design are trademarks of Travelocity.com ©2006 Travelocity Introducing the 2006 Cruise Collection from AARP Passport powered by Travelocity.® Make your next cruise even more memorable when you book with AARP Passport powered by Travelocity. The 2006 Cruise Collection offers more than 40 sailings with Specially Trained AARP Passport Representatives – STARs – to make certain your voyage is smooth and enjoyable. AARP members also enjoy other exclusive benefits on a wide range of itineraries; each specially selected for you and delivered by trusted AARP Passport travel providers. Your next cruise sets sail at www.aarp.org/cruisecollection28. Trusted Travel | 1.888.291.1762 | www.aarp.org/cruisecollection28 Not an AARP member yet? Visit us online to join today. AARP Passport powered by Travelocity may require a minimum number of staterooms to be booked on these sailings in order for a STAR to be onboard. In the event that a STAR will not be sailing, passengers will be notified prior to departure. contents June 2006 • Vol. 160, No. 6 12 When Heroes Come Home Hurt 4 Vet Voice The Legion, the Pentagon and local 8 Commander’s Message communities must reach out to a 10 Big Issues new generation of severely wounded veterans. -

Slavery and the Commerce Clause, 1837-1852 Kirk Scott

The Two-Edged Sword: Slavery and the Commerce Clause, 1837-1852 Kirk Scott Between 1837 and 1852, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Roger B. Taney was severely divided over the scope of national authority to regulate interstate commerce. Although the Taney Court decided only one case that directly involved the question of slavery and interstate commerce (Groves v. Slaughter}, the purpose of this paper is to explore the Court's treatment of interstate commerce during this period and the influence of the growing slavery controversy on that treatment. The potential nationalizing power of the commerce clause--power that could restrict, prevent, or promote the interstate slave trade and transform slavery into a national, constitutional issue--was an important factor in the Taney Court's disjointed, divided treatment of interstate commerce during this period, when the issue of national authority was rendered politically dangerous by the slavery controversy. National uniformity through the congressional commerce power had the potential to both restrict and expand the "peculiar institution." The commerce clause may have been the most effective constitutional instrument the Court had for allocating power between the states and the nation.1 Three essential questions that arose over interstate commerce and slavery were: (1} Was federal authority exclusive? (2} Did commerce include transportation of persons? (3} Were slaves persons or property? The first two questions emerged in the Marshall-era commerce clause cases. The philosophy of commercial nationalism was victorious, if cau tious, during these years, but new conditions, political and physical, were to bring this nationalism into question in the years ahead. -

Fedresourcestutorial.Pdf

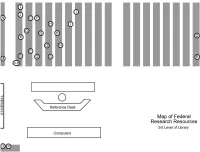

Guide to Federal Research Resources at Westminster Law Library (WLL) Revised 08/31/2011 A. United States Code – Level 3 KF62 2000.A2: The United States Code (USC) is the official compilation of federal statutes published by the Government Printing Office. It is arranged by subject into fifty chapters, or titles. The USC is republished every six years and includes yearly updates (separately bound supplements). It is the preferred resource for citing statutes in court documents and law review articles. Each statute entry is followed by its legislative history, including when it was enacted and amended. In addition to the tables of contents and chapters at the front of each volume, use the General Indexes and the Tables volumes that follow Title 50 to locate statutes on a particular topic. Relevant libguide: Federal Statutes. • Click and review Publication of Federal Statutes, Finding Statutes, and Updating Statutory Research tabs. B. United States Code Annotated - Level 3 KF62.5 .W45: Like the USC, West’s United States Code Annotated (USCA) is a compilation of federal statutes. It also includes indexes and table volumes at the end of the set to assist navigation. The USCA is updated more frequently than the USC, with smaller, integrated supplement volumes and, most importantly, pocket parts at the back of each book. Always check the pocket part for updates. The USCA is useful for research because the annotations include historical notes and cross-references to cases, regulations, law reviews and other secondary sources. LexisNexis has a similar set of annotated statutes titled “United States Code Service” (USCS), which Westminster Law Library does not own in print. -

“White”: the Judicial Abolition of Native Slavery in Revolutionary Virginia and Its Racial Legacy

ABLAVSKY REVISED FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 4/13/2011 1:24 PM COMMENT MAKING INDIANS “WHITE”: THE JUDICIAL ABOLITION OF NATIVE SLAVERY IN REVOLUTIONARY VIRGINIA AND ITS RACIAL LEGACY † GREGORY ABLAVSKY INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1458 I. THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF INDIAN SLAVERY IN VIRGINIA .............. 1463 A. The Origins of Indian Slavery in Early America .................. 1463 B. The Legal History of Indian Slavery in Virginia .................. 1467 C. Indians, Africans, and Colonial Conceptions of Race ........... 1473 II. ROBIN V. HARDAWAY, ITS PROGENY, AND THE LEGAL RECONCEPTUALIZATION OF SLAVERY ........................................... 1476 A. Indian Freedom Suits and Racial Determination ...................................................... 1476 B. Robin v. Hardaway: The Beginning of the End ................. 1480 1. The Statutory Claims ............................................ 1481 2. The Natural Law Claims ....................................... 1484 3. The Outcome and the Puzzle ............................... 1486 C. Robin’s Progeny ............................................................. 1487 † J.D. Candidate, 2011; Ph.D. Candidate, 2014, in American Legal History, Univer- sity of Pennsylvania. I would like to thank Sarah Gordon, Daniel Richter, Catherine Struve, and Michelle Banker for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of this Comment; Richard Ross, Michael Zuckerman, and Kathy Brown for discussions on the work’s broad contours; and -

The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law

Civil War Book Review Winter 2011 Article 4 The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law. Xi Wang Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr Recommended Citation Wang, Xi (2011) "The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law.," Civil War Book Review: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 . DOI: 10.31390/cwbr.13.1.05 Available at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cwbr/vol13/iss1/4 Wang: The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Review Wang, Xi Winter 2011 Konig, David Thomas (ed.) and Paul Finkelman and Christopher Alan Bracey (eds.). The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law.. Ohio University Press, $54.95 ISBN 978-0-8214-1912-0 Examining Dred Scott’s Impact and Legacy Few Supreme Court cases have attained the level of notoriety as the Dred Scott case. Even fewer have attracted such a widespread and persistent attention from scholars across academic disciplines. The Dred Scott Case: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Race and Law presents the latest product of such an attention. The volume is a collection of essays originally presented at a Washington University symposium to commemorate the case’s 150th anniversary. Divided into four categories, the 14 essays explore the history of the case and its historical and contemporary implications. As far as the historical details or constitutional interpretations of the case are concerned, little new ground has been broken, but these essays have collectively expanded the context of the case and greatly enriched our understanding of its impact, then and now. -

The Imperial President ...And His Discontents

2012_7_9 ups_cover61404-postal.qxd 6/19/2012 9:58 PM Page 1 July 9, 2012 $4.99 FOSTER ON BS LOU CANNON on Rodney King The Imperial . and His President . Discontents John Yoo Jonah Goldberg Andrew C. McCarthy Kevin D. Williamson $4.99 28 0 74820 08155 6 www.nationalreview.com base_milliken-mar 22.qxd 6/19/2012 4:07 PM Page 1 Never Be On The Wrong Side Of The Stock Market Again re you tired of building your portfolio and seeing it wither But cracks started showing in late March. IBD noted distribution A in a punishing market downtrend? Read Investor’s Business days were piling up on the major indexes. On March 28 - just one Daily® every day and you’ll stay in step with the market. day after the market hit a new high - IBD told readers the uptrend was under pressure, which presented a proper time to book some IBD uses 27 market cycles of history-proven analysis and rules profits, cut any losses and begin raising cash. Five days later to interpret the daily price and volume changes in the market further heavy selling indicated the market was in a new correction. indexes. Then we clearly tell you each day in The Big Picture market column if stocks are rising, falling, or changing course. IBD is not always perfect. But we don’t argue with the market and we quickly correct any missteps. On April 25, the S&P 500 You should be buying when the market is rising. But when offered a tentative sign that the correction was over.