3 Groundwork and Foundations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sloping and Benching Systems

Trenching and Excavation Operations SLOPING AND BENCHING SYSTEMS OBJECTIVES Upon the completion of this section, the participant should be able to: 1. Describe the difference between maximum allowable slope and actual slope. 2. Observe how the angle of various sloped systems varies with soil type. 3. Evaluate layered systems to determine the proper trench slope. 4. Illustrate how shield systems and sloping systems interface in combination systems. ©HMTRI 2000 Page 42 Trenching REV1 Trenching and Excavation Operations SLOPING SYSTEMS If enough surface room is available, sloping or benching the trench walls will offer excellent protection without any additional equipment. Cutting the slope of the excavation back to its prescribed angle will allow the forces of cohesion (if present) and internal friction to hold the soil together and keep it from flowing downs the face of the trench. The soil type primarily determines the excavation angle. Sloping a method of protecting employees from caveins by excavating to form sides of an excavation that are inclined away from the excavations so as to prevent caveins. In practice, it may be difficult to accurately determine these sloping angles. Most of the time, the depth of the trench is known or can easily be determined. Based on the vertical depth, the amount of cutback on each side of the trench can be calculated. A formula to calculate these cutback distances will be included with each slope diagram. NOTE: Remember, the beginning of the cutback distance begins at the toe of the slope, not the center of the trench. Accordingly, the cutback distance will be the same regardless of how wide the trench is at the bottom. -

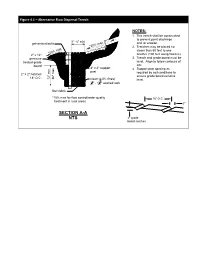

SECTION A-A NTS 2" Grade Board Notches

Figure 4.1 – Alternative Flow Dispersal Trench NOTES: 1. This trench shall be constructed to prevent point discharge 1' - 6" min galvanized bolts and /or erosion. *20% max 2. Trenches may be placed no closer than 50 feet to one *20% max 2" x 12" another (100 feet along flowline). pressure 3. Trench and grade board must be treated grade level. Align to follow contours of board site. 4" x 4" support 4. Support post spacing as post required by soil conditions to 2" x 2" notches ensure grade board remains 18" O.C. 36" max 12" min. clean (< 5% fines) level. 3 1 4" - 1 2" washed rock filter fabric *15% max for flow control/water quality 18" O.C. treatment in rural areas 2" SECTION A-A NTS 2" grade board notches Figure 4.2 – Pipe Compaction Design and Backfill O.D. O.D. limits of pipe W (see note 4) 3' max. 3' max. compaction limit of pipe zone 1' - 0" bedding material for flexible 1' - 0" pipe (see 0.15 O.D. min. note 6) B O.D. limits of pipe compaction 0.65 O.D. min. foundation level A* gravel backfill gravel backfill for for pipe bedding foundations when specified * A = 4" min., 27" I.D. and under 6" min., over 27" I.D. A. Metal and Concrete Pipe Bedding for Flexible Pipe span span span 3' max Flexible Pipe NOTES: 3' max 3' max 1. Provide uniform support under barrels. 1'-0" 2. Hand tamp under haunches. 3. Compact bedding material to 95% max. -

Frequency and Magnitude of Selected Historical Landslide Events in The

Chapter 9 Frequency and Magnitude of Selected Historical Landslide Events in the Southern Appalachian Highlands of North Carolina and Virginia: Relationships to Rainfall, Geological and Ecohydrological Controls, and Effects Richard M. Wooten , Anne C. Witt , Chelcy F. Miniat , Tristram C. Hales , and Jennifer L. Aldred Abstract Landsliding is a recurring process in the southern Appalachian Highlands (SAH) region of the Central Hardwood Region. Debris fl ows, dominant among landslide processes in the SAH, are triggered when rainfall increases pore-water pressures in steep, soil-mantled slopes. Storms that trigger hundreds of debris fl ows occur about every 9 years and those that generate thousands occur about every 25 years. Rainfall from cyclonic storms triggered hundreds to thousands of debris R. M. Wooten (*) Geohazards and Engineering Geology , North Carolina Geological Survey , 2090 US Highway 70 , Swannanoa , NC 28778 , USA e-mail: [email protected] A. C. Witt Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy , Division of Geology and Mineral Resources , 900 Natural Resources Drive, Suite 500 , Charlottesville , VA 22903 , USA e-mail: [email protected] C. F. Miniat Coweeta Hydrologic Lab , Center for Forest Watershed Research, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station , 3160 Coweeta Lab Road , Otto , NC 28763 , USA e-mail: [email protected] T. C. Hales Hillslope Geomorphology , School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University , Main Building, Park Place , Cardiff CF10 3AT , UK e-mail: [email protected] J. L. Aldred Department of Geography and Earth Sciences , University of North Carolina at Charlotte , 9201 University City Blvd. , Charlotte , NC 28223 , USA e-mail: [email protected] © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 203 C.H. -

Division 2 Earthwork

Division 2 Earthwork 2-01 Clearing, Grubbing, and Roadside Cleanup 2-01.1 Description The Contractor shall clear, grub, and clean up those areas staked or described in the Special Provisions. This Work includes protecting from harm all trees, bushes, shrubs, or other objects selected to remain. “Clearing” means removing and disposing of all unwanted material from the surface, such as trees, brush, down timber, or other natural material. “Grubbing” means removing and disposing of all unwanted vegetative matter from underground, such as sod, stumps, roots, buried logs, or other debris. “Roadside cleanup”, whether inside or outside the staked area, means Work done to give the roadside an attractive, finished appearance. “Debris” means all unusable natural material produced by clearing, grubbing, or roadside cleanup. 2-01.2 Disposal of Usable Material and Debris The Contractor shall meet all requirements of state, county, and municipal regulations regarding health, safety, and public welfare in the disposal of all usable material and debris. The Contractor shall dispose of all debris by one or more of the disposal methods described below. 2-01.2(1) Disposal Method No. 1 – Open Burning The open burning of residue resulting from land clearing is restricted by Chapter 173-425 of the Washington Administrative Code (WAC). No commercial open burning shall be conducted without authorization from the Washington State Department of Ecology or the appropriate local air pollution control authority. All burning operations shall be strictly in accordance with these authorizations. 2-01.2(2) Disposal Method No. 2 – Waste Site Debris shall be hauled to a waste site obtained and provided by the Contractor in accordance with Section 2-03.3(7)C. -

Trench Blasting with DYNAMITE a TRADITION of INNOVATION

Trench Blasting with DYNAMITE A TRADITION OF INNOVATION Dyno Nobel’s roots reach back to every significant in- novation in explosives safety and technology. Today, Dyno Nobel supplies a full line of explosives products and blasting services to mines, quarries and contractors in nearly every part of the world. DYNAMITE PRODUCT OF CHOICE FOR TRENCH BLASTING One explosive product has survived the test of time to become a true classic in the industry. DYNAMITE! The dynamite products manufactured today by Dyno Nobel are similar to Alfred Nobel’s original 1860s invention yet, in selected applications, they outperform any other commercial explosives on the market. The high energy, reliability and easy loading characteristics of dynamite make it the product of choice for difficult and demand- ing trench blasting jobs. Look to Unigel®, Dynomax Pro® and Unimax® to make trench blasting as effective and efficient as it can be. DISCLAIMER The information set forth herein is provided for informational purposes only. No representation or warranty is made or intended by DYNO NOBEL INC. or its affiliates as to the applicability of any procedures to any par- ticular situation or circumstance or as to the completeness or accuracy of any information contained herein. User assumes sole responsibility for all results and consequences. ® Cover photo depicts a trench blast using Primacord detonating cord, MS ® Connectors and Unimax dynamite. SAFE BLASTING REMINDERS Blasting safety is our first priority. Review these remind- ers frequently and make safety your first priority, too. • Dynamite products will provide higher energy value than alternate products used for trenching due to their superior energy, velocity and weight strength. -

Fact Sheet: Trenching and Excavation Safety

Fact sheet Trenching and excavation safety Between 2016 and 2019, three Minnesota workers died in a trench, excavation or ground collapse. Cave-ins pose the greatest risk and are much more likely than other excavation-related accidents to result in worker fatalities. Minnesota law requires employers to provide a workplace free of recognized hazards that may cause serious injury or death. This includes the trenching and excavation requirements of 29 CFR 1926.651 and 1926.652. An excavation is any man-made cut, cavity, trench or depression in an earth surface, formed by earth removal. A trench – or a trench excavation – is a narrow excavation (in relation to its length) made below the surface of the ground; in general, the depth is greater than the width, but the width of a trench (measured at the bottom) is not greater than 15 feet. Dangers of trenching and excavation In addition to cave-ins, other potential hazards include falls, falling loads, hazardous atmospheres and incidents involving mobile equipment. Two cubic yards of soil can weigh about 6,000 pounds or as much as a small car. An unprotected trench is an early grave. Do not enter an unprotected trench. Trench safety measures Trenches five feet deep or greater require a protective system unless the excavation is made entirely in stable rock. If the trench is fewer than five feet deep, a competent person may determine a protective system is not required. Trenches 20 feet deep or greater require that the protective system be designed by a registered professional engineer or be based on tabulated data prepared and/or approved by a registered professional engineer in accordance with 1926.652(b) and (c). -

Slope Stability

Slope stability Causes of instability Mechanics of slopes Analysis of translational slip Analysis of rotational slip Site investigation Remedial measures Soil or rock masses with sloping surfaces, either natural or constructed, are subject to forces associated with gravity and seepage which cause instability. Resistance to failure is derived mainly from a combination of slope geometry and the shear strength of the soil or rock itself. The different types of instability can be characterised by spatial considerations, particle size and speed of movement. One of the simplest methods of classification is that proposed by Varnes in 1978: I. Falls II. Topples III. Slides rotational and translational IV. Lateral spreads V. Flows in Bedrock and in Soils VI. Complex Falls In which the mass in motion travels most of the distance through the air. Falls include: free fall, movement by leaps and bounds, and rolling of fragments of bedrock or soil. Topples Toppling occurs as movement due to forces that cause an over-turning moment about a pivot point below the centre of gravity of the unit. If unchecked it will result in a fall or slide. The potential for toppling can be identified using the graphical construction on a stereonet. The stereonet allows the spatial distribution of discontinuities to be presented alongside the slope surface. On a stereoplot toppling is indicated by a concentration of poles "in front" of the slope's great circle and within ± 30º of the direction of true dip. Lateral Spreads Lateral spreads are disturbed lateral extension movements in a fractured mass. Two subgroups are identified: A. -

Our Broad (TUNNEL) Vision

5 OUR BROAD Royal Boskalis Westminster N.V. Rosmolenweg 20 PO Box 43 (TUNNEL) VISION 3350 AA Papendrecht The Netherlands [email protected] Immersed tunnel execution brings Boskalis’ fields of expertise Our in-house experts are from a broad range of disciplines T +31 78 6969000 together. that span the capabilities necessary for immersed tunnel F +31 78 6969555 activities, including: Construction is technically complex and involves an extreme www.boskalis.com degree of accuracy. Design of the elements is governed by Geotechnics temporary phases, meaning that the early involvement of Hydraulic Processes an experienced contractor is crucial to producing optimal Maritime Engineering solutions. Environmental Management IMMERSED Boskalis combines both operational and engineering They work in close cooperation with structural design capabilities and is able to handle the entire installation partners and combine insight about the design process with process, from feasibility studies to completion. a thorough understanding of the practicalities of works, which often leads to opportunities for clients. TUNNELS Immersed tunnel execution involves our core activities of dredging, rock placing, inland infrastructure and towage. Boskalis has the skills, resources and experience to engineer Our fleet of specially developed marine equipment enables and execute all marine activities involved in any immersed us to execute them safely and with the required precision. tunnel project, anywhere. OUR SOLUTIONS 1. Construction of building dock and water management 6. Outfitting 2. Dredging the tunnel trench 7. Immersion management and survey (including closure 3. Laying the gravel or sand-flow foundation joint) 4. Towage 8. Locking fill, trench backfill and rock protection 5. Transportation overseas 9. -

Trenching Precautions to Take Before Trenching and Tips on Safety

Safety Matters is intended to promote discussions of safety issues among underground construction professionals. You should always read and understand the operator’s manual before operating any equipment. For additional information, please e-mail [email protected]. INFORMATION/FACTS TOPIC: • Trench sides can cave in up to a distance of 3/4 x the depth of the trench. For example, if the trench is 4 feet (1.2 Trenching m) deep, the cave-in can start up to 3 feet (0.9 m) away from trench. POTENTIAL HAZARDS • Trenchers can react if the chain hits an underground • Caught in obstruction such as a tree branch or concrete footing. On • Struck by pedestrian machines, this can cause the handles to be • Laceration forced downward suddenly. • Drawn into • Machine will move when digging starts. • Buried hazards TALES FROM THE TRENCH • Falls onto • The injured was using a shovel on the right side of the digging chain to cave off the trench side and allow the PRECAUTIONS digging chain to pull soil from the trench. The accident • ALWAYS have all underground utilities located prior to occurred when the injured got too close and attempted to digging. Know and follow local regulations for excavating near step across the trench with his left leg. His foot slipped utilities. down the trench side and into the digging chain. His leg • Stay away and keep others at least 6 feet (1.8 m) away from was amputated below the knee and he had severe tissue machine and moving parts of machine. Stop machine if damage to his thigh. -

Soil, Plant and Water Reference Methods for the Western Region1

SOIL, PLANT AND WATER REFERENCE METHODS FOR THE WESTERN REGION 1 2005 3rd Edition Dr. Ray Gavlak Dr. Donald Horneck Dr. Robert O. Miller 1 From: Plant, Soil and Water Reference Methods for the Western Region. 1994. R. G. Gavlak, D. A. Horneck, and R. O. Miller. WREP 125. PREFACE This manual has been developed as a guide of standard analytical methods for agricultural laboratories for use in the Western Region, byt the Western Coordinating Committee on Nutrient Management. This publication an update of Plant, Soil and Water Reference Methods for the Western Region , 1994, (WREP 125) written by Dr. Ray Gavlak formerly of the University of Alaska, Dr. Donald Horneck of Oregon State University, and Dr. Robert O. Miller of Colorado State University. These represent accepted methods for the analysis of soil and plant samples and were selected for the express purpose of identifying common methods on which a group of agricultural laboratories analytical results can be statistically evaluated. We would like to thank all those individuals who have contributed to this manual. The specific soil, plant and water analytical methods listed represent those analytical procedures that are recommended for use in the current North American Proficiency Testing Program organized by the Soil Science Society of America. We encourage all suggestions and comments from participating laboratories for improving this manual for future publication. The authors would like to thank Dr. Byron Vaughan of MDS Harris Laboratory Services, Dr. Kelly Belden of the University of Wyoming for reviewing this publication. WREP-125, 3 rd Edition TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Quality Assurance in the Agricultural Laboratory ..................................... -

Gabion Basket Installation Construction Design Standards

Gabion Basket Installation Construction Design Standards, suggest that a 500mm trench be dug to allow for future excavations in front of the wall, this also gets below the frost layer, and provides a toe in to stop the baskets slipping, (This toe in is not normally used within the structural calculations for the standard designs). Another reason for this is that the top soil contains organic matter that may rot or compress. The majority of installations for short walls are started at ground level, it is down to the customer to make a decision on site looking at the ground conditions. The worst material for gabion walls to sit on is soft clay, if the ground is likely to sink under baskets weight, a gabion retaining wall may not be possible. 100-200mm of hardcore (type 1) should be compacted with a vibrating plate as a footing for the gabion wall. If 200mm was put in the 500mm deep trench the baskets would start 300mm below ground. Baskets should be lent back at 6 degrees. The Face of a gabion wall can be flushed or stepped. On taller walls baskets are stepped back to equalize the pressure between the heel and toe of the wall. Gabions can be cut on site to achieve your required dimensions. The standard thickness for walls up to 3m in height is 3mm. 4mm is the architectural spec, 5mm is what we would refer to as the military spec or for use on higher walls. For inexperienced installers a 4mm face can be added for walls 3m and below to reduce the risk of bulging. -

Trenching and Shoring Guidelines

Trenching and Shoring Guidelines August 2020 TABLE of CONTENTS I. General II. Definition III. Requirements IV. Soil Types V. Test Methods and Evaluating Soil Types VI. Ingress and Egress VII. Exposure to Falling Loads VIII. Warning Systems for Mobile Equipment IX. Hazardous Atmospheres and Confined Spaces X. Standing Water and Water Accumulation XI. Benching, Sloping, Shoring, and Shielding Requirements A. Benching B. Sloping C. Shoring D. Shielding XII. Training and Recordkeeping Appendix A: Trench Inspection and Entry Authorization Form Trenching and Shoring Guidelines I. General Excavating is recognized as one of the most hazardous operations. This standard shall provide guidance for University employees who perform excavations on property owned by the University of Northern Colorado (UNC). II. Definitions Aluminum hydraulic shoring: An engineered shoring system comprised of aluminum hydraulic cylinders (cross braces), used in conjunction with vertical rails (uprights) or horizontal rails (walers). Such a system is designed specifically to support the sidewalls of an excavation and prevent cave-ins. Benching: A method used to protect employees from cave-ins by excavating the sides of an excavation to form one or a series of horizontal levels or steps, usually with vertical or near-vertical surfaces between levels. Cave-in: The separation of a mass of soil or rock material from the side of an excavation, or the loss of soil from under a trench shield or support system, and its sudden movement into the excavation, either by falling or sliding, in sufficient quantity so that it could entrap, bury, or otherwise injure and immobilize a person. Competent Person: An individual who is capable of identifying existing and predictable hazards or working conditions that is hazardous, unsanitary, or dangerous to employees, and who has authorization to take prompt corrective measures to eliminate or control these hazards and conditions.