USBR Engineering Geology Field Manual Volume 1 Chapter 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strike and Dip Refer to the Orientation Or Attitude of a Geologic Feature. The

Name__________________________________ 89.325 – Geology for Engineers Faults, Folds, Outcrop Patterns and Geologic Maps I. Properties of Earth Materials When rocks are subjected to differential stress the resulting build-up in strain can cause deformation. Depending on the material properties the result can either be elastic deformation which can ultimately lead to the breaking of the rock material (faults) or ductile deformation which can lead to the development of folds. In this exercise we will look at the various types of deformation and how geologists use geologic maps to understand this deformation. II. Strike and Dip Strike and dip refer to the orientation or attitude of a geologic feature. The strike line of a bed, fault, or other planar feature, is a line representing the intersection of that feature with a horizontal plane. On a geologic map, this is represented with a short straight line segment oriented parallel to the strike line. Strike (or strike angle) can be given as either a quadrant compass bearing of the strike line (N25°E for example) or in terms of east or west of true north or south, a single three digit number representing the azimuth, where the lower number is usually given (where the example of N25°E would simply be 025), or the azimuth number followed by the degree sign (example of N25°E would be 025°). The dip gives the steepest angle of descent of a tilted bed or feature relative to a horizontal plane, and is given by the number (0°-90°) as well as a letter (N, S, E, W) with rough direction in which the bed is dipping. -

Sloping and Benching Systems

Trenching and Excavation Operations SLOPING AND BENCHING SYSTEMS OBJECTIVES Upon the completion of this section, the participant should be able to: 1. Describe the difference between maximum allowable slope and actual slope. 2. Observe how the angle of various sloped systems varies with soil type. 3. Evaluate layered systems to determine the proper trench slope. 4. Illustrate how shield systems and sloping systems interface in combination systems. ©HMTRI 2000 Page 42 Trenching REV1 Trenching and Excavation Operations SLOPING SYSTEMS If enough surface room is available, sloping or benching the trench walls will offer excellent protection without any additional equipment. Cutting the slope of the excavation back to its prescribed angle will allow the forces of cohesion (if present) and internal friction to hold the soil together and keep it from flowing downs the face of the trench. The soil type primarily determines the excavation angle. Sloping a method of protecting employees from caveins by excavating to form sides of an excavation that are inclined away from the excavations so as to prevent caveins. In practice, it may be difficult to accurately determine these sloping angles. Most of the time, the depth of the trench is known or can easily be determined. Based on the vertical depth, the amount of cutback on each side of the trench can be calculated. A formula to calculate these cutback distances will be included with each slope diagram. NOTE: Remember, the beginning of the cutback distance begins at the toe of the slope, not the center of the trench. Accordingly, the cutback distance will be the same regardless of how wide the trench is at the bottom. -

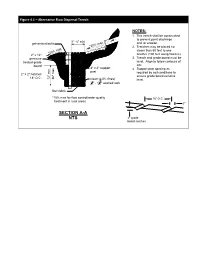

SECTION A-A NTS 2" Grade Board Notches

Figure 4.1 – Alternative Flow Dispersal Trench NOTES: 1. This trench shall be constructed to prevent point discharge 1' - 6" min galvanized bolts and /or erosion. *20% max 2. Trenches may be placed no closer than 50 feet to one *20% max 2" x 12" another (100 feet along flowline). pressure 3. Trench and grade board must be treated grade level. Align to follow contours of board site. 4" x 4" support 4. Support post spacing as post required by soil conditions to 2" x 2" notches ensure grade board remains 18" O.C. 36" max 12" min. clean (< 5% fines) level. 3 1 4" - 1 2" washed rock filter fabric *15% max for flow control/water quality 18" O.C. treatment in rural areas 2" SECTION A-A NTS 2" grade board notches Figure 4.2 – Pipe Compaction Design and Backfill O.D. O.D. limits of pipe W (see note 4) 3' max. 3' max. compaction limit of pipe zone 1' - 0" bedding material for flexible 1' - 0" pipe (see 0.15 O.D. min. note 6) B O.D. limits of pipe compaction 0.65 O.D. min. foundation level A* gravel backfill gravel backfill for for pipe bedding foundations when specified * A = 4" min., 27" I.D. and under 6" min., over 27" I.D. A. Metal and Concrete Pipe Bedding for Flexible Pipe span span span 3' max Flexible Pipe NOTES: 3' max 3' max 1. Provide uniform support under barrels. 1'-0" 2. Hand tamp under haunches. 3. Compact bedding material to 95% max. -

Frequency and Magnitude of Selected Historical Landslide Events in The

Chapter 9 Frequency and Magnitude of Selected Historical Landslide Events in the Southern Appalachian Highlands of North Carolina and Virginia: Relationships to Rainfall, Geological and Ecohydrological Controls, and Effects Richard M. Wooten , Anne C. Witt , Chelcy F. Miniat , Tristram C. Hales , and Jennifer L. Aldred Abstract Landsliding is a recurring process in the southern Appalachian Highlands (SAH) region of the Central Hardwood Region. Debris fl ows, dominant among landslide processes in the SAH, are triggered when rainfall increases pore-water pressures in steep, soil-mantled slopes. Storms that trigger hundreds of debris fl ows occur about every 9 years and those that generate thousands occur about every 25 years. Rainfall from cyclonic storms triggered hundreds to thousands of debris R. M. Wooten (*) Geohazards and Engineering Geology , North Carolina Geological Survey , 2090 US Highway 70 , Swannanoa , NC 28778 , USA e-mail: [email protected] A. C. Witt Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy , Division of Geology and Mineral Resources , 900 Natural Resources Drive, Suite 500 , Charlottesville , VA 22903 , USA e-mail: [email protected] C. F. Miniat Coweeta Hydrologic Lab , Center for Forest Watershed Research, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station , 3160 Coweeta Lab Road , Otto , NC 28763 , USA e-mail: [email protected] T. C. Hales Hillslope Geomorphology , School of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University , Main Building, Park Place , Cardiff CF10 3AT , UK e-mail: [email protected] J. L. Aldred Department of Geography and Earth Sciences , University of North Carolina at Charlotte , 9201 University City Blvd. , Charlotte , NC 28223 , USA e-mail: [email protected] © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 203 C.H. -

Division 2 Earthwork

Division 2 Earthwork 2-01 Clearing, Grubbing, and Roadside Cleanup 2-01.1 Description The Contractor shall clear, grub, and clean up those areas staked or described in the Special Provisions. This Work includes protecting from harm all trees, bushes, shrubs, or other objects selected to remain. “Clearing” means removing and disposing of all unwanted material from the surface, such as trees, brush, down timber, or other natural material. “Grubbing” means removing and disposing of all unwanted vegetative matter from underground, such as sod, stumps, roots, buried logs, or other debris. “Roadside cleanup”, whether inside or outside the staked area, means Work done to give the roadside an attractive, finished appearance. “Debris” means all unusable natural material produced by clearing, grubbing, or roadside cleanup. 2-01.2 Disposal of Usable Material and Debris The Contractor shall meet all requirements of state, county, and municipal regulations regarding health, safety, and public welfare in the disposal of all usable material and debris. The Contractor shall dispose of all debris by one or more of the disposal methods described below. 2-01.2(1) Disposal Method No. 1 – Open Burning The open burning of residue resulting from land clearing is restricted by Chapter 173-425 of the Washington Administrative Code (WAC). No commercial open burning shall be conducted without authorization from the Washington State Department of Ecology or the appropriate local air pollution control authority. All burning operations shall be strictly in accordance with these authorizations. 2-01.2(2) Disposal Method No. 2 – Waste Site Debris shall be hauled to a waste site obtained and provided by the Contractor in accordance with Section 2-03.3(7)C. -

FM 5-410 Chapter 2

FM 5-410 CHAPTER 2 Structural Geology Structural geology describes the form, pat- secondary structural features. These secon- tern, origin, and internal structure of rock dary features include folds, faults, joints, and and soil masses. Tectonics, a closely related schistosity. These features can be identified field, deals with structural features on a and m appeal in the field through site inves- larger regional, continental, or global scale. tigation and from remote imagery. Figure 2-1, page 2-2, shows the major plates of the earth’s crust. These plates continually Section I. Structural Features undergo movement as shown by the arrows. in Sedimentary Rocks Figure 2-2, page 2-3, is a more detailed repre- sentation of plate tectonic theory. Molten material rises to the earth’s surface at BEDDING PLANES midoceanic ridges, forcing the oceanic plates Structural features are most readily recog- to diverge. These plates, in turn, collide with nized in the sedimentary rocks. They are adjacent plates, which may or may not be of normally deposited in more or less regular similar density. If the two colliding plates are horizontal layers that accumulate on top of of approximately equal density, the plates each other in an orderly sequence. Individual will crumple, forming mountain range along deposits within the sequence are separated the convergent zone. If, on the other hand, by planar contact surfaces called bedding one of the plates is more dense than the other, planes (see Figure 1-7, page 1-9). Bedding it will be subducted, or forced below, the planes are of great importance to military en- lighter plate, creating an oceanic trench along gineers. -

3 Groundwork and Foundations

P1: JZW/JZZ BY032-03 BY032-Emmitt BY032-v1.cls September 13, 2004 9:6 3 Groundwork and Foundations The foundation of a building is that part of walls, piers and columns in direct contact with, and transmitting loads to, the ground. The building founda- tion is sometimes referred to as the artificial foundation, and the ground on which it bears as the natural foundation. Early buildings were founded on rock or firm ground; it was not until the beginning of the twentieth century that concrete was increasingly used as a foundation base for walls. With the introduction of local and then national building regulations, standard forms of concrete foundations have become accepted practice in the UK, along with more rigorous investigation of the nature and bearing capacity of soils and bedrock. 3.1 Functional requirements The primary functional requirement of a foundation is strength and stability. Strength and stability The combined, dead, imposed and wind loads on a building must be transmit- ted to the ground safely, without causing deflection or deformation of the build- ing or movement of the ground that would impair the stability of the building and/or neighbouring structures. Foundations should also be designed and constructed to resist any movements of the subsoil. Foundations should be designed so that any settlement is both limited and uniform under the whole of the building. Some settlement of a building on a soil foundation is inevitable. As the building is erected the loads placed on the foundation increase and the soil is compressed. This settlement should be limited to avoid damage to service pipes and drains connected to the building. -

Trench Blasting with DYNAMITE a TRADITION of INNOVATION

Trench Blasting with DYNAMITE A TRADITION OF INNOVATION Dyno Nobel’s roots reach back to every significant in- novation in explosives safety and technology. Today, Dyno Nobel supplies a full line of explosives products and blasting services to mines, quarries and contractors in nearly every part of the world. DYNAMITE PRODUCT OF CHOICE FOR TRENCH BLASTING One explosive product has survived the test of time to become a true classic in the industry. DYNAMITE! The dynamite products manufactured today by Dyno Nobel are similar to Alfred Nobel’s original 1860s invention yet, in selected applications, they outperform any other commercial explosives on the market. The high energy, reliability and easy loading characteristics of dynamite make it the product of choice for difficult and demand- ing trench blasting jobs. Look to Unigel®, Dynomax Pro® and Unimax® to make trench blasting as effective and efficient as it can be. DISCLAIMER The information set forth herein is provided for informational purposes only. No representation or warranty is made or intended by DYNO NOBEL INC. or its affiliates as to the applicability of any procedures to any par- ticular situation or circumstance or as to the completeness or accuracy of any information contained herein. User assumes sole responsibility for all results and consequences. ® Cover photo depicts a trench blast using Primacord detonating cord, MS ® Connectors and Unimax dynamite. SAFE BLASTING REMINDERS Blasting safety is our first priority. Review these remind- ers frequently and make safety your first priority, too. • Dynamite products will provide higher energy value than alternate products used for trenching due to their superior energy, velocity and weight strength. -

Fact Sheet: Trenching and Excavation Safety

Fact sheet Trenching and excavation safety Between 2016 and 2019, three Minnesota workers died in a trench, excavation or ground collapse. Cave-ins pose the greatest risk and are much more likely than other excavation-related accidents to result in worker fatalities. Minnesota law requires employers to provide a workplace free of recognized hazards that may cause serious injury or death. This includes the trenching and excavation requirements of 29 CFR 1926.651 and 1926.652. An excavation is any man-made cut, cavity, trench or depression in an earth surface, formed by earth removal. A trench – or a trench excavation – is a narrow excavation (in relation to its length) made below the surface of the ground; in general, the depth is greater than the width, but the width of a trench (measured at the bottom) is not greater than 15 feet. Dangers of trenching and excavation In addition to cave-ins, other potential hazards include falls, falling loads, hazardous atmospheres and incidents involving mobile equipment. Two cubic yards of soil can weigh about 6,000 pounds or as much as a small car. An unprotected trench is an early grave. Do not enter an unprotected trench. Trench safety measures Trenches five feet deep or greater require a protective system unless the excavation is made entirely in stable rock. If the trench is fewer than five feet deep, a competent person may determine a protective system is not required. Trenches 20 feet deep or greater require that the protective system be designed by a registered professional engineer or be based on tabulated data prepared and/or approved by a registered professional engineer in accordance with 1926.652(b) and (c). -

Slope Stability

Slope stability Causes of instability Mechanics of slopes Analysis of translational slip Analysis of rotational slip Site investigation Remedial measures Soil or rock masses with sloping surfaces, either natural or constructed, are subject to forces associated with gravity and seepage which cause instability. Resistance to failure is derived mainly from a combination of slope geometry and the shear strength of the soil or rock itself. The different types of instability can be characterised by spatial considerations, particle size and speed of movement. One of the simplest methods of classification is that proposed by Varnes in 1978: I. Falls II. Topples III. Slides rotational and translational IV. Lateral spreads V. Flows in Bedrock and in Soils VI. Complex Falls In which the mass in motion travels most of the distance through the air. Falls include: free fall, movement by leaps and bounds, and rolling of fragments of bedrock or soil. Topples Toppling occurs as movement due to forces that cause an over-turning moment about a pivot point below the centre of gravity of the unit. If unchecked it will result in a fall or slide. The potential for toppling can be identified using the graphical construction on a stereonet. The stereonet allows the spatial distribution of discontinuities to be presented alongside the slope surface. On a stereoplot toppling is indicated by a concentration of poles "in front" of the slope's great circle and within ± 30º of the direction of true dip. Lateral Spreads Lateral spreads are disturbed lateral extension movements in a fractured mass. Two subgroups are identified: A. -

Semester -3 Civil Engineering

CIVIL ENGINEERING SEMESTER -3 CIVIL ENGINEERING Year of MECHANICS OF CATEGORY L T P CREDIT CET201 Introduction SOLIDS PCC 3 1 0 4 2019 Preamble: Mechanics of solids is one of the foundation courses in the study of structural systems. The course provides the fundamental concepts of mechanics of deformable bodies and helps students to develop their analytical and problem solving skills. The course introduces students to the various internal effects induced in structural members as well as their deformations due to different types of loading. After this course students will be able to determine the stress, strain and deformation of loaded structural elements. Prerequisite: EST 100 Engineering Mechanics Course Outcomes: After the completion of the course the student will be able to Prescribed Course Description of Course Outcome Outcome learning level Recall the fundamental terms and theorems associated with CO1 Remembering mechanics of linear elastic deformable bodies. Explain the behavior and response of various structural CO2 Understanding elements under various loading conditions. Apply the principles of solid mechanics to calculate internal stresses/strains, stress resultants and strain energies in CO3 Applying structural elements subjected to axial/transverse loadsand bending/twisting moments. Choose appropriate principles or formula to find the elastic CO4 constants of materials making use of the information Applying available. Perform stress transformations, identify principal planes/ CO5 stresses and maximum shear stress at a point -

The Mylonite Issue 16 November 2008

INSIDE • News from the Chair • Special Announcements • Faculty • Alumni The Newsletter of the Geological Sciences Dept. Calif. State Polytechnic University Pomona, Calif. The Mylonite Issue 16 November 2008 NEWS FROM THE CHAIR NOTE FROM THE CHAIR 2008 Spending was severely curtailed. The Mylonite Once again, greetings to each and every one of was one of those “non-essential” items. It was only you! This will be the last letter I write to you all as Chair through collective Department persistence, the immense of the Geological Sciences Department. It is time for a help of Ms. Mary Jo Gruca, the College’s Development change in leadership, new ideas and new approaches. I Director, and the University’s Office of Advancement will end my tenure as Chair at the commencement of the were we able to send the Mylonite out to all of you. It spring quarter of 2009. At that time, Dr. Jon Nourse will was no easy task. take over the responsibilities. It has been a true pleasure All faculty searches within the College of and a privilege to have served you all for so long. Science were cancelled. Geology had already begun Reflecting back on this past year, there is no doubt it was advertising and was receiving applications when our my most difficult year as Chair. The report below is far search for a Sedimentary Geologist was ended. As of from up beat and only peripherally related to my this writing, the Sedimentary Geology position remains stepping down as chair. vacant and there is no faculty search underway.