A Conversation with Vassar Clements by Frank Goodman (Puremusic.Com, 8/2004)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blues Notes October 2015

VOLUME TWENTY, NUMBER TEN • OCTOBER 2015 SELWYN BIRCHWOOD MARIA BSO Halloween Party MULDAUR Sat. Oct 31st Saturday @ 7 pm $10 Oct. 3rd 21st Saloon @ 6 pm Zoo Bar Lincoln, NE Oct. 1st ..................................................................Red Elvises ($10) Oct. 4th (Sunday @ 4 pm) ...The Nebraska Blues Challenge Finals ($5) Oct. 8th ................................................................ Eleanor Tallie ($10) Oct. 15th ................................................................ John Primer ($12) NEBRASKA BLUES CHALLENGE Oct. 22nd ...........................................Cedrick Burnside Project ($10) Oct. 29th .....................Gracie Curran & Her High Falutin’ Band ($10) FINALS COMPETITION Oct. 31st (Saturday @ 7 pm)..................... Halloween Party with the Selwyn Birchwood Band ($10) 21st Saloon, Omaha, NE Nov. 5th ................................................. The Bart Walker Band ($10) Sunday, Oct. 4th @ 4 pm • $5 cover Nov. 7th (Saturday @ 9 pm) ................................Sinners and Saints Nov. 12th ..................................................... Crystal Shawanda ($10) — More info inside — Nov. 19th ............................................. The Scottie Miller Band ($10) PAGE 2 BLUES NEWS • BLUES SOCIETY OF OMAHA Please consider switching to the GREEN VERSION of Blues Notes. You will be saving the planet while saving BSO some expense. Contact Becky at [email protected] to switch to e-mail newsletter delivery and get the scoop days before snail mail members! BLUES ON THE RADIO: -

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid

Diana Davies Photograph Collection Finding Aid Collection summary Prepared by Stephanie Smith, Joyce Capper, Jillian Foley, and Meaghan McCarthy 2004-2005. Creator: Diana Davies Title: The Diana Davies Photograph Collection Extent: 8 binders containing contact sheets, slides, and prints; 7 boxes (8.5”x10.75”x2.5”) of 35 mm negatives; 2 binders of 35 mm and 120 format negatives; and 1 box of 11 oversize prints. Abstract: Original photographs, negatives, and color slides taken by Diana Davies. Date span: 1963-present. Bulk dates: Newport Folk Festival, 1963-1969, 1987, 1992; Philadelphia Folk Festival, 1967-1968, 1987. Provenance The Smithsonian Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections acquired portions of the Diana Davies Photograph Collection in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when Ms. Davies photographed for the Festival of American Folklife. More materials came to the Archives circa 1989 or 1990. Archivist Stephanie Smith visited her in 1998 and 2004, and brought back additional materials which Ms. Davies wanted to donate to the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives. In a letter dated 12 March 2002, Ms. Davies gave full discretion to the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage to grant permission for both internal and external use of her photographs, with the proviso that her work be credited “photo by Diana Davies.” Restrictions Permission for the duplication or publication of items in the Diana Davies Photograph Collection must be obtained from the Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections. Consult the archivists for further information. Scope and Content Note The Davies photographs already held by the Rinzler Archives have been supplemented by two more recent donations (1998 and 2004) of additional photographs (contact sheets, prints, and slides) of the Newport Folk Festival, the Philadelphia Folk Festival, the Poor People's March on Washington, the Civil Rights Movement, the Georgia Sea Islands, and miscellaneous personalities of the American folk revival. -

Sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 Songs, 14.2 Hours, 1.62 GB

Page 1 of 8 ...sunday.Sept.06.Overnight 261 songs, 14.2 hours, 1.62 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Go Now! 3:15 The Magnificent Moodies The Moody Blues 2 Waiting To Derail 3:55 Strangers Almanac Whiskeytown 3 Copperhead Road 4:34 Shut Up And Die Like An Aviator Steve Earle And The Dukes 4 Crazy To Love You 3:06 Old Ideas Leonard Cohen 5 Willow Bend-Julie 0:23 6 Donations 3 w/id Julie 0:24 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 7 Wheels Of Love 2:44 Anthology Emmylou Harris 8 California Sunset 2:57 Old Ways Neil Young 9 Soul of Man 4:30 Ready for Confetti Robert Earl Keen 10 Speaking In Tongues 4:34 Slant 6 Mind Greg Brown 11 Soap Making-Julie 0:23 12 Volunteer 1 w/ID- Tony 1:20 KSZN Broadcast Clips 13 Quittin' Time 3:55 State Of The Heart Mary Chapin Carpenter 14 Thank You 2:51 Bonnie Raitt Bonnie Raitt 15 Bootleg 3:02 Bayou Country (Limited Edition) Creedence Clearwater Revival 16 Man In Need 3:36 Shoot Out the Lights Richard & Linda Thompson 17 Semicolon Project-Frenaudo 0:44 18 Let Him Fly 3:08 Fly Dixie Chicks 19 A River for Him 5:07 Bluebird Emmylou Harris 20 Desperadoes Waiting For A Train 4:19 Other Voices, Too (A Trip Back To… Nanci Griffith 21 uw niles radio long w legal id 0:32 KSZN Broadcast Clips 22 Cold, Cold Heart 5:09 Timeless: Hank Williams Tribute Lucinda Williams 23 Why Do You Have to Torture Me? 2:37 Swingin' West Big Sandy & His Fly-Rite Boys 24 Madmax 3:32 Acoustic Swing David Grisman 25 Grand Canyon Trust-Terry 0:38 26 Volunteer 2 Julie 0:48 KSZN Broadcast Clips Julie 27 Happiness 3:55 So Long So Wrong Alison Krauss & Union Station -

John Lee Hooker: King of the Boogie Opens March 29 at the Grammy Museum® L.A

JOHN LEE HOOKER: KING OF THE BOOGIE OPENS MARCH 29 AT THE GRAMMY MUSEUM® L.A. LIVE CONTINUING THE 100TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BIRTH OF LEGENDARY GRAMMY®-WINNING BLUESMAN JOHN LEE HOOKER, TRAVELING EXHIBIT WILL FEATURE RARE RECORDINGS AND UNIQUE ITEMS FROM THE HOOKER ESTATE; HOOKER'S DAUGHTERS, DIANE HOOKER-ROAN AND ZAKIYA HOOKER, TO APPEAR AT MUSEUM FOR SPECIAL OPENING NIGHT PROGRAM LOS ANGELES, CALIF. (MARCH 6, 2018) —To continue commemorating what would have been legendary GRAMMY®-winning blues artist John Lee Hooker’s 100th birthday, the GRAMMY Museum® will open John Lee Hooker: King Of The Boogie in the Special Exhibits Gallery on the second floor on Thursday, March 29, 2018. On the night of the opening, Diane Hooker-Roan and Zakiya Hooker, daughters of the late bluesman, will appear at the GRAMMY Museum for a special program. Presented in conjunction with the John Lee Hooker Estate and Craft Recordings, the exhibit originally opened at GRAMMY Museum Mississippi—Hooker's home state—in 2017, the year of Hooker's centennial. On display for a limited time only through June 2018, the exhibit will include, among other items: • A rare 1961 Epiphone Zephyr—one of only 13 made that year—identical to the '61 Zephyr played by John Lee Hooker. Plus, a prototype of Epiphone's soon-to-be-released Limited Edition 100th Anniversary John Lee Hooker Zephyr signature guitar • Instruments such as the Gibson ES-335, Hohner HJ5 Jazz, and custom Washburn HB35, all of which were played by Hooker • The Best Traditional Blues Recording GRAMMY Hooker won, with Bonnie Raitt, for "I'm In The Mood" at the 32nd Annual GRAMMY Awards in 1990 • Hooker's Best Traditional Blues Album GRAMMY for Don't Look Back, which was co-produced by Van Morrison and Mike Kappus and won at the 40th Annual GRAMMY Awards in 1998 • A letter to Hooker from former President Bill Clinton • The program from Hooker's memorial service, which took place on June 27, 2001, in Oakland, Calif. -

Dan Hicks’ Caucasian Hip-Hop for Hicksters Published February 19, 2015 | Copyright @2015 Straight Ahead Media

Dan Hicks’ Caucasian Hip-Hop For Hicksters Published February 19, 2015 | Copyright @2015 Straight Ahead Media Author: Steve Roby Showdate : Feb. 18, 2015 Performance Venue : Yoshi’s Oakland Bay Area legend Dan Hicks performed to a sold-out crowd at Yoshi’s on Wednesday. The audience was made up of his loyal fans (Hicksters) who probably first heard his music on KSAN, Jive 95, back in 1969. At age 11, Hicks started out as a drummer, and was heavily influenced by jazz and Dixieland music, often playing dances at the VFW. During the folk revival of the ‘60s, he picked up a guitar, and would go to hootenannies while attending San Francisco State. Hicks began writing songs, an eclectic mix of Western swing, folk, jazz, and blues, and eventually formed Dan Hicks and his Hot Licks. His offbeat humor filtered its way into his stage act. Today, with tongue firmly planted in cheek, Hicks sums up his special genre as “Caucasian hip-hop.” Over four decades later, Hicks still delivers a unique performance, and Wednesday’s show was jammed with many great moments. One of the evenings highlights was the classic “I Scare Myself,” which Hicks is still unclear if it’s a love song when he wrote it back in 1969. “I was either in love, or I’d just eaten a big hashish brownie,” recalled Hicks. Adding to the song’s paranoia theme, back-up singers Daria and Roberta Donnay dawned dark shades while Benito Cortez played a chilling violin solo complete with creepy horror movie sound effects. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

282 Newsletter

NEWSLETTER #282 COUNTY SALES P.O. Box 191 November-December 2006 Floyd,VA 24091 www.countysales.com PHONE ORDERS: (540) 745-2001 FAX ORDERS: (540) 745-2008 WELCOME TO OUR COMBINED CHRISTMAS CATALOG & NEWSLETTER #282 Once again this holiday season we are combining our last Newsletter of the year with our Christmas catalog of gift sugges- tions. There are many wonderful items in the realm of BOOKs, VIDEOS and BOXED SETS that will make wonderful gifts for family members & friends who love this music. Gift suggestions start on page 10—there are some Christmas CDs and many recent DVDs that are new to our catalog this year. JOSH GRAVES We are saddened to report the death of the great dobro player, Burkett Graves (also known as “Buck” ROU-0575 RHONDA VINCENT “Beautiful Graves and even more as “Uncle Josh”) who passed away Star—A Christmas Collection” This is the year’s on Sept. 30. Though he played for other groups like Wilma only new Bluegrass Christmas album that we are Lee & Stoney Cooper and Mac Wiseman, Graves was best aware of—but it’s a beauty that should please most known for his work with Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs, add- Bluegrass fans and all ing his dobro to their already exceptional sound at the height Rhonda Vincent fans. of their popularity. The first to really make the dobro a solo Rhonda has picked out a instrument, Graves had a profound influence on Mike typical program of mostly standards (JINGLE Auldridge and Jerry Douglas and the legions of others who BELLS, AWAY IN A have since made the instrument a staple of many Bluegrass MANGER, LET IT bands everywhere. -

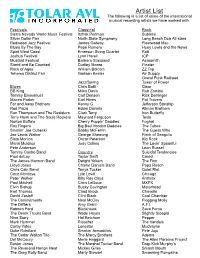

Artist List the Following Is a List of Some of the International Musical Recording Artists We Have Worked With

Artist List The following is a list of some of the international musical recording artists we have worked with. Festivals Classical Rock Sierra Nevada World Music Festival Itzhak Perlman Sublime Silver Dollar Fair North State Symphony Long Beach Dub All-stars Redwood Jazz Festival James Galway Fleetwood Mac Blues By The Bay Pepe Romero Huey Lewis and the News Spirit West Coast Emerson String Quartet Ratt Joshua Festival Lynn Harell ICP Mustard Festival Barbara Streisand Aerosmith Stand and Be Counted Dudley Moore Floater Rock of Ages William Bolcom ZZ Top Tehema District Fair Garison Keeler Air Supply Grand Funk Railroad Jazz/Swing Tower of Power Blues Chris Botti Gwar BB King Miles Davis Rob Zombie Tommy Emmanuel Carl Denson Rick Derringer Maceo Parker Earl Hines Pat Travers Far and Away Brothers Kenny G Jefferson Starship Rod Piaza Eddie Daniels Allman Brothers Ron Thompson and The Resistors Clark Terry Iron Butterfly Terry Hank and The Souls Rockers Maynard Ferguson Tesla Norton Buffalo Cherry Poppin’ Daddies Foghat Roy Rogers Big Bad Voodoo Daddies The Tubes Smokin’ Joe Cubecki Bobby McFerrin The Guess Who Joe Lewis Walker George Shearing Flock of Seagulls Sista Monica Oscar Peterson Kid Rock Maria Muldaur Judy Collins The Lovin’ Spoonful Pete Anderson Leon Russel Tommy Castro Band Country Suicidal Tendencies Paul deLay Taylor Swift Creed The James Harmon Band Dwight Yokem The Fixx Lloyd Jones Charlie Daniels Band Papa Roach Chris Cain Band Tanya Tucker Quiet Riot Coco Montoya Lyle Lovitt Chicago Peter Welker Billy Ray Cirus Anthrax Paul Mitchell Chris LeDoux MXPX Elvin Bishop Bucky Covington Motorhead Earl Thomas Chad Brock Chavelle David Zasloff Clint Black Coal Chamber The Commitments Neal McCoy Flogging Molly The Drifters Amy Grant A.F.I. -

Blueink Newsletter April 2016

B L U E I N K APRIL 2016 Gator By the Bay Brings Musicians Together in Exciting Pairings Now in its 15th year, Gator By the Bay, May 5-8, 2016, has become a wildly popular San Diego festival tradition known for presenting an eclectic mix of musical styles and a fun- filled atmosphere. Wander among the festival’s seven stages and you can listen to everything from authentic Louisiana Cajun and Zydeco music to Chicago and West Coast Blues, from Latin to Rockabilly and Swing. In recent years, Gator By the Bay has also earned a stand-out reputation for bringing together stellar combinations of musicians in innovative mash-up performances, presenting musical groupings you won’t hear anywhere else. This year is no exception. On Saturday, May 7, San Diego’s own multiple gold guitarist Johnny Vernazza will share the Mardi Gras Stage with blues greats Roy Rogers and John Németh. Often lauded as the “Master of the Slide Guitar”, Roy Rogers’ distinctive style is instantly recognizable. He’s shared duets with such greats as John Lee Hooker and Allen Toussaint, and teamed up with the likes of Norton Buffalo and Ray Manzarek. Harmonica virtuoso, vocalist and songwriter John Németh has multiple Blues Music Awards nominations to his name, and his album, ‘Memphis Grease’, won Best Soul Blues Album at the 2015 Blues Music Awards. He has been nominated for the Blues Music Awards 2016 B.B. King Entertainer of the Year Award, to be given out on May 5. Other notable combined artists’ performances include Sugaray Rayford, Alabama Mike & the Drop Ins with harmonica master Rick Estrin and harmonica and guitar whiz-kid Jon Atkinson on Friday evening, May 6, and Jon Atkinson with Rick Estrin and Fabulous Thunderbird alumna Kim Wilson on Saturday, May 7. -

Appreciation of Popular Music 1/2

FREEHOLD REGIONAL HIGH SCHOOL DISTRICT OFFICE OF CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION MUSIC DEPARTMENT APPRECIATION OF POPULAR MUSIC 1/2 Grade Level: 10-12 Credits: 2.5 each section BOARD OF EDUCATION ADOPTION DATE: AUGUST 30, 2010 SUPPORTING RESOURCES AVAILABLE IN DISTRICT RESOURCE SHARING APPENDIX A: ACCOMMODATIONS AND MODIFICATIONS APPENDIX B: ASSESSMENT EVIDENCE APPENDIX C: INTERDISCIPLINARY CONNECTIONS Course Philosophy “Musical training is a more potent instrument than any other, because rhythm, harmony, and melody find their way into the inward place of our soul, on which they mightily fasten, imparting grace, and making the soul of him who is educated graceful.” - Plato We believe our music curriculum should provide quality experiences that are musically meaningful to the education of all our students. It should help them discover, understand and enjoy music as an art form, an intellectual endeavor, a medium of self-expression, and a means of social growth. Music is considered basic to the total educational program. To each new generation this portion of our heritage is a source of inspiration, enjoyment, and knowledge which helps to shape a way of life. Our music curriculum enriches and maintains this life and draws on our nation and the world for its ever- expanding course content, taking the student beyond the realm of the ordinary, everyday experience. Music is an art that expresses emotion, indicates mood, and helps students to respond to their environment. It develops the student’s character through its emphasis on responsibility, self-discipline, leadership, concentration, and respect for and awareness of the contributions of others. Music contains technical, psychological, artistic, and academic concepts. -

Maria Muldaur

CLASSIC CUTS MARIA MULDAUR MARIA MULDAUR EXHIBIT ven if you didn’t know at the time crying all the way up to the gig and he’d say, of the release of this album in 1973 ‘Okay, dry your eyes and wash your face. who Muldaur was, if you flipped We’re on in half an hour.’ And he was just a the LP over and just glanced at very supportive little brother to me". the twelve names and faces who The album was not only well received it supported her on this album, you produced a single. And what a single! “Yes, it Ecouldn’t help but be impressed. happened to have a little hit called ‘Midnight Let me give you a few of those. We have: At The You-Know-What’ on it". Mac Rebennack or, as he is best known, Dr She’s talking about ‘Midnight at the Oasis’, John. A formidable boogie and blues pianist of course. This was her first big hit which is with a lovable growl of a voice; there’s Ry still seen as ‘the’ Muldaur song and is popular, Cooder, an excellent musician and guitar- even now with so many people. toting genius who brought the Buena Vista “With everybody – it’s amazing. It’s so Social Club to wider notice; Clarence White, a weird to me” she said. “Not a gig goes by gifted guitarist and folk-rock pioneer who was that several people don’t come up and tell part of The Byrds; David Grisman a bluegrass me exactly where they were when they first specialist, Grateful Dead and Jerry Garcia heard that. -

Rock the Blues Away

ROCK THESE BLUES AWAY. The Recordings of John Lee Hooker since 1981 ROCK THESE BLUES AWAY The Recordings Of John Lee Hooker Since 1981 By Gary Hearn (Feb. 2006) Introduction In 1992 Les Fancout’s sessionography of John Lee Hooker – “Boogie Chillen” – was published in booklet form by Blues & Rhythm magazine (ed. Tony Burke). This pamphlet is intended to update Les’ work with all the known Hooker sessions since 1981. Though details on other, earlier, sessions have come to light through recent releases, I have excluded them from the scope of my research and it is left to others to publish those corrections and additions elsewhere. The recordings listed here come from the final phase of John’s career during what is known as the Rosebud era, the name of his management company. To my imperfect mind, the best – and darkest – of them found release on the “Boom Boom” album put out by Pointblank in 1993. This was also a period when blues artists were called upon to provide benevolent cameos to artists better known in the mainstream. John took part in many such sessions with varying degrees of success; whatever the finished product, his contributions were immediately recognisable. The compact discs in this survey are, as far as I can tell, the first UK issue shown listed in order of catalogue number for ease of cross-reference to the sessionography. Because record companies re-issue, re-package and licence their recordings, subsequent issues are not considered. None of the cd-singles listed are still available and are shown merely in evidence of the penetration of the “John Lee Hooker” brand.