Island Girl in a Rock-And-Roll World an Interview with June Millington by Theo Gonzalves and Gayle Wald

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blues Notes October 2015

VOLUME TWENTY, NUMBER TEN • OCTOBER 2015 SELWYN BIRCHWOOD MARIA BSO Halloween Party MULDAUR Sat. Oct 31st Saturday @ 7 pm $10 Oct. 3rd 21st Saloon @ 6 pm Zoo Bar Lincoln, NE Oct. 1st ..................................................................Red Elvises ($10) Oct. 4th (Sunday @ 4 pm) ...The Nebraska Blues Challenge Finals ($5) Oct. 8th ................................................................ Eleanor Tallie ($10) Oct. 15th ................................................................ John Primer ($12) NEBRASKA BLUES CHALLENGE Oct. 22nd ...........................................Cedrick Burnside Project ($10) Oct. 29th .....................Gracie Curran & Her High Falutin’ Band ($10) FINALS COMPETITION Oct. 31st (Saturday @ 7 pm)..................... Halloween Party with the Selwyn Birchwood Band ($10) 21st Saloon, Omaha, NE Nov. 5th ................................................. The Bart Walker Band ($10) Sunday, Oct. 4th @ 4 pm • $5 cover Nov. 7th (Saturday @ 9 pm) ................................Sinners and Saints Nov. 12th ..................................................... Crystal Shawanda ($10) — More info inside — Nov. 19th ............................................. The Scottie Miller Band ($10) PAGE 2 BLUES NEWS • BLUES SOCIETY OF OMAHA Please consider switching to the GREEN VERSION of Blues Notes. You will be saving the planet while saving BSO some expense. Contact Becky at [email protected] to switch to e-mail newsletter delivery and get the scoop days before snail mail members! BLUES ON THE RADIO: -

A Conversation with Vassar Clements by Frank Goodman (Puremusic.Com, 8/2004)

A Conversation with Vassar Clements by Frank Goodman (Puremusic.com, 8/2004) Perhaps like many who will enjoy the interview that follows, among my first recollections of Vassar’s playing is the 1972 Nitty Gritty Dirt Band recording Will the Circle Be Unbroken. As long ago as that seems (and is), he’d already been at it for over twenty years! In 1949, although only 14 years old and still in school, he began playing with Bill Monroe, the father of bluegrass. Aside from a few years off early on to check out some other things, Vassar’s been playing music professionally ever since. He’s recognized as the most genre-bending fiddler ever. “The Father of Hillbilly Jazz” is a handle that comes from several CDs he cut at that crossroads, but you can hear jazz and blues in any of the playing he’s done. He grew up listening to big band and Dixieland, and still listens to a lot of it today. Vassar says that many of the tunes he writes or passages he’ll fly into in a solo come from half remembered horn lines deep in his musical memory. Between his beginnings with Bill Monroe and the Circle album, Clements did many years with Jim and Jesse and then years with the late and much loved John Hartford, a lifelong friend who gave him the legendary fiddle he plays today. Circle turned a whole generation of hippies and acoustic music fans on to his music, and the children of that generation are following him today, as his popularity continues to recycle. -

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2012, Pp. 69-98 Islands And

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2012, pp. 69-98 Islands and Islandness in Rock Music Lyrics Daniele Mezzana CERFE (Centro di Ricerca e Documentazione Febbraio ‘74) Rome, Italy [email protected] Aaron Lorenz Law & Society, Ramapo College New Jersey, USA [email protected] and Ilan Kelman Center for International Climate and Environmental Research - Oslo (CICERO) Oslo, Norway [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper presents a first exploration, qualitative in character, based on a review of 412 songs produced in the period 1960-2009, about islands in rock music as both social products and social tools potentially contributing to shaping ideas, emotions, will, and desires. An initial taxonomy of 24 themes clustered under five meta-themes of space, lifestyle, emotions, symbolism, and social-political relations is provided, together with some proposals for further research. Keywords: abductive method; art; islandness; rock music; social construction © 2012 Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction: Rock Music and Islands: Looking for a Link “[…] in an age when nothing is physically inaccessible or unknowable, the dream of the small, remote and undiscovered place has become so powerful” (Gillis, 2004: 148) This article presents a first exploration, qualitative in character, of how rock music lyrics and song titles portray islands, islandness, and island features. It examines the island aspects of a socio-cultural trend expressed in as far-reaching a medium as that of rock music. Here, we adopt a broad definition of ‘rock music’, including different expressions of this genre, starting with the emergence of rock in the late 1950’s to early 1960’s, and moving towards more current expressions including art rock, progressive rock, punk and reggae (Wicke, 1990; Charlton, 2003). -

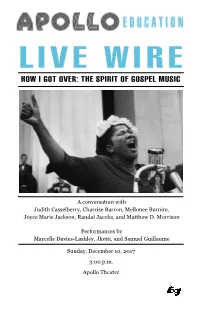

View the Program Book for How I Got Over

A conversation with Judith Casselberry, Charrise Barron, Mellonee Burnim, Joyce Marie Jackson, Randal Jacobs, and Matthew D. Morrison Performances by Marcelle Davies-Lashley, Jhetti, and Samuel Guillaume Sunday, December 10, 2017 3:00 p.m. Apollo Theater Front Cover: Mahalia Jackson; March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom 1957 LIVE WIRE: HOW I GOT OVER - THE SPIRIT OF GOSPEL MUSIC In 1963, when Mahalia Jackson sang “How I Got Over” before 250,000 protesters at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, she epitomized the sound and sentiment of Black Americans one hundred years after Emancipation. To sing of looking back to see “how I got over,” while protesting racial violence and social, civic, economic, and political oppression, both celebrated victories won and allowed all to envision current struggles in the past tense. Gospel is the good news. Look how far God has brought us. Look at where God will take us. On its face, the gospel song composed by Clara Ward in 1951, spoke to personal trials and tribulations overcome by the power of Jesus Christ. Black gospel music, however, has always occupied a space between the push to individualistic Christian salvation and community liberation in the context of an unjust society— a declaration of faith by the communal “I”. From its incubation at the turn of the 20th century to its emergence as a genre in the 1930s, gospel was the sound of Black people on the move. People with purpose, vision, and a spirit of experimentation— clear on what they left behind, unsure of what lay ahead. -

(Pdf) Download

Artist Song 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 2Pac All Eyez On Me 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes 3 Doors Down Here By Me 3 Doors Down Live For Today 3 Doors Down Citizen Soldier 3 Doors Down Train 3 Doors Down Let Me Be Myself 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 3 Doors Down Featuring Bob Seger Landing In London 38 Special If I'd Been The One 4him The Basics Of Life 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees This Gift 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 98 Degrees Feat. Stevie Wonder True To Your Heart A Flock Of Seagulls The More You Live The More You Love A Flock Of Seagulls Wishing (If I Had A Photograph Of You) A Flock Of Seagulls I Ran (So Far Away) A Great Big World Say Something A Great Big World ft Chritina Aguilara Say Something A Great Big World ftg. Christina Aguilera Say Something A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie Oogie A.R. Rahman And The Pussycat Dolls Jai Ho Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothing But A Number Aaliyah I Can Be Aaliyah I Refuse Aaliyah Never No More Aaliyah Read Between The Lines Aaliyah What If Aaron Carter Oh Aaron Aaron Carter Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Aaron Carter How I Beat Shaq Aaron Lines Love Changes Everything Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven Aaron Neville Everybody Plays The Fool Aaron Tippin Her Aaron Watson Outta Style ABC All Of My Heart ABC Poison Arrow Ad Libs The Boy From New York City Afroman Because I Got High Air -

Toshi Reagon & Biglovely

Toshi Reagon & BIGLovely “Whether playing solo or with her band, [Toshi’s] fusion of styles and forms draws listeners in, embraces them and sets them off in a rapturous, hand-raising, foot-stomping delight.” -RighteousBabe.com About Toshi Reagon and BIGLovely Toshi Reagon is a versatile singer-songwriter-guitarist, drawing on the traditions of uniquely American music: rock, blues, R&B, country, folk, spirituals and funk. Born in Atlanta and raised in Washington DC, she comes from a musical—and political—family. Both her parents were civil rights activists in the 1960s, and founding members of The Freedom Singers, a folk group that toured the country to teach people about civil rights through song as part of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. Her mother, Bernice Johnson Reagon, is also a founder of the legendary a cappella group, Sweet Honey in the Rock. Toshi has been performing since she was 17 years old. Her career really launched when Lenny Kravitz chose her, straight out of college, to open for him on his first world tour. Some of Toshi’s proudest moments include playing for her godfather Pete Seeger’s 90th birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden, and performing with the Freedom Singers at the White House, in a tribute to the music of the civil rights movement. As a composer and producer, Toshi has created original scores for dance works, collaborated on two contemporary operas, served as producer on multiple albums, and has had her own work featured in films and TV soundtracks, including HBO and PBS programs. BIGLovely did its first performance as a band in 1996. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

Elton John Page.Cdr

Elton John Music Titles Available from The Music Box, 30/31 The Lanes, Meadowhall Centre Sheffield S9 1EP Write with cheque made out to TMB Retail Music Ltd. or your card details or phone us on 0114 256 9089 Monday to Friday 10am- 8.45pm, Saturday 9am to 6.45pm or Sunday 11am to 4.30pm Elton John - Greatest Hits 1970-2002 IMP9807A £14.99 UK Postage £2.25 Your Song - Tiny Dancer - Honky Cat - Rocket Man (I Think It's Going To Be A Long, Long Time) - Crocodile Rock - Daniel - Saturday Night's Alright (For Fighting) - Goodbye Yellow Brick Road - Candle In The Wind - Bennie And The Jets - Don't Let The Sun Go Down On Me - The Bitch Is Back - Philadelphia Freedom - Someone Saved My Life Tonight - Island Girl - Don't Go Breaking My Heart - Sorry Seems To Be The Hardest Word - Blue Eyes - I'm Still Standing - I Guess That's Why They Call It The Blues - Sad Songs (Say So Much) - Nikita - Sacrifice - The One - Kiss The Bride - Can You Feel The Love Tonight - Circle Of Life - Believe - Made In England - Something About The Way You Look Tonight - Written In The Stars - I Want Love - This Train Don't Stop There Anymore - Song For Guy The Very Best Of Elton John BGP83627 £12.99 UK Postage £2.25 All the tracks from the definitive Elton John album of the same name for voice, piano and guitar chord boxes with full lyrics. Bennie And The Jets - Blue Eyes - Candle In The Wind - Crocodile Rock - Daniel - Don't Let The Sun Go Down On Me - Dont Go Breaking My Heart - Easier To Walk Away - Goodbye Yellow Brick Road - Honky Cat - I'm Still Standing - I Don't -

Come out COME

CoME OuT BEING Our IN J\cADEME: A YEAR OF Mv LIFE IN ENID, AMERICA COME OUT by Jan McDonald National Coming Out Day, October 11, is an annual event They knew I was a lesbian when they hired me to be the recognized by lesbians, gay men and bisexuals and their Chair of Education at Phillips University in the Spring of 1992, supporters as a day to celebrate the process of accepting and but I didn't know they knew. I had gone to no lengths to hide being open about their sexual orientation. Commemorating its it, but neither had I mentioned it during my three-day interview. sixth year, National Coming Out Day festivities will be held They knew my several trips to Stillwater were to see my partner across the country encouraging people to take their next step in Judy who had been hired at OSU the year before, but I didn't the coming out process. know they knew. Since Phillips is affiliated with the Disciples Several celebrities and prominent figures have come out of Christ, I was not surprised to be asked about how comfortable this year and made it easier for others to take that first step and I would be in a church-related institution. But, I must admit that come out. ·'When people like tennis greatMartina Navratilova, being asked that question by every individual who interviewed singers k.d. Lang, Janis Ian and Melissa Etheridge, media me, seemed odd. mogul David Geffen, and former Mr. Universe and Mr. Olym As I waited back in New York, negotiations regarding my pia Bob Jackson-Paris come out, they send a strong message to hiring were bogged down for over a month because of the on those in the closet that coming out and being honest about who campus debate over my sexual orientation. -

Rock Music and Representation: the Roles of Rock Culture AMS 311S // Unique No

Page 1 Rock Music and Representation: The Roles of Rock Culture AMS 311s // Unique No. 31080 Spring 2020 BUR 436A: M/W/F 11:00 am – 12:00 pm Instructor: Kate Grover // [email protected] // pronouns: she, her, hers Office Hours: BUR 408 // Monday & Wednesday, 1 pm – 2:30 pm, or by appointment Course Description What is a guitar god? Who gets to be one, and why? What are the “roles” of rock music and culture? What is rock, anyway? This is not your average rock history course. Instead, this course positions 20th and 21st century American rock music and culture as a crucial site for ongoing struggles over identity, belonging, and power. We will explore how race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability have shaped how various groups of people engage with rock and what insights these engagements provide about “the American experience” over time. How do rock artists, critics, filmmakers, and fans represent themselves and others? What do these representational strategies reveal about inclusion and exclusion in rock culture, and in American society at large? While examining rock’s players, we will also consider the roles of different rock media and institutions such as MTV, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and Rolling Stone magazine. As such, our course is divided into three units exploring different areas of representation within rock music and culture. Unit 1: Performing Rock, Performing Identity, provides an introduction to studying rock’s sounds, visuals, and texts by investigating various issues of identity within rock music and culture. Unit 2: Evaluating Rock: Writers, Critics, and Other Commentators focuses on the roles of rock critics and the stakes of writing about music. -

EASTSIDE PUNKS a Screening and Conversation Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 P.M

THEMEGUIDE EASTSIDE PUNKS A Screening and Conversation Thursday, April 22, 2021, at 7 p.m. Live via Zoom University of Southern California WHAT TO KNOW o Eastside Punks is a series of documentary shorts produced by Razorcake magazine about the first generation of East L.A. punk, circa the late 1970s and early ’80s o This event includes excerpts from Eastside Punks and a panel discussion with members of several of the featured bands: Thee Undertakers, The Brat, and the Stains o Razorcake is an L.A.-based DIY punk zine Photo: Angie Garcia ABOUT THE PARTICIPANTS Jimmy Alvarado (Eastside Punks director) has been active in East L.A.’s underground music scene since 1981 as a musician, backyard gig promoter, writer, poet, bouncer, flyer artist, photographer, podcaster, historian, and filmmaker. He has authored numerous interviews, articles, and short films spotlighting the Eastside scene. He plays guitar in the bands La Tuya and Our Band Sucks. Teresa Covarrubias was the vocalist for The Brat. Their debut EP, Attitudes, was released on The Plugz’ record label, featured contributions from John Doe and Exene from X, and is a prized item among collectors. Straight Outta East L.A., a double Photo: Edward Colver album packaging it with other rare tracks, was released in 2017. Tracy “Skull” Garcia was the bass player of Thee Undertakers. Starting off by playing local parties in 1977, they became regulars in the scene centered around the Vex. Their 1981 debut album, Crucify Me, successfully melded second-wave hardcore bite with first-wave art sensibilities, but wasn’t released until 2001 on CD and 2020 on vinyl. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas.