Transformative Relief Jackson, Simon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Everyday Saver

2018- 2019 The Everyday Saver The Student Union at Notre Dame University-Louaize (NDU) is proud to present its updates on their project: THE EVERYDAY SAVER It’s time for students, faculty, and staff members to benefit from the discounts stated below while handling your valid NDU ID Card. Terms and conditions: Discounts provided in restaurants cover the bill. Discounts are not applicable with any other promotion, offer, combo or event. Discounts should be noted on your arrival or booking to avoid confusion. Please note we will keep you updated on new upcoming offers. Restaurants AL SANIOUR 40% DISCOUNT SARBA/09222551 AM-PM 25% DISCOUNT ZOUK MIKAEL/09226622 BEIT EL SOKHN 20% DISCOUNT FROM MONDAY TO FRIDAY KASLIK/81644133 BEYT SAHEBNA 30% DISCOUNT JAL EL DIB/04724655 BLUE IVY 35% DISCOUNT MONDAY TO FRIDAY TILL 7PM, 30% ON SUSHI EVERY FRIDAY JEITA/09238472 BUFFALO WINGS& RINGS 20% DISCOUNT KASLIK/09936935 BURGER KING 15% DISCOUNT ONLY JEITA BRANCH/09224898 THE BURGER SHOP SPECIAL OFFER BALLOUNEH/09233502 CASA DELL’OLIVIO 20% DISCOUNT TAYYOUNEH/01395013 CHEZ MICHEL 10% DISCOUNT FAQRA/09300060 CHINA BOX 10% DISCOUNT EXCLUDING ONLINE DELIVERY KASLIK/09910471 DIEZE 25% WEEKDAYS, 15%WEEKENDS GHAZIR/70112344 DOUGHLICIOUS 20% DISCOUNT DINE-IN ALL BRANCHES/81271111 EL SOMBRERO 20% DISCOUNT DINE-IN ADONIS/81779664 GELATO SHOW 20% DISCOUNT, DINE-IN JOUNIEH/09642150 GO BURGER 15% DISCOUNT ZOUK MOSBEH/81414888 LA PARADERA 15% DISCOUNT BYBLOS/76737666 LE GOURMET BURGER 20% DISCOUNT ZOUK BRANCH 09271118 LE KIMONO 20% DISCOUNT KASLIK/09211999 LORD OF -

Horizon 2019

HORIZON Colonie de vacances CHAMPVILLE 2019 HORIZON 2019 CHAMPVILLE Du JEUDI 04 JUILLET AU LUNDI 26 AOÛT (8 semaines) DU LUNDI AU VENDREDI 08h30 À 13h40 4 journées d’activités internes et une sortie hebdomadaire 500 000 LL Possibilité d’accueillir vos enfants, à partir de 07h30, et de les garder en surveillance jusqu’à 15h00 (sans aucune charge supplémentaire). Inscription à Champville. Tél. : 04 913327 ext. 4-401 - Aucun remboursement en cas de désistement. Une assurance de 20 000 LL pour chaque enfant d’un autre collège. Pour une même famille : 1 enfant : 500 000 LL / 2 enfants : 900 000 LL / 3 enfants : 1 300 000 LL HORIZON EST LA COLONIE OÙ LES MONITEURS ACCOMPAGNENT VOS ENFANTS AUX 21 ATELIERS DIRIGÉS PAR DES ANIMATEURS PROFESSIONNELS ATELIERS “HORIZON” Gymnastique Danse Football Activités théâtrales Dessinons le monde Taekwondo Construis ta cabane Arts plastiques Activité Culinaire Detective work ATELIERS “HORIZON” NOUVEAUX ATELIERS Chef Pâtissier Jeux de motricité Recyclage Basket-ball Zumba Questions pour un champion Aikido Univers du modelage Jeux de compétition Jeux gonflables et trampoline Pliage “HORIZON” ÉVASION 1 SORTIE PAR SEMAINE (LES VENDREDIS) ACADÉMIE DE BASKET-BALL DU 8 JUILLET AU 26 AOÛT 2019 (8 semaines) TOUS LES LUNDIS ET MERCREDIS DE 09h00 à 13h00 4 Terrains couverts Prix : 350 000 LL/Personne Colonie + Basket-ball : 650 000 LL/Personne ACADÉMIE DE FOOTBALL DU 09 JUILLET AU 27 AOÛT 2019 (8 semaines) TOUS LES MARDIS ET JEUDIS DE 09h00 à 13h00 5 Terrains de Foot : 2 SURFACES EN GAZON 3 TERRAINS COUVERTS Prix : 350 -

Alfred Basbous

ALFRED BASBOUS Alfred Basbous was born in Rachana, Lebanon in 1924. His first exhibition in Beirut, at the Alecco Saab gallery in 1958, marked the beginning of a long and successful career as a sculptor. In 1960, he received a scholarship from the French government and became a pupil of the sculptor René Collamarini at ‘The National Fine Arts School in Paris’ (L’Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts de Paris). In 1961, his works were included in the International Sculpture Exhibition at the Musée Rodin, in Paris. From 1994 to 2004, Basbous organized the International Symposium of Sculpture in Rachana, Lebanon, where famous sculptors from around the world were invited to create, sculpt and exhibit their works alongside his own. Throughout his life, Basbous won many awards including the “Prix de l’Orient” in Beirut in 1963 and the price of Biennale in Alexandria in 1974. When he died in 2006, the President of the Lebanese Republic, in order to honor him, awarded him the “Medal of the Lebanese Order of Merit in Gold.” Basbous’s works express a lifelong exploration of the human form and its abstract properties. Focused on the aesthetic principles of shape, movement, line and material, his sculptures display a deeply ingrained sincerity and a search for the essence of beauty. Working in the tradition of sculptors such as Jean Arp, Constantin Brâncuși and Henry Moore, Alfred Basbous explores the potential of noble materials such as bronze, wood and marble to express the sensuality and purity of the human form. This aversion towards frivolous and meaningless embellishments echoes his own philosophy of simplicity and earnestness. -

Healthcare Network Providers TABLE of CONTENTS

Healthcare Network Providers TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF CONTRACTED HOSPITALS - GENERAL NETWORK 02 LIST OF CONTRACTED AMBULATORY PROVIDERS - DIAGNOSTIC CENTERS 05 LIST OF CONTRACTED AMBULATORY PROVIDERS - LABORATORY CENTERS 07 AMBULATORY AND RADIOLOGY SERVICES 10 LIST OF CONTRACTED AMBULATORY PROVIDERS - OPTOMETRY - VISION SERVICE CENTERS 11 LIST OF CONTRACTED AMBULATORY PROVIDERS - FIRST AID CENTER - PRIMARY CARE CENTER 11 LIST OF CONTRACTED AMBULATORY PROVIDERS - HOME CARE 11 LIST OF CONTRACTED AMBULATORY PROVIDERS - DENTAL CENTER 11 LIST OF CONTRACTED PHARMACIES 12 LIST OF CONTRACTED PHYSICIANS 20 HI-AD-02/ED13 1 of 26 Healthcare Network Providers List of Contracted Hospitals - General Network * For members insured under Restricted Network, American University Of Beirut Medical Center (AUBMC) and Clemenceau Medical Center (CMC) are excluded GREATER BEIRUT Address Telephone Beirut Eye & Ent Specialist Hospital Al Mathaf, Hotel Dieu St. 01/423110-111 Hopital Libanais Geitaoui - Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Ashrafieh, Geitawi St. 01/577177 Hotel-Dieu De France Ashrafieh, Hotel Dieu St. 01/615300 - 01/615400 St. George Hospital - University Medical Center Ashrafieh, Rmeil St. After Sagesse University 1287 University Medical Center - Rizk Hospital Ashrafieh, Zahar St. 01/200800 Al Zahraa Hospital Bir Hassan, Jnah, Facing Hotel Galleria 01/853409-10 Beirut General Hospital Bir Hassan, Jnah 01/850236 Rafik Hariri University Hospital Rhuh Bir Hassan, Jnah 01/830000 Trad Hospital & Medical Center Clemenceau, Mexic St. 01/369494-5 Hopital St. Joseph Dora, St. Joseph St. 01/248750 - 01/240111 Hopital Haddad Des Soeurs Du Rosaire Gemmayze, Pasteur St. 01/440800 Rassoul Al Aazam Hospital Ghoubeiry, Airport Road, in Front of Atm Station 01/452700 Sahel General Hospital Ghoubeiry, Airport Road 01/858333-4-5 - 01/840142 Hospital Fouad Khoury & Associate Hamra, Abed El Aziz St. -

World Bank Document

E- 313 VOL. 1 LEBANESE REPUBLIC COUNCILFOR DEVELOPMENTAND RECONSTRUCTION Public Disclosure Authorized BEIRUT URBAN TRANSPORT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized ENVI ONMENTAL ASSESS MENT we _--A I ->L a Public Disclosure Authorized Executive Summary May 2000 Public Disclosure Authorized pJji|team INTERNATIONAL l__|_engineering & management consultants www.team-international .com The Beirut Urban Transport Project (BUTP) PreparatoryStudy has been carried out for the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR) by the consultingfirm TEAM Intemational, and has been financed by the LebaneseGovernment. TEAMlntemational u il www.tearn-inteniational.com P.O.B 14-5303.Beirut-Lebanon Tel: 961-1-840227- Fax: 961-1-826593 LEBANESE REPUBLIC COUNCILFOR DEVELOPMENTAND RECONSTRUCTION BEIRUT URBAN TRANSPORT PROJECT EN mSESMN rr. MM200 t ea m I NTERN AT ION AIL engineering & management consultants www.teamr-international.corn BEIRUTURBAN TRANSPORT PROJECT - PREPARATORYSTUDY EAEXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..... ......................... .................... i LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS................................................. i INTRODUCTION......... ..... .... .. .. ....... EA OBJECTIVES .2 EA SCOPEOF WORK .2 EA PROCEDURESAND GUIDELINES .2 PROPOSED PROJECT COMPONENTS .3 POLICIES, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK ............................................... 7 TRANSPORTSECTOR RELATED POLICIES .7 POTENTIAL IMPACTS. ................... ,,... .................................. 10 ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVES. .. ............ -

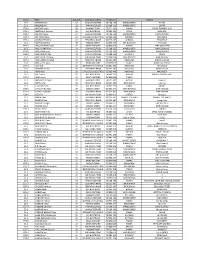

Circuit 5 Septembre 2018 (3S DB

Classe Nom Aut_AM Nom du Chauffeur Téléphone Adresse 1S‐2 ABBOUD Fadi 31 HANNA GEORGES 03/108 163 MANSOURIEH BLATA 2S‐1 ABBOUD Joe 31 HANNA GEORGES 03/108 163 MANSOURIEH BLATA EB5‐5 ABBOUD Justin 28 HASBANY TONY 76/721 402 FANAR EGLISE EVANGELIQUE EB5‐6 ABDELJALIL Richard 30 AKL BOUTROUS 76/583 322 ZALKA JAWHARJI EB6‐2 ABI‐AAD Maya 31 HANNA GEORGES 03/108 163 MANSOURIEH DAYCHOUNIEH EB5‐4 ABI‐HABIB Alexi 03 GHOUSSOUB BOUTROS 03/686 440 ROUMIEH MAR ABDA EB4‐1 ABI‐RACHED Chris 01 TEBCHRANI NAJIB 03/225 487 AYROUN PRINCIPALE 2S‐2 ABI‐RACHED Elie 39 KNOUZI SAMIR 03/596 277 JISR EL BACHA Principale EB5‐1 ABOU‐CHACRA Lucas 22 OKIAN ANTOINE 03/830 049 FANAR PERE OSSAYRAN 1S‐2 ABOU‐HANNA Joy 31 HANNA GEORGES 03/108 163 MANSOURIEH Amine Gemayel EB4‐5 ABOU‐ISSA Jane 31 HANNA GEORGES 03/108 163 MANSOURIEH MANSOURIEH EB6‐5 ABOU‐MERHI Elie 31 HANNA GEORGES 03/108 163 NAAMEH KSARA 1S‐1 ABOU‐RIZK Phillippe 17 ABI HANNA FOAD 71/906 016 MAR ROUKOZ MAR ROUKOZ EB7‐4 ABOU‐RJEILY Charbel 01 TEBCHRANI NAJIB 03/225 487 AIN SAADE MONT LA SALLE 1S‐2 ABOU‐ZEID Jana 22 OKIAN ANTOINE 03/830 049 Sodeco Mohamad El Hout EB7‐2 ACHI Jad 20 BEYROUTHEH CAMILLE 03/491 296 AIN SAADE AIN SAADE 1S‐1 ACHKAR Jérémy 01 TEBCHRANI NAJIB 03/225 487 Broumana Emile Lahoud 2S‐2 AKIKI Nour 03 GHOUSSOUB BOUTROS 03/686 440 AIN SAADE MKHAIBER 2S‐1 AKL Corine 30 AKL BOUTROUS 76/583 322 BSALIM HOPITAL MIDDLE EAST EB7‐4 AMIL Caren 22 OKIAN ANTOINE 03/830 049 FANAR 2S‐2 ANDRAOS Georges 28 HASBANY TONY 76/721 402 Antelias Fawwar 1S‐2 ANTAKI Karl 01 TEBCHRANI NAJIB 03/225 487 BROUMANA CHarkié -

Corporate Urbanization: Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Sharp, Deen Shariff Doctoral Thesis — Published Version Corporate Urbanization: Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon Provided in Cooperation with: The Bichler & Nitzan Archives Suggested Citation: Sharp, Deen Shariff (2018) : Corporate Urbanization: Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon, Graduate Faculty in Earth and Environmental Sciences, City University of New York, New York, NY, http://bnarchives.yorku.ca/593/ This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/195088 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon C o r p o r a t e U r b a n i z a t i o n By Deen Shariff Sharp, 2018 i City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Graduate Center 9-2018 Corporate Urbanization: Between the Future and Survival in Lebanon Deen S. -

Information Note

6th Mediterranean Forest Week and 23 rd session of Silva Mediterranea 1-5 April 2019, Brummana, Lebanon Information Note I. BAKGROUND The Mediterranean Forest Week (MFW) brings together a diverse set of actors to participate in one of the most vital fora on Mediterranean forests today. The biennial event facilitates cooperation amongst the research community, policy-makers and other relevant stakeholders by providing a common regional platform for dialogue. The event also promotes the relevance of Mediterranean forests globally and calls attention to the specific challenges these forests face. Participants include forest administrators, the scientific and academic community, the private sector, donors, civil society, environmental agencies and nongovernmental organizations. The last MFW in March 2017 in Agadir, Morocco, brought together more than 280 participants on the topic of forest and landscape restoration in the Mediterranean. After the MFW of 2010 in Antalya, 2011 in Avignon, 2013 in Tlemcen, 2015 in Barcelona and 2017 in Agadir, the 6th MFW will be hosted by Lebanon on 1-5 April 2019. The 6th MFW will focus on the role of Mediterranean forests in the Paris Agreement, addressing challenges and opportunities. The main objective of the 6th MFW will be to show how Mediterranean forests are important to address climate change and implement the Paris Agreement. The specific objectives of the 6th MFW are the following: 1. How Mediterranean forests contribute to global commitments related to climate change? 2. How important Mediterranean forests are for adaptation of people to climate change? 3. How important Mediterranean forests are for the adaptation of water, agriculture, cities and other sectors to climate change? 4. -

University Scholarship Program (USP III) Cooperative Agreement Number AID-268-12-00002

Lebanese American University University Scholarship Program (USP III) Cooperative Agreement Number AID-268-12-00002 SEMI-ANNUAL PROGRESS REPORT REPORTING PERIOD: April 2016 – September 2016 SUBMITTED TO: UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT (USAID) Table of Contents University Scholarship Program (USP III) .................................................................................................... 1 Cooperative Agreement Number AID-268-12-00002 .................................................................................. 1 I. Impact Summary as of September 2016 ............................................................................................... 3 II. Project Summary ................................................................................................................................... 4 III. Detailed Progress: ............................................................................................................................ 5 A. Advising and Registration: ............................................................................................................... 5 B. Monitoring of Scholars: ................................................................................................................... 5 a. OCE: ............................................................................................................................................. 5 b. Student mentors: ........................................................................................................................ -

Frequency Abroad 1 Abroad 1 Abu-Dhabi, UAE 3 Abu Dhabi

1.2 Where do your parents live? Frequency Valid abroad 1 Abroad 1 Abu-Dhabi, UAE 3 Abu Dhabi , United Arab Emirates 1 Abu Dhabi, U.A.E. 1 Abu Dhabi, UAE 4 Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates 1 Abu Dhabi,UAE 1 Abudhabi, UAE 1 al koura/ lebanon 1 Aleppo, Syria 2 Amman-Jordan 1 Amman - Jordan 1 amman, jordan 1 Amman, Jordan 7 Baabdat, Lebanon 1 Baaklien el shouf, Lebanon 1 bakaata chouf lebanon 1 barouk,lebanon 1 Beirut 1 Beirut, Ain Mreisseh, Lebanon 1 Beirut, tariek al jadiedah 1 beirut,ashrafieh,lebanon 1 Bekaa, Lebanon 1 Chebanieh, Lebanon 1 Choeifat 1 Cornet Chahwan 1 damascus, syria 1 Damascus, Syria 3 Dbaye, Lebanon 1 dead 1 Dhahran, Saudi Arabia 2 Doha - Qatar 1 Douier,Nabteyeh,Lebanon 1 Dubai, UAE 4 Dubai, United Arab Emirates 1 ghazieh, lebanon 1 Hadath, Lebanon 1 Hims, Syria 1 irbid, jordan 1 Jeddah ,KSA 1 jeddah, saudi arabia 2 Jeddah, Saudi Arabia 2 Jordan 2 Kefraya, west bekaa, lebanon 1 Khartum, Sudan 1 Khobar, KSA 1 khobar, saudi arabia 1 Khobar, Saudi Arabia 2 kuwait 1 lebanon, tripoli 1 lebanon/bekaa/kab elias 1 live with parents 1 marjeyoun, south lebanon 1 nabatieh 1 Neighborhood 2 Nicosia, Cyprus 1 North Lebanon 1 North Lebanon/ kadaa' Batroun 1 null 522 on campus as well 1 Palestine and Qatar 1 Quaroun/West Bekaa/Bekaa/Lebanon 1 Ras Maska, Koura, North of Lebanon 1 Riyadh, KSA 1 Riyadh, Saudi Arabia 5 Riyadh,KSA 1 Riyadh,Saudi Arabia 1 Riyadh. Saudi Arabia 1 rymelieh, lebanon 1 saida- Lebanon 1 Saida- Lebanon 1 saida 1 Saida 2 saida, lebanon 1 Saida, Lebanon 3 saida,lebanon 1 Salwa, Kuwait 1 Sarafand, South Lebanon 1 Saudi -

Lebanon's Legacy of Political Violence

LEBANON Lebanon’s Legacy of Political Violence A Mapping of Serious Violations of International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law in Lebanon, 1975–2008 September 2013 International Center Lebanon’s Legacy of Political Violence for Transitional Justice Acknowledgments The Lebanon Mapping Team comprised Lynn Maalouf, senior researcher at the Memory Interdisciplinary Research Unit of the Center for the Study of the Modern Arab World (CEMAM); Luc Coté, expert on mapping projects and fact-finding commissions; Théo Boudruche, international human rights and humanitarian law consultant; and researchers Wajih Abi Azar, Hassan Abbas, Samar Abou Zeid, Nassib Khoury, Romy Nasr, and Tarek Zeineddine. The team would like to thank the committee members who reviewed the report on behalf of the university: Christophe Varin, CEMAM director, who led the process of setting up and coordinating the committee’s work; Annie Tabet, professor of sociology; Carla Eddé, head of the history and international relations department; Liliane Kfoury, head of UIR; and Marie-Claude Najm, professor of law and political science. The team extends its special thanks to Dima de Clerck, who generously shared the results of her fieldwork from her PhD thesis, “Mémoires en conflit dans le Liban d’après-guerre: le cas des druzes et des chrétiens du Sud du Mont-Liban.” The team further owes its warm gratitude to the ICTJ Beirut office team, particularly Carmen Abou Hassoun Jaoudé, Head of the Lebanon Program. ICTJ thanks the European Union for their support which made this project possible. International Center for Transitional Justice The International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) works to redress and prevent the most severe violations of human rights by confronting legacies of mass abuse. -

Fallow Fields, Famine and the Making of Lebanon

FALLOW FIELDS FAMINE AND THE MAKING OF LEBANON A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Graham A. Pitts, M.A. Washington, DC June 3, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Graham A. Pitts All Rights Reserved ii FALLOW FIELDS: FAMINE AND THE MAKING OF LEBANON Graham A. Pitts, M.A. Thesis Advisor: John R. McNeill, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation narrates Lebanon’s environmental history through the lens of the country’s World War I famine. My analysis uses the catastrophe as a prism through which to reconstruct Lebanese agrarian life. Between 1887 and 1914, as many as 150,000 Lebanese migrated to the Americas. On the war’s eve, remittances from abroad formed the largest source of income for the Lebanese, followed by the export of silk. Wartime conditions made both sources of income all but impossible to obtain and the ensuing famine exposed the vulnerabilities of Lebanon’s reliance on global flows of humans and capital. One in three Lebanese perished during the war. Years of demographic instability became a crisis of excess mortality once the war denied the population access to its livelihood and the safety valve of migration. By taking the human relationship with the rest of nature as its unit of analysis, my study posits broad continuities between the late Ottoman period and the French Mandate era whereas most studies have seen World War I, and the subsequent imposition of French colonialism, as a decisive rupture.