A History of First Nations in the Fraser River Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

Francophone Historical Context Framework PDF

Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Canot du nord on the Fraser River. (www.dchp.ca); Fort Victoria c.1860. (City of Victoria); Fort St. James National Historic Site. (pc.gc.ca); Troupe de danse traditionnelle Les Cornouillers. (www. ffcb.ca) September 2019 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework Table of Contents Historical Context Thematic Framework . 3 Theme 1: Early Francophone Presence in British Columbia 7 Theme 2: Francophone Communities in B.C. 14 Theme 3: Contributing to B.C.’s Economy . 21 Theme 4: Francophones and Governance in B.C. 29 Theme 5: Francophone History, Language and Community 36 Theme 6: Embracing Francophone Culture . 43 In Closing . 49 Sources . 50 2 Francophone Historic Places Historical Context Thematic Framework - cb.com) - Simon Fraser et ses Voya ses et Fraser Simon (tourisme geurs. Historical contexts: Francophone Historic Places • Identify and explain the major themes, factors and processes Historical Context Thematic Framework that have influenced the history of an area, community or Introduction culture British Columbia is home to the fourth largest Francophone community • Provide a framework to in Canada, with approximately 70,000 Francophones with French as investigate and identify historic their first language. This includes places of origin such as France, places Québec, many African countries, Belgium, Switzerland, and many others, along with 300,000 Francophiles for whom French is not their 1 first language. The Francophone community of B.C. is culturally diverse and is more or less evenly spread across the province. Both Francophone and French immersion school programs are extremely popular, yet another indicator of the vitality of the language and culture on the Canadian 2 West Coast. -

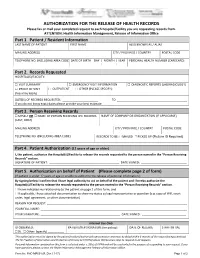

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867”

Canada 150 Lecture Series - “The Okanagan Valley to 1867” The format would include a 45 minute talk on the subject with Power Point illustrations, followed by a 15 minute question and answer period. Sunday, November 19, 1:30 pm - The First Nations – First of all, I will outline the geographical setting and then examine the culture of the Plateau Native People both pre-horse and post-horse, with particular attention to the Okanagans. The lecture will look at the subsistence culture of the Plateau First Nations, both the Salish and Sahaptan language groups and the changes that the coming of the horse brought about. I will look at their annual cycle, material culture and inter-tribal trade routes with a focus on the Okanagan Valley trail that connected the Columbia and Fraser River drainage systems. Saturday, November 25, 1:30 pm - The Fur Traders from 1811 to 1847– Beginning with the first contact with white traders such as David Thompson of the North West Company and David Stuart of the Pacific Fur Company, I will look at the routes followed and the trading posts established, particularly in the Okanagan Valley and its vicinity. The brigade trail, which ran through the Okanagan Valley from Fort Okanagan to Fort Kamloops and beyond, was the major transportation route in the Interior. I will also examine the relationship between the traders and the First Nations and the inevitable tensions of this “clash of cultures.” Sunday, December 3, 1:30 pm - The Miners’ Brigades and the Traders from 1858 to 1866 – Beginning in early 1858, there was a rush of miners to the Lower Fraser River, mostly though Victoria and Fort Langley. -

Part-Time Instructor Dakelh (Carrier)

Part-Time Instructor Posting #FAPT01-21 Dakelh (Carrier) Language Instructor First Nations Studies Faculty of Indigenous Studies, Social Sciences and Humanities The University of Northern British Columbia invites applications for an instructor in the Department of First Nations Studies to teach a single introductory Dakelh (Carrier) Language Course during the 2021 Spring Semester. This course will be taught online and is scheduled to run from 31 May 2021 to 18 June 2021 from 9:00 am to 11:50 am with an exam to be scheduled between 21-25 June 2021. Interested applicants must be willing to teach online, have experience teaching in a post-secondary and/or adult education setting, and possess a working knowledge of Dakelh. About the University and its Community Located in the spectacular landscape of northern British Columbia, UNBC is one of Canada’s best small research-intensive universities, with a core campus in Prince George and three regional campuses in Northern BC (Quesnel, Fort St. John and Terrace). We have a passion for teaching, discovery, people, the environment, and the North. Our region is comprised of friendly communities, offering a wide range of outdoor activities including exceptional skiing, canoeing and kayaking, fly fishing, hiking, and mountain biking. The lakes, forests and mountains of northern and central British Columbia offer an unparalleled natural environment in which to live and work. To Apply Applicants should forward their cover letter and curriculum vitae to the Chair of First Nations Studies, Dr. Daniel Sims, at [email protected] by 30 April 2021. All qualified candidates are encouraged to apply; however, Canadians and permanent residents will be given priority. -

Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study On

Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study on the Enbridge Gateway Pipeline An Assessment of the Impacts of the Proposed Enbridge Gateway Pipeline on the Carrier Sekani First Nations May 2006 Carrier Sekani Tribal Council i Aboriginal Interests & Use Study on the Proposed Gateway Pipeline ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Carrier Sekani Tribal Council Aboriginal Interests & Use Study was carried out under the direction of, and by many members of the Carrier Sekani First Nations. This work was possible because of the many people who have over the years established the written records of the history, territories, and governance of the Carrier Sekani. Without this foundation, this study would have been difficult if not impossible. This study involved many community members in various capacities including: Community Coordinators/Liaisons Ryan Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Bev Ketlo, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Sara Sam, Nak’azdli First Nation Rosa McIntosh, Saik’uz First Nation Bev Bird & Ron Winser, Tl’azt’en Nation Michael Teegee & Terry Teegee, Takla Lake First Nation Viola Turner, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Elders, Trapline & Keyoh Holders Interviewed Dick A’huille, Nak’azdli First Nation Moise and Mary Antwoine, Saik’uz First Nation George George, Sr. Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Rita George, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Patrick Isaac, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Peter John, Burns Lake Band Alma Larson, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Betsy and Carl Leon, Nak’azdli First Nation Bernadette McQuarry, Nadleh Whut’en First Nation Aileen Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Donald Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Guy Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Vince Prince, Nak’azdli First Nation Kenny Sam, Burns Lake Band Lillian Sam, Nak’azdli First Nation Ruth Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Ryan Tibbetts, Burns Lake Band Joseph Tom, Wet’suwet’en First Nation Translation services provided by Lillian Morris, Wet’suwet’en First Nation. -

Language Data Tables User Guide

Demolinguistic Data for Indigenous Communities in Canada Language Data Tables User Guide Version 0.7.1 Norris Research Inc. https://norrisresearch.com/ref_tables.htm 1 January 2021 Norris Research: Language Data Tables Users Guide DRAFT January 1, 2021 Recommended Citation: Norris Research Inc. (2020). Demolinguistic Data for Indigenous communities in Canada: Language Data Tables Users Guide, 01 January 2021. Draft Report prepared under contract with the Department of Canadian Heritage. Norris Research: Language Data Tables Users Guide DRAFT January 1, 2021 Table of Contents Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 !! IMPORTANT !! ..................................................................................................................................................................... 9 A Cautionary Note ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 Website Tips and Tricks ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Tables ................................................................................................................................................................................ 11 Tree View ......................................................................................................................................................................... -

Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan 1

Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan 1 BURNS LAKE RURAL AND FRANCOIS LAKE (NORTH SHORE) OFFICIAL COMMUNITY PLAN BYLAW No. 1785, 2017 Schedule “A” Regional District of Bulkley-Nechako PLANNING DEPARTMENT RD 37 – 3 AVENUE PHONE (250) 692-3195 P.O. BOX 820 TOLL-FREE (800) 320-3339 BURNS LAKE, BRITISH COLUMBIA FAX (250) 692-1220 V0J 1E0 EMAIL: [email protected] RDBN Bylaw No. 1785, 2016 Section 1: Introduction January 12, 2017 2 Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan Please note that this document (Schedule “A”) is one of three parts of the Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan. This Plan also includes the Land Use Designation Map (Schedule “B”) and the Ecological and Wildlife Values Map (Schedule “C”) to which this document refers. Both maps can be viewed at the Regional District office. If you wish to obtain a copy of either map, large format copying charges apply. The maps are also available on the Regional District’s website: www.rdbn.bc.ca. Section 1: Introduction RDBN Bylaw No. 1785, 2017 LIST OF OCP AMENDMENTS Area B, E Commencing 2018 LIST OF OCP AMENDMENTS # BYLAW NO ADOPTION DATE CONTENT FOLIO NO. 1 1834 June 21, 2018 Designation changed from 755/10391.100 RE to RR 2 1913 September 17, 2020 Designation changed from 755/10382.000 “Resource (RE)” to “Rural Residential (RR)” Burns Lake Rural and Francois Lake (North Shore) Official Community Plan 3 Table of Contents SECTION 1 – INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 4 1.1 Purpose ................................................................................................. -

An Anatomy of Carrier Cremation Cruelty in the Historical Record1

“Caledonian Suttee”? An Anatomy of Carrier Cremation 1 Cruelty in the Historical Record I.S. MACL AREN etween 1820 and 1860 four published stories about Native barbarity contributed to the demonization of the inhabitants of the Pacific Slope inland from coastal areas. The first was B 1812 the record of a Carrier cremation in January at Stuart Lake; the second was an incident of Iroquois cannibalism in May 1817 on the upper Columbia River; the third was the murder by a vengeful Shuswap of Hudson’s Bay Company chief factor Samuel Black at Thompson River Fort on 8 February 1841; and the fourth was the massacre by Caiuse of the Whitmans at Waillatpu in November 1847.2 These stories came to form readers’ perceptions of the barbarians of the Interior, and became instances of what has been called occupational folklore.3 Of these, Carrier cremation cruelty alone involved only Native people. It was “the subject of much jaundiced comment by Europeans,” whose 1 An earlier version of this essay was read before the British Columbia Inside/Out Conference organized by BC Studies and the BC Political Studies Association, University of Northern British Columbia, 28-30 April 2005. I wish to thank Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy for generously permitting me access to their extensive library, which brought to my attention many sources cited herein. 2 The first published appearances of each of the four occurred in Daniel Williams Harmon, A Journal of Voyages and Travels in the Interiour of North America, ed. Rev. Daniel Haskel (Andover, VT: Flagg and Gould, 1820), 215-18; Ross Cox, Adventures on the Columbia River, 2 vols. -

Lhtako Dene First Nation

northern health the northern way of caring ABORIGINAL RESOURCE GUIDE 2019 Artwork on cover by Artist Curtis Boyd northern health TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................... 4 Ndazkoh First Nation ......................................... 6 Dene First Nation............................................. 10 ?Esdilagh First Nation ..................................... 14 Lhoosk’uz Dene First Nation ........................... 18 Additional Resources ....................................... 21 Medicine Wheel ............................................... 29 Quesnel Health Services Contact Numbers ..... 31 Southern Carrier Terminology ......................... 32 Hospital Terminology ...................................... 34 Footprints in Stone.......................................... 37 Contacts .......................................................... 48 ABORIGINAL 2 RESOURCE GUIDE 3 northern health INTRODUCTION Quesnel Health Services provides services to four local bands: Ndazkoh First Nations (Nazko), Lhoosk’uz Dene Nation (Kluskus), ?Esdilagh First Nation (Alexandria) and Lhtako Dene Nation (Red Bluff), as well as to the urban population of local First Nation, Inuit and Metis people. This Guide will provide information on our local First Nations, community resources, culture and history. A Quick Overview Nazko, Kluskus and Red Bluff are all Southern Carrier Nations. Their traditional language is Carrier, which is part of the northern Athabaskan language family which is spoken throughout Northern -

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon

The Archaeology of 1858 in the Fraser Canyon Brian Pegg* Introduction ritish Columbia was created as a political entity because of the events of 1858, when the entry of large numbers of prospectors during the Fraser River gold rush led to a short but vicious war Bwith the Nlaka’pamux inhabitants of the Fraser Canyon. Due to this large influx of outsiders, most of whom were American, the British Parliament acted to establish the mainland colony of British Columbia on 2 August 1858.1 The cultural landscape of the Fraser Canyon underwent extremely significant changes between 1858 and the end of the nineteenth century. Construction of the Cariboo Wagon Road and the Canadian Pacific Railway, the establishment of non-Indigenous communities at Boston Bar and North Bend, and the creation of the reserve system took place in the Fraser Canyon where, prior to 1858, Nlaka’pamux people held largely undisputed military, economic, legal, and political power. Before 1858, the most significant relationship Nlaka’pamux people had with outsiders was with the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), which had forts at Kamloops, Langley, Hope, and Yale.2 Figure 1 shows critical locations for the events of 1858 and immediately afterwards. In 1858, most of the miners were American, with many having a military or paramilitary background, and they quickly entered into hostilities with the Nlaka’pamux. The Fraser Canyon War initially conformed to the pattern of many other “Indian Wars” within the expanding United States (including those in California, from whence many of the Fraser Canyon miners hailed), with miners approaching Indigenous inhabitants * The many individuals who have contributed to this work are too numerous to list. -

Typotheque North American Syllabics Proposed Revisions to The

Typotheque Prepared by Kevin King Typotheque [email protected] www.typotheque.com 04/06/21 North American Syllabics Proposed revisions to the representative characters of the Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics code charts Typotheque Proposed representative character revisions of the Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics 2 CONTENTS 1 Summary of proposed character revisions 3 2 Revisions for Carrier 9 3 Revisions for Sayisi 36 4 Revisions for Ojibway 46 Bibliography 52 Acknowledgements 54 Typotheque Proposed representative character revisions of the Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics 3 1 Summary of proposed character revisions The following proposal requests 120 revisions to the representative char- acters in the official code charts of Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics main and extended blocks. The proposed characters for revision have been summarized below with representative glyphs and corresponding character names with annotations where applicable. Additionally, revised code charts for UCAS main and extended has been provided in the following section with the proposed revised representative characters marked in pink, imple- mented into their corresponding code point locations. The author has prepared a style-matched font for the purpose of imple- menting into the code chart: 144B ᑋ CANADIAN SYLLABICS carrier H 160D ᘍ CANADIAN SYLLABICS carrier ma 14D1 ᓑ CANADIAN SYLLABICS carrier NG 160E ᘎ CANADIAN SYLLABICS carrier yu 1506 ᔆ CANADIAN SYLLABICS athapascan s 160F ᘏ CANADIAN SYLLABICS carrier yO 15C0 ᗀ CANADIAN SYLLABICS Sayisi