UNDERSTANDING PSYCHOSIS Resources and Recovery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

Clinically Significant Avoidance of Public

Journal of Anxiety Disorders 23 (2009) 1170–1176 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Anxiety Disorders Clinically significant avoidance of public transport following the London bombings: Travel phobia or subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder? Rachel V. Handley a,*, Paul M. Salkovskis a, Peter Scragg b, Anke Ehlers a a King’s College London, Institute of Psychiatry, Department of Psychology, and Centre for Anxiety Disorders and Trauma, London, UK b Trauma Clinic, London, UK ARTICLEI NFO ABSTRA CT Article history: Following the London bombings of 7 July 2005 a ‘‘screen and treat’’ program was set up with the aim of Received 6 March 2008 providing rapid treatment for psychological responses in individuals directly affected. The present study Received in revised form 28 July 2009 found that 45% of the 596 respondents to the screening program reported phobic fear of public transport Accepted 28 July 2009 in a screening questionnaire. The screening program identified 255 bombing survivors who needed treatment for a psychological disorder. Of these, 20 (8%) suffered from clinically significant travel phobia. Keywords: However, many of these individuals also reported symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]. Terrorist violence Comparisons between the travel phobia group and a sex-matched group of bombing survivors with PTSD Specific phobia showed that the travel phobic group reported fewer re-experiencing and arousal symptoms on the Posttraumatic stress disorder Screening Trauma Screening Questionnaire (Brewin et al., 2002). The only PTSD symptoms that differentiated the groups were anger problems and feeling upset by reminders of the bombings. There was no difference between the groups in the reported severity of trauma or in presence of daily transport difficulties. -

Neuropsychiatric Masquerades: Is It a Horse Or a Zebra NCPA Annual Conference Winston-Salem, NC October 3, 2015

Neuropsychiatric Masquerades: Is it a Horse or a Zebra NCPA Annual Conference Winston-Salem, NC October 3, 2015 Manish A. Fozdar, M.D. Triangle Forensic Neuropsychiatry, PLLC, Raleigh, NC www.BrainInjuryExpert.com Consulting Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry, Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine Disclosures • Neither I nor any member of my immediate family has a financial relationship or interest with any proprietary entity producing health care goods or services related to the content of this CME activity. • I am a non-conformist and a cynic of current medical establishment. • I am a polar opposite of being PC. No offense intended if one taken by you. Anatomy of the talk • Common types of diagnostic errors • Few case examples • Discussion of selected neuropsychiatric masquerades When you hear the hoof beats, think horses, not zebras • Most mental symptoms are caused by traditional psychiatric syndromes. • Majority of patients with medical and neurological problems will not develop psychiatric symptoms. Case • 20 y/o AA female with h/o Bipolar disorder and several psych hospitalizations. • Admitted a local psych hospital due to decompensation.. • While at psych hospital, she develops increasing confusion and ataxia. • Transferred to general med-surg hospital. • Stayed for 2 weeks. • Here is what happened…. • Psych C-L service consulted. We did the consult and followed her throughout the hospital stay. • Initial work up showed Normal MRI, but was of poor quality. EEG was normal. • She remained on the hospitalist service. 8 different hospitalists took care of her during her stay here. • Her presentation was chalked off to “her psych disorder”, “Neuroleptic Malignant syndrome” etc. -

Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide

SPANISH CLINICAL LANGUAGE AND RESOURCE GUIDE The Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide has been created to enhance public access to information about mental health services and other human service resources available to Spanish-speaking residents of Hennepin County and the Twin Cities metro area. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information, we make no guarantees. The inclusion of an organization or service does not imply an endorsement of the organization or service, nor does exclusion imply disapproval. Under no circumstances shall Washburn Center for Children or its employees be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential damages which may result in any way from your use of the information included in the Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide. Acknowledgements February 2015 In 2012, Washburn Center for Children, Kente Circle, and Centro collaborated on a grant proposal to obtain funding from the Hennepin County Children’s Mental Health Collaborative to help the agencies improve cultural competence in services to various client populations, including Spanish-speaking families. These funds allowed Washburn Center’s existing Spanish-speaking Provider Group to build connections with over 60 bilingual, culturally responsive mental health providers from numerous Twin Cities mental health agencies and private practices. This expanded group, called the Hennepin County Spanish-speaking Provider Consortium, meets six times a year for population-specific trainings, clinical and language peer consultation, and resource sharing. Under the grant, Washburn Center’s Spanish-speaking Provider Group agreed to compile a clinical language guide, meant to capture and expand on our group’s “¿Cómo se dice…?” conversations. -

Specificity of Psychosis, Mania and Major Depression in A

Molecular Psychiatry (2014) 19, 209–213 & 2014 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/14 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Specificity of psychosis, mania and major depression in a contemporary family study CL Vandeleur1, KR Merikangas2, M-PF Strippoli1, E Castelao1 and M Preisig1 There has been increasing attention to the subgroups of mood disorders and their boundaries with other mental disorders, particularly psychoses. The goals of the present paper were (1) to assess the familial aggregation and co-aggregation patterns of the full spectrum of mood disorders (that is, bipolar, schizoaffective (SAF), major depression) based on contemporary diagnostic criteria; and (2) to evaluate the familial specificity of the major subgroups of mood disorders, including psychotic, manic and major depressive episodes (MDEs). The sample included 293 patients with a lifetime diagnosis of SAF disorder, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder (MDD), 110 orthopedic controls, and 1734 adult first-degree relatives. The diagnostic assignment was based on all available information, including direct diagnostic interviews, family history reports and medical records. Our findings revealed specificity of the familial aggregation of psychosis (odds ratio (OR) ¼ 2.9, confidence interval (CI): 1.1–7.7), mania (OR ¼ 6.4, CI: 2.2–18.7) and MDEs (OR ¼ 2.0, CI: 1.5–2.7) but not hypomania (OR ¼ 1.3, CI: 0.5–3.6). There was no evidence for cross-transmission of mania and MDEs (OR ¼ .7, CI:.5–1.1), psychosis and mania (OR ¼ 1.0, CI:.4–2.7) or psychosis and MDEs (OR ¼ 1.0, CI:.7–1.4). -

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Eating Disorders: About More Than Food Has your urge to eat less or more food spiraled out of control? Are you overly concerned about your outward appearance? If so, you may have an eating disorder. National Institute of Mental Health What are eating disorders? Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses marked by severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may be signs of an eating disorder. These disorders can affect a person’s physical and mental health; in some cases, they can be life-threatening. But eating disorders can be treated. Learning more about them can help you spot the warning signs and seek treatment early. Remember: Eating disorders are not a lifestyle choice. They are biologically-influenced medical illnesses. Who is at risk for eating disorders? Eating disorders can affect people of all ages, racial/ethnic backgrounds, body weights, and genders. Although eating disorders often appear during the teen years or young adulthood, they may also develop during childhood or later in life (40 years and older). Remember: People with eating disorders may appear healthy, yet be extremely ill. The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and social factors can raise a person’s risk. What are the common types of eating disorders? Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. If you or someone you know experiences the symptoms listed below, it could be a sign of an eating disorder—call a health provider right away for help. -

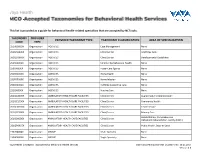

This List Is Provided As a Guide for Behavioral Health-Related Specialties That Are Accepted by Nctracks

This list is provided as a guide for behavioral health-related specialties that are accepted by NCTracks. TAXONOMY PROVIDER PROVIDER TAXONOMY TYPE TAXONOMY CLASSIFICATION AREA OF SPECIALIZATION CODE TYPE 251B00000X Organization AGENCIES Case Management None 261QA0600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Adult Day Care 261QD1600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Developmental Disabilities 251S00000X Organization AGENCIES Community/Behavioral Health None 253J00000X Organization AGENCIES Foster Care Agency None 251E00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Health None 251F00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Infusion None 253Z00000X Organization AGENCIES In-Home Supportive Care None 251J00000X Organization AGENCIES Nursing Care None 261QA3000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Augmentative Communication 261QC1500X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Community Health 261QH0100X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Health Service 261QP2300X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Primary Care Rehabilitation, Comprehensive 261Q00000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF) 261QP0905X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Public Health, State or Local 193200000X Organization GROUP Multi-Specialty None 193400000X Organization GROUP Single-Specialty None Vaya Health | Accepted Taxonomies for Behavioral Health Services Claims and Reimbursement | Content rev. 10.01.2017 Version -

Mental Health Disorders: Strategies for Approach & Treatment

3/20/2019 Mental Health Disorders: Strategies for Approach & Treatment Transform 2019: OPTA Annual Conference Columbus, Ohio April 6th, 2019 Dawn Bookshar, PT, DPT, GCS Ian Kilbride, PT Marcia Zeiger, OTRL Objectives Participants will: • Understand the prevalence and impact of mental health disorders in client populations • Understand clinical conditions, and associated characteristics of common mental health diagnoses • Apply effective treatment approaches for clients with mental illness. • Produce effective clinical documentation to support intervention for clients with mental illness Mental Illness (MI) www.schizophrenia.com 1 3/20/2019 Mental Illness (MI) The term mental illness refers collectively to all diagnosable mental disorders defined as sustained abnormal alterations in thinking, mood, or behavior associated with distress and impaired functioning which substantially interferes with or limits one or more major life activities. National Institute of Mental Health Prevalence of MI • More than 50% will be diagnosed with a mental illness or disorder at some point in their lifetime. • 1 in 5 Americans will experience a mental illness in a given year. • 1 in 25 Americans lives with a serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention Prevalence of MI in LTC • 2/3 of people in nursing homes have a mental illness. • Nursing home residents with a primary diagnosis of mental illness range from 18.7% among those aged 65-74 years to 23.5% among those aged 85+ years. • Dementia, Alzheimer disease, and mood disorders are the most common diagnoses of mental illness in long-term care settings. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention 2 3/20/2019 Prevalence of MI in LTC Ohio • Residents with a diagnosis of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder increased from 9% to 16% between 2001 to 2016. -

Eating Disorders

Eating Disorders NDSCS Counseling Services hopes the following information will help you gain a better understanding of eating disorders. If you believe you or someone you know is experiencing related concerns and would like to visit with a counselor, please call NDSCS Counseling Services for an appointment - 701.671.2286. Definition There is a commonly held view that eating disorders are a lifestyle choice. Eating disorders are actually serious and often fatal illnesses that cause severe disturbances to a person’s eating behaviors. Obsessions with food, body weight, and shape may also signal an eating disorder. Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder. Signs and Symptoms Anorexia nervosa People with anorexia nervosa may see themselves as overweight, even when they are dangerously underweight. People with anorexia nervosa typically weigh themselves repeatedly, severely restrict the amount of food they eat, and eat very small quantities of only certain foods. Anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate of any mental disorder. While many young women and men with this disorder die from complications associated with starvation, others die of suicide. In women, suicide is much more common in those with anorexia than with most other mental disorders. Symptoms include: • Extremely restricted eating • Extreme thinness (emaciation) • A relentless pursuit of thinness and unwillingness to maintain a normal or healthy weight • Intense fear of gaining weight • Distorted body image, a self-esteem -

Department of Veterans Affairs § 4.130

Department of Veterans Affairs § 4.130 than 50 percent and schedule an exam- upon the Diagnostic and Statistical ination within the six month period Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth following the veteran’s discharge to de- Edition, of the American Psychiatric termine whether a change in evalua- Association (DSM-IV). Rating agencies tion is warranted. must be thoroughly familiar with this (Authority: 38 U.S.C. 1155) manual to properly implement the di- rectives in § 4.125 through § 4.129 and to [61 FR 52700, Oct. 8, 1996] apply the general rating formula for § 4.130 Schedule of ratings—mental mental disorders in § 4.130. The sched- disorders. ule for rating for mental disorders is The nomenclature employed in this set forth as follows: portion of the rating schedule is based Rating Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders 9201 Schizophrenia, disorganized type 9202 Schizophrenia, catatonic type 9203 Schizophrenia, paranoid type 9204 Schizophrenia, undifferentiated type 9205 Schizophrenia, residual type; other and unspecified types 9208 Delusional disorder 9210 Psychotic disorder, not otherwise specified (atypical psychosis) 9211 Schizoaffective disorder Delirium, Dementia, and Amnestic and Other Cognitive Disorders 9300 Delirium 9301 Dementia due to infection (HIV infection, syphilis, or other systemic or intracranial infections) 9304 Dementia due to head trauma 9305 Vascular dementia 9310 Dementia of unknown etiology 9312 Dementia of the Alzheimer’s type 9326 Dementia due to other neurologic or general medical conditions (endocrine -

The Trauma of First Episode Psychosis: the Role of Cognitive Mediation

The trauma of first episode psychosis: the role of cognitive mediation Chris Jackson, Claire Knott, Amanda Skeate, Max Birchwood Objective: First episode psychosis can be a distressing and traumatic event which has been linked to comorbid symptomatology, including anxiety, depression and PTSD symp- toms (intrusions, avoidance, etc.). However, the link between events surrounding a first episode psychosis (i.e. police involve- ment, admission, use of Mental Health Act, etc.) and PTSD symptoms remains unproven. In the PTSD literature, attention has now turned to the patient’s appraisal of the traumatic event as a key mediator. In this study we aim to evaluate the diagnostic status of first episode psychosis as a PTSD-triggering event and to determine the extent to which cognitive factors such as appraisals and coping mechanisms can mediate the expression of PTSD (traumatic) symptomatology. Method: Approximately 1.5 years after their first episode of psychosis, patients were assessed for traumatic symptoms, conformity to DSM-IV criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and their appraisals of the traumatic events and coping strategies. Psychotic symptomatology was also measured. Results: 31% of the sample of 35 patients who agreed to participate reported symptoms consistent with a diagnosis of PTSD. Although no relationship was found between PTSD (traumatic) symptoms and potentially traumatic aspects of the first episode (including place of treatment, detention under the MHA etc.), intrusions and avoidance were positively related to retrospective appraisals of stressfulness of the ward (i.e. the more stressful they rated it the greater the number of PTSD symptoms) and the patient’s coping style (sealers were less likely to report intrusive re-experiencing but more likely to report avoidance).