R a C E T R a I T O R Tre a So N to W Hiteness Is Loyalty to Hum Anity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luke F. Parsons White

GO TO LIST OF PEOPLE INVOLVED IN HARPERS FERRY VARIOUS PERSONAGES INVOLVED IN THE FOMENTING OF RACE WAR (RATHER THAN CIVIL WAR) IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR Luke Fisher Parsons was a free-state fighter seasoned in “Bleeding Kansas.” He took part in the battle of Black Jack near Baldwin City on June 2d, 1856, the battle of Osawatomie on August 30th, 1856, and the raid on Iowa during Winter 1857/1858. His name “L.F. Parsons” was among the signatories to “Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States,” per a document in John Brown’s handwriting that would be captured when the raiders were subdued at Harpers Ferry. He had gone off toward a supposed Colorado gold rush and, summoned by letters from Brown and Kagi, did not manage to make it back to take part in the raid on the federal arsenal, or to attempt to rescue the prisoners once they were waiting to be hanged, at the jail in Charlestown, Virginia. He started a family and lived out a long life as a farmer in Salina, Kansas. HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR THOSE INVOLVED, ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY SECRET “SIX” Person’s Name On Raid? Shot Dead? Hanged? His Function Age Race Charles Francis Adams, Sr. No No No Finance white Charles Francis Adams, Sr. subscribed to the racist agenda of Eli Thayer’s and Amos Lawrence’s New England Emigrant Aid Company, for the creation of an Aryan Nation in the territory then well known as “Bleeding Kansas,” to the tune of $25,000. -

96 American Manuscripts

CATALOGUE TWO HUNDRED NINETY-TWO 96 American Manuscripts WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is made up or manuscripts relating to the history of the Americas from the conquistadors, with the narrative of Domingo de Irala in South America in 1555, to a manuscript of “America the Beautiful” at the end of the 19th century. Included are letters, sketchbooks, ledgers, plat maps, requisition forms, drafts of government documents, memoirs, diaries, depositions, inventories, muster rolls, lec- ture notes, completed forms, family archives, and speeches. There is a magnificent Stephen Austin letter about the Texas Revolution, a certified copy of Amendment XII to the Constitution, and a host of other interesting material. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues 282, Recent Acquisitions in Americana; 283, American Presidents; 285, The English Colonies in North America 1590- 1763; 287, Western Americana; 288, The Ordeal of the Union; 290, The American Revolution 1765-1783; and 291, The United States Navy, as well as Bulletin 21, American Cartog- raphy; Bulletin 22, Evidence; Bulletin 24, Provenance; Bulletin 25, American Broadsides, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the Internet at www.reeseco.com. A portion of our stock may be viewed via links at www. reeseco.com. If you would like to receive e-mail notification when catalogues and lists are uploaded, please e-mail us at [email protected] or send us a fax, specifying whether you would like to receive the notifications in lieu of or in addition to paper catalogues. -

The John and Mary Ritchie House (1116 SE Madison, Topeka, Shawnee County) Was Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 12/29/2015

6425 SW 6th Avenue phone: 785-272-8681 Topeka KS 66615 fax: 785-272-8682 [email protected] Sam Brownback, Governor Jennie Chinn, Executive Director The John and Mary Ritchie House (1116 SE Madison, Topeka, Shawnee County) was listed in the National Register of Historic Places 12/29/2015. The nomination was submitted to the NPS as eligible under Criterion B for its association with the Ritchies and under Criterion C for its architecture. The NPS listed the Ritchie House in the National Register under Criterion B alone, stating that the amount of alteration to the house precludes its listing also under Criterion C. January 12, 2016 Amanda Loughlin National Register Coordinator NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Listed in National Register 12/29/2015 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property Historic name Ritchie, John & Mary, House Other names/site number KHRI #177-5400-00563 Name of related Multiple Property Listing N/A 2. Location Street & number 1116 SE Madison Street not for publication City or town Topeka vicinity State Kansas Code KS County Shawnee Code 177 Zip code 66607 3. -

Gerrit Smith

GO TO LIST OF PEOPLE INVOLVED IN HARPERS FERRY VARIOUS PERSONAGES INVOLVED IN THE FOMENTING OF RACE WAR (RATHER THAN CIVIL WAR) IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR GERRIT SMITH It is clear that Henry Thoreau was not trusted with any of the secrets of the conspiracy we have come to know as the Secret “Six,” to the extent that his future editor and biographer Franklin Benjamin Sanborn confided to him nothing whatever about the ongoing meetings which he was having with the Reverend Thomas Wentworth “Charles P. Carter” Higginson, the Reverend Theodore Parker, Gerrit Smith, Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe, and George Luther Stearns. For Thoreau commented in his JOURNAL in regard to Captain John Brown, “it would seem that he had not confidence enough in me, or in anybody else that I know [my emphasis], to communicate his plans to us.” –And, Thoreau could not have believed this and could not have made such an entry in his journal had any member of the Secret Six been providing him with any clues whatever that there was something going on behind the scenes, within their own private realm of scheming! Had it been the case, that Thoreau had become aware that there was in existence another, parallel, universe of scheming, rather than writing “or in anybody else that I know,” he would most assuredly have written something more on the order of HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR (perhaps) “it would seem that they had not confidence enough in me, to provide me any insight into their plans.” Treason being punished as what it is, why would the downtown Boston lawyer Richard Henry Dana, Jr. -

How and Where to Look It Up: Resources for Researching the History of Jefferson County, West Virginia

HOW AND WHERE TO LOOK IT UP: RESOURCES FOR RESEARCHING THE HISTORY OF JEFFERSON COUNTY, WEST VIRGINIA. William D. Theriault, Ph.D. ©2001 William D. Theriault P.O. Box 173, Bakerton, WV 25431 e-mail: [email protected] Foreword This work tries to give students of Jefferson County, West Virginia, history the resources needed to confront the mass of information relevant to its past. How and Where To Look It Up contains twenty-three chapters that provide an overview of primary and secondary sources available on a broad range of topics. The accompanying Bibliography on compact disc furnishes more than 6,500 annotated citations on county history. Together they comprise the most comprehensive reference guide published on Jefferson County history to date. Despite the scope of this effort, it is incomplete. Thousands of older sources wait to be identified, perhaps by the readers of this work. New sources appear regularly, the product of more recent studies. I have temporarily suspended my information gathering efforts to publish this book and CD during Jefferson County’s bicentennial year. I hope that those inspired by the county’s 200th anniversary celebration will find it useful and will contribute to this ongoing effort. The format I have chosen for this information reflects changing tastes and technologies. A few years ago, I would have had no choice but to print all of this work on paper, a limitation that would have made the bibliography unwieldy to use and expensive to publish. Today, compact disc and Internet publication provide new ways to access old information if you have a computer. -

Albert Hazlett

GO TO LIST OF PEOPLE INVOLVED IN HARPERS FERRY VARIOUS PERSONAGES INVOLVED IN THE FOMENTING OF RACE WAR (RATHER THAN CIVIL WAR) IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR Albert Hazlett, born in Pennsylvania on September 21, 1837, did not take part in the fight at Harpers Ferry but, with John Edwin Cook who had escaped from that fight by climbing a tree and who later identified him to the prosecutors, would be belatedly hanged. Before the raid he had worked on his brother’s farm in western Pennsylvania, and he had joined the others at Kennedy Farm in the early part of September 1859. He was arrested on October 22d in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, near Chambersburg, where he was using the name “William Harrison,” was extradited to Virginia, was tried and sentenced at the spring term of the Court, and was hanged on March 16th, 1860. George B. Gill said that “I was acquainted with Hazlett well enough in Kansas, yet after all knew but little of him. He was with Montgomery considerably, and was with [Aaron D. Stevens] on the raid in which Cruise was killed. He was a good- sized, fine-looking fellow, overflowing with good nature and social feelings.... Brown got acquainted with him just before leaving “Bleeding Kansas.” To Mrs. Rebecca B. Spring he wrote on March 15th, 1860, the eve of his execution, “Your letter gave me great comfort to know that my body would be taken from this land of chains.... I am willing to die in the cause of liberty, if I had ten thousand lives I would willingly lay them all down for the same cause.” HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR THOSE INVOLVED, ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY SECRET “SIX” Person’s Name On Raid? Shot Dead? Hanged? His Function Age Race Charles Francis Adams, Sr. -

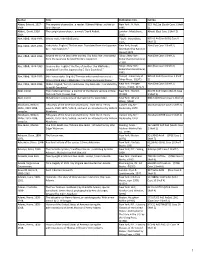

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

Lysander Spooner

HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR VARIOUS PERSONAGES INVOLVED IN THE FOMENTING OF RACE WAR (RATHER THAN CIVIL WAR) IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The anarchist (or, to deploy a more recent term, libertarian) Boston attorney Lysander Spooner, who was well aware of John Brown’s plans for the raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, wrote to Gerrit Smith during January 1859 warning that Brown had neither the men nor the resources to succeed. After the raid he would plot the kidnapping of Governor Henry A. Wise of Virginia, the idea being to take him at pistol point aboard a tug and hold him off the Atlantic coast at threat of execution should Brown be hanged. The motto he chose for himself, that might well be inscribed on his tombstone in Forest Hills Cemetery, was from the INSTITUTES of the Emperor Justinian I of the eastern Roman Empire: “To live honestly is to hurt no one, and give to every one his due.” HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR THOSE INVOLVED, ARRANGED ALPHABETICALLY SECRET “SIX” Person’s Name On Raid? Shot Dead? Hanged? His Function Age Race Charles Francis Adams, Sr. No No No Finance white Charles Francis Adams, Sr. subscribed to the racist agenda of Eli Thayer’s and Amos Lawrence’s New England Emigrant Aid Company, for the creation of an Aryan Nation in the territory then well known as “Bleeding Kansas,” to the tune of $25,000. Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson Yes Yes Captain or Lt. 26 white HDT WHAT? INDEX RACE WAR, NOT CIVIL WAR Person’s Name On Raid? Shot Dead? Hanged? His Function Age Race The maternal grandfather of Jeremiah Goldsmith Anderson, Colonel Jacob Westfall of Tygert Valley, Virginia, had been a soldier in the revolution and a slaveholder. -

William Walker

1850 ES LA MITAD DEL SIGLO XIX y en esa época Nicaragua se vislumbra como futuro centro de comunicación y comercio del mundo. Nuestra soñada Ruta del Canal resulta zona de fricción entre Estados Unidos e Inglaterra; naciente coloso el uno, que busca el tránsito por el istmo en el Sur al iniciar la conquista de su Oeste; y en su meridiano apogeo la otra, que coloniza continentes y es reina de los mares. En esa rivalidad de potencias extranjeras, con participación de intereses costarricenses, entró en juego nuestra nacionalidad, sufriendo el desmembramiento permanente del Guanacaste y el transitorio del 'Protectorado" de la Mosquitia; experimentando la repentina obstrucción de San Juan del Norte, nuestra puerta al Atlántico, cuya bahía se cegó en 1859 a causa de fuerzas naturales modificadas por el hombre; y resistiendo heroicamente la transformación radical que William Walker pretendiera imponemos con su Falange de filibusteros —desventuras todas que acaecieron, en gran parte, por encontramos divididos y exhaustos a consecuencia de las luchas fratricidas. Estudiar ese crucial capitulo de nuestro pasado (el cual se cierra con la muerte de Walker en 1860), recopilar y analizar su histonogralTa aún inédita, y presentar el fruto de tales investigaciones en volúmenes de formato legible y decoro tipográfico, es el propósito del Autor de este trabajo, quien hoy en 1994 publica este quinto tomo en español de la Biografr'a de Walker ya publicada en cinco tomos en inglés, prosiguiendo así aquella tarea iniciada en 1971. A.B. G. WILLIAM WALKER EL PREDESTINADO DE LOS OJOS GRISES BIOGRAFÍA Por ALEJANDRO BOLAÑOS GEYER TOMO V I MPRESIÓN PRIVADA St. -

![Aaron D. Stevens] on the Raid in Which Cruise Was Killed](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7472/aaron-d-stevens-on-the-raid-in-which-cruise-was-killed-12827472.webp)

Aaron D. Stevens] on the Raid in Which Cruise Was Killed

GO TO LIST OF PEOPLE INVOLVED IN HARPERS FERRY VARIOUS PERSONAGES INVOLVED IN THE FOMENTING OF RACE WAR (RATHER THAN CIVIL WAR) IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Aaron Dwight Stevens, John Brown’s drillmaster, was of old Puritan stock, his great-grandfather having served as a captain during the Revolution. He had run away from home at the age of 16 to serve with a Massachusetts volunteer regiment during the Mexican War. Well over 6 feet, he made himself proficient with the sword. Enlisted in Company F of the 1st US Dragoons, he became their bugler, but at Taos, New Mexico during 1855 he received a sentence of death for “mutiny, engaging in a drunken riot, and assaulting Major George [Alexander Hamilton] Blake.” This was commuted by President Franklin Pierce to 3 years hard labor but he escaped from Fort Leavenworth in 1856, 1st finding refuge with the Delaware tribe and then joining the Kansas Free State militia of James Lane under the name “Whipple.” He became Colonel of the 2d Kansas Militia and met Brown on August 7th, 1856 at the Nebraska line when Lane’s Army of the North marched into “Bleeding Kansas”. He became a devoted follower. He was a spiritualist. At Harpers Ferry, when Brown sent this middleaged man out along with his son Watson Brown to negotiate under a flag of truce, he received 4 bullets but was taken alive. The never-married Stevens had a relationship of sorts with Rebecca B. Spring of the Eagleswood social experiment near Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and after his execution on March 16th would be buried there alongside Albert Hazlett.