Diplomacy – Alexander Rules 1 Individually

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marvel Universe by Hasbro

Brian's Toys MARVEL Buy List Hasbro/ToyBiz Name Quantity Item Buy List Line Manufacturer Year Released Wave UPC you have TOTAL Notes Number Price to sell Last Updated: April 13, 2015 Questions/Concerns/Other Full Name: Address: Delivery Address: W730 State Road 35 Phone: Fountain City, WI 54629 Tel: 608.687.7572 ext: 3 E-mail: Referred By (please fill in) Fax: 608.687.7573 Email: [email protected] Guidelines for Brian’s Toys will require a list of your items if you are interested in receiving a price quote on your collection. It is very important that we Note: Buylist prices on this sheet may change after 30 days have an accurate description of your items so that we can give you an accurate price quote. By following the below format, you will help Selling Your Collection ensure an accurate quote for your collection. As an alternative to this excel form, we have a webapp available for http://buylist.brianstoys.com/lines/Marvel/toys . STEP 1 Please note: Yellow fields are user editable. You are capable of adding contact information above and quantities/notes below. Before we can confirm your quote, we will need to know what items you have to sell. The below list is by Marvel category. Search for each of your items and enter the quantity you want to sell in column I (see red arrow). (A hint for quick searching, press Ctrl + F to bring up excel's search box) The green total column will adjust the total as you enter in your quantities. -

Hasbro Closes Acquisition of Saban Properties' Power Rangers And

Hasbro Closes Acquisition of Saban Properties’ Power Rangers and other Entertainment Assets June 12, 2018 PAWTUCKET, R.I.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jun. 12, 2018-- Hasbro, Inc. (NASDAQ: HAS) today announced it has closed the previously announced acquisition of Saban Properties’ Power Rangers and other Entertainment Assets. The transaction was funded through a combination of cash and stock valued at $522 million. “Power Rangers will benefit from execution across Hasbro’s Brand Blueprint and distribution through our omni-channel retail relationships globally,” said Brian Goldner, Hasbro’s chairman and chief executive officer. “Informed by engaging, multi-screen entertainment, a robust and innovative product line and consumer products opportunities all built on the brand’s strong heritage of teamwork and inclusivity, we see a tremendous future for Power Rangers as part of Hasbro’s brand portfolio.” Hasbro previously paid Saban Brands$22.25 million pursuant to the Power Rangers master toy license agreement, announced by the parties in February of 2018, that was scheduled to begin in 2019. Those amounts were credited against the purchase price. Upon closing, Hasbro paid $131.23 million in cash (including a $1.48 million working capital purchase price adjustment) and $25 million was placed into an escrow account. An additional $75 million will be paid on January 3, 2019. These payments are being funded by cash on the Company’s balance sheet. In addition, the Company issued 3,074,190 shares of Hasbro common stock to Saban Properties, valued at $270 million. The transaction, including intangible amortization expense, is not expected to have a material impact on Hasbro’s 2018 results of operations. -

Masters of the Universe: Action Figures, Customization and Masculinity

MASTERS OF THE UNIVERSE: ACTION FIGURES, CUSTOMIZATION AND MASCULINITY Eric Sobel A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2018 Committee: Montana Miller, Advisor Esther Clinton Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Montana Miller, Advisor This thesis places action figures, as masculinely gendered playthings and rich intertexts, into a larger context that accounts for increased nostalgia and hyperacceleration. Employing an ethnographic approach, I turn my attention to the under-discussed adults who comprise the fandom. I examine ways that individuals interact with action figures creatively, divorced from children’s play, to produce subjective experiences, negotiate the inherently consumeristic nature of their fandom, and process the gender codes and social stigma associated with classic toylines. Toy customizers, for example, act as folk artists who value authenticity, but for many, mimicking mass-produced objects is a sign of one’s skill, as seen by those working in a style inspired by Masters of the Universe figures. However, while creativity is found in delicately manipulating familiar forms, the inherent toxic masculinity of the original action figures is explored to a degree that far exceeds that of the mass-produced toys of the 1980s. Collectors similarly complicate the use of action figures, as playfully created displays act as frames where fetishization is permissible. I argue that the fetishization of action figures is a stabilizing response to ever-changing trends, yet simultaneously operates within the complex web of intertexts of which action figures are invariably tied. To highlight the action figure’s evolving role in corporate hands, I examine retro-style Reaction figures as metacultural objects that evoke Star Wars figures of the late 1970s but, unlike Star Wars toys, discourage creativity, communicating through the familiar signs of pop culture to push the figure into a mental realm where official stories are narrowly interpreted. -

History of the World Rulebook

TM RULES OF PLAY Introduction Components “With bronze as a mirror, one can correct one’s appearance; with history as a mirror, one can understand the rise and fall of a state; with good men as a mirror, one can distinguish right from wrong.” – Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty History of the World takes 3–6 players on an epic ride through humankind’s history. From the dawn of civilization to the twentieth century, you will witness humanity in all its majesty. Great minds work toward technological advances, ambitious leaders inspire their 1 Game Board 150 Armies citizens, and unpredictable calamities occur—all amid the rise and fall (6 colors, 25 of each) of empires. A game consists of five epochs of time, in which players command various empires at the height of their power. During your turn, you expand your empire across the globe, gaining points for your conquests. Forge many a prosperous empire and defeat your adversaries, for at the end of the game, only the player with the most 24 Capitols/Cities 20 Monuments (double-sided) points will have his or her immortal name etched into the annals of history! Catapult and Fort Assembly Note: The lighter-colored sides of the catapult should always face upward and outward. 14 Forts 1 Catapult Egyptians Ramesses II (1279–1213 BCE) WEAPONRY I EPOCH 4 1500–450 BCE NILE Sumerians 3 Tigris – Empty Quarter Egyptians 4 Nile Minoans 3 Crete – Mediterranean Sea Hittites 4 Anatolia During this turn, when you fight a battle, Assyrians 6 Pyramids: Build 1 monument for every Mesopotamia – Empty Quarter 1 resource icon (instead of every 2). -

Ah-80Catalog-Alt

STRATEGY GAME CATALOG I Reaching our Peek! FEATURING BATTLE, COMPUTER, FANTASY, HISTORICAL, ROLE PLAYING, S·F & ......\Ci l\\a'C:O: SIMULATION GAMES REACHING OUR PEEK Complexity ratings of one to three are introduc tory level games Ratings of four to six are in Wargaming can be a dece1v1ng term Wargamers termediate levels, and ratings of seven to ten are the are not warmongers People play wargames for one advanced levels Many games actually have more of three reasons . One , they are interested 1n history, than one level in the game Itself. having a basic game partlcularly m1l11ary history Two. they enroy the and one or more advanced games as well. In other challenge and compet111on strategy games afford words. the advance up the complexity scale can be Three. and most important. playing games is FUN accomplished within the game and wargaming is their hobby The listed playing times can be dece1v1ng though Indeed. wargaming 1s an expanding hobby they too are presented as a guide for the buyer Most Though 11 has been around for over twenty years. 11 games have more than one game w1th1n them In the has only recently begun to boom . It's no [onger called hobby, these games w1th1n the game are called JUSt wargam1ng It has other names like strategy gam scenarios. part of the total campaign or battle the ing, adventure gaming, and simulation gaming It game 1s about Scenarios give the game and the isn 't another hoola hoop though. By any name, players variety Some games are completely open wargam1ng 1s here to stay ended These are actually a game system. -

View from the Trenches Avalon Hill Sold!

VIEW FROM THE TRENCHES Britain's Premier ASL Journal Issue 21 September '98 UK £2.00 US $4.00 AVALON HILL SOLD! IN THIS ISSUE HIT THE BEACHES RUNNING - Seaborne assaults for beginners SAVING PRIVATE RYAN - Spielberg's New WW2 Movie LANDING CRAFT FLOWCHART - LC damage determination made easy GOLD BEACH - UK D-Day Convention report IN THIS ISSUE PREP FIRE Hello and welcome the latest issue of View From The Trenches. PREP FIRE 2 The issue is slightly bigger than normal due to Greg Dahl’s AVALON HILL SOLD 3 excellent but rather large article and accompanying flowchart dealing with beach assaults. Four extra pages for the same price. Can’t be INCOMING 4 bad. SCOTLAND THE BRAVE 5 In keeping with the seaborne theme there is also a report on the replaying of the Monster Scenarios ‘Gold Beach’ scenario in the D-DAY AT GOLD BEACH 6 D-Day museum in June, and a review of the new Steve Spielberg WW2 movie, Saving Private Ryan. HIT THE BEACHES RUNNING! 7 I hope to be attending ASLOK this year, so I’m not sure if the “THIS IS THE CALL TO ARMS!” 9 next issue will be out at INTENSIVE FIRE yet. If not, it’ll be out soon after IF’98. THE CRUSADERS 12 While on the subject of conventions, if anyone is planning on SAVING PRIVATE RYAN 18 attending the German convention GRENADIER ’98 please get in touch with me. If we can get enough of us to go as a group, David ON THE CONVENTION TRAIL 19 Schofield may be able to organise transport for all us. -

Playing Purple in Avalon Hill Britannia

Sweep of History Games Magazine #2 Page 1 Sweep of History Games Magazine #2, Spring 2006. Published and edited by Dr. Lewis Pulsipher, [email protected]. This approximately quarterly electronic magazine is distributed free via http://www.pulsipher.net/sweepofhistory/index.htm, and via other outlets. The purpose of the magazine is to entertain and educate those interested in games related to Britannia ("Britannia-like games"), and other games that cover a large geographical area and centuries of time ("sweep of history games"). Articles are copyrighted by the individual authors. Game titles are trademarks of their respective publishers. As this is a free magazine, contributors earn only my thanks and the thanks of those who read their articles. This magazine is about games, but we will use historical articles that are related to the games we cover. This copyrighted magazine may be freely distributed (without alteration) by any not-for-profit mechanism. If you are in doubt, write to the editor/publisher. The “home” format is PDF (saved from WordPerfect); it is also available as unformatted HTML (again saved from WP) at www.pulsipher.net/sweepofhistory/index.htm. Table of Contents strategy article in Issue 1, is one of the “sharks” from the World Boardgaming Championships. 1 Introduction Nick has twice won the Britannia tournament 1 Playing Purple in Avalon Hill there, and is also (not surprisingly) successful at Britannia by Nick Benedict WBC Diplomacy. 7 Britannia by E-mail by Jaakko Kankaanpaa 11 Review of game Mesopotamia: I confess, I’m fascinated to see what strategies the “sharks” will devise for the Second Edition, which by George Van Voorn Birth of Civilisation I understand will be used at this year’s 12 Trying to Define Sweep of History tournament. -

Domain Specific Techniques for Creating Games

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Major Qualifying Projects (All Years) Major Qualifying Projects April 2007 Domain Specific echniquesT for Creating Games Jeremiah J. Chaplin Worcester Polytechnic Institute Micah D. Gaulin-McKenzie Worcester Polytechnic Institute Michael Anthony Anastasia Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/mqp-all Repository Citation Chaplin, J. J., Gaulin-McKenzie, M. D., & Anastasia, M. A. (2007). Domain Specific eT chniques for Creating Games. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/mqp-all/1348 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Major Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Project Number. GFP0607 Domain Specific Techniques for Creating Games A Major Qualifying Project Report: submitted to the faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by: ___________________________ Michael Anastasia ___________________________ Jeremiah Chaplin ___________________________ Micah Gaulin-McKenzie ___________________________ April 25, 2007 Approved: ______________________________ Professor Gary F. Pollice, Major Advisor 1. Domain-Specific Languages 2. Strategic games 3. Code Generation Abstract Modern game development projects rely on specialized tools for physics, graphics, -

View Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT To Our Shareholders There is no better mission in life than “Making the World Smile!” At Hasbro, our business is built on fun, and our nearly 6,000 employees worldwide are all focused on bringing joy and exciting play experiences to millions of kids and families across the globe. You can see this commitment and passion in everything we do --- from the toys, games and licensed products we bring to market, to how we manage our business, and create value for our shareholders. As you read about all of the great things happening within your company, we hope that Hasbro brings out the kid in all of you and that you continue to personally discover the magic within our brands! 2007 Highlights In 2007, Hasbro had a very strong year and delivered record-breaking results, in spite of the challenges facing the toy industry. We started 2007 strong, performed well throughout the year, and fi nished with a robust fourth quarter, even though the industry saw a holiday season that was negatively affected by a weak retail environment and the impact of the lead paint recalls. We were proud that Hasbro avoided any lead paint recalls --- a tribute to our commitment to product safety. Our growth was broad based, both in terms of geography and product categories, and we continued to drive innovation in all aspects of our business. All in all, Hasbro had an extraordinary year! We have accomplished a great deal over the past six years --- growing revenues at a compounded annual growth rate of over 6%, surpassing our longer-term goal of 3-5% per year, and achieving an operating margin of 13.5%, also exceeding our target of 12% or better, set several years ago. -

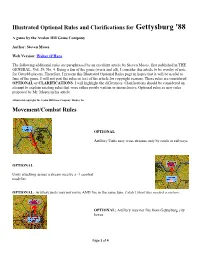

Illustrated Optional Rules and Clarifications for Gettysburg '88

Illustrated Optional Rules and Clarifications for Gettysburg '88 A game by the Avalon Hill Game Company Author: Steven Moses Web Version: Walter O'Hara The following additional rules are paraphrased by an excellent article by Steven Moses, first published in THE GENERAL, Vol. 29, No. 4. Being a fan of the game (warts and all), I consider this article to be worthy of note for Getty88 players. Therefore, I present this Illustrated Optional Rules page in hopes that it will be useful to fans of the game. I will not post the rules or text of the article for copyright reasons. These rules are considered OPTIONAL or CLARIFICATIONS. I will highlight the differences. Clarifications should be considered an attempt to explain existing rules that were either poorly written or inconclusive, Optional rules as new rules proposed by Mr. Moses in his article. All material copyright, the Avalon Hill Game Company, Hasbro, Inc. Movement/Combat Rules OPTIONAL Artillery Units may cross streams only by roads or railways. OPTIONAL Units attacking across a stream receive a -1 combat modifier. OPTIONAL: Artillery units may not move AND fire in the same turn. I didn't think this needed a picture... OPTIONAL: Artillery may not fire from Gettysburg city hexes. Page 1 of 4 CLARIFICATION: Units entering board in same hex must enter in column. The yellow markers indicate the movement costs for entry. OPTIONAL: Units may not use the road bonus within two hexes (inclusive) of enemy artillery. Stacking Units CLARIFICATION: Any number of Generals can stack together. OPTIONAL: Two Cavalry units from the same corps/division (only) may stack together. -

143 West 29Th Street, Suite 1101

Paul Kurnit Clinical Professor Of Marketing, Pace University President, PS Insights Paul Kurnit is an internationally recognized marketing professional with over 25 years in the advertising and entertainment businesses. Paul began his advertising career at Benton & Bowles and Ogilvy & Mather, where he managed a number of classic brands for Procter & Gamble, Kraft, American Express and Hasbro. As President and Chief Operating Officer at Griffin Bacal (a DDB agency), Paul managed accounts across a wide range of consumer and BtoB brands. He was also Executive Vice President of Sunbow Entertainment, a leading producer of quality children’s television programming. Paul is an expert in social and cultural trends having created a number of specialty business units dedicated to addressing a diverse range of marketing initiatives, including: LiveWire: Today’s Families Online® Kid Think Inc.™ Licensing Works!™ Trend Walk™ TDC: The Design Group The Digital Station As founder of Kurnit Communications, KidShop and PSInsights, Paul has been dedicated to delivering customized marketing solutions for companies seeking dramatic new initiatives to drive their businesses. Paul is a frequent speaker and writer for television, radio and print media (NBC/The Today Show, ABC, CBS News, CNN, Fox, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, USA Today, Barron’s, Ad Age, AdWeek, BrandWeek, Entrepreneur and more). He has shared his expertise in consulting work for Bayer, ConAgra, Disney, General Mills, Hasbro, McDonald’s, Nickelodeon, Pepsi, Scholastic, Sony, Universal Studios and many other blue chip and start up companies. Paul is on the boards and advisory boards of several industry organizations including The Advertising Educational Foundation (AEF), the Children’s Advertising Review Unit (CARU) of the Better Business Bureau and the International Journal of Advertising and Marketing to Children. -

The General Vol 13 No 1

GENERAL PAGE 2 THEGENERAL I 1 Analon HiU Philosophy Part 55 I The Game Players Magazine UPCOMING GAMES I The Avalon Hill GENERAL 1% if6dicated ta the preen Early indications are that 1976 has brought invasions of Russia from four different perids lion of authoritatiue articles on the strategy, tactics, a an acceleration to the already hectic newgame are recreated.Thefour different invaders are the variation of Avalon Hill games of sitategv. Histerkl artrc pace. We now have more titles under active Mongols, Charles the XII, Napoleon and Hitler's are Included only inmuch a9 they provide useful ba @round information on current Avelon Hill t~tles. T development than at any other time during our Operation Barbarossa. Turns are weekly with no GENERAL is PuMished by thn Avalon HIH Corr@arry 501 history. To help out with our increasedworkload version lasting more than 6 months. Originally , for the cultural edlfimtion wi the seriouagamaficionado - the hopes of Improving the game ownw'sproficieplcy o+ pla we've added another full time developer in the planned for releaseat ORIGINS 11,4 ROADS has and oroviding services not otherwiw nvailablm to the Avalo form of A. Richard Harnblen, an inveterate run into problems in development and probably HIII gams bufl. wargame designer and player of long standing. will not be available before fall. Publication 3s bi-monthly with mailingsmadsclose to SQUAD LEADER is a game we're pretty the end of February, Aprrl. June, August. Octohr, and Among other things, Richard brings us an Ducember All Bdltorial and general maif should besent to immense amount of expertise on the American excited about.