Ushio Shinohara, Boxing Painting, 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street Into 'Theatre,' Circa 1964 Tokyo

Performance Paradigm 2 (March 2006) Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street into ‘Theatre,’ Circa 1964 Tokyo Midori Yoshimoto Performance art was an integral part of the urban fabric of Tokyo in the late 1960s. The so- called angura, the Japanese abbreviation for ‘underground’ culture or subculture, which mainly referred to film and theatre, was in full bloom. Most notably, Tenjô Sajiki Theatre, founded by the playwright and film director Terayama Shûji in 1967, and Red Tent, founded by Kara Jûrô also in 1967, ruled the underground world by presenting anti-authoritarian plays full of political commentaries and sexual perversions. The butoh dance, pioneered by Hijikata Tatsumi in the late 1950s, sometimes spilled out onto streets from dance halls. Students’ riots were ubiquitous as well, often inciting more physically violent responses from the state. Street performances, however, were introduced earlier in the 1960s by artists and groups, who are often categorised under Anti-Art, such as the collectives Neo Dada (originally known as Neo Dadaism Organizer; active 1960) and Zero Jigen (Zero Dimension; active 1962-1972). In the beginning of Anti-Art, performances were often by-products of artists’ non-conventional art-making processes in their rebellion against the artistic institutions. Gradually, performance art became an autonomous artistic expression. This emergence of performance art as the primary means of expression for vanguard artists occurred around 1964. A benchmark in this aesthetic turning point was a group exhibition and outdoor performances entitled Off Museum. The recently unearthed film, Aru wakamono-tachi (Some Young People), created by Nagano Chiaki for the Nippon Television Broadcasting in 1964, documents the performance portion of Off Museum, which had been long forgotten in Japanese art history. -

Cutie and the Boxer, 1/11/2013

CUTIE AND THE BOXER, 1/11/2013 PRESENTS A FILM BY ZACHARY HEINZERLING CUTIE AND THE BOXER US|HD UK THEATRICAL RELEASE: 1 Nov, 2013 RUNNING TIME: 82 minutes Press Contact: Yung Kha T. 0207 831 7252 [email protected] Web: http://cutieandtheboxer.co.uk/ Twitter: @CutieAndBoxer Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/cutieandtheboxer CUTIE AND THE BOXER, 1/11/2013 SHORT SYNOPSIS A reflection on love, sacrifice, and the creative spirit, this candid New York story explores the chaotic 40- year marriage of renowned “boxing” painter Ushio Shinohara and his artist wife, Noriko. As a rowdy, confrontational young artist in Tokyo, Ushio seemed destined for fame, but met with little commercial success after he moved to New York City in 1969, seeking international recognition. When 19-year-old Noriko moved to New York to study art, she fell in love with Ushio—abandoning her education to become the wife and assistant to an unruly, husband. Over the course of their marriage, the roles have shifted. Now 80, Ushio struggles to establish his artistic legacy, while Noriko is at last being recognized for her own art—a series of drawings entitled “Cutie,” depicting her challenging past with Ushio. Spanning four decades, the film is a moving portrait of a couple wrestling with the eternal themes of sacrifice, disappointment and aging, against a background of lives dedicated to art. LONG SYNPOSIS Cutie and the Boxer is an intimate, observational documentary chronicling the unique love story between Ushio and Noriko Shinohara, married Japanese artists living in New York. Bound by years of quiet resentment, disappointments and missed professional opportunities, they are locked in a hard, dependent love. -

2012 SUNY New Paltzdownload

New York Conference on Asian Studies September 28 –29, 2012 ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ NYCAS 12 Conference Theme Contesting Tradition State University of New York at New Paltz Executive Board New York Conference on Asian Studies Patricia Welch Hofstra University NYCAS President (2005-2008, 2008-2011, 2011-2014) Michael Pettid (2008-2011) Binghamton University, SUNY Representative to the AAS Council of Conferences (2011-2014) Kristin Stapleton (2008-2011, 2011-2014) University at Buffalo, SUNY David Wittner (2008-2011, 2011-2014) Utica College Thamora Fishel (2009-2012) Cornell University Faizan Haq (2009-2012) University at Buffalo, SUNY Tiantian Zheng (2010-2013) SUNY Cortland Ex Officio Akira Shimada (2011-2012) David Elstein (2011-2012) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS 12 Conference Co-Chairs Lauren Meeker (2011-2014) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Treasurer Ronald G. Knapp (1999-2004, 2004-2007, 2007-2010, 2010-2013) SUNY New Paltz NYCAS Executive Secretary The New York Conference on Asian Studies is among the oldest of the nine regional conferences of the Association for Asian Studies (AAS), the largest society of its kind in the world. NYCAS is represented on the Council of Conferences, one of the sub-divisions of the governing body of the AAS. Membership in NYCAS is open to all persons interested in Asian Studies. It draws its membership primarily from New York State but welcomes participants from any region interested in its activities. All persons registering for the annual meeting pay a membership fee to NYCAS, and are considered members eligible to participate in the annual business meeting and to vote in all NYCAS elections for that year. -

Ushio Shinohara Maltese Falcon

MEDIA RELEASE For more information contact: Deborah M. Colton 713.869.5151 [email protected] Ushio Shinohara Maltese Falcon January 11, 2020 through February 29, 2020 Public Opening Reception: Saturday, January 11th from 6:00 to 8:00 pm Deborah Colton Gallery is pleased to present Ushio Shinohara: Maltese Falcon. The exhibition features the newest works by the internationally acclaimed Japanese artist, Ushio Shinohara, whose performative paintings are created with boxing gloves he uses like paintbrushes. His flashy, multicolored three- dimensional sculptures are also included in the exhibition, which nearly vibrates with the energy of the works that comprise the show. There is a public opening reception on Saturday, January 11th from 6:00 to 8:00 pm. Born in Tokyo in 1932, Ushio Shinohara (nicknamed "Gyu-chan") is a Japanese Neo-Dadaist artist and International Pop painter who has lived and worked in the United States since 1969. His parents, a tanka poet and Japanese painter, instilled in him a love for artists such as Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin. Most recently known for his exuberant boxing paintings, which are artifacts of his performances, Ushio Shinohara works in several mediums, including painting, printmaking, drawing and sculpture. His work was first featured at Deborah Colton Gallery in the grand exhibition Love is a Roar-r-r!, along side works of his wife, artist Noriko Shinohara, whose series Cutie and the Bullie tells the story of their tumultuous relationship. Both were featured in the Oscar and Academy Award nominated documentary, Cutie and the Boxer, which depicts their more than 40-year relationship as a couple and as artists. -

The J. Paul Getty Trust 2007 Report the J

THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 2007 REPORT THE J. PAUL GETTY TRUST 2007 REPORT 4 Message from the Chair 7 Foreword 10 The J. Paul Getty Museum Acquisitions Exhibitions Scholars Councils Patrons Docents & Volunteers 26 The Getty Research Institute Acquisitions Exhibitions Scholars Council 38 The Getty Conservation Institute Projects Scholars 48 The Getty Foundation Grants Awarded 64 Publications 66 Staff 73 Board of Trustees, Offi cers & Directors 74 Financial Information e J. Paul Getty Trust The J. Paul Getty Trust is an international cultural and philanthropic institution that focuses on the visual arts in all their dimensions, recognizing their capacity to inspire and strengthen humanistic values. The Getty serves both the general public and a wide range of professional communities in Los Angeles and throughout the world. Through the work of the four Getty programs–the Museum, Research Institute, Conservation Institute, and Foundation–the Getty aims to further knowledge and nurture critical seeing through the growth and presentation of its collections and by advancing the understanding and preservation of the world’s artistic heritage. The Getty pursues this mission with the conviction that cultural awareness, creativity, and aesthetic enjoyment are essential to a vital and civil society. e J. Paul Getty Trust 3 Message from the Chair e 2007 fi scal year has been a time of progress and accomplishment at the J. Paul Getty Trust. Each of the Getty’s four programs has advanced signifi cant initiatives. Agreements have been reached on diffi cult antiquities claims, and the challenges of two and three years ago have been addressed by the implementation of new policies ensuring the highest standards of governance. -

CHNJP12-Mod Japan-1

Collision Cultures Modern Art in Japan Chronicle of the Imperial Restoration Taiso Yoshitoshi, 1876. Biographies of Modern Men, 1865. Taiso Yoshitoshi Complete Enumeration of Scenic Places in Foreign Nations: City of Washington in America. 1862, by Yoshitora. Main Street of Agra, Illustrated London News, 27 Nov. 1858. Nagasaki-e cigarettes quickly replaced pipe smoking and was monopolized by the Yokohama government to raise revenue for the military expansion. Prints Among the People of All Nations: Americans, 1861, by Kuniaki II Note that the audience is westerners sitting in chairs and also that the stage assistants are visible. Picture Amusements of Foreigners in James Audubon, anon. Yok ohama, 1861 by Yoshitora Meiji Era. Motherhood in Modern Japan He was one of eleven Japanese print artists who showed their works at the Paris Exposition of 1866, for which he received the Légion d'Honneur. Sadahide's works incorporated the Western technique of shading, seen here on the barrel and the folds of the clothing. Sadahide (1807-73), European Toy Stall,1860. 'Dōban e-jō saishiki' ('Hand-colored copperplate print') An eccentric correspondent for the London Illustrated News, Charles Wirgman (1835-1891), was the first to bring comics ashore. One year after his arrival in Japan in 1863, Wirgman published the Japan Punch, which was modeled on the British Punch and was published more or less monthly until 1887. Each slim ten-page issue was produced in the same manner as traditional woodblock prints, which The Japan Punch by ponchi-e had been available in Japan since the early 16th century. Wirgman Charles Wigman, 1862-1887 tailored his humor magazine for the growing expatriate audience in Yokohama by showing cartoons in a manner typical of British satire of the time. -

Readily “There Is No Definition of Art,” What They Mean to Say Is “There Is No ONE Definition of Speak Each Other’S Languages

free Daria Martin, Sensorium Tests. 16mm film, 10 minutes. 2012. © the artist, courtesy Maureen Paley, London. SFAQ + Kadist Art Foundation Jan 29–MaY 25 80 ARTISTS 9 STUDIOS 17 WORKSHOPS CURATED BY Public Intimacy: Art and Other Ordinary Acts in South Africa is jointly organized by YBCA and SFMOMA. Presenting support is generously provided by the Evelyn D. Haas Exhibition Fund at SFMOMA. DAVID WILSON Major support is provided by the James C. Hormel and Michael P. Nguyen Endowment Fund at SFMOMA, Meridee Moore and Kevin King, the Betlach Family Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, Mike Wilkins and Sheila Duignan, and the YBCA Creative Ventures Council. Additional support is provided by the George Frederick Jewett Foundation and the Yerba Buena Community Benefit District. MEDIA SPONSOR: make@ UC Berkeley Art MUseUM & PACifiC filM ArChive bampfa.berkeley.edu IMAGE: Athi-Patra Ruga, The Future White Women of Azania, 2012; performed as part of Performa Obscura in collaboration with Mikhael Subotzky; commissioned for the exhibition Making Way, Grahamstown, South Africa; photo: Ruth Simboa, courtesy Athi-Patra Ruga and WHATIFTHEWORLD/GALLERY. YERBA BUENA CENTER FOR THE ARTS • YBCA.ORG • 415.978.ARTS Possible_sfaq.indd 1 12/16/13 10:20 AM ASIAN ART MUSEUM THROUGH FEB 23, 2014 www.asianart.org The concept that almost everyone touches something that is conceived, mined, manufactured, or outsourced in Asia informs this final installment of our contemporary art series, Proximities. Bay Area artists Rebeca Bollinger, Amanda Curreri, Byron Peters, Jeffrey Augustine Songco, Leslie Shows and Imin Yeh examine ways in which trade and commerce contribute to impressions of Asia. -

Japan Society Timeline

JAPAN SOCIETY TIMELINE 1907 1911 1918 May 19 , 1907 : Japan Society founded by Annual lecture series initiated (lectures Japan Society Bulletin of February 28 , 1918 , Lindsay Russell, Hamilton Holt, Jacob Schiff, usually held at the Hotel Astor or at The exhorted readers: “Isn’t it worth your while August Belmont, and other prominent Metropolitan Museum of Art, drawing to spend fifteen minutes a month on Japan? Americans on the occasion of the May visit several hundred people); lectures from The day has passed when we needed to think to New York by General Baron Tamesada the first year included Toyokichi Ienaga only in terms of our own country. The inter - Kuroki and Vice Admiral Goro Ijuin. on “The Positions of the United States and national mind is of today. Read this Bulletin Japan in the Far East” and Frederick W. of the Japan Society and learn something John H. Finley, president of City College, Gookin on Japanese color prints. new about your nearest Western neighbor. elected Japan Society’s first president. Japan has much to teach us. Preparedness is Japan Society’s first art exhibition held Purpose of the Society set forth as “the pro - the watchword of the day: don’t forget that (ukiyo-e prints borrowed from private motion of friendly relations between the this includes mental preparedness. It is just collections and shown at 200 Fifth Avenue), United States and Japan and the diffusion as important to think straight as to shoot attended by about 8,000 people. among the American people of a more accu - straight. -

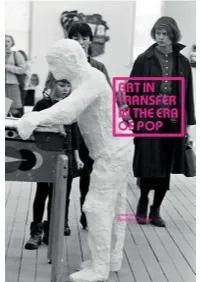

Art in Transfer in the Era of Pop

ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP ART IN TRANSFER IN THE ERA OF POP Curatorial Practices and Transnational Strategies Edited by Annika Öhrner Södertörn Studies in Art History and Aesthetics 3 Södertörn Academic Studies 67 ISSN 1650-433X ISBN 978-91-87843-64-8 This publication has been made possible through support from the Terra Foundation for American Art International Publication Program of the College Art Association. Södertörn University The Library SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications © The authors and artists Copy Editor: Peter Samuelsson Language Editor: Charles Phillips, Semantix AB No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Cover Image: Visitors in American Pop Art: 106 Forms of Love and Despair, Moderna Museet, 1964. George Segal, Gottlieb’s Wishing Well, 1963. © Stig T Karlsson/Malmö Museer. Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Graphic Form: Per Lindblom & Jonathan Robson Printed by Elanders, Stockholm 2017 Contents Introduction Annika Öhrner 9 Why Were There No Great Pop Art Curatorial Projects in Eastern Europe in the 1960s? Piotr Piotrowski 21 Part 1 Exhibitions, Encounters, Rejections 37 1 Contemporary Polish Art Seen Through the Lens of French Art Critics Invited to the AICA Congress in Warsaw and Cracow in 1960 Mathilde Arnoux 39 2 “Be Young and Shut Up” Understanding France’s Response to the 1964 Venice Biennale in its Cultural and Curatorial Context Catherine Dossin 63 3 The “New York Connection” Pontus Hultén’s Curatorial Agenda in the -

Interview with Miwako Tezuka by Diana Seo Hyung Lee

ArtAsiaPacific Magazine Multimedia News Blog Countries About Shop DEC 16 2016 JAPAN USA FROM EIGHT HOURS TO THE PRESENT: INTERVIEW WITH MIWAKO TEZUKA BY DIANA SEO HYUNG LEE ArtAsiaPacific sat down with Miwako Tezuka to discuss her work as consulting curator of New York’s Reversible Destiny Foundation, created by the artist couple Shusaku Arakawa (1936–2010) and Madeline Gins (1941–2014) in 2010. Formerly the associate curator at the Asia Society in New York, Tezuka played a pivotal role in developing the institution’s program of contemporary Asian and Asian American artists. She oversaw Asia Socety’s “In Focus” series, a platform for solo exhibitions where artists are invited to select objects from Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection of Asian Art at the Asia Society Museum as inspiration for new creations. Through this series, Tezuka presented solo shows by artists such as Yuken Teruya from Okinawa (2/20/07–4/27/07), Suda Yoshihiro from Tokyo (10/6/09–2/7/10) and U-Ram Choe from Seoul (9/9/11–12/31/11). Immediately before her transition to the Reversible Destiny Foundation, Tezuka was the gallery director of the Japan Society, where she curated the well-received “Garden of Unearthly Delights: Works by Ikeda, Tenmyouya & teamLab” (10/10/14–1/11/15), among others. While the architecture-based practice of the dynamic Arakawa and Gins has largely been under the art world’s radar, the couple has left an extraordinary body Portrait of curator Miwako Tezuka of Reversible Destiny Foundation in of work that blurs the boundaries between genres and lies across the New York. -

Exploring Japanese Avant-Garde Art Through Butoh Dance

Week1 Exploring Japanese Avant-garde Art Through Butoh Dance Handout English Version Week 1 Towards butoh: Experimentation Week 2 Dancing butoh: Embodiment Week 3 Behind butoh: Creation Week 4 Expanding butoh: Globalisation © Keio University 2019/1/6 Butoh_Week1 - Google ドキュメント Week1 Towards butoh: Experimentation WEEK 1: TOWARDS BUTOH: EXPERIMENTATION Activity 1: Introduction of the course First of all, let's watch butoh. 1.1 WELCOME TO THE WORLD OF JAPANESE AVANT-GARDE ART VIDEO (01:38) 1.2 FIRST OF ALL, LET'S SEE BUTOH ARTICLE 1.3 WHAT IS BUTOH? ARTICLE 1.4 THE BACKGROUND OF BUTOH ARTICLE Activity 2: Post-war Tokyo and the birth of Butoh Let's take a closer look at Tatsumi Hijikata himself who created butoh, as well as the social background of 1950's in Japan. 1.5 POST-WAR RECONSTRUCTION AND HIGH ECONOMIC GROWTH VIDEO (00:58) 1.6 POST-WAR JAPANESE ART ARTICLE 1.7 POST-WAR JAPANESE DANCE ARTICLE 1.8 BEFORE BUTOH VIDEO (02:43) 1.9 THE BIRTH OF BUTOH VIDEO (04:12) 1.10 THE ESTABLISHMENT OF BUTOH ARTICLE 1.11 THE WAR AND THE ART DISCUSSION Activity 3: From "happening dance" to butoh See how Japanese art absorbed, refigured and influenced Western art in the 20th century through Tatsumi Hijikata's butoh dance. 1.12 "NAVEL AND A-BOMB" ARTICLE 1.13 THE AVANT-GARDE AND EXPERIMENTS IN PHYSICAL EXPRESSION ARTICLE 1.14 AVANT-GARDE ART AND ANTI-ART ARTICLE 1.15 THE HAPPENING DANCE ARTICLE Exploring Japanese Avant-garde Art Through Butoh Dance KEIO UNIVERSITY © Keio University https://docs.google.com/document/d/1XGlM_hiVykuLtxRGv_HnU9MafeIMpLihQV0zHzSr_d0/edit# 1/56 2019/1/6 Butoh_Week1 - Google ドキュメント Week1 Towards butoh: Experimentation 1.16 THE FORMATION OF ANKOKU BUTOH VIDEO (02:25) Activity 4: Rebellion of the Body Let's learn through the work of Tatsumi Hijikata and the impact of butoh as an activity in the society. -

2013 ANNUAL REPORT Front and Back Cover: Monkey Journey to the West, Directed by Chen Shi-Zheng, Presented at Lincoln Center Festival in Summer 2013

asian cultural council 2013 ANNUAL REPORT Front and back cover: Monkey Journey to the West, directed by Chen Shi-Zheng, presented at Lincoln Center Festival in summer 2013. II 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 2 Board of Trustees 3 Message from the Executive Director 4 Program Overview and 2013 Grants 14 John D. Rockefeller 3rd Awards 16 Alumni News 20 Events 26 Statement of Activities 27 2013 Donors 29 Partners 32 Staff Surupa Sen (right) and Bijayini Satpathy performing at New York City Center’s Fall for Dance Festival. 1 The Way of Chopsticks: Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen, a site-specific installation created in the fall of 2013 by Song Dong and Yin Xiuzhen for the Philadelphia Art Alliance. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Officers Trustees Life Trustees Wendy O’Neill Hope Aldrich Colin G. Campbell Chairman Jane DeBevoise Kenneth H.C. Fung Valerie Rockefeller Wayne John H. Foster Stephen B. Heintz Vice Chairman Curtis Greer Abby M. O’Neill Hans Michael Jebsen David Halpert Russell A. Phillips, Jr. Vice Chairman Douglas Tong Hsu Robert S Pirie Richard S. Lanier J. Christopher Kojima Isaac Shapiro President Erh-fei Liu Michael I. Sovern Jonathan Fanton Vincent A. Mai Treasurer Ken Miller Pauline R. Yu Josie Cruz Natori Secretary Carol Rattray Elizabeth J. McCormack David Rockefeller, Jr. Chairman Emeritus Lynne Rutkin Marissa Fung Shaw William G. Spears Yuji Tsutsumi as of June 1, 2014 boarD OF TRUSTEES 2 MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 013 marks the 50th anniversary of the Asian celebration was made possible by the dedicated efforts Cultural Council. As we reach this milestone, it from 14 alumni, including Loy Arcenas, Chris Millado, 2is a time to both reflect on the past and envision Gino Gonzales, Edna Vida Froilan, Myra Beltran, Bong the possibilities of our future.