Beyond the Frame Intermedia And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Long 1160 Our 6Esifrienos All Mm I

GRAND RAPIDS Ptisuc ueum A Blue Mark around this notice shows that The Paper that stops when the time it W+ this Subscription runs out with this issue Not forced on any one. Thafi worth Ike and should be renewed ut once to avoid a THE LOWELL LEDGER money and then some, $2.00 per year la ad* break in service. and THE ALTO WEKKLY SOLO vance. VOL. XXVIII, NO. 21 LOWELL, MICHIGAN, OOT. 28, 1920 VOL. XVI, NO. 40 I. $ ® $ ®»ilESTS M QAiOOD IN THE LONG 1160 OUR 6ESIFRIENOS ALL MM I I i' ormer Lowell Business Man Bur- Items Taken From This Paper 25 Receipt of SubBcriptions ii Here Newsy Notes About People and i ied With Masonic Honors. Years Ago Oct. 18-25. with Acknowledged. P!*cei You Know. WALL PAPER Agent lieydlauir, of the 1). G. H. Coutinuing its custom of acknowl- All plush coats, reduced $10.00 at A Checking Account & M. put in 15 to 17 hours during edging receipts of subscriptions Weekes,' adv, ZWiW&i peach shipping season. both new and renewals, The Lowel Announcements out for the mar- John Crawford, of Ionia, was in , Ledger and Alto Weekly Solo appre town over Sunday, riage of Thomas Gougherty and ciatingly reports the following; in Our Bank Kathryn Murphy, of Bowne. L'. B. Williams was here from Glen Gray, Mrs. Grace Vander- J. C. Ball, delegate of Lowell Odd- Lansing for a few days. lip, Otis Potter, George J. Shannon Brighten up your rooms for (i! 'i? fellows to Grand lodge in Lansing, m Frank Thompson, S, F, Beimer, Fred Mrs. -

Technical Barriers and R&D Opportunities for Offshore, Sub-Seabed Geologic Storage of Carbon Dioxide

Technical Barriers and R&D Opportunities for Offshore, Sub-Seabed Geologic Storage of Carbon Dioxide Report Prepared for the Carbon Sequestration Leadership Forum (CSLF) Technical Group By the Offshore Storage Technologies Task Force September 14, 2015 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by participants in the Offshore Storage Task Force: Mark Ackiewicz (United States, Chair); Katherine Romanak, Susan Hovorka, Ramon Trevino, Rebecca Smyth, Tip Meckel (all from the University of Texas at Austin, United States); Chris Consoli (Global CCS Institute, Australia); Di Zhou (South China Sea Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, China); Tim Dixon, James Craig (IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme); Ryozo Tanaka, Ziqui Xue, Jun Kita (all from RITE, Japan); Henk Pagnier, Maurice Hanegraaf, Philippe Steeghs, Filip Neele, Jens Wollenweber (all from TNO, Netherlands); Philip Ringrose, Gelein Koeijer, Anne-Kari Furre, Frode Uriansrud (all from Statoil, Norway); Mona Molnvik, Sigurd Lovseth (both from SINTEF, Norway); Rolf Pedersen (University of Bergen, Norway); Pål Helge Nøkleby (Aker Solutions, Norway) Brian Allison (DECC, United Kingdom), Jonathan Pearce, Michelle, Bentham (both from the British Geological Survey, United Kingdom), Jeremy Blackford (Plymouth Marine Laboratory, United Kingdom). Each individual and their respective country has provided the necessary resources to enable the development of this work. The task force members would like to thank John Huston of Leonardo Technologies, Inc. (United States), for coordinating and managing the information contained in the report. i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides an overview of the current technology status, technical barriers, and research and development (R&D) opportunities associated with offshore, sub-seabed geologic storage of carbon dioxide (CO2). -

The Inflation of Abstraction | the New Yorker

6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker The Art World The Inflation of Abstraction The Met’s show of Abstract Expressionism wants to remake the canon. By Peter Schjeldahl December 31, 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 1/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker Mark Rothko’s “No. 3,” from 1953, his peak year of miracles. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Courtesy ARS he rst room of “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera,” a wishfully canon- T expanding show of painting and sculpture from the past eight decades, at the Metropolitan Museum, affects like a mighty organ chord. It contains the museum’s two best paintings by Jackson Pollock: “Pasiphaë” (1943), a quaking compaction of https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 2/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker mythological elements named for the accursed mother of the Minotaur, and “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” (1950), a singing orchestration of drips in black, white, brown, and teal enamel—bluntly material and, inextricably, sublime. There are six Pollock drawings, too, and “Number 7” (1952), one of his late, return-to- guration paintings in mostly black on white, of an indistinct but hieratic head. The adjective “epic” does little enough to honor Pollock’s mid-century glory, which anchors the standard art-historical saga of Abstract Expressionism—“The Triumph of American Painting,” per the title of a 1976 book on the subject by Irving Sandler —as a revolution that stole the former thunder of Paris and set a stratospheric benchmark for subsequent artists. -

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23

ページ:1/37 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-8212-1029 JASRAC SUNSHINE ISUM-9896-0141 JASRAC IT'S GONNA BE ALRIGHT ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-5696-2991 JASRAC Thank you ISUM-9456-6173 JASRAC LIFE ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-8028-4608 JASRAC Tomorrow ISUM-6164-2103 JASRAC Little Hero ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-3400-5002 NexTone V.O.L ISUM-8964-6568 JASRAC Music Is My Life ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-0056-6569 JASRAC Wake up! ISUM-3920-1425 JASRAC MY FRIEND 19 ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-5968-0141 NexTone WAY OF GLORY ISUM-4568-5680 JASRAC ONE ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-6384-4115 NexTone WISHES ISUM-5012-2991 JASRAC One Love ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-1124-1029 JASRAC Yell ISUM-7840-5002 JASRAC So Special -Version AI- ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-4160-4608 JASRAC アシタノヒカリ ISUM-0692-2103 JASRAC sogood ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-5944-4115 NexTone ココア by MisaChia ISUM-1020-1708 JASRAC Story ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-7456-6568 NexTone さよならの前に ISUM-2432-5002 JASRAC Story(English Version) 369 AAA ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-3344-2596 NexTone ハレルヤ ISUM-9864-0141 JASRAC VOICE ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-7328-6173 NexTone ハレルヤ -Bonus Tracks- ISUM-1256-5286 JASRAC WA Interlude feat.鼓童,Jinmenusagi AI ISUM-5580-2991 JASRAC サンダーロード ↑THE HIGH-LOWS↓ ISUM-7296-2102 JASRAC ぼくの憂鬱と不機嫌な彼女 ISUM-9404-0536 JASRAC Wonderful World feat.姫神 ISUM-1180-4608 JASRAC Nostalgia -

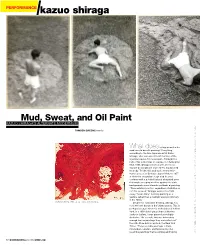

Performance Kazuo Shiraga

PERFORMANCE kazuo shiraga Mud, Sweat, and Oil Paint KAZUO SHIRAGA’S ALTERNATE MODERNIsm. TAMSEN GREENEwords What does rolling around in the mud have to do with painting? Everything, according to the late Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, who was a prominent member of the legendary Gutai Art Association. Although the bulk of his output was on canvas, in Challenging Mud, 1955, Shiraga wrestled with a formless mixture of wall plaster and cement that bruised his body. To him, this and such other perfor- mance pieces as Sanbaso-Super Modern, 1957— in which he swayed on stage clad in a red costume with a pointed hat and elongated arms that made sweeping motions against the dark background—were alternate methods of painting. “There exists my action, regardless of whether or not it is secured,” Shiraga wrote in his 1955 essay “Action Only.” Defining painting as a gesture rather than a medium was revolutionary in the 1950s. Chizensei Kirenji, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS, 51¼ X 63¾ IN. Despite his innovative thinking, Shiraga has not been well known in the United States. This is perhaps because when his work debuted in New York, in a 1958 Gutai group show at Martha Jackson Gallery, it was panned as multiply derivative. “As records, they are interesting enough, but as paintings they are ineffectual,” the critic Dore Ashton wrote in the New York Times. “They resemble paintings in Paris, Amsterdam, London, and Mexico City that resemble paintings that resemble paintings by FROM TOP: THREE IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER; VERVOORDT FOUNDATION COLLECTION. OPPOSITE: BOTH IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER 32 MODERN PAINTERS APRIL 2010 ARTINFO.COM Performance stills from Challenging Mud, third execution. -

Big in Japan at the 1970 World’S Fair by W

PROOF1 2/6/20 @ 6pm BN / MM Please return to: by BIG IN JAPAN 40 | MAR 2020 MAR | SPECTRUM.IEEE.ORG AT THE 1970 WORLD’S FAIR FAIR WORLD’S 1970 THE AT HOW ART, TECH, AND PEPSICO THEN CLASHED TECH, COLLABORATED, ART, HOW BY W. PATRICK M PATRICK W. BY CRAY c SPECTRUM.IEEE.ORG | MAR 2020 MAR | 41 PHOTOGRAPH BY Firstname Lastname RK MM BP EV GZ AN DAS EG ES HG JK MEK PER SKM SAC TSP WJ EAB SH JNL MK (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) Big in Japan I. The Fog and The Floats ON 18 MARCH 1970, a former Japanese princess stood at the tion. To that end, Pepsi directed close to center of a cavernous domed structure on the outskirts of Osaka. US $2 million (over $13 million today) to With a small crowd of dignitaries, artists, engineers, and busi- E.A.T. to create the biggest, most elaborate, ness executives looking on, she gracefully cut a ribbon that teth- and most expensive art project of its time. ered a large red balloon to a ceremonial Shinto altar. Rumbles of Perhaps it was inevitable, but over the thunder rolled out from speakers hidden in the ceiling. As the 18 months it took E.A.T. to design and balloon slowly floated upward, it appeared to meet itself in mid- build the pavilion, Pepsi executives grew air, reflecting off the massive spherical mirror that covered the increasingly concerned about the group’s walls and ceiling. vision. And just a month after the opening, With that, one of the world’s most extravagant and expensive the partnership collapsed amidst a flurry multimedia installations officially opened, and the attendees of recriminating letters and legal threats. -

Theatergoers' Collection Volumes 1~15 Institutional List

The Theater Goer’s Collection (16 Volumes) The Classics of Contemporary Japanese Theater DVDs published by Kazumo Co., Ltd. Tokyo, Japan Volume 1 Himitsu no Hanazono (The Secret Garden) written by Juro Kara, directed by Katsuya Kobayashi Premiere performance of The HONDA Theatre (1982) $ 150. for Institutional Use. Volume 2 Toroia no Onna (The Trojan Women by Euripedes) directed by Tadashi Suzuki and performed by the Suzuki Company of Toga. recorded at 1st International Theater Festival of Toga (1982) Special Feature, Director Tadashi Suzuki in conversation with world-renowned stage director, Peter Brook. $ 150. for Institutional Use. Volume 3 Motto Naiteyo Flapper (Cry Hard, My Dear Flappers) written and directed by Kazuyoshi Kushida, performed by On Theatre Jiyu Gekijo Company at Hakuhinkan Theatre (1983) The first off-broadway musical written and composed by Japanese. $ 150. for Institutional Use. Volume 4 Kirameku Seiza (Twinkle Constellation) written and directed by Hisashi Inoue, the most popular playwright of contemporary Japan a play with popular music from the dark days of Japan, the late ‘30s and ‘40s, (1985) $ 150. for Institutional Use. www.martygrossfilms.com Volume 5 Onna no Isshou (Life of a Woman) written by Kaoru Morimoto, directed by Ichiro Inui performed by The Bungakuza Company featuring stage and screen star, Haruko Sugimura first performed under US Air force bombing in 1945, and revived more than 800 times in the following years. Most popular of all contemporary Japanese plays. Recorded in 1961, (black and white) $ 150. for Institutional Use. Volume 6 Lemming written and directed by Shuji Terayama and performed by the Engeki Jiken Shitsu, Tenjosajiki Company the last play by Terayama prior to his death in 1983 Extra feature: final interview of Shuji Terayama $ 150. -

Acknowledgement to Reviewers of International Journal of Molecular

Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 1336-1374; doi:10.3390/ijms16011336 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Molecular Sciences ISSN 1422-0067 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms Editorial Acknowledgement to Reviewers of the International Journal of Molecular Sciences in 2014 IJMS Editorial Office, MDPI AG, Klybeckstrasse 64, CH-4057 Basel, Switzerland Published: 7 January 2015 The editors of the International Journal of Molecular Sciences would like to express their sincere gratitude to the following reviewers for assessing manuscripts in 2014: Abass, Khaled Agterberg, Martijn J. H. Aleman, Tomas S. Abbott, David H. Aguilar, Claudio Alexander, David Earl Abdelmohsen, Kotb Aguilar-Reina, José Alexander, Stephanie Abdraboh, Mohamed Agulló-Ortuño, M. Teresa Alexiou, Christoph Abe, Naohito Agyei, Dominic Alexis, Frank Abe, Toshiaki Ahmed, Khalil Alexopoulos, A. Abou Neel, Ensanya A. Ahmed, Salahuddin Alfandari, Dominique Abou-Alfa, Ghassan Ahn, Joong-Hoon Alhede, Morten Abraini, Jacques H. Ahn, Suk-Kyun Alisi, Anna Abram, Florence Aibner, Thomas Alison, Malcolm R. Abusco, Anna Scotto Aizawa, Shin-Ichi Al-Kateb, Huda Abzalimov, Rinat Ajikumar, Parayil Kumaran Allen, Randy Ackland, K. Akashi, Makoto Aller, Patricio Acuna-Castroviejo, Darío Akbar, Sheikh Mohammad Fazle Almagro, Lorena Acunzo, M. Akbarzadeh, A. H. Almeida, Raquel Adamcakova-Dodd, Andrea Akeda, Koji Alonso-Nanclares, Lidia Adeniji, Adegoke Akimoto, Jun Alpini, Gianfranco Adessi, Alessandra Aktas, C. Alric, Jean Adhikary, Amitava Akue, Jean Paul Altenbach, Susan B. Afseth, Nils Al Ghouleh, Imad Altmann, André Agalliu, Dritan Al-Ahmadie, Hikmat A. Alvarez Ponces, David Agarwal, Anika Alber, Birgit E. Alvarez-Suarez, José M. Ageorges, Agnès Albero, Cenci Alves, Artur Agorastos, Agorastos Alcaro, Stefano Amacher, David E. Agostini, Marco Alemán, José Amado, Francisco Int. -

THE WORKS of NAKAJIMA ATSUSHI "War Is War and Literature Is Literature"

THE WORKS OF NAKAJIMA ATSUSHI "War is war and literature is literature" A Thesis Presented in Partial FulfiUment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University by Scott Charles Langton '* '* ...... The Ohio State University 1992 Master's Examination Committee: Approved by James Morita /} Richard Torrance WiUiam Tyler ~L1~~ Advise;: Department of East Asian Languages & Literatures ACKNOWLEOOMENTS I am grateful to Dr. Richard Torrance for his kind guidance and support through the course of this research. Special thanks are also due to Drs. William Tyler and James Morita for their most helpful suggestions and comments. And to my wife, Lindsay, whose patience, help and encouragement buoyed me during this project, I offer my deepest thanks. u VITA October 21. 1962 Born - Orrville. Ohio 1984 B.A.. University of California. Los Angeles. California 1986-1988 Sales Representative. Mitsui Air- International Inc.. Los Angeles, California 1989-1990 Account Executive. Kintetsu World Express Inc., Cleveland, Ohio 1990-Present Graduate Teaching Assistant. Dept. of East Asian Language and Literature. Ohio State University. Columbus, Ohio FIELDS OF STUDY Major Field: East Asian Languages and Literatures • Japanese Literature • Japanese Linguistics TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEI>GMENTS 11 VITA iii INTRODUCT ION 1 CHAPTER PAGE I. BACKGROUND AND PHILOSOPHy........................................... 9 II. LATE FICTION 49 III. "WAR IS WAR AND LITERATURE IS LITERATURE" 74 CHRONOL<XiY "............................................................................... 92 BIBLI()GRAPHY 95 lV INTRODUCTION The fiction for which Nakajima Atsushi (1909-1942) is best known was published in the early years of the Pacific War, a period coinciding with the end of his life. -

EXPERIMENTS in ART and TECHNOLOGY a Brief History and Summary of Major Projects 1966 - 1998

EXPERIMENTS IN ART AND TECHNOLOGY A Brief History and Summary of Major Projects 1966 - 1998 Experiments In Art And Technology 69 Appletree Row Berkeley Heights, NJ 07922 March 1, 1998 MAINTAIN A CONSTRUCTIVE CLIMATE FOR THE RECOGNITION OF THE NEW . TECHNOLOGY AND THE ARTS B Y A CIVILIZED COLLABORATION BETWEEN GROUPS UNREALISTICALLY DEVELOP- ING IN ISOLATION . ELIMINATE TAE SEPARATION OF THE INDIVIDUAL FROM TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE AND EKPAND AND ENRICH TECHNOLOGY TO GIVE 'II0 INDIVIDUAL VARIETY, PLEASURE AND AVENUES FOR EXPLORATION AND IN- VOLVEMENT IN CONTEMPORARY LIFE* ENCOURAGE INDUSTRIAL INITIATIVE IN GENERATING ORIGINAL FORETHOUGHT, INSTEAD OF A COMPROMISE IN AFTER- , M A T H, AND PRECIPITATE A MUTUAL AGREEMENT IN , ORDER TO AVOID THE WASTE OF A CULTURAL REVOLUTION . EXPERIMENTS IN ART AND TECHNOLOGY BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF E .A .T . in 1966 by Billy in Art and Technology was founded Experiments Fred Waldhauer, and Robert Whitman . Kluver, Robert Rauschenberg, developed the not-for-profit organization The decision to form and Engineering," the experience of "9 Evenings : Theatre from Armory in New York City in October 1966 held at the 69th Regiment artists worked .engineers and ten contemporary where''forty It became clear that if continuing together on the performances . achieved, a artist-engineer relationships were to be organic made to set up the necessary major organized effort had to be physical and social conditions . was held in New York City, November 1966, a meeting of artists . In engineers and other interested people attended by 300 artists, providing the was positive to the idea of E .A .T . The reaction . Robert Rauschenberg with access to the technical world artists president, Robert Whitman became chairman, Billy Kluver was opened to Fred Waldhauer secretary . -

Film Culture in Transition

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art ERIKA BALSOM Amsterdam University Press Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art Erika Balsom This book is published in print and online through the online OAPEN library (www.oapen.org) OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) is a collaborative in- itiative to develop and implement a sustainable Open Access publication model for academic books in the Humanities and Social Sciences. The OAPEN Library aims to improve the visibility and usability of high quality academic research by aggregating peer reviewed Open Access publications from across Europe. Sections of chapter one have previously appeared as a part of “Screening Rooms: The Movie Theatre in/and the Gallery,” in Public: Art/Culture/Ideas (), -. Sections of chapter two have previously appeared as “A Cinema in the Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins,” Screen : (December ), -. Cover illustration (front): Pierre Bismuth, Following the Right Hand of Louise Brooks in Beauty Contest, . Marker pen on Plexiglas with c-print, x inches. Courtesy of the artist and Team Gallery, New York. Cover illustration (back): Simon Starling, Wilhelm Noack oHG, . Installation view at neugerriemschneider, Berlin, . Photo: Jens Ziehe, courtesy of the artist, neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Casey Kaplan, New York. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: JAPES, Amsterdam isbn e-isbn (pdf) e-isbn (ePub) nur / © E. Balsom / Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

Aichi Triennale 2019 Has Announced the List of Additional Artists

Aichi Triennale 2019 Press Release _ Participating Artists As of March 27, 2019 Aichi Triennale 2019 Has Announced the List of Additional Artists Aichi Triennale—an international contemporary art festival that occurs once every three years and is one of the largest of its kind—has been showcasing the cutting edge of the arts since 2010, through its wide-ranging program that spans international contemporary visual art, film, the performing arts, music, and more. This fourth iteration of the festival welcomes journalist and media activist Daisuke Tsuda as its artistic director. By choosing “Taming Y/Our Passion” as the festival’s theme, Tsuda seeks to address “the sensationalization of media that at present plagues and polarizes people around the world.” He hopes that by “employing the capacity of art— a venture that, capable of encompassing every possible phenomenon, eschews framing the world through dichotomies—to speak to our compassion, thus potentially yielding clues to solving this predicament.” Aichi Triennale 2019 announced the addition of 47 artists to its lineup on 27 March 2019; the list now comprises a total of 79 artists. Outline of Aichi Triennale 2019 http://aichitriennale.jp/ Theme | Taming Y/Our Passion Artistic Director | TSUDA Daisuke (Journalist / Media Activist) Period | August 1 (Thursday) to October 14 (Monday, public holiday), 2019 [75 days] Main Venues | Aichi Arts Center; Nagoya City Art Museum; Toyota Municipal Museum of Art and off-site venues in Aichi Prefecture, JAPAN Organizer | Aichi Triennale Organizing