Nature. Vol. XI, No. 275 February 4, 1875

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAS Newsletter August 2013

www.brastro.org August 2013 Next meeting Aug 12th 7:00PM at the HRPO Dark Site Observing Dates: Primary on Aug. 3rd, Secondary on Aug. 10th Photo credit: Saturn taken on 20” OGS + Orion Starshoot - Ben Toman 1 What's in this issue: PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE....................................................................................................................3 NOTES FROM THE VICE PRESIDENT ............................................................................................4 MESSAGE FROM THE HRPO …....................................................................................................5 MONTHLY OBSERVING NOTES ....................................................................................................6 OUTREACH CHAIRPERSON’S NOTES .........................................................................................13 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION .......................................................................................................14 2 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Hi Everyone, I hope you’ve been having a great Summer so far and had luck beating the heat as much as possible. The weather sure hasn’t been cooperative for observing, though! First I have a pretty cool announcement. Thanks to the efforts of club member Walt Cooney, there are 5 newly named asteroids in the sky. (53256) Sinitiere - Named for former BRAS Treasurer Bob Sinitiere (74439) Brenden - Named for founding member Craig Brenden (85878) Guzik - Named for LSU professor T. Greg Guzik (101722) Pursell - Named for founding member Wally Pursell -

A Handbook of Double Stars, with a Catalogue of Twelve Hundred

The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924064295326 3 1924 064 295 326 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1991. HANDBOOK DOUBLE STARS. <-v6f'. — A HANDBOOK OF DOUBLE STARS, WITH A CATALOGUE OF TWELVE HUNDRED DOUBLE STARS AND EXTENSIVE LISTS OF MEASURES. With additional Notes bringing the Measures up to 1879, FOR THE USE OF AMATEURS. EDWD. CROSSLEY, F.R.A.S.; JOSEPH GLEDHILL, F.R.A.S., AND^^iMES Mt^'^I^SON, M.A., F.R.A.S. "The subject has already proved so extensive, and still ptomises so rich a harvest to those who are inclined to be diligent in the pursuit, that I cannot help inviting every lover of astronomy to join with me in observations that must inevitably lead to new discoveries." Sir Wm. Herschel. *' Stellae fixac, quae in ccelo conspiciuntur, sunt aut soles simplices, qualis sol noster, aut systemata ex binis vel interdum pluribus solibus peculiari nexu physico inter se junccis composita. -

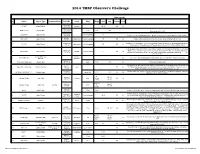

2014 Observers Challenge List

2014 TMSP Observer's Challenge Atlas page #s # Object Object Type Common Name RA, DEC Const Mag Mag.2 Size Sep. U2000 PSA 18h31m25s 1 IC 1287 Bright Nebula Scutum 20'.0 295 67 -10°47'45" 18h31m25s SAO 161569 Double Star 5.77 9.31 12.3” -10°47'45" Near center of IC 1287 18h33m28s NGC 6649 Open Cluster 8.9m Integrated 5' -10°24'10" Can be seen in 3/4d FOV with above. Brightest star is 13.2m. Approx 50 stars visible in Binos 18h28m 2 NGC 6633 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.6m integrated 27' 205 65 Visible in Binos and is about the size of a full Moon, brightest star is 7.6m +06°34' 17h46m18s 2x diameter of a full Moon. Try to view this cluster with your naked eye, binos, and a small scope. 3 IC 4665 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.2m Integrated 60' 203 65 +05º 43' Also check out “Tweedle-dee and Tweedle-dum to the east (IC 4756 and NGC 6633) A loose open cluster with a faint concentration of stars in a rich field, contains about 15-20 stars. 19h53m27s Brightest star is 9.8m, 5 stars 9-11m, remainder about 12-13m. This is a challenge obJect to 4 Harvard 20 Open Cluster Sagitta 7.7m integrated 6' 162 64 +18°19'12" improve your observation skills. Can you locate the miniature coathanger close by at 19h 37m 27s +19d? Constellation star Corona 5 Corona Borealis 55 Trace the 7 stars making up this constellation, observe and list the colors of each star asterism Borealis 15H 32' 55” Theta Corona Borealis Double Star 4.2m 6.6m .97” 55 Theta requires about 200x +31° 21' 32” The direction our Sun travels in our galaxy. -

Milan Dimitrijevic Avgust.Qxd

1. M. Platiša, M. Popović, M. Dimitrijević, N. Konjević: 1975, Z. Fur Natur- forsch. 30a, 212 [A 1].* 1. Griem, H. R.: 1975, Stark Broadening, Adv. Atom. Molec. Phys. 11, 331. 2. Platiša, M., Popović, M. V., Konjević, N.: 1975, Stark broadening of O II and O III lines, Astron. Astrophys. 45, 325. 3. Konjević, N., Wiese, W. L.: 1976, Experimental Stark widths and shifts for non-hydrogenic spectral lines of ionized atoms, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 5, 259. 4. Hey, J. D.: 1977, On the Stark broadening of isolated lines of F (II) and Cl (III) by plasmas, JQSRT 18, 649. 5. Hey, J. D.: 1977, Estimates of Stark broadening of some Ar III and Ar IV lines, JQSRT 17, 729. 6. Hey, J. D.: Breger, P.: 1980, Stark broadening of isolated lines emitted by singly - ionized tin, JQSRT 23, 311. 7. Hey, J. D.: Breger, P.: 1981, Stark broadening of isolated ion lines by plas- mas: Application of theory, in Spectral Line Shapes I, ed. B. Wende, W. de Gruyter, 201. 8. Сыркин, М. И.: 1981, Расчеты электронного уширения спектральных линий в теории оптических свойств плазмы, Опт. Спектроск. 51, 778. 9. Wiese, W. L., Konjević, N.: 1982, Regularities and similarities in plasma broadened spectral line widths (Stark widths), JQSRT 28, 185. 10. Konjević, N., Pittman, T. P.: 1986, Stark broadening of spectral lines of ho- mologous, doubly ionized inert gases, JQSRT 35, 473. 11. Konjević, N., Pittman, T. P.: 1987, Stark broadening of spectral lines of ho- mologous, doubly - ionized inert gases, JQSRT 37, 311. 12. Бабин, С. -

Binocular Double Star Logbook

Astronomical League Binocular Double Star Club Logbook 1 Table of Contents Alpha Cassiopeiae 3 14 Canis Minoris Sh 251 (Oph) Psi 1 Piscium* F Hydrae Psi 1 & 2 Draconis* 37 Ceti Iota Cancri* 10 Σ2273 (Dra) Phi Cassiopeiae 27 Hydrae 40 & 41 Draconis* 93 (Rho) & 94 Piscium Tau 1 Hydrae 67 Ophiuchi 17 Chi Ceti 35 & 36 (Zeta) Leonis 39 Draconis 56 Andromedae 4 42 Leonis Minoris Epsilon 1 & 2 Lyrae* (U) 14 Arietis Σ1474 (Hya) Zeta 1 & 2 Lyrae* 59 Andromedae Alpha Ursae Majoris 11 Beta Lyrae* 15 Trianguli Delta Leonis Delta 1 & 2 Lyrae 33 Arietis 83 Leonis Theta Serpentis* 18 19 Tauri Tau Leonis 15 Aquilae 21 & 22 Tauri 5 93 Leonis OΣΣ178 (Aql) Eta Tauri 65 Ursae Majoris 28 Aquilae Phi Tauri 67 Ursae Majoris 12 6 (Alpha) & 8 Vul 62 Tauri 12 Comae Berenices Beta Cygni* Kappa 1 & 2 Tauri 17 Comae Berenices Epsilon Sagittae 19 Theta 1 & 2 Tauri 5 (Kappa) & 6 Draconis 54 Sagittarii 57 Persei 6 32 Camelopardalis* 16 Cygni 88 Tauri Σ1740 (Vir) 57 Aquilae Sigma 1 & 2 Tauri 79 (Zeta) & 80 Ursae Maj* 13 15 Sagittae Tau Tauri 70 Virginis Theta Sagittae 62 Eridani Iota Bootis* O1 (30 & 31) Cyg* 20 Beta Camelopardalis Σ1850 (Boo) 29 Cygni 11 & 12 Camelopardalis 7 Alpha Librae* Alpha 1 & 2 Capricorni* Delta Orionis* Delta Bootis* Beta 1 & 2 Capricorni* 42 & 45 Orionis Mu 1 & 2 Bootis* 14 75 Draconis Theta 2 Orionis* Omega 1 & 2 Scorpii Rho Capricorni Gamma Leporis* Kappa Herculis Omicron Capricorni 21 35 Camelopardalis ?? Nu Scorpii S 752 (Delphinus) 5 Lyncis 8 Nu 1 & 2 Coronae Borealis 48 Cygni Nu Geminorum Rho Ophiuchi 61 Cygni* 20 Geminorum 16 & 17 Draconis* 15 5 (Gamma) & 6 Equulei Zeta Geminorum 36 & 37 Herculis 79 Cygni h 3945 (CMa) Mu 1 & 2 Scorpii Mu Cygni 22 19 Lyncis* Zeta 1 & 2 Scorpii Epsilon Pegasi* Eta Canis Majoris 9 Σ133 (Her) Pi 1 & 2 Pegasi Δ 47 (CMa) 36 Ophiuchi* 33 Pegasi 64 & 65 Geminorum Nu 1 & 2 Draconis* 16 35 Pegasi Knt 4 (Pup) 53 Ophiuchi Delta Cephei* (U) The 28 stars with asterisks are also required for the regular AL Double Star Club. -

On the Application of Stark Broadening Data Determined with a Semiclassical Perturbation Approach

Atoms 2014, 2, 357-377; doi:10.3390/atoms2030357 OPEN ACCESS atoms ISSN 2218-2004 www.mdpi.com/journal/atoms Article On the Application of Stark Broadening Data Determined with a Semiclassical Perturbation Approach Milan S. Dimitrijević 1,2,* and Sylvie Sahal-Bréchot 2 1 Astronomical Observatory, Volgina 7, 11060 Belgrade, Serbia 2 Laboratoire d'Etude du Rayonnement et de la Matière en Astrophysique, Observatoire de Paris, UMR CNRS 8112, UPMC, 5 Place Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon Cedex, France; E-Mail: [email protected] (S.S.-B.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +381-64-297-8021; Fax: +381-11-2419-553. Received: 5 May 2014; in revised form: 20 June 2014 / Accepted: 16 July 2014 / Published: 7 August 2014 Abstract: The significance of Stark broadening data for problems in astrophysics, physics, as well as for technological plasmas is discussed and applications of Stark broadening parameters calculated using a semiclassical perturbation method are analyzed. Keywords: Stark broadening; isolated lines; impact approximation 1. Introduction Stark broadening parameters of neutral atom and ion lines are of interest for a number of problems in astrophysical, laboratory, laser produced, fusion or technological plasma investigations. Especially the development of space astronomy has enabled the collection of a huge amount of spectroscopic data of all kinds of celestial objects within various spectral ranges. Consequently, the atomic data for trace elements, which had not been -

Astrophysics

Publications of the Astronomical Institute rais-mf—ii«o of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences Publication No. 70 EUROPEAN REGIONAL ASTRONOMY MEETING OF THE IA U Praha, Czechoslovakia August 24-29, 1987 ASTROPHYSICS Edited by PETR HARMANEC Proceedings, Vol. 1987 Publications of the Astronomical Institute of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences Publication No. 70 EUROPEAN REGIONAL ASTRONOMY MEETING OF THE I A U 10 Praha, Czechoslovakia August 24-29, 1987 ASTROPHYSICS Edited by PETR HARMANEC Proceedings, Vol. 5 1 987 CHIEF EDITOR OF THE PROCEEDINGS: LUBOS PEREK Astronomical Institute of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences 251 65 Ondrejov, Czechoslovakia TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface HI Invited discourse 3.-C. Pecker: Fran Tycho Brahe to Prague 1987: The Ever Changing Universe 3 lorlishdp on rapid variability of single, binary and Multiple stars A. Baglln: Time Scales and Physical Processes Involved (Review Paper) 13 Part 1 : Early-type stars P. Koubsfty: Evidence of Rapid Variability in Early-Type Stars (Review Paper) 25 NSV. Filtertdn, D.B. Gies, C.T. Bolton: The Incidence cf Absorption Line Profile Variability Among 33 the 0 Stars (Contributed Paper) R.K. Prinja, I.D. Howarth: Variability In the Stellar Wind of 68 Cygni - Not "Shells" or "Puffs", 39 but Streams (Contributed Paper) H. Hubert, B. Dagostlnoz, A.M. Hubert, M. Floquet: Short-Time Scale Variability In Some Be Stars 45 (Contributed Paper) G. talker, S. Yang, C. McDowall, G. Fahlman: Analysis of Nonradial Oscillations of Rapidly Rotating 49 Delta Scuti Stars (Contributed Paper) C. Sterken: The Variability of the Runaway Star S3 Arietis (Contributed Paper) S3 C. Blanco, A. -

1903Aj 23 . . . 22K 22 the Asteojsomic Al

22 THE ASTEOJSOMIC AL JOUENAL. Nos- 531-532 22K . Taking into account the smallness of the weights in- concerned. Through the use of these tables the positions . volved, the individual differences which make up the and motions of many stars not included in the present 23 groups in the preceding table agree^very well. catalogue can be brought into systematic harmony with it, and apparently without materially less accuracy for the in- dividual stars than could be reached by special compu- Tables of Systematic Correction for N2 and A. tations for these stars in conformity with the system of B. 1903AJ The results of the foregoing comparisons. have been This is especially true of the star-places computed by utilized to form tables of systematic corrections for ISr2, An, Dr. Auwers in the catalogues, Ai and As. As will be seen Ai and As. In right-ascension no distinction is necessary by reference to the catalogue the positions and motions of between the various catalogues published by Dr. Auwers, south polar stars taken from N2 agree better with the beginning with the Fundamental-G at alo g ; but in decli- results of this investigation than do those taken from As, nation the distinction between the northern, intermediate, which, in turn, are quoted from the Cape Catalogue for and southern catalogues must be preserved, so far as is 1890. SYSTEMATIC COBEECTIOEB : CEDEE OF DECLINATIONS. Eight-Ascensions ; Cokrections, ¿las and 100z//xtf. Declinations; Corrections, Æs and IOOzZ/x^. B — ISa B —A B —N2 B —An B —Ai âas 100 â[is âas 100 âgô âSs 100 -

![Arxiv:0709.4613V2 [Astro-Ph] 16 Apr 2008 .Quirrenbach A](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4704/arxiv-0709-4613v2-astro-ph-16-apr-2008-quirrenbach-a-2734704.webp)

Arxiv:0709.4613V2 [Astro-Ph] 16 Apr 2008 .Quirrenbach A

Astronomy and Astrophysics Review manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) M. S. Cunha · C. Aerts · J. Christensen-Dalsgaard · A. Baglin · L. Bigot · T. M. Brown · C. Catala · O. L. Creevey · A. Domiciano de Souza · P. Eggenberger · P. J. V. Garcia · F. Grundahl · P. Kervella · D. W. Kurtz · P. Mathias · A. Miglio · M. J. P. F. G. Monteiro · G. Perrin · F. P. Pijpers · D. Pourbaix · A. Quirrenbach · K. Rousselet-Perraut · T. C. Teixeira · F. Th´evenin · M. J. Thompson Asteroseismology and interferometry Received: date M. S. Cunha and T. C. Teixeira Centro de Astrof´ısica da Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762, Porto, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected] C. Aerts Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200 D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium; Afdeling Sterrenkunde, Radboud University Nijmegen, PO Box 9010, 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands. J. Christensen-Dalsgaard and F. Grundahl Institut for Fysik og Astronomi, Aarhus Universitet, Aarhus, Denmark. A. Baglin and C. Catala and P. Kervella and G. Perrin LESIA, UMR CNRS 8109, Observatoire de Paris, France. L. Bigot and F. Th´evenin Observatoire de la Cˆote d’Azur, UMR 6202, BP 4229, F-06304, Nice Cedex 4, France. T. M. Brown Las Cumbres Observatory Inc., Goleta, CA 93117, USA. arXiv:0709.4613v2 [astro-ph] 16 Apr 2008 O. L. Creevey High Altitude Observatory, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO 80301, USA; Instituto de Astrofsica de Canarias, Tenerife, E-38200, Spain. A. Domiciano de Souza Max-Planck-Institut f¨ur Radioastronomie, Auf dem H¨ugel 69, 53121 Bonn, Ger- many. P. Eggenberger Observatoire de Gen`eve, 51 chemin des Maillettes, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland; In- stitut d’Astrophysique et de G´eophysique de l’Universit´e de Li`ege All´ee du 6 Aoˆut, 17 B-4000 Li`ege, Belgium. -

An Astrometric and Spectroscopic Study of the Galactic Cluster Ngc 1039

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 69-11,654 IANNA, Philip Anthony, 1938- AN ASTROMETRIC AND SPECTROSCOPIC STUDY OF THE GALACTIC CLUSTER NGC 1039. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1968 Astronomy University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AN ASTBOXETRIC AND SPECTROSCOPIC STUDY OF THE GALACTIC CLUSTER NGC 1039 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Philip Anthony Ianna, B.A., N.A, ******* The Ohio State University 1968 Approved by Adviser Department of Astronoiqy PLEASE NOTE: Appendix pages are not original copy. Print is indistinct on many pages. Filmed in the best possible way. UNIVERSITY MICROFILMS. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to many people at a number of institutions for their kind assistance throughout this study. I would particularly like to thank try adviser. Dr. George W. Collins,11, for his encouragement and guidance over a rather long period of time. Also at The Ohio State University Drs. Walter E. Kitchell, Jr. and Arne Slettebak have given useful advice in several of the observational aspects of this work. Travel and telescope time provided by the Ohio State and Ohio Wesleyan Universities is gratefully acknowledged. The astrometric plate material was made available to me through the kind generosity of Dr. Peter van de Xamp, Director of the Sproul Observatory, and Dr. Nicholas S. Wagman, Director of the Allegheny Observatory. Other members of the staff at the Allegheny Observatory were most helpful during two observing sessions there. I am indebted to Dr. Kaj Aa. -

Information Bulletin on Variable Stars

COMMISSIONS AND OF THE I A U INFORMATION BULLETIN ON VARIABLE STARS Nos April November EDITORS L SZABADOS K OLAH TECHNICAL EDITOR A HOLL TYPESETTING MB POCS ADMINISTRATION Zs KOVARI EDITORIAL BOARD E Budding HW Duerb eck EF Guinan P Harmanec chair D Kurtz KC Leung C Maceroni NN Samus advisor C Sterken advisor H BUDAPEST XI I Box HUNGARY URL httpwwwkonkolyhuIBVSIBVShtml HU ISSN 2 IBVS 4701 { 4800 COPYRIGHT NOTICE IBVS is published on b ehalf of the th and nd Commissions of the IAU by the Konkoly Observatory Budap est Hungary Individual issues could b e downloaded for scientic and educational purp oses free of charge Bibliographic information of the recent issues could b e entered to indexing sys tems No IBVS issues may b e stored in a public retrieval system in any form or by any means electronic or otherwise without the prior written p ermission of the publishers Prior written p ermission of the publishers is required for entering IBVS issues to an electronic indexing or bibliographic system to o IBVS 4701 { 4800 3 CONTENTS WOLFGANG MOSCHNER ENRIQUE GARCIAMELENDO GSC A New Variable in the Field of V Cassiop eiae :::::::::: JM GOMEZFORRELLAD E GARCIAMELENDO J GUARROFLO J NOMENTORRES J VIDALSAINZ Observations of Selected HIPPARCOS Variables ::::::::::::::::::::::::::: JM GOMEZFORRELLAD HD a New Low Amplitude Variable Star :::::::::::::::::::::::::: ME VAN DEN ANCKER AW VOLP MR PEREZ D DE WINTER NearIR Photometry and Optical Sp ectroscopy of the Herbig Ae Star AB Au rigae ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: -

Investigating the Properties of the Near Contact Binary System TW Crb G

1 Investigating the properties of the near contact binary system TW CrB G. Faillace, C. Owen, D. Pulley & D. Smith Abstract TW Coronae Borealis (TW CrB) is a binary system likely to be active showing evidence of starspots and a hotspot. We calculated a new ephemeris based on all available timings from 1946 and find the period to be 0.58887492(2) days. We have revised the average rate of change of period down from 1.54(16) x 10-7 days yr-1 to 6.66(14) x10-8 days yr-1. Based on light curve simulation analysis we conclude that the two stars are close to filling their Roche lobes, or possibly that one of the stars’ Roche lobe has been filled. The modelling also led to a hotspot and two starspots being identified. Conservative mass transfer is one of a number of possible mechanisms considered that could explain the change in period, but the mass transfer rate would be significantly lower than previous estimates. We found evidence that suggests the period was changing in a cyclical manner, but we do not have sufficient data to make a judgement on the mechanism causing this variation. The existence of a hotspot suggests mass transfer with a corresponding increase in the amplitude in the B band as compared with the R and V bands. The chromospheric activity implied by the starspots make this binary a very likely X-ray source. Introduction Close binary systems are classified according to the shape of their combined light curve, as well as the physical and evolutionary characteristics of their components.