Arxiv:2106.09505V2 [Astro-Ph.HE] 18 Jun 2021 ★ .Amenouche M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exomoon Habitability Constrained by Illumination and Tidal Heating

submitted to Astrobiology: April 6, 2012 accepted by Astrobiology: September 8, 2012 published in Astrobiology: January 24, 2013 this updated draft: October 30, 2013 doi:10.1089/ast.2012.0859 Exomoon habitability constrained by illumination and tidal heating René HellerI , Rory BarnesII,III I Leibniz-Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP), An der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany, [email protected] II Astronomy Department, University of Washington, Box 951580, Seattle, WA 98195, [email protected] III NASA Astrobiology Institute – Virtual Planetary Laboratory Lead Team, USA Abstract The detection of moons orbiting extrasolar planets (“exomoons”) has now become feasible. Once they are discovered in the circumstellar habitable zone, questions about their habitability will emerge. Exomoons are likely to be tidally locked to their planet and hence experience days much shorter than their orbital period around the star and have seasons, all of which works in favor of habitability. These satellites can receive more illumination per area than their host planets, as the planet reflects stellar light and emits thermal photons. On the contrary, eclipses can significantly alter local climates on exomoons by reducing stellar illumination. In addition to radiative heating, tidal heating can be very large on exomoons, possibly even large enough for sterilization. We identify combinations of physical and orbital parameters for which radiative and tidal heating are strong enough to trigger a runaway greenhouse. By analogy with the circumstellar habitable zone, these constraints define a circumplanetary “habitable edge”. We apply our model to hypothetical moons around the recently discovered exoplanet Kepler-22b and the giant planet candidate KOI211.01 and describe, for the first time, the orbits of habitable exomoons. -

BRAS Newsletter August 2013

www.brastro.org August 2013 Next meeting Aug 12th 7:00PM at the HRPO Dark Site Observing Dates: Primary on Aug. 3rd, Secondary on Aug. 10th Photo credit: Saturn taken on 20” OGS + Orion Starshoot - Ben Toman 1 What's in this issue: PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE....................................................................................................................3 NOTES FROM THE VICE PRESIDENT ............................................................................................4 MESSAGE FROM THE HRPO …....................................................................................................5 MONTHLY OBSERVING NOTES ....................................................................................................6 OUTREACH CHAIRPERSON’S NOTES .........................................................................................13 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION .......................................................................................................14 2 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Hi Everyone, I hope you’ve been having a great Summer so far and had luck beating the heat as much as possible. The weather sure hasn’t been cooperative for observing, though! First I have a pretty cool announcement. Thanks to the efforts of club member Walt Cooney, there are 5 newly named asteroids in the sky. (53256) Sinitiere - Named for former BRAS Treasurer Bob Sinitiere (74439) Brenden - Named for founding member Craig Brenden (85878) Guzik - Named for LSU professor T. Greg Guzik (101722) Pursell - Named for founding member Wally Pursell -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

The Maunder Minimum and the Variable Sun-Earth Connection

The Maunder Minimum and the Variable Sun-Earth Connection (Front illustration: the Sun without spots, July 27, 1954) By Willie Wei-Hock Soon and Steven H. Yaskell To Soon Gim-Chuan, Chua Chiew-See, Pham Than (Lien+Van’s mother) and Ulla and Anna In Memory of Miriam Fuchs (baba Gil’s mother)---W.H.S. In Memory of Andrew Hoff---S.H.Y. To interrupt His Yellow Plan The Sun does not allow Caprices of the Atmosphere – And even when the Snow Heaves Balls of Specks, like Vicious Boy Directly in His Eye – Does not so much as turn His Head Busy with Majesty – ‘Tis His to stimulate the Earth And magnetize the Sea - And bind Astronomy, in place, Yet Any passing by Would deem Ourselves – the busier As the Minutest Bee That rides – emits a Thunder – A Bomb – to justify Emily Dickinson (poem 224. c. 1862) Since people are by nature poorly equipped to register any but short-term changes, it is not surprising that we fail to notice slower changes in either climate or the sun. John A. Eddy, The New Solar Physics (1977-78) Foreword By E. N. Parker In this time of global warming we are impelled by both the anticipated dire consequences and by scientific curiosity to investigate the factors that drive the climate. Climate has fluctuated strongly and abruptly in the past, with ice ages and interglacial warming as the long term extremes. Historical research in the last decades has shown short term climatic transients to be a frequent occurrence, often imposing disastrous hardship on the afflicted human populations. -

A Handbook of Double Stars, with a Catalogue of Twelve Hundred

The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924064295326 3 1924 064 295 326 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1991. HANDBOOK DOUBLE STARS. <-v6f'. — A HANDBOOK OF DOUBLE STARS, WITH A CATALOGUE OF TWELVE HUNDRED DOUBLE STARS AND EXTENSIVE LISTS OF MEASURES. With additional Notes bringing the Measures up to 1879, FOR THE USE OF AMATEURS. EDWD. CROSSLEY, F.R.A.S.; JOSEPH GLEDHILL, F.R.A.S., AND^^iMES Mt^'^I^SON, M.A., F.R.A.S. "The subject has already proved so extensive, and still ptomises so rich a harvest to those who are inclined to be diligent in the pursuit, that I cannot help inviting every lover of astronomy to join with me in observations that must inevitably lead to new discoveries." Sir Wm. Herschel. *' Stellae fixac, quae in ccelo conspiciuntur, sunt aut soles simplices, qualis sol noster, aut systemata ex binis vel interdum pluribus solibus peculiari nexu physico inter se junccis composita. -

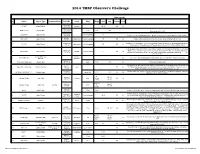

2014 Observers Challenge List

2014 TMSP Observer's Challenge Atlas page #s # Object Object Type Common Name RA, DEC Const Mag Mag.2 Size Sep. U2000 PSA 18h31m25s 1 IC 1287 Bright Nebula Scutum 20'.0 295 67 -10°47'45" 18h31m25s SAO 161569 Double Star 5.77 9.31 12.3” -10°47'45" Near center of IC 1287 18h33m28s NGC 6649 Open Cluster 8.9m Integrated 5' -10°24'10" Can be seen in 3/4d FOV with above. Brightest star is 13.2m. Approx 50 stars visible in Binos 18h28m 2 NGC 6633 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.6m integrated 27' 205 65 Visible in Binos and is about the size of a full Moon, brightest star is 7.6m +06°34' 17h46m18s 2x diameter of a full Moon. Try to view this cluster with your naked eye, binos, and a small scope. 3 IC 4665 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.2m Integrated 60' 203 65 +05º 43' Also check out “Tweedle-dee and Tweedle-dum to the east (IC 4756 and NGC 6633) A loose open cluster with a faint concentration of stars in a rich field, contains about 15-20 stars. 19h53m27s Brightest star is 9.8m, 5 stars 9-11m, remainder about 12-13m. This is a challenge obJect to 4 Harvard 20 Open Cluster Sagitta 7.7m integrated 6' 162 64 +18°19'12" improve your observation skills. Can you locate the miniature coathanger close by at 19h 37m 27s +19d? Constellation star Corona 5 Corona Borealis 55 Trace the 7 stars making up this constellation, observe and list the colors of each star asterism Borealis 15H 32' 55” Theta Corona Borealis Double Star 4.2m 6.6m .97” 55 Theta requires about 200x +31° 21' 32” The direction our Sun travels in our galaxy. -

Milan Dimitrijevic Avgust.Qxd

1. M. Platiša, M. Popović, M. Dimitrijević, N. Konjević: 1975, Z. Fur Natur- forsch. 30a, 212 [A 1].* 1. Griem, H. R.: 1975, Stark Broadening, Adv. Atom. Molec. Phys. 11, 331. 2. Platiša, M., Popović, M. V., Konjević, N.: 1975, Stark broadening of O II and O III lines, Astron. Astrophys. 45, 325. 3. Konjević, N., Wiese, W. L.: 1976, Experimental Stark widths and shifts for non-hydrogenic spectral lines of ionized atoms, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 5, 259. 4. Hey, J. D.: 1977, On the Stark broadening of isolated lines of F (II) and Cl (III) by plasmas, JQSRT 18, 649. 5. Hey, J. D.: 1977, Estimates of Stark broadening of some Ar III and Ar IV lines, JQSRT 17, 729. 6. Hey, J. D.: Breger, P.: 1980, Stark broadening of isolated lines emitted by singly - ionized tin, JQSRT 23, 311. 7. Hey, J. D.: Breger, P.: 1981, Stark broadening of isolated ion lines by plas- mas: Application of theory, in Spectral Line Shapes I, ed. B. Wende, W. de Gruyter, 201. 8. Сыркин, М. И.: 1981, Расчеты электронного уширения спектральных линий в теории оптических свойств плазмы, Опт. Спектроск. 51, 778. 9. Wiese, W. L., Konjević, N.: 1982, Regularities and similarities in plasma broadened spectral line widths (Stark widths), JQSRT 28, 185. 10. Konjević, N., Pittman, T. P.: 1986, Stark broadening of spectral lines of ho- mologous, doubly ionized inert gases, JQSRT 35, 473. 11. Konjević, N., Pittman, T. P.: 1987, Stark broadening of spectral lines of ho- mologous, doubly - ionized inert gases, JQSRT 37, 311. 12. Бабин, С. -

Binocular Double Star Logbook

Astronomical League Binocular Double Star Club Logbook 1 Table of Contents Alpha Cassiopeiae 3 14 Canis Minoris Sh 251 (Oph) Psi 1 Piscium* F Hydrae Psi 1 & 2 Draconis* 37 Ceti Iota Cancri* 10 Σ2273 (Dra) Phi Cassiopeiae 27 Hydrae 40 & 41 Draconis* 93 (Rho) & 94 Piscium Tau 1 Hydrae 67 Ophiuchi 17 Chi Ceti 35 & 36 (Zeta) Leonis 39 Draconis 56 Andromedae 4 42 Leonis Minoris Epsilon 1 & 2 Lyrae* (U) 14 Arietis Σ1474 (Hya) Zeta 1 & 2 Lyrae* 59 Andromedae Alpha Ursae Majoris 11 Beta Lyrae* 15 Trianguli Delta Leonis Delta 1 & 2 Lyrae 33 Arietis 83 Leonis Theta Serpentis* 18 19 Tauri Tau Leonis 15 Aquilae 21 & 22 Tauri 5 93 Leonis OΣΣ178 (Aql) Eta Tauri 65 Ursae Majoris 28 Aquilae Phi Tauri 67 Ursae Majoris 12 6 (Alpha) & 8 Vul 62 Tauri 12 Comae Berenices Beta Cygni* Kappa 1 & 2 Tauri 17 Comae Berenices Epsilon Sagittae 19 Theta 1 & 2 Tauri 5 (Kappa) & 6 Draconis 54 Sagittarii 57 Persei 6 32 Camelopardalis* 16 Cygni 88 Tauri Σ1740 (Vir) 57 Aquilae Sigma 1 & 2 Tauri 79 (Zeta) & 80 Ursae Maj* 13 15 Sagittae Tau Tauri 70 Virginis Theta Sagittae 62 Eridani Iota Bootis* O1 (30 & 31) Cyg* 20 Beta Camelopardalis Σ1850 (Boo) 29 Cygni 11 & 12 Camelopardalis 7 Alpha Librae* Alpha 1 & 2 Capricorni* Delta Orionis* Delta Bootis* Beta 1 & 2 Capricorni* 42 & 45 Orionis Mu 1 & 2 Bootis* 14 75 Draconis Theta 2 Orionis* Omega 1 & 2 Scorpii Rho Capricorni Gamma Leporis* Kappa Herculis Omicron Capricorni 21 35 Camelopardalis ?? Nu Scorpii S 752 (Delphinus) 5 Lyncis 8 Nu 1 & 2 Coronae Borealis 48 Cygni Nu Geminorum Rho Ophiuchi 61 Cygni* 20 Geminorum 16 & 17 Draconis* 15 5 (Gamma) & 6 Equulei Zeta Geminorum 36 & 37 Herculis 79 Cygni h 3945 (CMa) Mu 1 & 2 Scorpii Mu Cygni 22 19 Lyncis* Zeta 1 & 2 Scorpii Epsilon Pegasi* Eta Canis Majoris 9 Σ133 (Her) Pi 1 & 2 Pegasi Δ 47 (CMa) 36 Ophiuchi* 33 Pegasi 64 & 65 Geminorum Nu 1 & 2 Draconis* 16 35 Pegasi Knt 4 (Pup) 53 Ophiuchi Delta Cephei* (U) The 28 stars with asterisks are also required for the regular AL Double Star Club. -

By John Dobson San Francisco Sidewalk Astronomers

the newsletter of the QUEEN ELIZABET H PLANETARIUM SUMMER 198 0 and the EDMONTON CENTRE, RAS C 50$ y SPECIAL TELESCOP E ISSU E NOW PLAYIN G AT QUEEN PlANETARiUM A spectacular celestial event was witnessed by th e ancien t Sumeria n civilizatio n an d ""VELA recorded i n thei r mysteriou s cuneifor m writing. Wha t wa s it ? Th e Vela Apparition APPARITION blends archaeolog y wit h astronom y i n a search for the origins o f civilzation. 3 P M and 8 P M Daily one The night sk y i s a fascinating -realm. Stars, nebulae, an d galaxie s ar e scattere d SUMMER'S throughout infinity . Join us for a tour of the sights o f th e summertim e sky . Rela x and NIGHT enjoy an evening at the Planetarium durin g One Summer's Night. 9PM Dail y A special show for special people age 3 to 7. A Fantasy O f Stars chronicle s th e FANTASY adventures o f Harol d th e Her o a s h e ventures int o th e nigh t sk y t o mee t th e constellations. A reduced admission of only o, STARS 50C for everyon e applies to thi s 3 5 minute live presentation. For more •information , „ , please phone th re Planetariu•• , , 1:3m at 0 P M Wed . and Sun . 455-0119 Vol. 2 5 No . 1 0 StOPCll SUMMER 198 0 Have Telescopes , Will Travel JOH N DOBSO N 1 0 People came from all over the city by bus, by car, by bicycle, and by foot to look through the telescope. -

Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c81z4932 Online items available Lick Observatory Records: Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Kate Dundon, Alix Norton, Maureen Carey, Christine Turk, Alex Moore University of California, Santa Cruz 2016 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Lick Observatory Records: UA.036.Ser.07 1 Photographs UA.036.Ser.07 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Lick Observatory Records: Photographs Creator: Lick Observatory Identifier/Call Number: UA.036.Ser.07 Physical Description: 101.62 Linear Feet127 boxes Date (inclusive): circa 1870-2002 Language of Material: English . https://n2t.net/ark:/38305/f19c6wg4 Conditions Governing Access Collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Lick Observatory Records: Photographs. UA36 Ser.7. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Alternative Format Available Images from this collection are available through UCSC Library Digital Collections. Historical note These photographs were produced or collected by Lick observatory staff and faculty, as well as UCSC Library personnel. Many of the early photographs of the major instruments and Observatory buildings were taken by Henry E. Matthews, who served as secretary to the Lick Trust during the planning and construction of the Observatory. -

Using Asteroseismology to Characterise Exoplanet Host Stars

Using asteroseismology to characterise exoplanet host stars Mia S. Lundkvist, Daniel Huber, Victor Silva Aguirre, and William J. Chaplin Abstract The last decade has seen a revolution in the field of asteroseismology – the study of stellar pulsations. It has become a powerful method to precisely characterise exoplanet host stars, and as a consequence also the exoplanets themselves. This syn- ergy between asteroseismology and exoplanet science has flourished in large part due to space missions such as Kepler, which have provided high-quality data that can be used for both types of studies. Perhaps the primary contribution from aster- oseismology to the research on transiting exoplanets is the determination of very precise stellar radii that translate into precise planetary radii, but asteroseismology has also proven useful in constraining eccentricities of exoplanets as well as the dy- namical architecture of planetary systems. In this chapter, we introduce some basic principles of asteroseismology and review current synergies between the two fields. Mia S. Lundkvist Zentrum fur¨ Astronomie der Universitat¨ Heidelberg, Landessternwarte, Konigstuhl¨ 12, 69117 Hei- delberg, DE, and Stellar Astrophysics Centre, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 120, 8000 Aarhus C, DK, e-mail: [email protected] Daniel Huber Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai‘i, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, US and Sydney Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Aus- tralia, e-mail: [email protected] Victor Silva Aguirre arXiv:1804.02214v2 [astro-ph.SR] 9 Apr 2018 Stellar Astrophysics Centre, Aarhus University, Ny Munkegade 120, 8000 Aarhus C, DK, e-mail: [email protected] William J. -

![Arxiv:2006.10868V2 [Astro-Ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut D’Estudis Espacials De Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`A2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3592/arxiv-2006-10868v2-astro-ph-sr-9-apr-2021-spain-and-institut-d-estudis-espacials-de-catalunya-ieec-c-gran-capit-a2-4-e-08034-2-serenelli-weiss-aerts-et-al-1213592.webp)

Arxiv:2006.10868V2 [Astro-Ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut D’Estudis Espacials De Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`A2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts Et Al

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Weighing stars from birth to death: mass determination methods across the HRD Aldo Serenelli · Achim Weiss · Conny Aerts · George C. Angelou · David Baroch · Nate Bastian · Paul G. Beck · Maria Bergemann · Joachim M. Bestenlehner · Ian Czekala · Nancy Elias-Rosa · Ana Escorza · Vincent Van Eylen · Diane K. Feuillet · Davide Gandolfi · Mark Gieles · L´eoGirardi · Yveline Lebreton · Nicolas Lodieu · Marie Martig · Marcelo M. Miller Bertolami · Joey S.G. Mombarg · Juan Carlos Morales · Andr´esMoya · Benard Nsamba · KreˇsimirPavlovski · May G. Pedersen · Ignasi Ribas · Fabian R.N. Schneider · Victor Silva Aguirre · Keivan G. Stassun · Eline Tolstoy · Pier-Emmanuel Tremblay · Konstanze Zwintz Received: date / Accepted: date A. Serenelli Institute of Space Sciences (ICE, CSIC), Carrer de Can Magrans S/N, Bellaterra, E- 08193, Spain and Institut d'Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), Carrer Gran Capita 2, Barcelona, E-08034, Spain E-mail: [email protected] A. Weiss Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl Schwarzschild Str. 1, Garching bei M¨unchen, D-85741, Germany C. Aerts Institute of Astronomy, Department of Physics & Astronomy, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200 D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium and Department of Astrophysics, IMAPP, Radboud University Nijmegen, Heyendaalseweg 135, 6525 AJ Nijmegen, the Netherlands G.C. Angelou Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl Schwarzschild Str. 1, Garching bei M¨unchen, D-85741, Germany D. Baroch J. C. Morales I. Ribas Institute of· Space Sciences· (ICE, CSIC), Carrer de Can Magrans S/N, Bellaterra, E-08193, arXiv:2006.10868v2 [astro-ph.SR] 9 Apr 2021 Spain and Institut d'Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC), C/Gran Capit`a2-4, E-08034 2 Serenelli, Weiss, Aerts et al.