Arxiv:0709.4613V2 [Astro-Ph] 16 Apr 2008 .Quirrenbach A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAS Newsletter August 2013

www.brastro.org August 2013 Next meeting Aug 12th 7:00PM at the HRPO Dark Site Observing Dates: Primary on Aug. 3rd, Secondary on Aug. 10th Photo credit: Saturn taken on 20” OGS + Orion Starshoot - Ben Toman 1 What's in this issue: PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE....................................................................................................................3 NOTES FROM THE VICE PRESIDENT ............................................................................................4 MESSAGE FROM THE HRPO …....................................................................................................5 MONTHLY OBSERVING NOTES ....................................................................................................6 OUTREACH CHAIRPERSON’S NOTES .........................................................................................13 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION .......................................................................................................14 2 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Hi Everyone, I hope you’ve been having a great Summer so far and had luck beating the heat as much as possible. The weather sure hasn’t been cooperative for observing, though! First I have a pretty cool announcement. Thanks to the efforts of club member Walt Cooney, there are 5 newly named asteroids in the sky. (53256) Sinitiere - Named for former BRAS Treasurer Bob Sinitiere (74439) Brenden - Named for founding member Craig Brenden (85878) Guzik - Named for LSU professor T. Greg Guzik (101722) Pursell - Named for founding member Wally Pursell -

Central Coast Astronomy Virtual Star Party May 15Th 7Pm Pacific

Central Coast Astronomy Virtual Star Party May 15th 7pm Pacific Welcome to our Virtual Star Gazing session! We’ll be focusing on objects you can see with binoculars or a small telescope, so after our session, you can simply walk outside, look up, and understand what you’re looking at. CCAS President Aurora Lipper and astronomer Kent Wallace will bring you a virtual “tour of the night sky” where you can discover, learn, and ask questions as we go along! All you need is an internet connection. You can use an iPad, laptop, computer or cell phone. When 7pm on Saturday night rolls around, click the link on our website to join our class. CentralCoastAstronomy.org/stargaze Before our session starts: Step 1: Download your free map of the night sky: SkyMaps.com They have it available for Northern and Southern hemispheres. Step 2: Print out this document and use it to take notes during our time on Saturday. This document highlights the objects we will focus on in our session together. Celestial Objects: Moon: The moon 4 days after new, which is excellent for star gazing! *Image credit: all astrophotography images are courtesy of NASA & ESO unless otherwise noted. All planetarium images are courtesy of Stellarium. Central Coast Astronomy CentralCoastAstronomy.org Page 1 Main Focus for the Session: 1. Canes Venatici (The Hunting Dogs) 2. Boötes (the Herdsman) 3. Coma Berenices (Hair of Berenice) 4. Virgo (the Virgin) Central Coast Astronomy CentralCoastAstronomy.org Page 2 Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs) Canes Venatici, The Hunting Dogs, a modern constellation created by Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius in 1687. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses First visibility of the lunar crescent and other problems in historical astronomy. Fatoohi, Louay J. How to cite: Fatoohi, Louay J. (1998) First visibility of the lunar crescent and other problems in historical astronomy., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/996/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk me91 In the name of Allah, the Gracious, the Merciful >° 9 43'' 0' eji e' e e> igo4 U61 J CO J: lic 6..ý v Lo ý , ý.,, "ý J ýs ýºý. ur ý,r11 Lýi is' ý9r ZU LZJE rju No disaster can befall on the earth or in your souls but it is in a book before We bring it into being; that is easy for Allah. In order that you may not grieve for what has escaped you, nor be exultant at what He has given you; and Allah does not love any prideful boaster. -

Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Second Edition

RASC Observing Committee Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Second Edition Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Welcome to the Explore the Universe Observing Certificate Program. This program is designed to provide the observer with a well-rounded introduction to the night sky visible from North America. Using this observing program is an excellent way to gain knowledge and experience in astronomy. Experienced observers find that a planned observing session results in a more satisfying and interesting experience. This program will help introduce you to amateur astronomy and prepare you for other more challenging certificate programs such as the Messier and Finest NGC. The program covers the full range of astronomical objects. Here is a summary: Observing Objective Requirement Available Constellations and Bright Stars 12 24 The Moon 16 32 Solar System 5 10 Deep Sky Objects 12 24 Double Stars 10 20 Total 55 110 In each category a choice of objects is provided so that you can begin the certificate at any time of the year. In order to receive your certificate you need to observe a total of 55 of the 110 objects available. Here is a summary of some of the abbreviations used in this program Instrument V – Visual (unaided eye) B – Binocular T – Telescope V/B - Visual/Binocular B/T - Binocular/Telescope Season Season when the object can be best seen in the evening sky between dusk. and midnight. Objects may also be seen in other seasons. Description Brief description of the target object, its common name and other details. Cons Constellation where object can be found (if applicable) BOG Ref Refers to corresponding references in the RASC’s The Beginner’s Observing Guide highlighting this object. -

Multiple Star Systems Observed with Corot and Kepler

Multiple star systems observed with CoRoT and Kepler John Southworth Astrophysics Group, Keele University, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK Abstract. The CoRoT and Kepler satellites were the first space platforms designed to perform high-precision photometry for a large number of stars. Multiple systems dis- play a wide variety of photometric variability, making them natural benefactors of these missions. I review the work arising from CoRoT and Kepler observations of multiple sys- tems, with particular emphasis on eclipsing binaries containing giant stars, pulsators, triple eclipses and/or low-mass stars. Many more results remain untapped in the data archives of these missions, and the future holds the promise of K2, TESS and PLATO. 1 Introduction The CoRoT and Kepler satellites represent the first generation of astronomical space missions capable of large-scale photometric surveys. The large quantity – and exquisite quality – of the data they pro- vided is in the process of revolutionising stellar and planetary astrophysics. In this review I highlight the immense variety of the scientific results from these concurrent missions, as well as the context provided by their precursors and implications for their successors. CoRoT was led by CNES and ESA, launched on 2006/12/27,and retired in June 2013 after an irre- trievable computer failure in November 2012. It performed 24 observing runs, each lasting between 21 and 152days, with a field of viewof 2×1.3◦ ×1.3◦, obtaining light curves of 163000 stars [42]. Kepler was a NASA mission, launched on 2009/03/07and suffering a critical pointing failure on 2013/05/11. It observed the same 105deg2 sky area for its full mission duration, obtaining high-precision light curves of approximately 191000 stars. -

February 2014 BRAS Newsletter

February, 2014 Next Meeting February 10th 7PM at the HRPO Self Portrait of Mars Rover Opportunity: 10 years and still going! What's In This Issue? President's Message Vice-President's Message Secretary's Summary Message from HRPO Globe at Night 20/20 Vision Imagine Your Parks Recent Forum Posts President's Message Well, the Nordic ice giants have moved into the state and have settled in for a while. By the time you get this we will have gone through at least two episodes of wet icy sub- freezing weather fronts. We sorry Louisianans just are not used to this stuff. Thankfully, the skies are crystal clear afterwards. They aren’t always the best for planetary work, with the high atmospheric turbulence that often follows a front, but it is a good time for deep sky work. The skies provide a much higher contrast that allows us to see those fine low-contrast details that are often so hard to pull out in these climes. There is a supernova visible in the edge-on galaxy M82, in Ursa Major. As I write this, it is visible in scopes around 8 inches aperture and up, and easily photographed. Be sure to take a look. It is not every day we get a supernova so bright. During our last meeting, we took a vote on what item we BRAS members would like most as our next big ticket raffle prize. The Coronado PST won. They are much more affordable now, sometimes selling for as little as $650. We are shopping around for the best deal now. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

A Handbook of Double Stars, with a Catalogue of Twelve Hundred

The original of this bool< is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924064295326 3 1924 064 295 326 Production Note Cornell University Library pro- duced this volume to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. It was scanned using Xerox soft- ware and equipment at 600 dots per inch resolution and com- pressed prior to storage using CCITT Group 4 compression. The digital data were used to create Cornell's replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Stand- ard Z39. 48-1984. The production of this volume was supported in part by the Commission on Pres- ervation and Access and the Xerox Corporation. Digital file copy- right by Cornell University Library 1991. HANDBOOK DOUBLE STARS. <-v6f'. — A HANDBOOK OF DOUBLE STARS, WITH A CATALOGUE OF TWELVE HUNDRED DOUBLE STARS AND EXTENSIVE LISTS OF MEASURES. With additional Notes bringing the Measures up to 1879, FOR THE USE OF AMATEURS. EDWD. CROSSLEY, F.R.A.S.; JOSEPH GLEDHILL, F.R.A.S., AND^^iMES Mt^'^I^SON, M.A., F.R.A.S. "The subject has already proved so extensive, and still ptomises so rich a harvest to those who are inclined to be diligent in the pursuit, that I cannot help inviting every lover of astronomy to join with me in observations that must inevitably lead to new discoveries." Sir Wm. Herschel. *' Stellae fixac, quae in ccelo conspiciuntur, sunt aut soles simplices, qualis sol noster, aut systemata ex binis vel interdum pluribus solibus peculiari nexu physico inter se junccis composita. -

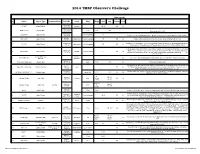

2014 Observers Challenge List

2014 TMSP Observer's Challenge Atlas page #s # Object Object Type Common Name RA, DEC Const Mag Mag.2 Size Sep. U2000 PSA 18h31m25s 1 IC 1287 Bright Nebula Scutum 20'.0 295 67 -10°47'45" 18h31m25s SAO 161569 Double Star 5.77 9.31 12.3” -10°47'45" Near center of IC 1287 18h33m28s NGC 6649 Open Cluster 8.9m Integrated 5' -10°24'10" Can be seen in 3/4d FOV with above. Brightest star is 13.2m. Approx 50 stars visible in Binos 18h28m 2 NGC 6633 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.6m integrated 27' 205 65 Visible in Binos and is about the size of a full Moon, brightest star is 7.6m +06°34' 17h46m18s 2x diameter of a full Moon. Try to view this cluster with your naked eye, binos, and a small scope. 3 IC 4665 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.2m Integrated 60' 203 65 +05º 43' Also check out “Tweedle-dee and Tweedle-dum to the east (IC 4756 and NGC 6633) A loose open cluster with a faint concentration of stars in a rich field, contains about 15-20 stars. 19h53m27s Brightest star is 9.8m, 5 stars 9-11m, remainder about 12-13m. This is a challenge obJect to 4 Harvard 20 Open Cluster Sagitta 7.7m integrated 6' 162 64 +18°19'12" improve your observation skills. Can you locate the miniature coathanger close by at 19h 37m 27s +19d? Constellation star Corona 5 Corona Borealis 55 Trace the 7 stars making up this constellation, observe and list the colors of each star asterism Borealis 15H 32' 55” Theta Corona Borealis Double Star 4.2m 6.6m .97” 55 Theta requires about 200x +31° 21' 32” The direction our Sun travels in our galaxy. -

Milan Dimitrijevic Avgust.Qxd

1. M. Platiša, M. Popović, M. Dimitrijević, N. Konjević: 1975, Z. Fur Natur- forsch. 30a, 212 [A 1].* 1. Griem, H. R.: 1975, Stark Broadening, Adv. Atom. Molec. Phys. 11, 331. 2. Platiša, M., Popović, M. V., Konjević, N.: 1975, Stark broadening of O II and O III lines, Astron. Astrophys. 45, 325. 3. Konjević, N., Wiese, W. L.: 1976, Experimental Stark widths and shifts for non-hydrogenic spectral lines of ionized atoms, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 5, 259. 4. Hey, J. D.: 1977, On the Stark broadening of isolated lines of F (II) and Cl (III) by plasmas, JQSRT 18, 649. 5. Hey, J. D.: 1977, Estimates of Stark broadening of some Ar III and Ar IV lines, JQSRT 17, 729. 6. Hey, J. D.: Breger, P.: 1980, Stark broadening of isolated lines emitted by singly - ionized tin, JQSRT 23, 311. 7. Hey, J. D.: Breger, P.: 1981, Stark broadening of isolated ion lines by plas- mas: Application of theory, in Spectral Line Shapes I, ed. B. Wende, W. de Gruyter, 201. 8. Сыркин, М. И.: 1981, Расчеты электронного уширения спектральных линий в теории оптических свойств плазмы, Опт. Спектроск. 51, 778. 9. Wiese, W. L., Konjević, N.: 1982, Regularities and similarities in plasma broadened spectral line widths (Stark widths), JQSRT 28, 185. 10. Konjević, N., Pittman, T. P.: 1986, Stark broadening of spectral lines of ho- mologous, doubly ionized inert gases, JQSRT 35, 473. 11. Konjević, N., Pittman, T. P.: 1987, Stark broadening of spectral lines of ho- mologous, doubly - ionized inert gases, JQSRT 37, 311. 12. Бабин, С. -

Binocular Double Star Logbook

Astronomical League Binocular Double Star Club Logbook 1 Table of Contents Alpha Cassiopeiae 3 14 Canis Minoris Sh 251 (Oph) Psi 1 Piscium* F Hydrae Psi 1 & 2 Draconis* 37 Ceti Iota Cancri* 10 Σ2273 (Dra) Phi Cassiopeiae 27 Hydrae 40 & 41 Draconis* 93 (Rho) & 94 Piscium Tau 1 Hydrae 67 Ophiuchi 17 Chi Ceti 35 & 36 (Zeta) Leonis 39 Draconis 56 Andromedae 4 42 Leonis Minoris Epsilon 1 & 2 Lyrae* (U) 14 Arietis Σ1474 (Hya) Zeta 1 & 2 Lyrae* 59 Andromedae Alpha Ursae Majoris 11 Beta Lyrae* 15 Trianguli Delta Leonis Delta 1 & 2 Lyrae 33 Arietis 83 Leonis Theta Serpentis* 18 19 Tauri Tau Leonis 15 Aquilae 21 & 22 Tauri 5 93 Leonis OΣΣ178 (Aql) Eta Tauri 65 Ursae Majoris 28 Aquilae Phi Tauri 67 Ursae Majoris 12 6 (Alpha) & 8 Vul 62 Tauri 12 Comae Berenices Beta Cygni* Kappa 1 & 2 Tauri 17 Comae Berenices Epsilon Sagittae 19 Theta 1 & 2 Tauri 5 (Kappa) & 6 Draconis 54 Sagittarii 57 Persei 6 32 Camelopardalis* 16 Cygni 88 Tauri Σ1740 (Vir) 57 Aquilae Sigma 1 & 2 Tauri 79 (Zeta) & 80 Ursae Maj* 13 15 Sagittae Tau Tauri 70 Virginis Theta Sagittae 62 Eridani Iota Bootis* O1 (30 & 31) Cyg* 20 Beta Camelopardalis Σ1850 (Boo) 29 Cygni 11 & 12 Camelopardalis 7 Alpha Librae* Alpha 1 & 2 Capricorni* Delta Orionis* Delta Bootis* Beta 1 & 2 Capricorni* 42 & 45 Orionis Mu 1 & 2 Bootis* 14 75 Draconis Theta 2 Orionis* Omega 1 & 2 Scorpii Rho Capricorni Gamma Leporis* Kappa Herculis Omicron Capricorni 21 35 Camelopardalis ?? Nu Scorpii S 752 (Delphinus) 5 Lyncis 8 Nu 1 & 2 Coronae Borealis 48 Cygni Nu Geminorum Rho Ophiuchi 61 Cygni* 20 Geminorum 16 & 17 Draconis* 15 5 (Gamma) & 6 Equulei Zeta Geminorum 36 & 37 Herculis 79 Cygni h 3945 (CMa) Mu 1 & 2 Scorpii Mu Cygni 22 19 Lyncis* Zeta 1 & 2 Scorpii Epsilon Pegasi* Eta Canis Majoris 9 Σ133 (Her) Pi 1 & 2 Pegasi Δ 47 (CMa) 36 Ophiuchi* 33 Pegasi 64 & 65 Geminorum Nu 1 & 2 Draconis* 16 35 Pegasi Knt 4 (Pup) 53 Ophiuchi Delta Cephei* (U) The 28 stars with asterisks are also required for the regular AL Double Star Club. -

Sodium and Potassium Signatures Of

Sodium and Potassium Signatures of Volcanic Satellites Orbiting Close-in Gas Giant Exoplanets Apurva Oza, Robert Johnson, Emmanuel Lellouch, Carl Schmidt, Nick Schneider, Chenliang Huang, Diana Gamborino, Andrea Gebek, Aurelien Wyttenbach, Brice-Olivier Demory, et al. To cite this version: Apurva Oza, Robert Johnson, Emmanuel Lellouch, Carl Schmidt, Nick Schneider, et al.. Sodium and Potassium Signatures of Volcanic Satellites Orbiting Close-in Gas Giant Exoplanets. The Astro- physical Journal, American Astronomical Society, 2019, 885 (2), pp.168. 10.3847/1538-4357/ab40cc. hal-02417964 HAL Id: hal-02417964 https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-02417964 Submitted on 18 Dec 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Astrophysical Journal, 885:168 (19pp), 2019 November 10 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ab40cc © 2019. The American Astronomical Society. Sodium and Potassium Signatures of Volcanic Satellites Orbiting Close-in Gas Giant Exoplanets Apurva V. Oza1 , Robert E. Johnson2,3 , Emmanuel Lellouch4 , Carl Schmidt5 , Nick Schneider6 , Chenliang Huang7 , Diana Gamborino1 , Andrea Gebek1,8 , Aurelien Wyttenbach9 , Brice-Olivier Demory10 , Christoph Mordasini1 , Prabal Saxena11, David Dubois12 , Arielle Moullet12, and Nicolas Thomas1 1 Physikalisches Institut, Universität Bern, Bern, Switzerland; [email protected] 2 Engineering Physics, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA 22903, USA 3 Physics, New York University, 4 Washington Place, New York, NY 10003, USA 4 LESIA–Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC Univ.