Download (1717Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Andthe Anarchists Other Issues of "Anarchy"L Gontents of Il0

AilARCHYJ{0.109 3shillings lSpence 40cents "-*"*"'"'r ,Eh$ Russell andthe Anarchists Other issues of "Anarchy"l Gontents of il0. 109 Please note that the following issues are out of print: I to 15 inclusive, 26,27, 38, ANiARCHY 109 (Vol l0 No 3) MARCH 1970 65 March 1970 39, 66, 89, 90, 96, 98, 102. Vol. I 1961l. 1. Sex-and-Violence; 2. Workers' control; 3. What does anar- chism mcarr today?: 4. Deinstitutioni- sariorr; 5. Spain; 6. Cinema; 7. Adventure playgrourrd; 3. Anthropology; 9. Prison; 10. [ndustrial decentralisation. Neither God nor Master V. Ncill; 12. Who are the anarchists?; 13. Richard Drinnon 65 Direct action; 14. Disobcdience; 15. David Wills; 16. Ethics of anarchism; 17. Lum- lleilther God pcn proletariat ; I {l.Comprehensive schools; Russell and the anarchists 19. 'Ihcatrc; 20. Non-violence; 21. Secon- dary Vivian Harper 68 modern; 22. Marx and Bakunin. nor Master Vol. 3. l96f : 23. Squatters; 24. Com- murrity of scholars; 25. Cybernetics; 26. RIOHABD DNIililOI{ Counter-culture 'l'horcarri 27. Yor-rth; 28. Future of anar- chisml 2t). Spies for peace;30. Com- Kingsley lAidmer 18 rnurrity workshop; 31. Self-organising systcmsi 32. Orimc; 33. Alex Comfort; Kropotkin and his memoirs J4. Scicnce fiction. Nicolas Walter 84 .17. I won't votc; 38. Nottingham; 39. Tsoucn ITS Roors ARE DBEpLy BURIED, modern anarchism I Iorncr l-ancl 40. Unions; 41. Land; dates from the entry of the Bakuninists into the First Inter- 42. India; 43. Parents and teachers; 44, Observations on eNanttnv 104 l'rarrsport; 45. Thc Greeks;46. Anarchisrn national just a hundred years ago. -

Memories on a Monday: Peace Monday 11 May 2020

Memories on a Monday: Peace Monday 11 May 2020 Welcome to Memories on a Monday: Peace - sharing our heritage from Bruce Castle Museum & Archive. Following the commemorative events last week of VE Day, we turn now to looking at some of the ways we have marked peace in our communities in Haringey, alongside the strong heritage of the peace movement and activism in the borough. In July 2014, a memorial was unveiled alongside the woodland in Lordship Recreation Ground in Tottenham. Created by local sculptor Gary March, the sculpture shows two hands embracing a dove, the symbol of peace. Its design and installation followed a successful a campaign initiated by Ray Swain and the Friends of Lordship Rec to dedicate a permanent memorial to over 40 local people who tragically lost their lives in September 1940. They died following a direct hit by a high-explosive bomb falling on the Downhills public air raid shelter. It was the highest death toll in Tottenham during the Second World War. (You can see the sculpture and read more about this tragedy here and also here from the Summerhill Road website). Three years before, in Stroud Green, a Peace Garden was named and unveiled in 2011. It commemorates the 15 people who died, 35 people who were seriously injured, the destruction of 12 houses and the severe damage of Holy Trinity Church and 100 other homes in the area. The details below, can be read on the attached PDF. The Peace Garden Board can be found in the garden, at the junction where Stapleton Hall Road meets Granville Road, N4. -

Quaker Thought and Life Today

Quaker Thought and Life Today VOWMI 9 JULY 15, 1963 NUMBER 14 C!)f: puff and wheeze, we struggle and discuss. We have A Meeting's Creative Experience endless committee meetings. But j esus said where two or A Committee's Report three meet in my name I am there in the midst, and then they grow like the lily or the tree by the brook. I t isn't Letter from England effort, it isn't struggle that makes persons grow. It is life. by Colin Fawcett It is contact with the forces of life that does it. Growth is silent, gentle, quiet, unnoticed, but you can't have growth un Good Words for Love's Fools til you have the miracle of life and until it is in contact with by Sam Bradley the sources and the forces of life-soil, sun, water, and air. - R uFus M. JoNEs 1863 Bright-Churchill 1963 A Letter from the Past TWENTY· FIVE CENTS $5.00 A YEAR Under the Red and Black Star 306 FRIENDS JOURNAL July 15, 1963 FRIENDS JOURNAL UNDER THE RED AND BLACK STAR AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Lahsin Plants a Tree ORMALLY on Thursday afternoons Lahsin Hajar, N a 10-year-old Algerian boy, can be found in the carpentry workshop of the Quaker Center at Souk el Tleta, working on a bench he is making. Today, however, Published semimonthly, on the first and fifteenth of each month, at 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 2, Penn he has been picked by the Quaker agriculturalist to sYlvania (LO 3-7669) by Friends Publishing Corporation. -

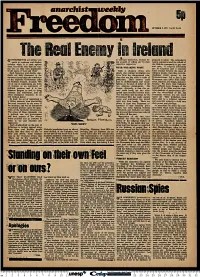

Standing on Their Own Feet Or on Ours?

anarchistmmweehly Vol 32 No 31 riOVERNMENTS are always very to extricate themselves, without be- prepared to admit. The campaign is quick to condemn and deplore ing accused of 'selling out' by their mainly centred around the refusal of ' violence when it is used against respective supporters. the Catholic community to pay rent them, but all the time they are wag- *2? and rates. If religious differences ing war on their own populations NEAR BREAKING POINT can be forgotten and a common in the name of 'Law and Order'. Such a situation shows \pry bond created between the mass of Such hypocrisy and double stan- clearly that nothing worthwhile can ordinary people, then this civil dis- dards are fully illustrated in the come from the compromised solu- obedience could spread to the statement issued after the conclusion tions that are the stock in trade of Protestant areas. Let us face it, the of the tripartite Government talks politicians. Their answers could Protestants also suffer from indig- on Northern Ireland. It reads: 'We lead to disillusionment and resent- nities, injustice, low wages, and poor are at one in condemning any form *SpV '■"■ t •■■■•.-•>a*-v.tv13fc:V-J~. ■ '. ¥r \£-\. ■':'<*.^^!.^/'Ui/^jKjp,-ki,f-^AJi^ fulness on the part of either of the . housing. We know that Catholics of violence as an instrument of il'*;(»»'>,i,^'lk"'f-l<*. -»fr''^ . Vt'/i'li'/-- 1 '' '*■ ■''■**4fflv- ■ ' V'^&f«Ufl*?tivr r two religious communities. The have suffered more because of the political pressure and it is our danger, obviously, is that this en- inability of the State and the capi- common purpose to seek to bring mity could break out into wide- talist methods of production to pro- violence and internment, and all spread open hostility between them. -

The British Far Left from 1956

The British far left from 1956 EDITED BY EVAN SMITH AND MATTHEW WORLEY Against the grain MANCHESTER 1824 Manchester University Press This content downloaded from 154.59.124.115 on Sun, 11 Feb 2018 10:26:06 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms This content downloaded from 154.59.124.115 on Sun, 11 Feb 2018 10:26:06 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Against the grain The British far left from 1956 Edited by Evan Smith and Matthew Worley Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed in the United States exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan This content downloaded from 154.59.124.115 on Sun, 11 Feb 2018 10:26:06 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Copyright © Manchester University Press 2014 While copyright in the volume as a whole is vested in Manchester University Press, copyright in individual chapters belongs to their respective authors, and no chapter may be reproduced wholly or in part without the express permission in writing of both author and publisher. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed in the United States exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed in Canada exclusively by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 978 07190 9590 0 hardback First published 2014 The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. -

Anarchists and the Peace Movement

' rm =|__ K -.'. 1:;-' iv”:r . ' ._' -. -.w- -to Eric Harrison 1922-1993 Eric Harrison died on the 19th Decem- 50p ber 1993 after a short illness. In his I w later years he suffered from arthritis °0\-.1-. --1 which affected his walking ability. He leaves a daughter, Deborah, and six grand-children. ‘A Eric was a natural Pacifist and one of . 4 Anarchis_ ts er“ the most gentle men I have known. He - - .- -. .-I ~-,-,-*- -1° c,- ' "-‘I’ . 43 ~, '5-. ,, _ _ ,-"J". left school at 14 and trained as a tool- I I. .? F l‘ .‘f -L‘-K 'Q_ 0‘ I I, . .-:Q4L"-'_-_\.q I. ;H20‘; '115 .-*3!‘ur ‘.5 - 2-'-‘, ‘I... 'f .I. &‘ -' , . _ Ifrl., 0 __ maker with the Daimler motor oom- ' ,1,‘ . ‘ 1 '1-.____‘_~ .6 ‘E ._‘\..€ 4‘. P _ 9 _ i . 9- \ I. _" " 7- - .‘ - '7,_ _ Q I, pany. He became a shop steward ‘I _ _-_ _‘ ,1 t _ i. _ ' ‘-Q n ' Q; ._ - l Q‘if\l- F.... \§ ".9 '0F.’|. I "1:-‘rm20- active in the Trade Union movement. I ' I‘ p. ;- it Q . _ ' Qt’ " , -5- . ' III . - n ' . -' . first met him in Coventry when I was _.~v\'-13I ‘l_ $ there with the Film Van in 1963; he be- came a very keen supporter and in his ‘on later life became a Trustee with us -a and the v- ,o.o,;s-..'— | - here at the Brotherhood. During the l. ._?. I‘ ¢- : "‘ ., . ~ ' l J 5‘ 4'. : * " l sixties he was active with the Commit- sf "=" -c,;f+"I.-.e:5::§ 1 _\ ‘ e I . -

Fill the Jails': Identity, Structure and Method in the Committee of 100, 1960 – 1968

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 'Fill the Jails': Identity, Structure and Method in the Committee of 100, 1960 – 1968. Thesis submitted by Samantha Jane Carroll D. Phil. in Life History Research University of Sussex September 2010 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:........................................... Contents. Summary. Acknowledgements. Introduction. 1 Chapter One: Methodology. 29 Chapter Two: Middle-Class Radicals? Make-up and Motivations. 67 Chapter Three: Non-Violent Direct Action. A Contentious Issue. 98 Chapter Four: 'Fill the Jails'. Committee of 100 in Action. 122 Chapter Five: Imprisonment. Gender, Class and Entitlement. 158 Chapter Six: A Libertarian Spirit? Organisation and Values. 182 Conclusion. 213 Bibliography. 222 Appendices. 232 UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX D.PHIL. IN LIFE HISTORY RESEARCH 'FILL THE JAILS': IDENTITY, STRUCTURE AND METHOD IN THE COMMITTEE OF 100, 1960 – 1968. SUMMARY The Committee of 100 (C100) (1960 – 68) were a British anti-nuclear protest group who campaigned for mass non-violent direct action (NVDA) in an effort to force the government to revise its defence policy. -

University of Warwick Institutional Repository: a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Phd at The

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/49428 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. THE UNIVERSITY OF WAJ@JCl( Library Declaration and Deposit Agreement 1. STUDENT DETAILS Please complete the following: Full name: Celia Hughes . University ID number: 0529464 . 2. THESIS DEPOSIT 2.1 I understand that under my registration at the University, I am required to deposit my thesis with the University in BOTH hard copy and in digital format. The digital version should normally be saved as a single pdf file. 2.2 The hard copy will be housed in the University Library. The digital version will be deposited in the University's Institutional Repository (WRAP). Unless otherwise indicated (see 2.3 below) this will be made openly accessible on the Internet and will be supplied to the British Library to be made available online via its Electronic Theses Online Service (EThOS) service. [At present, theses submitted for a [v'laster's degree by Research (MA, MSc, LLM, MS or MMedSci) are not being deposited in WRAP and not being made available via EthOS. This may change in future.] 2.3 In exceptional circumstances, the Chair of the Board of Graduate Studies may grant permission for an embargo to be placed on public access to the hard copy thesis for a limited period. -

The People in the Streets

herever there is a man who e*erc'ses authority, there is a man In this Issue: who resists authority.' LARGE-YES: SMALL-NO OSCAR WILDE WAY OUT OF THIS WORLD CORRESPONDENCE THE ANARCHIST W EEKLY-4d. 'J ’HE traditional climax—or rather, anti-climax—of the Aldermaston march is a' meaningless mass meet ing on Easter Monday somewhere The People in in central London. In 1959, I960, and 1961 this meeting was held in Trafalgar Square. But in 1961 members of the Committee of 100 staged an unofficial sit-down in . Grosvenor Square, and then a fascist . group booked Trafalgar Square for the Streets the following Easter Monday. So in 1962 the meeting was held in Hyde Park—and was followed by A rehearsal of what they COULD do an ominously silent picket in Gros venor Square and some running that the march was to be allowed to down, so they broughf in reinforce fights in other parts of the West go forward, but in Whitehall several ments and blocked Whitehall with End. more attempts were made to tear two coaches parked right across the In 1963 the meeting was held in down the banners and halt the road. But we kept , the initiative, Hyde Park again, but it might just march. Each time the police formed and after a few minutes and a few as well not have been held at all. a barrier it either broke through arrests we were pastj«the coaches Many members of the Committee weight of numbers or as in the case and through the cordons, and we of 100 had been calling for more of the coach barrier the marchers kept the road for the rest of White radical action for several weeks, and went around (and in some cases hall and for Pall Mali the CND leaders should have over) the obstacle and formed lines In Regent Street wegvvere getting known they would never get away right across the road to continue the thinned out a bit, but Be took over with it this time. -

SPAIN-Are WE Prepared? Relative “Freedom”—At Least So Far As the Foreign Press Was Concerned, “Old-Timers” Look for Their Support

ween the government which does tk' * . ^1e People who accept it In this Issue: ®re is a certain shameful solidarity.' VICTOR HUGO. Controversy on ‘the People in the S tre e ts’-p2 M A Y 4 1963 Vol 24 No 14 THE ANARCHIST WEEKLY-4d. 'J ’HE recent execution of the Spanish communist Julian Gri- mau in the teeth of world dis approval, and the tightening up of press censorship after a period of SPAIN-are WE prepared? relative “freedom”—at least so far as the foreign press was concerned, “old-timers” look for their support. France? (de Gaulle s brusque call Spanish “old-timers” ?). It is how actual presence at the various bases has given rise to speculations of a Of course they can count on the ing-off of- trade talks with Spain ever much more likely that the leased to them by Franco, could be change in the regime at top level. Army- leaders and the powerful following the execution of Grimau Spanish reactionaries are looking to of value to the reactionaries in the Last Sunday’s Observer prominently Sections of the Church, landowners does not promise Well, though on the United States for support if and event of American intervention in featured a report “by a Special Cor and industrialists, but is there any the other hand de Gaulle has shown when the explosion takes place in any struggle that might result from respondent” the gist of which is that reason to believe that in 1963 they willingness to mak? life difficult for Spain. As it is the regimes has a political coup-d’etat. -

Civil Defense and the Public Backlash Against Home Fallout Shelters, 1957-1963

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Summer 8-7-2012 "Little Holes to Hide In": Civil Defense and the Public Backlash Against Home Fallout Shelters, 1957-1963 John R. Whitehurst [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Whitehurst, John R., ""Little Holes to Hide In": Civil Defense and the Public Backlash Against Home Fallout Shelters, 1957-1963." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/58 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―LITTLE HOLES TO HIDE IN‖: CIVIL DEFENSE AND THE PUBLIC BACKLASH AGAINST HOME FALLOUT SHELTERS, 1957-1963 by JOHN WHITEHURST Under the Direction of John McMillian ABSTRACT Throughout the 1950s, U.S. policymakers actively encouraged Americans to participate in civil defense through a variety of policies. In 1958, amidst confusion concerning which of these policies were most efficient, President Eisenhower established the National Shelter Plan and a new civil defense agency titled The Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization. This agency urged homeowners to build private fallout shelters through print media. In response, Americans used newspapers, magazines, and science fiction novels to contest civil defense and the foreign and domestic policies that it was based upon, including nuclear strategy. Many Americans re- mained unconvinced of the viability of civil defense or feared its psychological impacts on socie- ty. -

Roles of Music in the Making of Social Movements: the Case of the British Nuclear Disarmament Movement, 1958–1963

UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE Minna Vähäsalo ”THEY’VE GOT THE BOMB, WE’VE GOT THE RECORDS!” Roles of Music in the Making of Social Movements: The Case of the British Nuclear Disarmament Movement, 1958–1963 _______________________________ Master’s thesis in History / MDP in Peace, Mediation and Conflict Research Tampere 2016 ABSTRACT University of Tampere School of Social Sciences and Humanities VÄHÄSALO MINNA: ”They’ve Got the Bomb, We’ve Got the Records!” Roles of Music in the Making of Social Movements: The Case of the British Nuclear Disarmament Movement, 1958–1963 Master’s thesis, 88 p., 3 appendix p. History October 2016 ________________________________________________________________________________ This thesis explores the roles music can play in the making of social movements. The theme is studied through the case of the British nuclear disarmament movement, 1958–1963. The focus is mainly on London and the national level, but the discussion is contrasted with examples from protests in the Glasgow region. By analysing participant perceptions on music, the study answers two main research questions. Firstly, how was music seen to influence the movement, and why? Secondly, how did contemporary musical and political phenomena shape the uses and perceptions of music in protest. The topic is discussed in the context of Cold War cultures in Britain in the late 1950s and early 1960s. This thesis provides an example of how local actors interpreted the Cold War, and responded to it using the cultural and social resources available for them. It also demonstrates how the Cold War influenced the political opportunities and internal dynamics of the movement. The British nuclear disarmament movement was a mostly non-aligned collection of groups, campaigns, individuals and protests which aimed at unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom.