Fill the Jails': Identity, Structure and Method in the Committee of 100, 1960 – 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 William Styles Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge September 2016 This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy William Styles British Domestic Security Policy and Communist Subversion: 1945-1964 This thesis is concerned with an analysis of British governmental attitudes and responses to communism in the United Kingdom during the early years of the Cold War, from the election of the Attlee government in July 1945 up until the election of the Wilson government in October 1964. Until recently the topic has been difficult to assess accurately, due to the scarcity of available original source material. However, as a result of multiple declassifications of both Cabinet Office and Security Service files over the past five years it is now possible to analyse the subject in greater depth and detail than had been previously feasible. The work is predominantly concerned with four key areas: firstly, why domestic communism continued to be viewed as a significant threat by successive governments – even despite both the ideology’s relatively limited popular support amongst the general public and Whitehall’s realisation that the Communist Party of Great Britain presented little by way of a direct challenge to British political stability. Secondly, how Whitehall’s understanding of the nature and severity of the threat posed by British communism developed between the late 1940s and early ‘60s, from a problem considered mainly of importance only to civil service security practices to one which directly impacted upon the conduct of educational policy and labour relations. -

Chapter 15: How Effective Are Peace Movements

Chapter 12: How Effective are Peace Movements? On 10 July 1997 Bob Overy made a presentation about the effectiveness - or otherwise - of peace movements. It was based on a booklet he had published in the early 1980s which members of the group read, or re-read, prior to the meeting. Present were: Christina Arber, John Brierley, Howard Clark, Annie Harrison, Yolanda Juarros Barcenilla, Bob Overy, Michael Randle, Carol Rank, Andrew Rigby. Presentation - Bob Overy Bob explained that he had written the original text with that title back in 1980-81 while he was doing his Ph.D at Peace Studies. It had subsequently been published as a booklet in 1982 by a Canadian publisher, who had, however, added ideas of his own to the Preface and Postscript - some of which Bob did not even agree with! - and somewhat revamped it with the second UN Special Session on Disarmament in mind. But Bob was mainly responsible for the middle bit. He was not planning to use the analysis he had made some 15 years ago to talk about the present. Instead he would summarise the main points, and it would be up to the group to consider whether or not it provided any useful ways of looking at today's movements and issues. The catalyst for the study was a review by A.J.P.Taylor, eminent historian and member of CND Executive, of a book by the war historian, Michael Howard. Taylor, concurring with the author's view, said that the attempt to abolish war was a vain and useless enterprise, but that he was proud to be associated with the peace movement when it was trying to stop particular wars. -

Close to Midnight CND General Secretary Kate Hudson Writes on How the US’ Nuclear Policy Is Taking Us Closer to War

caTHE MAGAZINmE OF THE CAMPAIGN pFOR NUCLEAR DaISARMAMENT igFEBRUARY 2018 n Close to midnight CND General Secretary Kate Hudson writes on how the US’ nuclear policy is taking us closer to war. AST MONTH the Bulletin of Atomic of Evil. It also revisited some of the ideas Scientists moved us half a minute closer of the early 1990s, calling for the Lto Midnight. At two minutes to, it’s development of bunker-busters and mini- the closest since the height of the Cold War. nukes for use in ‘regional conflicts’, The reasons cited are increasing nuclear understood at that time – in the aftermath risk, climate change and potentially harmful of the first Gulf War and the developing emerging technologies. But nuclear takes narrative around oil and resources – to centre stage: reckless language and provoca - mean the Middle East. tive action by both US and North Korea. The advent of President Obama To make matters worse, the latest US temporarily knocked the project on the nuclear posture review has just been head. His 2010 review ruled out the released. These reviews can be a powerful development of new nuclear weapons, indicator of a president’s intentions and this including bunker-busters. It also renounced one will, no doubt, be a taste of things to nuclear weapons use against non-nuclear come. The 2002 version included President states that the US considered compliant Bush’s demand for contingency plans for with the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. the use of nuclear weapons against at least At the time we hoped for more, after seven countries, including the so-called Axis Obama’s passionate Prague speech in 2009, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, CND 60th celebration at Aldermaston 162 Holloway Rd, London N7 8DQ 1st April, assemble at 12 020 7700 2393 noon. -

Andthe Anarchists Other Issues of "Anarchy"L Gontents of Il0

AilARCHYJ{0.109 3shillings lSpence 40cents "-*"*"'"'r ,Eh$ Russell andthe Anarchists Other issues of "Anarchy"l Gontents of il0. 109 Please note that the following issues are out of print: I to 15 inclusive, 26,27, 38, ANiARCHY 109 (Vol l0 No 3) MARCH 1970 65 March 1970 39, 66, 89, 90, 96, 98, 102. Vol. I 1961l. 1. Sex-and-Violence; 2. Workers' control; 3. What does anar- chism mcarr today?: 4. Deinstitutioni- sariorr; 5. Spain; 6. Cinema; 7. Adventure playgrourrd; 3. Anthropology; 9. Prison; 10. [ndustrial decentralisation. Neither God nor Master V. Ncill; 12. Who are the anarchists?; 13. Richard Drinnon 65 Direct action; 14. Disobcdience; 15. David Wills; 16. Ethics of anarchism; 17. Lum- lleilther God pcn proletariat ; I {l.Comprehensive schools; Russell and the anarchists 19. 'Ihcatrc; 20. Non-violence; 21. Secon- dary Vivian Harper 68 modern; 22. Marx and Bakunin. nor Master Vol. 3. l96f : 23. Squatters; 24. Com- murrity of scholars; 25. Cybernetics; 26. RIOHABD DNIililOI{ Counter-culture 'l'horcarri 27. Yor-rth; 28. Future of anar- chisml 2t). Spies for peace;30. Com- Kingsley lAidmer 18 rnurrity workshop; 31. Self-organising systcmsi 32. Orimc; 33. Alex Comfort; Kropotkin and his memoirs J4. Scicnce fiction. Nicolas Walter 84 .17. I won't votc; 38. Nottingham; 39. Tsoucn ITS Roors ARE DBEpLy BURIED, modern anarchism I Iorncr l-ancl 40. Unions; 41. Land; dates from the entry of the Bakuninists into the First Inter- 42. India; 43. Parents and teachers; 44, Observations on eNanttnv 104 l'rarrsport; 45. Thc Greeks;46. Anarchisrn national just a hundred years ago. -

Unit V 1. India As a Champion of World Peace and Justice A

UNIT V 1. INDIA AS A CHAMPION OF WORLD PEACE AND JUSTICE A peace movement is a social movement that seeks to achieve ideals such as the ending of a particular war (or all wars), minimize inter-human violence in a particular place or type of situation, and is often linked to the goal of achieving world peace. Means to achieve these ends include advocacy of pacifism, non-violent resistance, diplomacy, boycotts, peace camps, moral purchasing, supporting anti-war political candidates, legislation to remove the profit from government contracts to the Military–industrial complex, banning guns, creating open government and transparency tools, direct democracy, supporting Whistleblowers who expose War-Crimes or conspiracies to create wars, demonstrations, and national political lobbying groups to create legislation. The political cooperative is an example of an organization that seeks to merge all peace movement organizations and green organizations, which may have some diverse goals, but all of whom have the common goal of peace and humane sustainability. A concern of some peace activists is the challenge of attaining peace when those that oppose it often use violence as their means of communication and empowerment. Some people refer to the global loose affiliation of activists and political interests as having a shared purpose and this constituting a single movement, "the peace movement", an all encompassing "anti-war movement". Seen this way, the two are often indistinguishable and constitute a loose, responsive, event-driven collaboration between groups with motivations as diverse as humanism, environmentalism, veganism, anti- racism, feminism, decentralization, hospitality, ideology, theology, and faith. There are different ideas over what "peace" is (or should be), which results in a plurality of movements seeking diverse ideals of peace. -

Ernest Rodker (ER) Born May 1937 Interviewer: Felicity Winkley (FW) and Ruth Dewa (RD) Date: July 10Th 2015

After Hiroshima Interview transcript Interviewee: Ernest Rodker (ER) born May 1937 Interviewer: Felicity Winkley (FW) and Ruth Dewa (RD) Date: July 10th 2015 (0:00) ER: Uhh… I suppose compared to… I come from a family of of people who’d been involved in objection to, uh, particularly, war and… and battle. I mean, my father was German and not that I knew that much about him when I, when I was getting into the age when this was important to me but my, but I subsequently found that if these things had come through DNA then, then I’ve got a lot of it in my body ‘cause my, my dad is German and he was very involved in the anti-fascist movement in Germany. And um, although he didn’t talk much about it, I did get some stories from him but he was arrested and tortured and, and uh, uh, the person he was arrested with was beaten to death so he had a, a real experience of what being a protestor and being sort of against, um, the dominating force at the time in his country meant to him. He eventually got to this country and um, um, um, settled here. Uh, and my mother was very involved in the Communist Party and the Peace Movement, umm, in, in the years before I was born in, in the 40s. Oh sorry, um oh yes, yes after I was born but mostly in the 30s and 40s. My grandfather was a conscientious objector, um, into being called up in the First World War, which I knew nothing about really, so, um, I… was in the household d… didn’t really impress upon me the whole question of demonstrating, it was possibly a good move on my mother’s not to do that. -

Memories on a Monday: Peace Monday 11 May 2020

Memories on a Monday: Peace Monday 11 May 2020 Welcome to Memories on a Monday: Peace - sharing our heritage from Bruce Castle Museum & Archive. Following the commemorative events last week of VE Day, we turn now to looking at some of the ways we have marked peace in our communities in Haringey, alongside the strong heritage of the peace movement and activism in the borough. In July 2014, a memorial was unveiled alongside the woodland in Lordship Recreation Ground in Tottenham. Created by local sculptor Gary March, the sculpture shows two hands embracing a dove, the symbol of peace. Its design and installation followed a successful a campaign initiated by Ray Swain and the Friends of Lordship Rec to dedicate a permanent memorial to over 40 local people who tragically lost their lives in September 1940. They died following a direct hit by a high-explosive bomb falling on the Downhills public air raid shelter. It was the highest death toll in Tottenham during the Second World War. (You can see the sculpture and read more about this tragedy here and also here from the Summerhill Road website). Three years before, in Stroud Green, a Peace Garden was named and unveiled in 2011. It commemorates the 15 people who died, 35 people who were seriously injured, the destruction of 12 houses and the severe damage of Holy Trinity Church and 100 other homes in the area. The details below, can be read on the attached PDF. The Peace Garden Board can be found in the garden, at the junction where Stapleton Hall Road meets Granville Road, N4. -

Quaker Thought and Life Today

Quaker Thought and Life Today VOWMI 9 JULY 15, 1963 NUMBER 14 C!)f: puff and wheeze, we struggle and discuss. We have A Meeting's Creative Experience endless committee meetings. But j esus said where two or A Committee's Report three meet in my name I am there in the midst, and then they grow like the lily or the tree by the brook. I t isn't Letter from England effort, it isn't struggle that makes persons grow. It is life. by Colin Fawcett It is contact with the forces of life that does it. Growth is silent, gentle, quiet, unnoticed, but you can't have growth un Good Words for Love's Fools til you have the miracle of life and until it is in contact with by Sam Bradley the sources and the forces of life-soil, sun, water, and air. - R uFus M. JoNEs 1863 Bright-Churchill 1963 A Letter from the Past TWENTY· FIVE CENTS $5.00 A YEAR Under the Red and Black Star 306 FRIENDS JOURNAL July 15, 1963 FRIENDS JOURNAL UNDER THE RED AND BLACK STAR AMERICAN FRIENDS SERVICE COMMITTEE Lahsin Plants a Tree ORMALLY on Thursday afternoons Lahsin Hajar, N a 10-year-old Algerian boy, can be found in the carpentry workshop of the Quaker Center at Souk el Tleta, working on a bench he is making. Today, however, Published semimonthly, on the first and fifteenth of each month, at 1515 Cherry Street, Philadelphia 2, Penn he has been picked by the Quaker agriculturalist to sYlvania (LO 3-7669) by Friends Publishing Corporation. -

Indian-Nordic Encounters 1917-2006

Indian-Nordic Encounters 1917-2006 Tord Björk Folkrörelsestudiegruppen – Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam 1 Reclaim Gandhi – Indian-Nordic encounters 1917-2006 Content: Introduction……………………………………………………………………. 3. Part 1. Dialogue, Constructive Programme and Liberation Struggle 1917-1947 - Grundtvig meets Gandhi ………………………………………... 7. 1.2 Building an international solidarity movement for Indian liberation … .. 12. 1.3 Opposing Nazism and building an international work camp movement… 16. Part 2. Peace and Solidarity against any imperialism 1948-1969 – Anarchism, Theosophy and Mao meets Gandhi………………………….….. 22. 2.2 Four Gandhian and Indian influences changing Nordic countries………. 34. 2.3 Overcoming limitations of interpretation of Indian influences………….. 42. 2.4 Young theosophists and antiimperialists continious Gandhian struggle… 49. Part 3. Global Environmental Movement Period 1970-1989 – Ecology meets Gandhi……………………………………………………….. 51. 3.2 Challenging Western Environmentalism and UNCHE 1972……….……. 61. 3.3 Anti-nuclear Power and Alternative Movement…………………….…… 91. 3.4 Nordic peace, future studies and anti-imperialist initiatives……………. 102. 3.5 New struggles and influences from India 1983-1988…………...……… 108. Part 4. The Global Democracy Period 1989-2004 – Solidarity meets Gandhi…………………………………………………...... 113. 4.2 Gandhi Today in the Nordic countries………………………………..… 122. 4.3 Mumbai x 3………………………………………………………….….. 126. 4.4 Reclaim Gandhi…………………………………………………….…… 128. Appendix I Declaration of the Third World and the Human Environment……………… 132. Appendix II Manifesto -

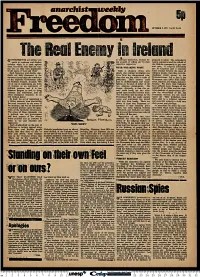

Standing on Their Own Feet Or on Ours?

anarchistmmweehly Vol 32 No 31 riOVERNMENTS are always very to extricate themselves, without be- prepared to admit. The campaign is quick to condemn and deplore ing accused of 'selling out' by their mainly centred around the refusal of ' violence when it is used against respective supporters. the Catholic community to pay rent them, but all the time they are wag- *2? and rates. If religious differences ing war on their own populations NEAR BREAKING POINT can be forgotten and a common in the name of 'Law and Order'. Such a situation shows \pry bond created between the mass of Such hypocrisy and double stan- clearly that nothing worthwhile can ordinary people, then this civil dis- dards are fully illustrated in the come from the compromised solu- obedience could spread to the statement issued after the conclusion tions that are the stock in trade of Protestant areas. Let us face it, the of the tripartite Government talks politicians. Their answers could Protestants also suffer from indig- on Northern Ireland. It reads: 'We lead to disillusionment and resent- nities, injustice, low wages, and poor are at one in condemning any form *SpV '■"■ t •■■■•.-•>a*-v.tv13fc:V-J~. ■ '. ¥r \£-\. ■':'<*.^^!.^/'Ui/^jKjp,-ki,f-^AJi^ fulness on the part of either of the . housing. We know that Catholics of violence as an instrument of il'*;(»»'>,i,^'lk"'f-l<*. -»fr''^ . Vt'/i'li'/-- 1 '' '*■ ■''■**4fflv- ■ ' V'^&f«Ufl*?tivr r two religious communities. The have suffered more because of the political pressure and it is our danger, obviously, is that this en- inability of the State and the capi- common purpose to seek to bring mity could break out into wide- talist methods of production to pro- violence and internment, and all spread open hostility between them. -

Aspects of Peace-Making

VOLUME XVI, NO. 24 JUNE 12, 1963 ASPECTS OF PEACE-MAKING THE question of whether the forms of "action" The leading editorial in the April 13 Freedom, developed by the peace movement are "effective" an anarchist weekly published in London, begins: is endlessly argued and no doubt should be. What What can be hoped for as a result of a is not always recognized is that this argument successful—as we assume it will be—sixth annual actually takes place against a background of "Aldermaston" march this Easter, can perhaps be considerable uncertainty concerning what assessed by drawing up a balance sheet of what has "effective" means, or ought to mean. In the terms been achieved by the previous five. of the politics of the past, an effective program is The Freedom writer, his eye fixed upon the one that leads to power. Today, however, it is by anarchist ideal of a free, voluntaristic human no means clear what pacifists would do with community, heads his article: "Aldermaston—a power, supposing they could obtain it. Pacifists Human Success Story but a Political Failure." He "in power" seems very much a contradiction in explains this judgment: terms, yet any action which is a protest against the It seems clear that the ruling classes of the world exercise of power by governmental authority may are not deterred (or disarmed) by good people be taken to imply that the protesters have in mind trampling 53 miles in their thousands, supported by a better way for that power to be used. possibly millions more who will be with them in spirit, even if the few days respite from life's routine The problem is so broad that a specific issue will be spent in other ways. -

Rethinking Gandhi and Nonviolent Relationality: Global Perspectives

Rethinking Gandhi and Nonviolent Relationality This book presents a rethinking of the world legacy of Mahatma Gandhi in this era of global violence. Through interdisciplinary research, key Gandhian concepts are revisited by tracing their genealogies in multiple histories of world contact and by foregrounding their relevance to contemporary struggles to regain the ‘humane’ in the midst of global conflict. The relevance of Gandhian notions of ahimsa and satyagraha is assessed in the context of contemporary events, when religious fundamentalisms of various kinds are competing with the arrogance and unilateralism of imperial capital to reduce the world to a state of international lawlessness. Covering a wide and comprehensive range of topics such as Gandhi’s vegetarianism and medical practice, the book analyzes his successes and failures as a liti- gator in South Africa, his experiments with communal living and his con- cepts of non-violence and satyagraha. The book combines historical, philosophical and textual readings of dif- ferent aspects of the leader’s life and works. It will be of interest to students and academics interested in peace and conflict studies, South Asian history, world history, postcolonial studies and studies on Gandhi. Debjani Ganguly is Head of the Humanities Research Centre in the Research School of Humanities at the Australian National University. Author of Caste, Colonialism and Countermodernity: Notes on a Postcolonial Herme- neutics of Caste (also published by Routledge), she also co-edited Edward Said: The Legacy