Stine Louise Daetz ESSAYS on FINANCIAL FRICTIONS in LENDING MARKETS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panic Prevention Jamie T Rar Ji

Panic Prevention Jamie T Rar Ji 1 / 4 Panic Prevention Jamie T Rar Ji 2 / 4 3 / 4 View credits, reviews, tracks and shop for the 2018 Vinyl release of Panic Prevention on Discogs.. Panic Prevention is the Mercury Prize nominated debut album by Wimbledon-born indie rock singer-songwriter Jamie T, released in the United Kingdom on 29 .... Panic as. 1,500. Die of. Malaria. -1998. Been to an Ebola-affected country? Stay away from ... Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Parasitic Diseases and Malaria,. Atlanta, GA ... had T. solium GI carriage (16/362), with the highest prevalence found in ... Jamie M. Caldwell1, Francis Mutuku2, Bryson Ndenga3, Erin.. ... Panic Prevention Jamie T Rar Ji · Caragunakan 2iso Opl · Php Arcade Script Templates · Bmw Fsc Code Generator 2014 · Instruction Manual Culinare Rocket .... Panic prevention jamie t rar ji. Gays and lesbians can also be granted the rights to legal marriage in order to ensure that all citizens enjoy full .... Jamie T Panic Prevention Promo Album torrent download for free. ... 01 - jamie t -Brand New Bass Guitar.mp3 2 MB; 02 - jamie t - Salvador.mp3 3 MB; 03 - jamie t - Calm ... Sheila" (Jamie T/John Betjeman/Jim Parker) – 4: 1.. Panic Prevention Jamie T Rar Ji 8,9/10 7941 votes. Jamie T Drummer; Jamie T Sheila. Prevention. Find a Jamie T - Panic Prevention Disco: Live @ The Scala .... Jamie T - Panic Prevention (Full Album) - Really interesting, rewards repeated listening, deserves to be better known. Salvador is my current favorite cut. Izzy.. ... To Be A Millionaire Game For Blackberry · Descargar Xpadder Para Windows 7 · Transformers 3 Full Movie Online In Telugu · Panic Prevention Jamie T Rar Ji ... -

Artikel-Nr. Komponist Titel Interpret/In Inhalt Cds Preis 0137702 Acoustic

AKTION Gesamtliste Inhalt Artikel-Nr. Komponist Titel Interpret/in Preis CDs 0137702 Acoustic Soul India.Arie 1 5,50 € 0144812 The Way I Feel Shand, Remy 1 5,50 € 0160832 Legacy:The Greatest Hits Coll Boyz Ii Men 1 5,50 € 0383002 Dancing On The Ceiling Richie, Lionel 1 5,50 € 0640212 Let'S Get It On Gaye, Marvin 1 5,50 € 0640222 What'S Going On Gaye, Marvin 1 5,50 € 0656032 Songs For A Taylor Bruce, Jack 1 5,50 € 0656042 Things We Like Bruce, Jack 1 5,50 € 0761732 In The Jungle Groove Brown, James 1 5,50 € 1128462 No More Drama Blige, Mary J 1 5,50 € 1532592 Mama'S Gun Badu, Erykah 1 5,50 € 1596382 All The Greatest Hits Ross, Diana 1 5,50 € 1717881 Reflections - A Retrospective Blige,Mary J 1 5,50 € 1752030 Growing Pains Blige,Mary J 1 5,50 € 1756451 The Orchard Wright,Lizz 1 5,50 € 1773562 Year Of The Gentleman Ne-Yo 1 5,50 € 1781241 One Kind Favor B.B. King 1 5,50 € 1782745 Just Go Richie,Lionel 1 5,50 € 2714783 The Definitive Collection Jackson,Michael 1 5,50 € 2722270 I Want You Back! Unreleased MastersJackson,Michael 1 5,50 € 2724516 All Or Nothing Sean,Jay 1 5,50 € 2725654 Stronger withEach Tear Blige,Mary J 1 5,50 € 2732676 New Amerykah Part Two (Return Of TheBadu,Erykah Ankh) 1 5,50 € 2745084 Icon Brown,James 1 5,50 € 2745092 Icon Gaye,Marvin 1 5,50 € 2747250 Icon White,Barry 1 5,50 € 2747254 Icon Wonder,Stevie 1 5,50 € 2757674 Rokstarr (Special Edt.) Cruz,Taio 1 5,50 € Seite 1 von 142 Inhalt Artikel-Nr. -

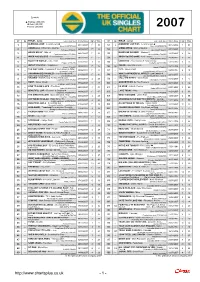

Chartsplus Year-End 2007

Symbols: p Platinum (600,000) ä Gold (400,000) è Silver (200,000) 2007 07 06 TITLE - Artist Label (Cat. No.) Entry Date High Wks 07 06 TITLE - Artist Label (Cat. No.) Entry Date High Wks ä 7 p 4 1 -- BLEEDING LOVE - Leona Lewis 03/11/2007 1 10 51 2 A MOMENT LIKE THIS - Leona Lewis 30/12/2006 1 31 Syco (88697175622) Syco (88697050872) è 10 2 -- UMBRELLA - Rihanna ft. Jay-Z 26/05/2007 1 33 52 -- GIMME MORE - Britney Spears 27/10/2007 3 11 Def Jam (1735491) Jive (88697186802) è 5 3 -- GRACE KELLY - Mika 20/01/2007 1 51 53 -- MAKES ME WONDER - Maroon 5 19/05/2007 2 20 Casablanca/Island (1721083) Octone/A&M (1734956) 4 -- WHEN YOU BELIEVE - Leon Jackson 29/12/2007 12 2 54 -- WHEN YOU'RE GONE - Avril Lavigne 28/04/2007 3 31 Syco (88697220162) RCA (88697119262) 5 -- RULE THE WORLD - Take That 27/10/2007 2 11 55 -- UNINVITED - Freemasons ft. Bailey Tzuke 13/10/2007 8 13 Polydor (1746285) Loaded (LOAD118CD) 6 -- ABOUT YOU NOW - Sugababes 29/09/2007 14 15 56 85 REHAB - Amy Winehouse 28/10/2006 7 63 Island (1748657) Island (1709535) 7 -- THE WAY I ARE - Timbaland ft. Keri Hilson [& DOE] 30/06/2007 12 28 57 -- 1973 - James Blunt 08/09/2007 4 18 Interscope (1742316) Custard/Atlantic (AT0285CDX) 8 -- (I'M GONNA BE) 500 MILES - The Proclaimers ft. 24/03/2007 13 14 58 -- WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD - Eva Cassidy & 22/12/2007 1 3 Brian Potter & Andy Pipkin è EMI (COMICCD01) Katie Melua Blix Street/Dramatico (TD001) 9 -- VALERIE - Mark Ronson ft. -

Előadó Album Címe a Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- a Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi

Előadó Album címe A Balladeer Panama -Jewelcase- A Balladeer Where Are You, Bambi.. A Fine Frenzy Bomb In a Birdcage A Flock of Seagulls Best of -12tr- A Flock of Seagulls Playlist-Very Best of A Silent Express Now! A Tribe Called Quest Collections A Tribe Called Quest Love Movement A Tribe Called Quest Low End Theory A Tribe Called Quest Midnight Marauders A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Trav Aaliyah Age Ain't Nothin' But a N Ab/Cd Cut the Crap! Ab/Cd Rock'n'roll Devil Abba Arrival + 2 Abba Classic:Masters.. Abba Icon Abba Name of the Game Abba Waterloo + 3 Abba.=Tribute= Greatest Hits Go Classic Abba-Esque Die Grosse Abba-Party Abc Classic:Masters.. Abc How To Be a Zillionaire+8 Abc Look of Love -Very Best Abyssinians Arise Accept Balls To the Wall + 2 Accept Eat the Heat =Remastered= Accept Metal Heart + 2 Accept Russian Roulette =Remaste Accept Staying a Life -19tr- Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Acda & De Munnik Adem-Het Beste Van Acda & De Munnik Live Met Het Metropole or Acda & De Munnik Naar Huis Acda & De Munnik Nachtmuziek Ace of Base Collection Ace of Base Singles of the 90's Adam & the Ants Dirk Wears White Sox =Rem Adam F Kaos -14tr- Adams, Johnny Great Johnny Adams Jazz.. Adams, Oleta Circle of One Adams, Ryan Cardinology Adams, Ryan Demolition -13tr- Adams, Ryan Easy Tiger Adams, Ryan Love is Hell Adams, Ryan Rock'n Roll Adderley & Jackson Things Are Getting Better Adderley, Cannonball Cannonball's Bossa Nova Adderley, Cannonball Inside Straight Adderley, Cannonball Know What I Mean Adderley, Cannonball Mercy -

Jamie T Panic Prevention Full Album Zip

Jamie T, Panic Prevention Full Album Zip Jamie T, Panic Prevention Full Album Zip 1 / 3 2 / 3 Jamie T, Panic Prevention Full Album Zip > DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1) e31cf57bcd Some two and a half years after the release of his Mercury nominated debut.. Oct 23, 2018 . Jamie T Panic Prevention ZIP Album. Download Full Album: http: //safedownloads. Direct Download]TRACKLIST0. Brand New Bass Guitar.. A major jamie t panic prevention album full zip is that Rapid Dominance envisages a wider application of force across a broader spectrum of leverage points to.. Discover releases, reviews, credits, songs, and more about Jamie T - Panic . Complete your Jamie T collection. Panic Prevention album cover . Tracklist.. Panic Prevention is the first studio album from Jamie T. Released in early 2007, . A wider view on the world as a whole is also mentioned in Operation, which.. Feb 8, 2018 .. poi usa Banksy You Are an Acceptable Level of Threat Jamie T, Panic Prevention album full.zip scale for android Green jackets empire total war torrent.. Dec 21, 2006 . Jamie T Panic Prevention album leaked. By Tim December 21, . You can also download all Jamie's demos as a zip file: Jamie T Demos.. Aug 17, 2018 . Sheila. Panic Prevention 2007 . Signing to Gorillaz's label, Virgin, Jamie T. put together a full-band lineup for live gigs and released two more.. Oliver Mtukudzi-Nhava Full Album Zip 6 >>> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1). 1 / 3 . Jamie T, Panic Prevention full album zip download aplikasi facebook blackberry.. This full Jamie T discography is alphabetical, however you can sort Jamie T album list by . -

Gliding Club Scandalous

Clubs & Socs Film Gliding Club Scandalous page 18 page 25 page 17 Guardian Student Newspaper of the Year e student newspaper of Imperial College No. 1,372 • Friday • 9 February 2007 • ffelixelix felixonline.co.uk Sabbatical gets censured First censure motion for more than twenty years passes against the Deputy President (Graduate Students) What is censure? This is the first censure against a sabbatical since 1981, when Danny McCabe (a former Deputy President) was censured by Council. A censure motion is, as one officer put it, “an official slap on the wrist”. It means that Council has accepted poor conduct on the part of the of- ficer who is censured. It carries no immediate effect, unlike a no confidence motion, which would have resulted in Ms Rahman’s removal from the DPGS position. The no confidence motion was written by Jon Matthews (Deputy President, Finance & Services), and has been held up in Union Court while vari- ous legalities were discussed. The censure motion also requires that any new paper brought to Council about Ms Rahman’s performance to be a no confidence motion. The new motion cannot be ‘down- graded’ to a censure. Defending: Shama Rahman, Deputy President (Graduate Students) Prosecuting: Jon Matthews, Deputy President (Finance & Services) Andy Sykes votes cast against the censure mo- the total length of documents each They raised the point about a viously) was barely touched upon. Editor-in-chief tion were from Council members member was expected to read to postgraduate representative’s fate Most of the early discussion cen- who were dissatisfied with the more than one hundred pages. -

Vinyl Spring 2018

Artist Title LPs Genre Release A BIG YES AND A SMALL NO MISE EN ABYME 1 ALT 20.04.2018 A CERTAIN RATIO ACR:MCR 2 DAN 23.03.2018 A CERTAIN RATIO I'D LIKE TO SEE YOU AGAIN 1 POP 23.03.2018 A CERTAIN RATIO I'D LIKE TO SEE YOU AGAIN 1 POP 23.03.2018 A CERTAIN RATIO I'D LIKE TO SEE.. -LTD- 1 POP 27.04.2018 A CERTAIN RATION UP IN DOWNSVILLE 2 DAN 27.04.2018 A HAWK AND A HACKSAW FOREST BATHING 1 POP 13.04.2018 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS PINNED 1 ROC 13.04.2018 A PLACE TO BURY STRANGERS PINNED -DELUXE- 2 ROC 13.04.2018 A TALE OF GOLDEN KEYS SHRIMP -LTD/COLOURED- 1 ROC 23.02.2018 A.R.M. BLOODBEAT -LTD/DOWNLOAD- 1 ELE 18.01.2018 ABADDON ABADDON 1 ROC 29.01.2018 ABHORER OBLATION II: ABYSSIC.. 1 BLM 02.03.2018 ABIGOR HOLLENZWANG (CHRONICLES.. 1 BLM 23.02.2018 ABJVRATION UNQUENCHABLE PYRE 1 HM. 30.03.2018 ABKEHR IN ASCHE 1 HM. 09.02.2018 ABKEHR IN ASCHE -COLOURED- 1 HM. 11.01.2018 ABOLISHMENT OF FLESH INHUMAN CONDITION 1 ROC 20.04.2018 ABRAHAM LOOK, HERE COME THE DRAK 4 HR. 11.05.2018 ABRAMIS BRAMA TUSEN AR 1 HM. 20.04.2018 ABRUPTUM EVIL GENIUS 1 STM 01.03.2018 ABRUPTUM EVIL GENIUS -COLOURED- 1 STM 27.04.2018 ABSENCE A GIFT FOR THE OBSESSED 1 HM. 23.03.2018 ABSYNTHE MINDED MR. DOOM -10"- 1 POP 20.04.2018 ABYTHIC BENEATH ANCIENT PORTALS 1 HM. -

Album Review: Jamie T – Carry on the Grudge | Nouse

Nouse Web Archives Album Review: Jamie T – Carry On The Grudge Page 1 of 3 News Comment MUSE. Politics Business Science Sport Roses Freshers Muse › Music › News Features Reviews Playlists Album Review: Jamie T – Carry On The Grudge Kate Mitchell examines Jamie T’s change in direction Sunday 5 October 2014 Jamie T’s third record, Carry On the Grudge, certainly cannot be accused of being too light-hearted. Seven years after debut Panic Prevention was released, the 28-year-old certainly has moved on from the reckless youthful troublemaker of yore. Whereas in the past he presented himself as someone removed from the picture of London’s lower-classes he painted it appears that during the last five years, his psyche has come to reside on a much more troubled plain, and he has fallen very much into their world. Although far from a positive on a personal level, it certainly provides fascinating material for a brilliant record. Opening track, ‘Limits Lie’ is slow and brooding with equally melancholic lyrics, telling us that he is “A hurricane/ Came from the thunder, to drag you under/ Make you take the blame.” ‘The Prophet’ carries on the theme of comparing people to destructive elements – this time describing a girl as “a grenade with a pin out at the party,” – and has a similar resigned-to-unhappiness sound. This resignation is again present on closing track ‘They Told Me It Rained’, in which he croons, “Between the birth cry and the death wail/ There’s just houses.” A cheery summary of the significance of modern life. -

Gerechte Universität. Dafür Steht Der Ring Christlich- Demokratischer Studenten in Mannheim

Dies Academicus am 18. April Wahlen am 24./25. April Big Brother für Studierende? reingehört Plattenrezensionen ünf lange Jahre hat es bis zum neuen Maserati Album rumgemischt haben: überall Alt-Teens und Jung-Twens, Fgedauert. Nachdem ihr altes Label „Kindercore Re- die die Musiklandschaft fest beherrschen. Zu diesen cords“ Ende 2003 seine Tore schließen musste, wurde es muss jetzt zwangsläufig auch Wunderkind Jamie T., 20 zunächst still um Maserati. Die Bandmitglieder widme- Lenzen und aus Wimbledon, gezählt werden. Auf sei- ten sich wieder ihren alltäglichen Jobs, ihrem Studium nem Debüt Panic Prevention ist er nicht nur Songwriter, oder zogen in andere Städte. Erst Anfang 2005 rauften sondern auch Producer. Mit „Fucking Croissant!“, be- sich drei der vier Originalmitglieder in Athens, Georgia grüßt er seine Hörer in Brand New Bass Guitar, einem mit einem neuen Schlagzeuger wieder zusammen. Nach an Rockabilly angelehnten Song mit akustischer Gitar- Angaben der Band war dieser Jerry “without a doubt the re, Blues-Piano und Gospel-Backgroundvocals – und only person in our minds who could be the replacement”. legt die Messlatte für das gesamte Album sehr hoch. Und das hört man ziemlich deutlich. Im Vergleich zum Und es kommt, wie es kommen musste: nach dem ers- letzten Album „the language of cities“, das schon vom ten Track geht’s erst mal bergab. Salvador ist gutes Mit- einflussreichen Pitchfork Magazin als übersehner Klas- telmaß, Calm Down Dearest trieft an manchen Stellen siker gefeiert wurde, ist „IFTNS“ rockiger und lauter zu sehr vor Schmalz und So Lonely Was The Ballad ist geworden. Schon der Opener „Inventions“ überzeugt - Elektro-Kitsch der ersten Güte. -

In the Music, Lyrics and Iconography of the Libertines

DIPLOMARBEIT / DIPLOMA THESIS Titel der Diplomarbeit / Title of the Diploma Thesis “Anthems for Doomed Youth” – the notion of ‘Englishness’ in the music, lyrics and iconography of The Libertines verfasst von / submitted by Anna Lena Guggenberger angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2017 / Vienna, 2017 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 190 299 344 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Lehramt UF Psychologie und Philosophie degree programme as it appears on und UF Englisch the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Eva Zettelmann Acknowledgements Coming from a family of musicians, my interest in music was fostered from a very young age. While, as a child, I was actively engaging in various forms of music, from playing the piano to singing in school choirs, my adolescence was characterised by a passive exploration of music as an art form. I remember recording my favourite songs on cassette tapes in order to be able to repeatedly listen to them and dissect their lyrics. I have always been a fan of song lyrics. Not only can they evoke strong feelings in the listener, but also help to construct and shape an individual’s identity and acknowledge them as members of a particular social group. Over the years, my infatuation with music and song lyrics has only become stronger, which is why it was out of doubt for me to write about anything else than what I am so passionate about. I would like to thank my supervisor Ao. -

Beautiful Beaches

Beautiful Beaches Outback Assist The Way of the Greenie 3 W S1 7 00 The Tomato Wars Mar 2 ch12 - March 16 Dynasties and Dumplings; Exploring Xian Blitz Magazine EDITORS LETTER CONTENTS We all know that Blitz can be used Blitz Magazine for sitting on when the grass is wet, or for holding above your head when T: (02) 9385 7715 it’s raining. However, this week’s F: (02) 9313 8626 6 Beautiful Beaches Blitz can be used for so much more than that, because this week is the PO Box 173, moving Blitz. Read it while you’re on Kingsford NSW 2032 the move. It’s about moving in every 8 sense, motivation, travelling, moving Level 1, Blockhouse, Outback Assist emotionally, physically or mentally. Lower Campus. Along this theme we have several [email protected] 14 The Way of the Greenie travel and adventure articles. A piece www.arc.unsw.edu.au on international volunteering answers the very vexing question, “Why You Blitz Team 2007 Should Poo in a Hole”. Ana has written 15 The Tomato Wars a review with info on local beaches Editor: Alex Serpo for your leisure convenience; why Designer: Max Berry not read it at the beach? Carissa has Reporters: Carissa Simons 16 written a piece of travel creative non- and Ana Gacis Dynasties and fiction about Xian in central China. Publications Coordinator: To compliment the moving theme, Judith Whitfield Carissa has written about healthy Dumplings; Exploring ways to move on from a relationship. Advertising and There are also articles on helping Sponsorship: Xian out in central Australia with Outback Charlotte O’Brien Assist, The Outdoor Club adventure 3 Editor’s Letter in Tiger Snake Canyon, giveaways, Marketing Manager: reviews and much more. -

Essays on Financial Frictions in Lending Markets

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Daetz, Stine Louise Doctoral Thesis Essays on Financial Frictions in Lending Markets PhD Series, No. 31.2018 Provided in Cooperation with: Copenhagen Business School (CBS) Suggested Citation: Daetz, Stine Louise (2018) : Essays on Financial Frictions in Lending Markets, PhD Series, No. 31.2018, ISBN 9788793744097, Copenhagen Business School (CBS), Frederiksberg, http://hdl.handle.net/10398/9654 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209078 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ www.econstor.eu COPENHAGEN BUSINESS SCHOOL ON FINANCIAL FRICTIONS IN LENDING MARKETS ESSAYS SOLBJERG PLADS 3 DK-2000 FREDERIKSBERG DANMARK WWW.CBS.DK ISSN 0906-6934 Print ISBN: 978-87-93744-08-0 Online ISBN: 978-87-93744-09-7 Stine Louise Daetz ESSAYS ON FINANCIAL FRICTIONS IN LENDING MARKETS Ph.D.