A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-11/780

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

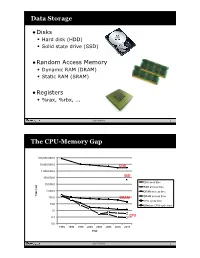

Data Storage the CPU-Memory

Data Storage •Disks • Hard disk (HDD) • Solid state drive (SSD) •Random Access Memory • Dynamic RAM (DRAM) • Static RAM (SRAM) •Registers • %rax, %rbx, ... Sean Barker 1 The CPU-Memory Gap 100,000,000.0 10,000,000.0 Disk 1,000,000.0 100,000.0 SSD Disk seek time 10,000.0 SSD access time 1,000.0 DRAM access time Time (ns) Time 100.0 DRAM SRAM access time CPU cycle time 10.0 Effective CPU cycle time 1.0 0.1 CPU 0.0 1985 1990 1995 2000 2003 2005 2010 2015 Year Sean Barker 2 Caching Smaller, faster, more expensive Cache 8 4 9 10 14 3 memory caches a subset of the blocks Data is copied in block-sized 10 4 transfer units Larger, slower, cheaper memory Memory 0 1 2 3 viewed as par@@oned into “blocks” 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 3 Cache Hit Request: 14 Cache 8 9 14 3 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 4 Cache Miss Request: 12 Cache 8 12 9 14 3 12 Request: 12 Memory 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sean Barker 5 Locality ¢ Temporal locality: ¢ Spa0al locality: Sean Barker 6 Locality Example (1) sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < n; i++) sum += a[i]; return sum; Sean Barker 7 Locality Example (2) int sum_array_rows(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (i = 0; i < M; i++) for (j = 0; j < N; j++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 8 Locality Example (3) int sum_array_cols(int a[M][N]) { int i, j, sum = 0; for (j = 0; j < N; j++) for (i = 0; i < M; i++) sum += a[i][j]; return sum; } Sean Barker 9 The Memory Hierarchy The Memory Hierarchy Smaller On 1 cycle to access CPU Chip Registers Faster Storage Costlier instrs can L1, L2 per byte directly Cache(s) ~10’s of cycles to access access (SRAM) Main memory ~100 cycles to access (DRAM) Larger Slower Flash SSD / Local network ~100 M cycles to access Cheaper Local secondary storage (disk) per byte slower Remote secondary storage than local (tapes, Web servers / Internet) disk to access Sean Barker 10. -

45-Year CPU Evolution: One Law and Two Equations

45-year CPU evolution: one law and two equations Daniel Etiemble LRI-CNRS University Paris Sud Orsay, France [email protected] Abstract— Moore’s law and two equations allow to explain the a) IC is the instruction count. main trends of CPU evolution since MOS technologies have been b) CPI is the clock cycles per instruction and IPC = 1/CPI is the used to implement microprocessors. Instruction count per clock cycle. c) Tc is the clock cycle time and F=1/Tc is the clock frequency. Keywords—Moore’s law, execution time, CM0S power dissipation. The Power dissipation of CMOS circuits is the second I. INTRODUCTION equation (2). CMOS power dissipation is decomposed into static and dynamic powers. For dynamic power, Vdd is the power A new era started when MOS technologies were used to supply, F is the clock frequency, ΣCi is the sum of gate and build microprocessors. After pMOS (Intel 4004 in 1971) and interconnection capacitances and α is the average percentage of nMOS (Intel 8080 in 1974), CMOS became quickly the leading switching capacitances: α is the activity factor of the overall technology, used by Intel since 1985 with 80386 CPU. circuit MOS technologies obey an empirical law, stated in 1965 and 2 Pd = Pdstatic + α x ΣCi x Vdd x F (2) known as Moore’s law: the number of transistors integrated on a chip doubles every N months. Fig. 1 presents the evolution for II. CONSEQUENCES OF MOORE LAW DRAM memories, processors (MPU) and three types of read- only memories [1]. The growth rate decreases with years, from A. -

Cuda C Best Practices Guide

CUDA C BEST PRACTICES GUIDE DG-05603-001_v9.0 | June 2018 Design Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................ vii What Is This Document?..................................................................................... vii Who Should Read This Guide?...............................................................................vii Assess, Parallelize, Optimize, Deploy.....................................................................viii Assess........................................................................................................ viii Parallelize.................................................................................................... ix Optimize...................................................................................................... ix Deploy.........................................................................................................ix Recommendations and Best Practices.......................................................................x Chapter 1. Assessing Your Application.......................................................................1 Chapter 2. Heterogeneous Computing.......................................................................2 2.1. Differences between Host and Device................................................................ 2 2.2. What Runs on a CUDA-Enabled Device?...............................................................3 Chapter 3. Application Profiling............................................................................. -

Mi!!Lxlosalamos SCIENTIFIC LABORATORY

LA=8902-MS C3b ClC-l 4 REPORT COLLECTION REPRODUCTION COPY VAXNMS Benchmarking 1-’ > .— u) 9 g .— mi!!lxLOS ALAMOS SCIENTIFIC LABORATORY Post Office Box 1663 Los Alamos. New Mexico 87545 — wAifiimative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer b . l)lS(”L,\l\ll K “Thisreport wm prcpmd J, an xcttunt ,,1”wurk ,pmwrd by an dgmcy d the tlnitwl SIdtcs (kvcm. mm:. Ncit her t hc llniml SIJIL.. ( Lwcrnmcm nor any .gcncy tlhmd. nor my 08”Ihcif cmployccs. makci my wur,nly. mprcss w mphd. or JwImL.s m> lcg.d Iululity ur rcspmuhdily ltw Ilw w.cur- acy. .vmplctcncs. w uscftthtc>. ttt”any ml’ormdt ml. dpprdl us. prudu.i. w proccw didowd. or rep. resent%Ihd IIS us wuukl not mfrm$e priwtcly mvnd rqdtts. Itcl”crmcti herein 10 my sp.xi!l tom. mrcial ptotlucr. prtxcm. or S.rvskc hy tdc mmw. Irdcnmrl.. nmu(a.lurm. or dwrwi~.. does nut mmwsuily mnstitutc or reply its mdursmwnt. rccummcnddton. or favorin: by the llniwd States (“mvcmment ormy qxncy thctcd. rhc V!C$VSmd opinmm d .mthor% qmxd herein do nut net’. UMrily r;~lt or died lhow. ol”the llnttcd SIJIL.S( ;ovwnnwnt or my ugcncy lhure of. UNITED STATES .. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY CONTRACT W-7405 -ENG. 36 . ... LA-8902-MS UC-32 Issued: July 1981 G- . VAX/VMS Benchmarking Larry Creel —. I . .._- -- ----- ,. .- .-. .: .- ,.. .. ., ..,..: , .. .., . ... ..... - .-, ..:. .. *._–: - . VAX/VMS BENCHMARKING by Larry Creel ABSTRACT Primary emphasis in this report is on the perform- ance of three Digital Equipment Corporation VAX-11/780 computers at the Los Alamos National Laboratory. Programs used in the study are part of the Laboratory’s set of benchmark programs. -

Cache-Aware Roofline Model: Upgrading the Loft

1 Cache-aware Roofline model: Upgrading the loft Aleksandar Ilic, Frederico Pratas, and Leonel Sousa INESC-ID/IST, Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal ilic,fcpp,las @inesc-id.pt f g Abstract—The Roofline model graphically represents the attainable upper bound performance of a computer architecture. This paper analyzes the original Roofline model and proposes a novel approach to provide a more insightful performance modeling of modern architectures by introducing cache-awareness, thus significantly improving the guidelines for application optimization. The proposed model was experimentally verified for different architectures by taking advantage of built-in hardware counters with a curve fitness above 90%. Index Terms—Multicore computer architectures, Performance modeling, Application optimization F 1 INTRODUCTION in Tab. 1. The horizontal part of the Roofline model cor- Driven by the increasing complexity of modern applica- responds to the compute bound region where the Fp can tions, microprocessors provide a huge diversity of compu- be achieved. The slanted part of the model represents the tational characteristics and capabilities. While this diversity memory bound region where the performance is limited is important to fulfill the existing computational needs, it by BD. The ridge point, where the two lines meet, marks imposes challenges to fully exploit architectures’ potential. the minimum I required to achieve Fp. In general, the A model that provides insights into the system performance original Roofline modeling concept [10] ties the Fp and the capabilities is a valuable tool to assist in the development theoretical bandwidth of a single memory level, with the I and optimization of applications and future architectures. -

ARM-Architecture Simulator Archulator

Embedded ECE Lab Arm Architecture Simulator University of Arizona ARM-Architecture Simulator Archulator Contents Purpose ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Description ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Block Diagram ............................................................................................................................ 2 Component Description .............................................................................................................. 3 Buses ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 µP .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Caches ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Memory ................................................................................................................................................. 3 CoProcessor .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Using the Archulator ...................................................................................................................... -

Multi-Cycle Datapathoperation

Book's Definition of Performance • For some program running on machine X, PerformanceX = 1 / Execution timeX • "X is n times faster than Y" PerformanceX / PerformanceY = n • Problem: – machine A runs a program in 20 seconds – machine B runs the same program in 25 seconds 1 Example • Our favorite program runs in 10 seconds on computer A, which hasa 400 Mhz. clock. We are trying to help a computer designer build a new machine B, that will run this program in 6 seconds. The designer can use new (or perhaps more expensive) technology to substantially increase the clock rate, but has informed us that this increase will affect the rest of the CPU design, causing machine B to require 1.2 times as many clockcycles as machine A for the same program. What clock rate should we tellthe designer to target?" • Don't Panic, can easily work this out from basic principles 2 Now that we understand cycles • A given program will require – some number of instructions (machine instructions) – some number of cycles – some number of seconds • We have a vocabulary that relates these quantities: – cycle time (seconds per cycle) – clock rate (cycles per second) – CPI (cycles per instruction) a floating point intensive application might have a higher CPI – MIPS (millions of instructions per second) this would be higher for a program using simple instructions 3 Performance • Performance is determined by execution time • Do any of the other variables equal performance? – # of cycles to execute program? – # of instructions in program? – # of cycles per second? – average # of cycles per instruction? – average # of instructions per second? • Common pitfall: thinking one of the variables is indicative of performance when it really isn’t. -

Multi-Tier Caching Technology™

Multi-Tier Caching Technology™ Technology Paper Authored by: How Layering an Application’s Cache Improves Performance Modern data storage needs go far beyond just computing. From creative professional environments to desktop systems, Seagate provides solutions for almost any application that requires large volumes of storage. As a leader in NAND, hybrid, SMR and conventional magnetic recording technologies, Seagate® applies different levels of caching and media optimization to benefit performance and capacity. Multi-Tier Caching (MTC) Technology brings the highest performance and areal density to a multitude of applications. Each Seagate product is uniquely tailored to meet the performance requirements of a specific use case with the right memory, NAND, and media type and size. This paper explains how MTC Technology works to optimize hard drive performance. MTC Technology: Key Advantages Capacity requirements can vary greatly from business to business. While the fastest performance can be achieved using Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) cache, the data in the DRAM is not persistent through power cycles and DRAM is very expensive compared to other media. NAND flash data survives through power cycles but it is still very expensive compared to a magnetic storage medium. Magnetic storage media cache offers good performance at a very low cost. On the downside, media cache takes away overall disk drive capacity from PMR or SMR main store media. MTC Technology solves this dilemma by using these diverse media components in combination to offer different levels of performance and capacity at varying price points. By carefully tuning firmware with appropriate cache types and sizes, the end user can experience excellent overall system performance. -

CS2504: Computer Organization

CS2504, Spring'2007 ©Dimitris Nikolopoulos CS2504: Computer Organization Lecture 4: Evaluating Performance Instructor: Dimitris Nikolopoulos Guest Lecturer: Matthew Curtis-Maury CS2504, Spring'2007 ©Dimitris Nikolopoulos Understanding Performance Why do we study performance? Evaluate during design Evaluate before purchasing Key to understanding underlying organizational motivation How can we (meaningfully) compare two machines? Performance, Cost, Value, etc Main issue: Need to understand what factors in the architecture contribute to overall system performance and the relative importance of these factors Effects of ISA on performance 2 How will hardware change affect performance CS2504, Spring'2007 ©Dimitris Nikolopoulos Airplane Performance Analogy Airplane Passengers Range Speed Boeing 777 375 4630 610 Boeing 747 470 4150 610 Concorde 132 4000 1250 Douglas DC-8-50 146 8720 544 Fighter Jet 4 2000 1500 What metric do we use? Concorde is 2.05 times faster than the 747 747 has 1.74 times higher throughput What about cost? And the winner is: It Depends! 3 CS2504, Spring'2007 ©Dimitris Nikolopoulos Throughput vs. Response Time Response Time: Execution time (e.g. seconds or clock ticks) How long does the program take to execute? How long do I have to wait for a result? Throughput: Rate of completion (e.g. results per second/tick) What is the average execution time of the program? Measure of total work done Upgrading to a newer processor will improve: response time Adding processors to the system will improve: throughput 4 CS2504, Spring'2007 ©Dimitris Nikolopoulos Example: Throughput vs. Response Time Suppose we know that an application that uses both a desktop client and a remote server is limited by network performance. -

CUDA 11 and A100 - WHAT’S NEW? Markus Hrywniak, 23Rd June 2020 TOPICS for TODAY

CUDA 11 AND A100 - WHAT’S NEW? Markus Hrywniak, 23rd June 2020 TOPICS FOR TODAY Ampere architecture – A100, powering DGX–A100, HGX-A100... and soon, FZ Jülich‘s JUWELS Booster New CUDA 11 Toolkit release Overview of features Talk next week: Third generation Tensor Cores GTC talks go into much more details. See references! 2 HGX-A100 4-GPU HGX-A100 8-GPU • 4 A100 with NVLINK • 8 A100 with NVSwitch 3 HIERARCHY OF SCALES Multi-System Rack Multi-GPU System Multi-SM GPU Multi-Core SM Unlimited Scale 8 GPUs 108 Multiprocessors 2048 threads 4 AMDAHL’S LAW serial section parallel section serial section Amdahl’s Law parallel section Shortest possible runtime is sum of serial section times Time saved serial section Some Parallelism Increased Parallelism Infinite Parallelism Program time = Parallel sections take less time Parallel sections take no time sum(serial times + parallel times) Serial sections take same time Serial sections take same time 5 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY serial section parallel section serial section Split up serial & parallel components parallel section serial section Some Parallelism Task Parallelism Infinite Parallelism Program time = Parallel sections overlap with serial sections Parallel sections take no time sum(serial times + parallel times) Serial sections take same time 6 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY CUDA Concurrency Mechanisms At Every Scope CUDA Kernel Threads, Warps, Blocks, Barriers Application CUDA Streams, CUDA Graphs Node Multi-Process Service, GPU-Direct System NCCL, CUDA-Aware MPI, NVSHMEM 7 OVERCOMING AMDAHL: ASYNCHRONY & LATENCY Execution Overheads Non-productive latencies (waste) Operation Latency Network latencies Memory read/write File I/O .. -

Analysis of Body Bias Control Using Overhead Conditions for Real Time Systems: a Practical Approach∗

IEICE TRANS. INF. & SYST., VOL.E101–D, NO.4 APRIL 2018 1116 PAPER Analysis of Body Bias Control Using Overhead Conditions for Real Time Systems: A Practical Approach∗ Carlos Cesar CORTES TORRES†a), Nonmember, Hayate OKUHARA†, Student Member, Nobuyuki YAMASAKI†, Member, and Hideharu AMANO†, Fellow SUMMARY In the past decade, real-time systems (RTSs), which must in RTSs. These techniques can improve energy efficiency; maintain time constraints to avoid catastrophic consequences, have been however, they often require a large amount of power since widely introduced into various embedded systems and Internet of Things they must control the supply voltages of the systems. (IoTs). The RTSs are required to be energy efficient as they are used in embedded devices in which battery life is important. In this study, we in- Body bias (BB) control is another solution that can im- vestigated the RTS energy efficiency by analyzing the ability of body bias prove RTS energy efficiency as it can manage the tradeoff (BB) in providing a satisfying tradeoff between performance and energy. between power leakage and performance without affecting We propose a practical and realistic model that includes the BB energy and the power supply [4], [5].Itseffect is further endorsed when timing overhead in addition to idle region analysis. This study was con- ducted using accurate parameters extracted from a real chip using silicon systems are enabled with silicon on thin box (SOTB) tech- on thin box (SOTB) technology. By using the BB control based on the nology [6], which is a novel and advanced fully depleted sili- proposed model, about 34% energy reduction was achieved. -

A Performance Analysis Tool for Intel SGX Enclaves

sgx-perf: A Performance Analysis Tool for Intel SGX Enclaves Nico Weichbrodt Pierre-Louis Aublin Rüdiger Kapitza IBR, TU Braunschweig LSDS, Imperial College London IBR, TU Braunschweig Germany United Kingdom Germany [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT the provider or need to refrain from offloading their workloads Novel trusted execution technologies such as Intel’s Software Guard to the cloud. With the advent of Intel’s Software Guard Exten- Extensions (SGX) are considered a cure to many security risks in sions (SGX)[14, 28], the situation is about to change as this novel clouds. This is achieved by offering trusted execution contexts, so trusted execution technology enables confidentiality and integrity called enclaves, that enable confidentiality and integrity protection protection of code and data – even from privileged software and of code and data even from privileged software and physical attacks. physical attacks. Accordingly, researchers from academia and in- To utilise this new abstraction, Intel offers a dedicated Software dustry alike recently published research works in rapid succession Development Kit (SDK). While it is already used to build numerous to secure applications in clouds [2, 5, 33], enable secure network- applications, understanding the performance implications of SGX ing [9, 11, 34, 39] and fortify local applications [22, 23, 35]. and the offered programming support is still in its infancy. This Core to all these works is the use of SGX provided enclaves, inevitably leads to time-consuming trial-and-error testing and poses which build small, isolated application compartments designed to the risk of poor performance.