CS2504: Computer Organization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

45-Year CPU Evolution: One Law and Two Equations

45-year CPU evolution: one law and two equations Daniel Etiemble LRI-CNRS University Paris Sud Orsay, France [email protected] Abstract— Moore’s law and two equations allow to explain the a) IC is the instruction count. main trends of CPU evolution since MOS technologies have been b) CPI is the clock cycles per instruction and IPC = 1/CPI is the used to implement microprocessors. Instruction count per clock cycle. c) Tc is the clock cycle time and F=1/Tc is the clock frequency. Keywords—Moore’s law, execution time, CM0S power dissipation. The Power dissipation of CMOS circuits is the second I. INTRODUCTION equation (2). CMOS power dissipation is decomposed into static and dynamic powers. For dynamic power, Vdd is the power A new era started when MOS technologies were used to supply, F is the clock frequency, ΣCi is the sum of gate and build microprocessors. After pMOS (Intel 4004 in 1971) and interconnection capacitances and α is the average percentage of nMOS (Intel 8080 in 1974), CMOS became quickly the leading switching capacitances: α is the activity factor of the overall technology, used by Intel since 1985 with 80386 CPU. circuit MOS technologies obey an empirical law, stated in 1965 and 2 Pd = Pdstatic + α x ΣCi x Vdd x F (2) known as Moore’s law: the number of transistors integrated on a chip doubles every N months. Fig. 1 presents the evolution for II. CONSEQUENCES OF MOORE LAW DRAM memories, processors (MPU) and three types of read- only memories [1]. The growth rate decreases with years, from A. -

Cuda C Best Practices Guide

CUDA C BEST PRACTICES GUIDE DG-05603-001_v9.0 | June 2018 Design Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface............................................................................................................ vii What Is This Document?..................................................................................... vii Who Should Read This Guide?...............................................................................vii Assess, Parallelize, Optimize, Deploy.....................................................................viii Assess........................................................................................................ viii Parallelize.................................................................................................... ix Optimize...................................................................................................... ix Deploy.........................................................................................................ix Recommendations and Best Practices.......................................................................x Chapter 1. Assessing Your Application.......................................................................1 Chapter 2. Heterogeneous Computing.......................................................................2 2.1. Differences between Host and Device................................................................ 2 2.2. What Runs on a CUDA-Enabled Device?...............................................................3 Chapter 3. Application Profiling............................................................................. -

Multi-Cycle Datapathoperation

Book's Definition of Performance • For some program running on machine X, PerformanceX = 1 / Execution timeX • "X is n times faster than Y" PerformanceX / PerformanceY = n • Problem: – machine A runs a program in 20 seconds – machine B runs the same program in 25 seconds 1 Example • Our favorite program runs in 10 seconds on computer A, which hasa 400 Mhz. clock. We are trying to help a computer designer build a new machine B, that will run this program in 6 seconds. The designer can use new (or perhaps more expensive) technology to substantially increase the clock rate, but has informed us that this increase will affect the rest of the CPU design, causing machine B to require 1.2 times as many clockcycles as machine A for the same program. What clock rate should we tellthe designer to target?" • Don't Panic, can easily work this out from basic principles 2 Now that we understand cycles • A given program will require – some number of instructions (machine instructions) – some number of cycles – some number of seconds • We have a vocabulary that relates these quantities: – cycle time (seconds per cycle) – clock rate (cycles per second) – CPI (cycles per instruction) a floating point intensive application might have a higher CPI – MIPS (millions of instructions per second) this would be higher for a program using simple instructions 3 Performance • Performance is determined by execution time • Do any of the other variables equal performance? – # of cycles to execute program? – # of instructions in program? – # of cycles per second? – average # of cycles per instruction? – average # of instructions per second? • Common pitfall: thinking one of the variables is indicative of performance when it really isn’t. -

Analysis of Body Bias Control Using Overhead Conditions for Real Time Systems: a Practical Approach∗

IEICE TRANS. INF. & SYST., VOL.E101–D, NO.4 APRIL 2018 1116 PAPER Analysis of Body Bias Control Using Overhead Conditions for Real Time Systems: A Practical Approach∗ Carlos Cesar CORTES TORRES†a), Nonmember, Hayate OKUHARA†, Student Member, Nobuyuki YAMASAKI†, Member, and Hideharu AMANO†, Fellow SUMMARY In the past decade, real-time systems (RTSs), which must in RTSs. These techniques can improve energy efficiency; maintain time constraints to avoid catastrophic consequences, have been however, they often require a large amount of power since widely introduced into various embedded systems and Internet of Things they must control the supply voltages of the systems. (IoTs). The RTSs are required to be energy efficient as they are used in embedded devices in which battery life is important. In this study, we in- Body bias (BB) control is another solution that can im- vestigated the RTS energy efficiency by analyzing the ability of body bias prove RTS energy efficiency as it can manage the tradeoff (BB) in providing a satisfying tradeoff between performance and energy. between power leakage and performance without affecting We propose a practical and realistic model that includes the BB energy and the power supply [4], [5].Itseffect is further endorsed when timing overhead in addition to idle region analysis. This study was con- ducted using accurate parameters extracted from a real chip using silicon systems are enabled with silicon on thin box (SOTB) tech- on thin box (SOTB) technology. By using the BB control based on the nology [6], which is a novel and advanced fully depleted sili- proposed model, about 34% energy reduction was achieved. -

A Performance Analysis Tool for Intel SGX Enclaves

sgx-perf: A Performance Analysis Tool for Intel SGX Enclaves Nico Weichbrodt Pierre-Louis Aublin Rüdiger Kapitza IBR, TU Braunschweig LSDS, Imperial College London IBR, TU Braunschweig Germany United Kingdom Germany [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT the provider or need to refrain from offloading their workloads Novel trusted execution technologies such as Intel’s Software Guard to the cloud. With the advent of Intel’s Software Guard Exten- Extensions (SGX) are considered a cure to many security risks in sions (SGX)[14, 28], the situation is about to change as this novel clouds. This is achieved by offering trusted execution contexts, so trusted execution technology enables confidentiality and integrity called enclaves, that enable confidentiality and integrity protection protection of code and data – even from privileged software and of code and data even from privileged software and physical attacks. physical attacks. Accordingly, researchers from academia and in- To utilise this new abstraction, Intel offers a dedicated Software dustry alike recently published research works in rapid succession Development Kit (SDK). While it is already used to build numerous to secure applications in clouds [2, 5, 33], enable secure network- applications, understanding the performance implications of SGX ing [9, 11, 34, 39] and fortify local applications [22, 23, 35]. and the offered programming support is still in its infancy. This Core to all these works is the use of SGX provided enclaves, inevitably leads to time-consuming trial-and-error testing and poses which build small, isolated application compartments designed to the risk of poor performance. -

ESC-470: ARM 9 Instruction Set Architecture with Performance

ARM 9 Instruction Set Architecture Introduction with Performance Perspective Joe-Ming Cheng, Ph.D. ARM-family processors are positioned among the leaders in key embedded applications. Many presentations and short lectures have already addressed the ARM’s applications and capabilities. In this introduction, we intend to discuss the ARM’s instruction set uniqueness from the performance prospective. This introduction is also trying to follow the approaches established by two outstanding textbooks of David Patterson and John Hennessey [PetHen00] [HenPet02]. 1.0 ARM Instruction Set Architecture Processor instruction set architecture (ISA) choices have evolved from accumulator, stack, register-to- memory, to register-register (load-store) organization. ARM 9 ISA is a load-store machine. ARM 9 ISA takes advantage of its smaller set of registers (16 vs. many 32-register processors) to incorporate more direct controls and achieve high encoding density. ARM’s load or store multiple register instruction, for example , allows enlisting of all possible registers and conditional execution in one instruction. The Thumb mode instruction set is another exa mple of how ARM ISA facilitates higher encode density. Rather than compressing the code, Thumb -mode instructions are two 16-bit instructions packed in a 32-bit ARM-mode instruction space. The Thumb -mode instructions are a subset of ARM instructions. When executing in Thumb mode, a single 32-bit instruction fetch cycle effectively brings in two instructions. Thumb code reduces access bandwidth, code size, and improves instruction cache hit rate. Another way ARM achieves cycle time reduction is by using Harvard architecture. The architecture facilitates independent data and instruction buses. -

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 L/780

A Characterization of Processor Performance in the VAX-1 l/780 Joel S. Emer Douglas W. Clark Digital Equipment Corp. Digital Equipment Corp. 77 Reed Road 295 Foster Street Hudson, MA 01749 Littleton, MA 01460 ABSTRACT effect of many architectural and implementation features. This paper reports the results of a study of VAX- llR80 processor performance using a novel hardware Prior related work includes studies of opcode monitoring technique. A micro-PC histogram frequency and other features of instruction- monitor was buiit for these measurements. It kee s a processing [lo. 11,15,161; some studies report timing count of the number of microcode cycles execute z( at Information as well [l, 4,121. each microcode location. Measurement ex eriments were performed on live timesharing wor i loads as After describing our methods and workloads in well as on synthetic workloads of several types. The Section 2, we will re ort the frequencies of various histogram counts allow the calculation of the processor events in 5 ections 3 and 4. Section 5 frequency of various architectural events, such as the resents the complete, detailed timing results, and frequency of different types of opcodes and operand !!Iection 6 concludes the paper. specifiers, as well as the frequency of some im lementation-s ecific events, such as translation bu h er misses. ?phe measurement technique also yields the amount of processing time spent, in various 2. DEFINITIONS AND METHODS activities, such as ordinary microcode computation, memory management, and processor stalls of 2.1 VAX-l l/780 Structure different kinds. This paper reports in detail the amount of time the “average’ VAX instruction The llf780 processor is composed of two major spends in these activities. -

Autotuning GPU Kernels Via Static and Predictive Analysis

Autotuning GPU Kernels via Static and Predictive Analysis Robert V. Lim, Boyana Norris, and Allen D. Malony Computer and Information Science University of Oregon Eugene, OR, USA froblim1, norris, [email protected] Abstract—Optimizing the performance of GPU kernels is branches occur, threads that do not satisfy branch conditions challenging for both human programmers and code generators. are masked out. If the kernel programmer is unaware of the For example, CUDA programmers must set thread and block code structure or the hardware underneath, it will be difficult parameters for a kernel, but might not have the intuition to make a good choice. Similarly, compilers can generate working for them to make an effective decision about thread and block code, but may miss tuning opportunities by not targeting GPU parameters. models or performing code transformations. Although empirical CUDA developers face two main challenges, which we autotuning addresses some of these challenges, it requires exten- aim to alleviate with the approach described in this paper. sive experimentation and search for optimal code variants. This First, developers must correctly select runtime parameters research presents an approach for tuning CUDA kernels based on static analysis that considers fine-grained code structure and as discussed above. A developer or user may not have the the specific GPU architecture features. Notably, our approach expertise to decide on parameter settings that will deliver does not require any program runs in order to discover near- high performance. In this case, one can seek guidance from optimal parameter settings. We demonstrate the applicability an optimization advisor. The advisor could consult a perfor- of our approach in enabling code autotuners such as Orio to mance model based on static analysis of the kernel properties, produce competitive code variants comparable with empirical- based methods, without the high cost of experiments. -

The Anatomy of the ARM Cortex-M0+ Processor

The Anatomy of the ARM Cortex-M0+ Processor Joseph Yiu Embedded Technology Specialist 1 What is the Cortex-M0+ Processor? . 2009 – ARM® Cortex™-M0 processor released . Low gate count . High performance . Easy to use . Debug features . 2012 – Cortex-M0+ processor released . Same instruction set . Supports all existing features of Cortex-M0 . New features . Higher energy efficiency . Ready for future applications 2 What’s new? . Even better power efficiency . Clean sheet design – 2 stage pipeline . Better performance at the same frequency . Unprivileged execution level . 8 region Memory Protection Unit (MPU) . Faster I/O accesses . Vector table relocation . Low cost trace solution available . Various silicon integration features (e.g.16-bit flash support) 3 Why a New Design? Energy is the Key . Embedded products need even longer battery life . Need to have lower active power . But not compromise on performance . Low power control applications . Need to have faster I/O capability . But not higher operating frequency . Smarter designs . Need more sophisticated features . But not bigger silicon 4 Overview of the Cortex-M0+ Processor . Processor . ARMv6-M architecture . Easy to use, C friendly . Cortex-M series compatibility . Nested Vectored Interrupt Controller (NVIC) . Flexible interrupt handling . WIC support . Memory Protection Unit (MPU) . Debug from just 2 pins 5 Compact Instruction Set . Only 56 Instructions . 100% compatible with existing Cortex-M0 processor . Mostly 16-bit instructions . All instructions operate on the 32-bit registers . Option for single cycle 32x32 Maximum reuse of multiply Upwardexisting compatibility tools to andthe ARM Cortexecosystem-M3/Cortex -M4 6 Interrupt Handling . Nested Vectored Interrupt Cortex-M0+ Controller (NVIC) NMI NVIC Core . -

Microarchitecture-Level Power-Performance Simulators: Modeling, Validation, and Impact on Design

Microarchitecture-Level Power-Performance Simulators: Modeling, Validation, and Impact on Design Zhigang Hu, David Brooks, Victor Zyuban, Pradip Bose IBM Research Harvard University Tutorial Outline 8:00-8:15 Introduction and Motivation Basics of Performance Modeling - Turandot performance simulation infrastructure Architectural Power Modeling - PowerTimer extensions to Turandot - Power-Performance Efficiency Metrics Case Studies and Examples - Optimal Power-Performance Pipeline Depth Validation and Calibration Efforts Future challenges and Discussion Bibliography Power Dissipation Trends 1000 ) 2 Intel Data SIA Projection Nuclear Reactor 100 Pentium III Hot Plate Pentium II 10 Pentium Pro Pentium Power Density (W/cm Density Power 486 1 386 1980 1990 2000 2010 The Battery Gap Diverging Gap Between Actual Battery Capacities and Energy Needs 10kbps 64kbps 384kbps 2Mbps 5000 Interactive Mobile video- 4000 Conferencing, Collaboration Video email, 3000 Voice recognition, Battery Downlink Mobile commerce capacity (mAh) dominated Fuel Cells 2000 Web browser, Energy PIM, SMS, MMS, Video clips requirement Voice (mAh) Energy (mAh) 1000 Lithium Source: Lithium Ion Polymer Anand 0 Raghunathan, NEC Labs 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 Power Issues Capacitive (Dynamic) Power Static (Leakage) Power Vdd VIN VOUT Vin Vout ISub CL IGate CL Temperature Di/Dt (Vdd/Gnd Bounce) 20 cycles Voltage (V) (A) Current Minimum Voltage Application Areas for Power-Aware Computing Temperature/di-dt-Constrained Energy-Constrained Computing Why architecture/system -

Assembly Language Programming (Part 1) 2 7

COURSE OUTLINE SECTION 1 1. Introduction to Programming languages Machine Language Low-Level Language High-Level Language 2. Data Representation & Numbering Systems Binary Numbering Systems Octal Numbering Systems Decimal Numbering Systems Hexadecimal Numbering Systems 3. Types of encoding American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) Binary Coded Decimal (BCD) Extended Binary Coded Decimal Interchange Code (EBCDIC) 4. Mode of data representation Integer Representation Floating Point Representation 5. Computer instruction set Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) Complex Instruction Set Computer (CISC) SECTION TWO 6. Registers General Purpose Registers Segment Registers Special Purpose Registers ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING (PART 1) 2 7. 80x86 instruction sets and Modes of addressing. Addressing modes with Register operands Addressing modes with constants Addressing modes with memory operands Addressing mode with stack memory 8. Instruction Sets The 80x86 instruction sets The control transfer instruction The standard input routines The standard output routines Macros 9. Assembly Language Programs An overview of Assembly Language program The linker Examples of common Assemblers A simple Hello World Program using FASM A simple Hello World Program using NASMS 10. Job Control Language Introduction Basic syntax of JCL statements ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING (PART 1) 3 Types of JCL statements The JOB statement The EXEC statement The DD statement ASSEMBLY LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING (PART 1) 4 CHAPTER ONE 1.0 INTRODUCTION TO PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES Programmers write instructions in various programming languages, some directly understandable by computers and others requiring intermediate translation steps. Hundreds of computer languages are in use today. These can be divided into three general types: a. Machine Language b. Low Level Language c. -

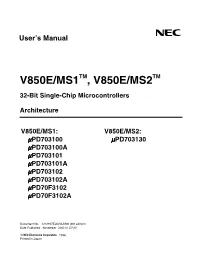

V850e/Ms1 , V850e/Ms2

User’s Manual V850E/MS1TM, V850E/MS2TM 32-Bit Single-Chip Microcontrollers Architecture V850E/MS1: V850E/MS2: µPD703100 µPD703130 µPD703100A µPD703101 µPD703101A µPD703102 µPD703102A µPD70F3102 µPD70F3102A Document No. U12197EJ6V0UM00 (6th edition) Date Published November 2002 N CP(K) 1996 Printed in Japan [MEMO] 2 User’s Manual U12197EJ6V0UM NOTES FOR CMOS DEVICES 1 PRECAUTION AGAINST ESD FOR SEMICONDUCTORS Note: Strong electric field, when exposed to a MOS device, can cause destruction of the gate oxide and ultimately degrade the device operation. Steps must be taken to stop generation of static electricity as much as possible, and quickly dissipate it once, when it has occurred. Environmental control must be adequate. When it is dry, humidifier should be used. It is recommended to avoid using insulators that easily build static electricity. Semiconductor devices must be stored and transported in an anti-static container, static shielding bag or conductive material. All test and measurement tools including work bench and floor should be grounded. The operator should be grounded using wrist strap. Semiconductor devices must not be touched with bare hands. Similar precautions need to be taken for PW boards with semiconductor devices on it. 2 HANDLING OF UNUSED INPUT PINS FOR CMOS Note: No connection for CMOS device inputs can be cause of malfunction. If no connection is provided to the input pins, it is possible that an internal input level may be generated due to noise, etc., hence causing malfunction. CMOS devices behave differently than Bipolar or NMOS devices. Input levels of CMOS devices must be fixed high or low by using a pull-up or pull-down circuitry.