A Comparison of the Fairtax Base and Rate with Other Tax Reform

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tearing out the Income Tax by the (Grass)Roots

FLORIDA TAX REVIEW Volume 15 2014 Number 8 TEARING OUT THE INCOME TAX BY THE (GRASS)ROOTS by Lawrence Zelenak* Rich People’s Movements: Grassroots Campaigns to Untax the One Percent. By Isaac William Martin New York: Oxford University Press. 2013. I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 649 II. A CENTURY OF RICH PEOPLE’S ANTI-TAX MOVEMENTS ......... 651 III. EXPLAINING THE SUPPORT OF THE NON-RICH .......................... 656 IV. BUT WHAT ABOUT THE FLAT TAX AND THE FAIRTAX? ............ 661 V. THE RHETORIC OF RICH PEOPLE’S ANTI-TAX MOVEMENTS: PARANOID AND NON-PARANOID STYLES .................................... 665 VI. CONCLUSION ................................................................................. 672 I. INTRODUCTION Why do rich people seeking reductions in their tax burdens, who have the ability to influence Congress directly through lobbying and campaign contributions, sometimes resort to grassroots populist methods? And why do non-rich people sometimes join the rich in their anti-tax movements? These are the puzzles Isaac William Martin sets out to solve in Rich People’s Movements.1 Martin’s historical research—much of it based on original sources to which scholars have previously paid little or no attention—reveals that, far from being a recent innovation, populist-style movements against progressive federal taxation go back nearly a century, to the 1920s. Although Martin identifies various anti-tax movements throughout the past century, he strikingly concludes that there has been “substantial continuity from one campaign to the next, so that, in some * Pamela B. Gann Professor of Law, Duke Law School. 1. ISAAC WILLIAM MARTIN, RICH PEOPLE’S MOVEMENTS: GRASSROOTS CAMPAIGNS TO UNTAX THE ONE PERCENT (2013) [hereinafter MARTIN, RICH PEOPLE’S MOVEMENTS]. -

Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System

TAX POLICY CENTER BRIEFING BOOK Key Elements of the U.S. Tax System TAXES AND THE FAMILY What are marriage penalties and bonuses? XXXX Q. What are marriage penalties and bonuses? A. A couple incurs a marriage penalty if the two pay more income tax filing as a married couple than they would pay if they were single and filed as individuals. Conversely, a couple receives a marriage bonus if they pay less tax filing as a couple than they would if they were single. CAUSES OF MARRIAGE BONUSES AND PENALTIES Marriage penalties and bonuses occur because income taxes apply to a couple, not to individual spouses. Under a progressive income tax, a couple’s income can be taxed more or less than that of two single individuals. A couple is not obliged to file a joint tax return, but their alternative—filing separate returns as a married couple—almost always results in higher tax liability. Married couples with children are more likely to incur marriage penalties than couples without children because one or both spouses could use the head of household filing status if they were able to file as singles. And tax provisions that phase in or out with income also produce marriage penalties or bonuses. Marriage penalties are more common when spouses have similar incomes. Marriage bonuses are more common when spouses have disparate incomes. Overall, couples receiving bonuses greatly outnumber those incurring penalties. MARRIAGE PENALTIES Couples in which spouses have similar incomes are more likely to incur marriage penalties than couples in which one spouse earns most of the income, because combining incomes in joint filing can push both spouses into higher tax brackets. -

A PORTRAIT of TRADE in VALUE-ADDED OVER FOUR DECADES Robert C

A PORTRAIT OF TRADE IN VALUE-ADDED OVER FOUR DECADES Robert C. Johnson and Guillermo Noguera* Abstract—We combine data on trade, production, and input use to document We show that changes in trade frictions, particularly fric- changes in the value-added content of trade between 1970 and 2009. The ratio of value-added to gross exports fell by roughly 10 percentage points tions for manufactured inputs, play a key role in explaining worldwide. The ratio declined 20 percentage points in manufacturing, but all five stylized facts. rose in nonmanufacturing sectors. Declines also differ across countries and To track value-added trade over time, we combine time trade partners: they are larger for fast-growing countries, for nearby trade partners, and among partners that adopt regional trade agreements. Using series data on trade, production, and input use to con- a multisector structural gravity model with input-output linkages, we show struct an annual sequence of global bilateral input-output that changes in trade frictions play a dominant role in explaining all these tables covering 42 countries back to 1970. These synthetic facts. tables track shipments of final and intermediate goods within and between countries. Using this framework, we compute I. Introduction value-added exports: the amount of value added from a given source country that is consumed in each destination ECENT decades have seen the emergence of global (i.e., embodied in final goods absorbed in that destination) supply chains. Echoing Feenstra (1998), rising trade R (Johnson & Noguera, 2012a). Value-added exports mea- integration has coincided with the simultaneous disintegra- sure international transactions in a manner consistent with tion of production across borders. -

MAGI 2.0 Part 2: Income Counting

MAGI 2.0: Building MAGI Knowledge Part 2: Income Counting Last Updated: December 11, 2020 Introduction Setting the Stage 3 . In 2020, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) updated a training manual originally developed in 2013 to help states and eligibility workers understand and apply Modified Adjust Gross Income (MAGI)-based rules for Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The manual is available at https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/mac- learning-collaboratives/downloads/household-composition-and-income-training.zip. This MAGI 2.0: Building MAGI Knowledge slide deck serves as a companion to the Household and MAGI Income Training Manual, providing more details on how to apply the MAGI-based income counting rules. The issues and scenarios reviewed in this slide deck were developed in response to frequently asked technical assistance questions raised by states and revised based on updated guidance that was released. Two-Part Resource 4 Determining Household Composition Calculating Household Income Focus of This Resource Determining Household Income 5 Key Questions When Determining Household Income: Whose income is counted? What income is counted? Over what period is income counted? Whose Income Is Counted? 6 Generally, to determine MAGI-based household income: . Count the MAGI-based income of adults in the household. Do not count the MAGI-based income of children in the household. Let’s discuss this rule… Income Counting Rules 7 Regulatory Requirements . Household income includes the Relevant Regulatory Language: MAGI-based income of all 42 CFR 435.603(d)(1) individuals in the MAGI-based Household income is the sum of the MAGI-based income…of every household, with specific individual included in the individual’s household [unless an exception exceptions. -

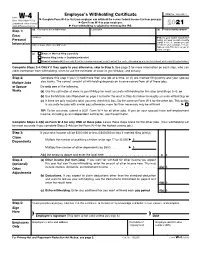

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

ITEMIZING on STATE and FEDERAL TAX INCOME RETURNS: IT’S (NOW MORE) COMPLICATED David Weiner December 2, 2020

ITEMIZING ON STATE AND FEDERAL TAX INCOME RETURNS: IT’S (NOW MORE) COMPLICATED David Weiner December 2, 2020 A taxpayer’s decision to itemize deductions or to claim the standard deduction on their income tax return is often framed as a simple calculation: Claim the greater of the two so as to minimize tax liability. But in states that require taxpayers to use the same status on their state income tax return as on their federal return, this general rule can produce conflicting results if taxpayers examine liability separately on their federal and state returns. Itemized deductions might be greater than the standard deduction on a state income tax return, but the reverse could be true on a federal return. Recent federal law changes have further complicated the choice. When the federal standard deduction was nearly doubled beginning in 2018, many more taxpayers found a conflict between the best itemization scenario on federal and state income tax returns. Those taxpayers must now calculate their federal and state income taxes under both scenarios if they want to minimize their combined state and federal income tax liability. Many taxpayers in states that link federal and state itemization choices are affected. In Maryland, for example, more than 200,000 taxpayers could benefit by itemizing on their federal returns when that may not be the obvious choice. In this brief, I examine the links between federal and state itemization decisions and explore the implications of relaxing state rules requiring that state itemization choices match federal ones. elatively few federal taxpayers itemize deductions on their income tax returns under current law, and those who do tend to have very high incomes. -

Itep Guide to Fair State and Local Taxes: About Iii

THE GUIDE TO Fair State and Local Taxes 2011 Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy 1616 P Street, NW, Suite 201, Washington, DC 20036 | 202-299-1066 | www.itepnet.org | [email protected] THE ITEP GUIDE TO FAIR STATE AND LOCAL TAXES: ABOUT III About the Guide The ITEP Guide to Fair State and Local Taxes is designed to provide a basic overview of the most important issues in state and local tax policy, in simple and straightforward language. The Guide is also available to read or download on ITEP’s website at www.itepnet.org. The web version of the Guide includes a series of appendices for each chapter with regularly updated state-by-state data on selected state and local tax policies. Additionally, ITEP has published a series of policy briefs that provide supplementary information to the topics discussed in the Guide. These briefs are also available on ITEP’s website. The Guide is the result of the diligent work of many ITEP staffers. Those primarily responsible for the guide are Carl Davis, Kelly Davis, Matthew Gardner, Jeff McLynch, and Meg Wiehe. The Guide also benefitted from the valuable feedback of researchers and advocates around the nation. Special thanks to Michael Mazerov at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. About ITEP Founded in 1980, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) is a non-profit, non-partisan research organization, based in Washington, DC, that focuses on federal and state tax policy. ITEP’s mission is to inform policymakers and the public of the effects of current and proposed tax policies on tax fairness, government budgets, and sound economic policy. -

Chapter 2: What's Fair About Taxes?

Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_35 rev0 page 35 2. What’s Fair about Taxes? economists and politicians of all persuasions agree on three points. One, the federal income tax is not sim- ple. Two, the federal income tax is too costly. Three, the federal income tax is not fair. However, economists and politicians do not agree on a fourth point: What does fair mean when it comes to taxes? This disagree- ment explains, in large measure, why it so difficult to find a replacement for the federal income tax that meets the other goals of simplicity and low cost. In recent years, the issue of fairness has come to overwhelm the other two standards used to evaluate tax systems: cost (efficiency) and simplicity. Recall the 1992 presidential campaign. Candidate Bill Clinton preached that those who “benefited unfairly” in the 1980s [the Tax Reform Act of 1986 reduced the top tax rate on upper-income taxpayers from 50 percent to 28 percent] should pay their “fair share” in the 1990s. What did he mean by such terms as “benefited unfairly” and should pay their “fair share?” Were the 1985 tax rates fair before they were reduced in 1986? Were the Carter 1980 tax rates even fairer before they were reduced by President Reagan in 1981? Were the Eisenhower tax rates fairer still before President Kennedy initiated their reduction? Were the original rates in the first 1913 federal income tax unfair? Were the high rates that prevailed during World Wars I and II fair? Were Andrew Mellon’s tax Hoover Classics : Flat Tax hcflat ch2 Mp_36 rev0 page 36 36 The Flat Tax rate cuts unfair? Are the higher tax rates President Clin- ton signed into law in 1993 the hallmark of a fair tax system, or do rates have to rise to the Carter or Eisen- hower levels to be fair? No aspect of federal income tax policy has been more controversial, or caused more misery, than alle- gations that some individuals and income groups don’t pay their fair share. -

Your Federal Tax Burden Under Current Law and the Fairtax by Ross Korves

A FairTaxSM White Paper Your federal tax burden under current law and the FairTax by Ross Korves As farmers and ranchers prepare 2006 federal income tax returns or provide income and expense information to accountants and other tax professionals, a logical question is how would the tax burden change under the FairTax? The FairTax would eliminate all individual and corporate income taxes, all payroll taxes and self-employment taxes for Social Security and Medicare, and the estate tax and replace them with a national retail sales tax on final consumption of goods and services. Payroll and self-employment taxes The starting point in calculating the current tax burden is payroll taxes and self-employment taxes. Most people pay more money in payroll and self-employment taxes than they do in income taxes because there are no standard deductions or personal exemptions that apply to payroll and self-employment taxes. You pay tax on the first dollar earned. While employees see only 7.65 percent taken out of their paychecks, the reality is that the entire 15.3 percent payroll tax is part of the cost of having an employee and is a factor in determining how much an employer can afford to pay in wages. Self-employed taxpayers pay both the employer and employee portions of the payroll tax on their earnings, and the entire 15.3 percent on 92.35 percent of their self-employed income (they do not pay on the 7.65 percent of wages that employees do not receive as income); however, they are allowed to deduct the employer share of payroll taxes against the income tax. -

Section 111.—Recovery of Tax Benefit Items 26 CFR 1.111-1

Section 111.—Recovery of Tax Benefit Items 26 CFR 1.111-1: Recovery of certain items previously deducted or credited. (Also: § 164; 1.164-1.) Rev. Rul. 2019-11 ISSUE If a taxpayer received a tax benefit from deducting state and local taxes under section 164 of the Internal Revenue Code in a prior taxable year, and the taxpayer recovers all or a portion of those taxes in the current taxable year, what portion of the recovery must the taxpayer include in gross income? FACTS In Situations 1 through 4 below, the taxpayers are unmarried individuals whose filing status is “single” and who itemized deductions on their federal income tax returns for 2018 in lieu of using their standard deduction of $12,000. The taxpayers did not pay or accrue the taxes in carrying on a trade or business or an activity described in section 212. For 2018, the taxpayers were not subject to alternative minimum tax under section 55 and were not entitled to any credit against income tax. The taxpayers use the cash receipts and disbursements method of accounting. Situation 1: Taxpayer A paid local real property taxes of $4,000 and state income taxes of $5,000 in 2018. A’s state and local tax deduction was not limited by section 164(b)(6) because it was below $10,000. Including other allowable itemized deductions, A claimed a total of $14,000 in itemized deductions on A’s 2018 federal income tax return. In 2019, A received a $1,500 state income tax refund due to A’s overpayment of state income taxes in 2018. -

2019 M1SA, Minnesota Itemized Deductions

*191161* 2019 Schedule M1SA, Minnesota Itemized Deductions Your First Name and Initial Last Name Your Social Security Number Medical and Dental Expenses 1 Medical and dental expenses (see instructions) . 1 2 Enter the amount from line 1 of Form M1 . If zero or less, enter 0 . 2 3 Multiply line 2 by 10% (.10). 3 4 Subtract line 3 from line 1. If line 3 is more than line 1, enter 0 . 4 Taxes You Paid 5 Real estate taxes (see instructions) . 5 6 Personal property taxes (see instructions) . 6 7 Add lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Enter the lesser of line 7 or $10,000 ($5,000 if married filing separate) 8 9 Other taxes. List the type and amount . 9 10 Add lines 8 and 9 . 10 Interest You Paid 11 Home mortgage interest and points on federal Form 1098 . 11 12 Home mortgage interest and points not reported to you on Form 1098 (see instructions) 12 13 Investment interest expense . 13 14 Add lines 11 through 13 . 14 Charitable Contributions 15 Charitable contributions by cash or check (see instructions) . 15 16 Charitable contributions by other than cash or check (see instructions) 16 17 Carryover of charitable contributions from a prior year . 17 18 Add lines 15 through 17 . 18 Casualty and Theft Losses 19 Casualty or theft loss (enclose Schedule M1CAT) . 19 Unreimbursed Employee Business Expenses 20 Unreimbursed employee expenses (enclose Schedule M1UE) . 20 21 Enter the amount from line 1 of Form M1 . If zero or less, enter 0 . 21 22 Multiply line 21 by 2% (.02) . -

Traditional IRA SEP IRA Roth IRA

Traditional IRA SEP IRA Roth IRA Disclosure Statement & Custodial Account Agreement Table of Contents Page in Document PART I ‐ COMBINED DISCLOSURE STATEMENT AND CUSTODIAL ACCOUNT AGREEMENT ................................................................... 1 TRADITIONAL INDIVIDUAL RETIREMENT ACCOUNT DISCLOSURE ............................................................................................... 5 ROTH INDIVIDUAL RETIREMENT ACCOUNT DISCLOSURE ........................................................................................................... 9 TRADITIONAL IRA CUSTODIAL ACCOUNT AGREEMENT ............................................................................................................ 13 ROTH IRA CUSTODIAL ACCOUNT AGREEMENT ........................................................................................................................ 18 PART II ‐ TRADITIONAL AND ROTH IRA APPLICATION AND ADOPTION AGREEMENT INSTRUCTIONS ................................................. 23 PART III ‐ TRADITIONAL AND ROTH IRA APPLICATION AND ADOPTION AGREEMENT ....................................................................... 25 CERTIFICATION OF ROLLOVER ASSETS .................................................................................................................................... 33 TRANSFER OF ASSETS/DIRECT ROLLOVER FORM ..................................................................................................................... 35 PART IV – PRIVACY POLICY ...........................................................................................................................................................